Story

The San Isabel: Colorado’s Historic Mountain Playground

San Isabel National Forest in southern Colorado has a long history as a destination for folks seeking a getaway in the great outdoors – but that wasn’t originally the plan.

Editor’s Note: This article is published in partnership with Frontier Pathways, and came out originally in 2006. A list of sites of interest for those driving through San Isabel National Forest was originally included in that pamphlet, and is available for download here.

Some of the terminology is outdated and does not align with current preferred language. Click here to learn more about our anti-racist grounding virtues online.

You are about to start an exciting trip. You will discover, visit and learn about some of southern Colorado’s earliest and most significant recreational roads; the site of an important 1933 Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) camp; municipal mountain parks, resorts, and more. Your tour showcases the recreational development of the San Isabel region in the first part of the 20th century, much of which remains today to be enjoyed and appreciated. The recreational heritage of the San Isabel exemplifies the history of mountain recreational development for the use of people all over America and is part of the great “outdoors movement” that changed the lives of millions of working-class Americans forever.

In addition to the rich recreational history, you will see beautiful scenery and a rich diversity of plant, animal and geological marvels.

Early History

The terrain and animals greatly influenced the lives of the first people in Colorado. Paleo-Indians took refuge in sheltered valleys. They camped near streams and springs. They traveled on trails from plains to mountain valleys to hunt game animals and harvest wild plants. Evidence of these early Paleo-Indians has been found near Wetmore and the Bigelow Divide near Highway 96. The Ute lived in the high country of Colorado, including the Wet Mountains and the Wet Mountain Valley. Extended family groups typically spent summers in the mountains gathering food and hunting. Winters were spent in the lower-elevation basins.

The paths created by the Ute became some of the first trails in the Colorado mountains, including your route through the Hardscrabble Canyon on Highway 96, portions of Highway 12 west of Trinidad and Sulphur Springs near La Veta on County Road 421.

In the 1800s, the lives of the first Coloradoans would change greatly. Starting in 1858, the lure of gold brought many newcomers to Colorado. As the goldseekers took over the Native Americans’ territory, conflicts ensued. Many treaties were made, and then broken. The American Indians, including the Ute, were forced onto reservations.

The Spanish also traversed this same territory in Southern Colorado. Juan de Ulibarri (1706) traveled through the Pueblo area toward El Cuartelejo, a site thought to be in what is now southwestern Kansas. Further Spanish expeditions of exploration and conquest produced maps and descriptions of the territory. Juan Bautista de Anza’s 1779 military expedition traveled through southwestern Colorado in pursuit of the Comanche leader Cuerno Verde. By around 1800, New Spain considered the Arkansas River, which flows through Pueblo, its northern border. The Spanish influence is still apparent today in the name of places. The Sangre de Cristo, the mountain range that borders the San Isabel National Forest, is Spanish for the “blood of Christ.”

Many mountain men trapped beaver in the San Isabel area. They were men lured by the adventure of exploring uncharted wilderness. They made their living by supplying animal hides to traders. Little is known of these earliest adventurers in the San Isabel area before the 1800s, although it is likely that French trappers were here as early as the mid-1700s. In the early 1800s until the mid-1840s, beaver pelts were in high demand. The soft underfur was made into felt for stylish top hats. In the 1840s, silk top hats became more fashionable, and the bottom dropped out of the beaver market.

Many of the trappers began hunting bison or scouting for western expeditions. Some became traders. Still others settled down to become farmers. Some became famous for their exploits, even as far away as Europe. Mountain men like Christopher “Kit” Carson, Bill “Big Foot” Williams, and traders like the Bent and St. Vrain brothers and George Simpson worked in the Wet Mountains and Sangre De Cristos.

The streams and valleys they trapped are part of the historical recreation tour of the San Isabel. Smith Creek in the Hardscrabble Canyon near Wetmore on Highway 96, the National Register-listed Squirrel Creek Campground near Beulah and the St. Charles River at Lake Isabel on Highway 165, are examples. Beaver, once nearly hunted to extinction, are now back in force, and can be watched from many road-side locations hard at work repairing and building their dams.

A beaver dam on Greenhorn Creek near Colorado City, just east of the Spanish Peaks. Date unknown.

Soon after the Louisiana Purchase, Lt. Zebulon M. Pike was sent west in 1806 to explore the southern boundaries of the “Purchase.” Pike was the first of many American explorers who traveled through the San Isabel. Those who followed Pike include: Major John C. Fremont, whose 1848 route west took him through Hardscrabble Canyon and the Wet Mountain Valley; Lt. George Wheeler, who surveyed the Spanish Peaks area between 1869-79; and Dr. Ferdinand Hayden, who accomplished the first thorough survey of the region in 1870.

The Homestead Act of 1862 would forever change the face of the west. The act allowed any citizen who was at least 21 years old to obtain 160 acres of land. To get the land, the homesteader had to live on the property for five years, farm the land, build a home, make improvements and pay a small fee. In 1873 the act was modified to increase the acreage.

Many of these old homesteads formed the nucleus of large ranches, still visible today, such as the National Register-listed Beckwith Ranch six miles north of Westcliffe on Highway 69. The derelict remains of less successful homesteads can be seen from Highway 165 just north of the Bav-R-Li Lodge and as the nearby intact Mingus Homestead, also accessible from Highway 165. These high-country homesteads endured an average frost-free growing season of only 78 days. It is no surprise that most homesteaders failed.

After gold was discovered near Denver in 1858, the big rush was on. In 1872 gold and silver were discovered in what would become the towns of Rosita and Querida (near Highway 96). Many exploratory pits and mine shafts can be seen along the tour route. Some are obvious, but many others require a sharp eye to locate. Test your spotting skills on South Hardscrabble Canyon Road, west of the Civilian Conservation Corps camp site on Forest Road 386.

Ore Smelting and the arrival of the railroads in Pueblo in 1872 resulted in the region’s burgeoning importance as a mining and industrial center. By 1900, the availability of iron ore and coal, combined with easy railroad access, had made Pueblo the “Pittsburgh of the West.” With a population of 50,000, Pueblo was the second largest city in the Rocky Mountain West and the industrial and transportation hub for all of southern Colorado.

The Guggenheim and Rockefeller families bought controlling interests in Pueblo’s smelters, new steel mills and nearby coal mines. By the start of the 20th century, the Colorado Fuel & Iron Corporation (CF&I) was Colorado’s largest company. In 1920, thirty percent of Colorado’s payroll dollars went to CF&I steel mill workers in Pueblo, and to its coal mine workers in Walsenburg, Aguilar, Trinidad, Florence, and Coaldale. The CF&I was Colorado’s largest private landowner. The company owned or controlled more than 500,000 acres of land, most of it south and west of Pueblo.

The CF&I employed 30,000 mill workers and miners. Of these, an estimated 15,000 were immigrants who, along with their families, were recruited by the company, primarily from Bohemia, Italy, and eastern European countries. These workers lived in company-owned houses in more than 30 “company towns” south of Pueblo. Mill workers in Pueblo typically owned their own modest dwellings. Many of these are still extant, and can be seen in many sections of South Pueblo.

Labor Strife

In the early 1900s, efforts began to unionize the largely immigrant CF&I workers, which led to violent confrontations between the workers, the mine owners, and the organizers. By 1914, an estimated 100 lives had been lost in the struggle. On April 20, 1914, at Ludlow junction, company guards opened fire with machine guns on a workers’ tent camp filled with families and subsequently burned the colony. Eleven women and children and several bystanders were killed in the incident, which became known as the “Ludlow Massacre.”

After the massacre made international news, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. took action to stop the violence. His chief of staff, McKenzie King, negotiated an agreement with the union. The agreement, called the “The Rockefeller Plan,” became a model for similar labor-management negotiations across the country.

An eight-hour workday was established at the CF&I. The agreement included provisions that the CF&I would establish healthy recreational outlets for workers, including outdoor recreation opportunities.

One example was Whispering Pine Camp, located by Stonewall in the Mountains west of Trinidad near Highway 12. The camp was built by CF&I in 1918. It was built for the summer use of boys and girls from surrounding company coal mine towns and camps. Young people from the Pueblo steel mill families may also have “gone to camp” at Whispering Pines.

Roots of Mountain Recreation in the San Isabel

As early as the 1800s, the people of southern Colorado were using the mountains west of the hot, dry plains for recreation. In those early days there were only a few mountain visitors. Those few who came camped, hunted or fished. They brought their supplies with them by horse and wagon. Sometimes they attached a simple tent sheet to the back or side of the wagon for shelter. The campsites were the same kinds of places visitors use today: pretty surroundings with water and road access nearby.

In the 1880s and 1890s, getting to the mountains from even nearby towns like Pueblo or Trinidad was hard. The roads to the Wet Mountains and Spanish Peaks were rough, unimproved wagon trails. A few rocky roads, almost ruts, climbed up steep canyons like Hardscrabble and Squirrel Creek into the mountains where they often dead-ended. These early mountain roads sometimes must have seemed worse than no road at all to the early high-country homesteaders who were their main users.

A sign marking an entrance to the San Isabel National Forest at the top of Cucharas Pass. 8 July 2017.

In 1895, Fanny Harper’s family came from Blue Bell, Kansas, to homestead at Bigelow Divide on present-day Highway 165. The homestead was at 9,500 feet. In 1993, Fanny recalled that the wagon road went down the mountain from her parent’s homestead to Beulah and “crossed Squirrel Creek 26 times.” Fanny related that it was “easier to go down the middle of the creek, than use the road.”

Beginning in the 1880s, well-to-do families from Pueblo and Trinidad — like the Whites, who owned White’s Department Stores, and the banking and ranching Thatcher family — built summer cabins in the nearby mountains. Many of these early recreational cabins are still in use and can be seen in and near small mountain communities like Rye and Beulah, located at the base of the Wet Mountain Range.

Near the turn of the 19th century, several small tourist hotels were built in Beulah. They catered especially to out-of-town visitors. Day trips by horse-back into the mountains were popular to spots like North Creek Divide, with views of famous Pikes Peak, and to Dome Rock in Squirrel Creek Canyon. The Alta Vista, the Antlers and the Davis House are examples of these early tourist hotels. None are left today.

Beginning in the 1920s, the tourist hotel role was filled by motor camps and motels that spread across America with the advent of the affordable automobile. In the 1960s, bed and breakfast establishments also began to appear in Beulah, Rye, Walsenburg, Trinidad and La Veta.

Mountain resorts were also important in the history of mountain recreational development in the San Isabel area. Some resorts, like the 1879 Sulphur Springs Resort near La Veta, were built because they were located near hot mineral springs, and were accessible by railroad. Wagon “taxi” service was provided to and from the property by the resort’s proprietors.

View of the Wet Mountain Valley in the San Isabel National Forest, shrouded in a morning mist. 27 June 2004.

In even earlier times, Native American people used the springs for health, and for relief from the cold winters. Many of their artifacts have been found nearby. (Remember, feel free to take pictures but leave any artifacts you might find.)

Other small mountain resorts, like Cucharas, located on present-day Highway 12, were built high in the mountains in the early 1900s. They were accessible by wagon or automobile. Sometimes wagon roads were built just to allow resorts to be built. One example is in the Alvarado area west of Westcliffe. In 1920, the Forest Service, in cooperation with a resort developer, built an automobile-accessible, 1.5-mile road to open the area to development.

The high-country resorts in the San Isabel area were small in comparison with the large expensive resorts being built in popular tourist destinations at places like Pikes Peak near Colorado Springs, and near Rocky Mountain National Park north of Denver.

In contrast, resorts like the Bav-R-Li Lodge on present-day Highway 165, or the Alpine Lodge west of Westcliffe, typically had one main log or milled lumber dining and meeting building, five or six small rustic cabins for lodging and perhaps a bathhouse. Sometimes campsites could be rented with the understanding that the “campers” would eat their meals at the lodge.

A typical room and board fee was $1 to $3 per day in 1920. As inexpensive as this seems to us today, even these modest resorts were out of the price range for most local people in Pueblo and Trinidad.

Our understanding of the early origins of mountain recreational development would be incomplete without mentioning the importance of camping and picnicking at informal, undeveloped campsites.

By 1918, it is estimated there were two million automobiles in America. By 1920, that number had increased to more than three million. Many working-class Americans, including those in southern Colorado, had real mobility for the first time. They could travel to the mountains on a hot weekend day.

Cross-country travel was undertaken only by the adventurous. But day-trips or weekend camping was now possible for nearly everyone. Following the war, Americans also had a greater interest in visiting the outdoors. Many Americans also had more leisure time because of shorter workdays, and shorter workweeks.

In the ‘teens and early 1920s, many southern Coloradoans enjoyed their free time and mobility by traveling to the eastern slopes of the Wet Mountain Range, the Spanish Peaks and the Culebra Mountains west of the Spanish Peaks. They selected likely picnic and camping sites. While there were no improvements or facilities, the sites almost invariably offered water, good scenery, and automobile access.

There were hundreds of informal campsites, often located on stream banks, by beaver ponds, and at especially scenic sites where the roadway, often not much more than a wagon road, allowed enough space to park a car and set up a small camp. Meadows next to a mountain stream were prime locations.

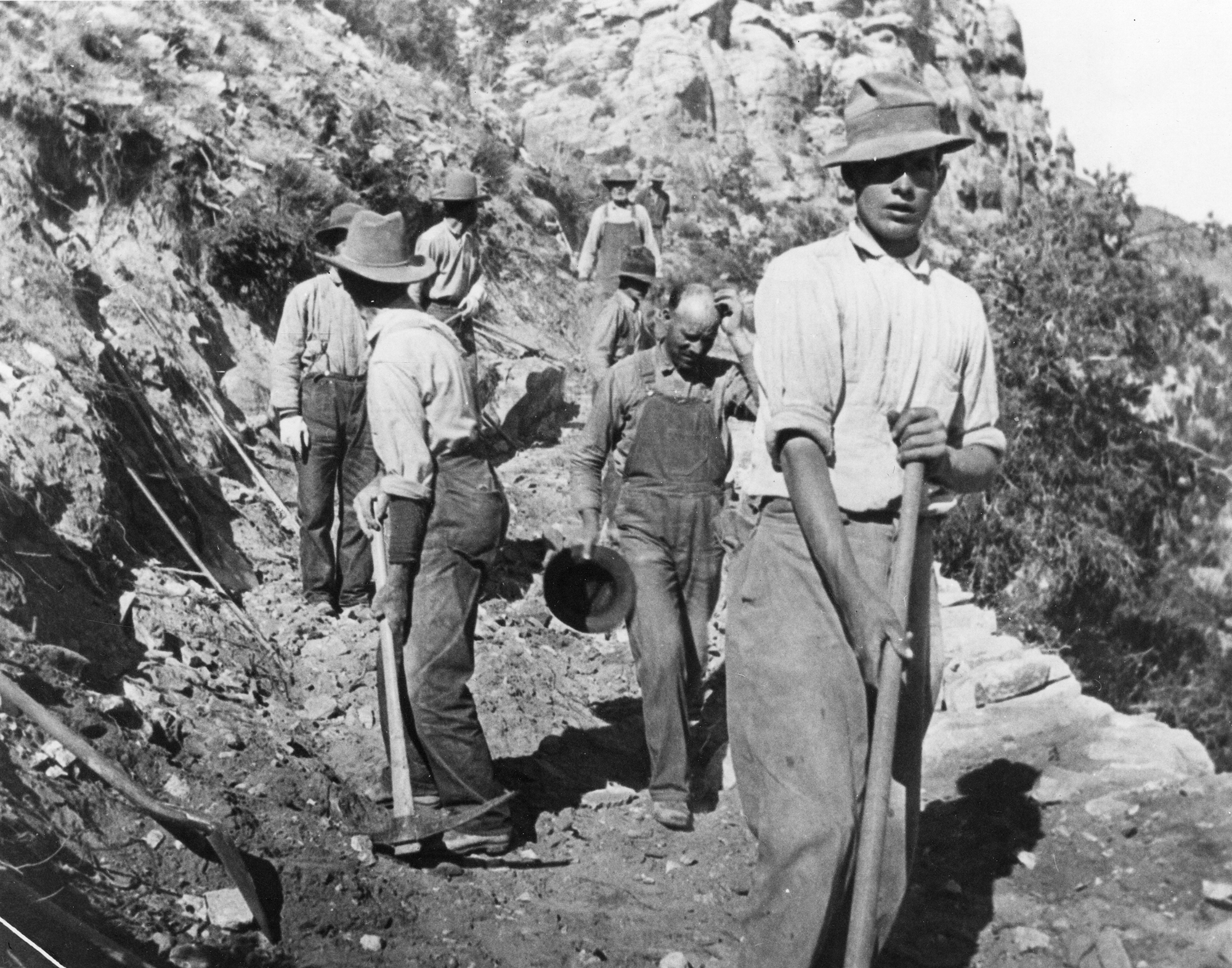

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers constructing a road in the Colorado mountains, 1930s.

Undeveloped campsites are still seen throughout the San Isabel. Many are still used. You can spot them by packed dirt tracks, leading perhaps 10 to 50 feet from the main road. They are usually marked by round, loose rock “fire rings.” It is likely that many informal campsites and fire rings have been in the same place for generations. A good example is in the Hardscrabble Canyon on Highway 96 just west of the Smith Creek Campground.

Undeveloped campsites were all that was available to these temporary visitors after World War I: There were no developed campsites. Unfortunately, informal campsites were often on private land. And sites on San Isabel National Forest presented problems, too. Unsanitary conditions, trash, and the threat of forest fires were worrisome to forest managers. These issues would begin to be resolved only when the Forest Service began formal campsite planning and development of improved campsites and campgrounds in 1919.

San Isabel National Forest:

The beginning of forest planning

The San Isabel National Forest is enormous. It stretches all the way from the New Mexico-Colorado border on the south to Leadville on the north, a distance of 250 miles. On its eastern side, the forest borders the industrial city of Pueblo and smaller towns such as Walsenburg and Trinidad.

After WWI, thousands of visitors flocked to the mountain slopes in their newly bought cars. Where state roads ended, campers and picnickers set up informal campsites near villages such as Beulah, Rye and Stonewall. In 1919, there weren’t roads into the forest, apart from service roads not designed for automobile use. Campers cut down trees for firewood on private land. Trash (and worse) littered the area. Streams like Squirrel Creek and South Trujillo Creek were polluted, a great concern to civic leaders in downtown communities. Uncontrolled campfires were a constant threat.

In 1919, it was clear to San Isabel Forest Supervisor Albin Hamel and to community leaders in nearby towns that recreational pressure on the forest was inevitable and growing. Something had to be done to open the forest to campers, and to provide them with sanitary and safe facilities.

In 1919, Forest Service managers in Washington, D.C., were just starting to realize the recreational dilemma they were facing across the country. Cities with large populations close to national forest (Pueblo, Portland, OR, and Los Angeles, CA, in particular) were of special concern. The national forests had first been set aside from homestead development, starting in 1891, when they were called “forest reserves.” The forest reserves were created by Congress in response to the growing concern that the nation could soon lose its timber supply as people and timber companies moved west in even greater numbers. In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt created a new agency called the Forest Service to give greater focus to forest reserve management. In 1907, the chief forester, Gifford Pinchot, renamed the forest reserves “national forests.”

The national forests were managed for timber production, watershed control, and livestock grazing. Recreational use by the public had not been anticipated. The National Park Service was created in 1916, primarily to address recreational use of public lands. Many leaders in Congress and in the Forest Service believed the new national parks were solely responsible for recreational development. But creation of the new park system did little to alleviate visitor pressure on the national forests in places like Pueblo and the San Isabel.

Forest Service managers in Washington, D.C., belatedly realized that a response to the National Park Service’s virtual monopoly on recreational development of public lands was a threat to the future of the Forest Service. Every new park created by Congress was carved from national forest land. And there wasn’t a single dollar allocated in the Forest Service budget for recreational uses of National Forests. While forest managers now understood the need for recreational improvements, there was no money to pay for them. And there was no one in the service with professional expertise to plan and build them.

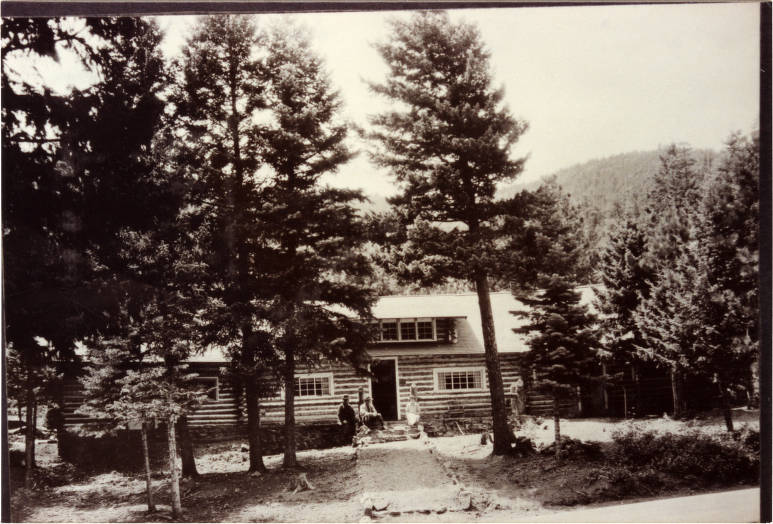

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers building one of the cabins at the Beulah Mountain Park in the 1930s.

The Forest Service Responds

In 1918, facing competition for land and budget from the National Park Service, the Forest Service asked the eminent University of Massachusetts landscape architect, Frank A. Waugh, to conduct a recreational study of the service. Dr. Waugh spent the summer traveling to many of the national forests around the country.

Dr. Waugh’s 1918 report to the Forest Service concluded that recreation, such as camping, was a valid use of the forests, that recreation has a dollar value just like timber production, and that the service should hire professionally trained landscape architects to plan and develop recreational facilities in the forests.

The Forest Service responded quickly to Dr. Waugh’s recommendation to hire a professional landscape architect, or “recreational engineer,” as they preferred to call the job. On March 1, 1919, the service hired its first recreational planner, Arthur H. Carhart.

Twenty-six-year-old Arthur Carhart was recently discharged from the Army, where he had served as an army camp designer and sanitation engineer. In 1916, he graduated from the Iowa State College (now Iowa State University) landscape architecture department. After graduation, he worked as a landscape architect with a leading Midwestern landscape architectural firm in Chicago. While there, Carhart did park and city planning work. His credentials for the new Forest Service job were prefect.

Assistant Chief Forester Edward Sherman interviewed Carhart. He was impressed with the young man’s energy and enthusiasm. If Carhart were a success, Sherman hoped to hired additional landscape engineers if money was available.

But when asked by Sherman, nine out of ten of the agency’s district offices said they would prefer to spend their funds on an additional forester, not on a “beauty doctor.” District 2, which included the San Isabel National Forest where Supervisor Hamel worked, was a different story. Hamel and his supervisors in Denver immediately agreed to bring Carhart into the district. Carhart would be based in Denver but would work in San Isabel and the other 21 national Forests in the districts as needed.

The Lodge at Lake Isabel Recreation area, circa the 1930s.

Forest Supervisor Hamel and Arthur Carhart hit it off immediately. Hamel saw in Carhart a possible answer to the recreational issues he faced. In Hamel, Carhart found a dedicated, forward-thinking Forest Service officer who, unlike most of his peers, understood the importance of recreational planning and development to the future of the Forest Service.

Forest Service Recreation Planning

Carhart toured the San Isabel National Forest with Hamel in March 1919. Carhart proposed some radical changes, using the San Isabel as a model for the rest of the nation. They included everything from the concept of integrated planning of new automobile roads to cabins, trails and lookout points for scenic viewing.

Hamel and Carhart encouraged local support of Carhart’s ideas. Pueblo businessmen founded the San Isabel Public Recreation Association (SIPRA). Businessmen south of Pueblo in Trinidad, Walsenburg and La Veta formed the Spanish Peaks Mountain Playground Association, modeled on SIPRA.

With private funding for recreational development assured (there was still no Forest Service budget for recreation), Carhart, by December 1919, developed a rationale and 450 pages of recreational plans that covered 650,000 acres of forest recreational improvements in the San Isabel. This comprehensive plan, the first in the Forest Service, became known as “The San Isabel Recreation Plan.”

Carhart stated that forest recreational plans should be “big and broad.” He believed that all recreational units in a forest should be interconnected and that it was essential that all units should be connected by good automobile roads. His plans also provided for complete campsite units that included a permanent fireplace, latrine, garbage disposal unit, and a well and pump for clean water.

Carhart laid out, for the first time in forest history, the idea of levels of usage of the forest, ranging from heavy-use areas such as group picnic grounds and cabin communities, to wild areas that would be left undeveloped forever. His “zoning” approach to large-scale forest planning provided the groundwork for later forest planning concepts such as multiple use and the wilderness program.

Carhart sited more than thirty developed campgrounds in the San Isabel and proposed and sited 225 miles of new roads to connect them. A forest visitor could choose one or more loop tours and travel throughout the entire 7,500-square-mile area without ever needing to double back.

In his short time with the Service (1919-1922) Carhart personally designed and supervised the construction of Squirrel Creek Campground, Squirrel Creek Road, North Creek Campground, North Creek Road and South Hardscrabble Campground. He sited and oversaw the placement of the first improvements on the 600-acre Pueblo Mountain Park. Although the park would be city-owned, Carhart recommended its establishment and its location. He noted that municipal parks should be developed in conjunction with Forest Service camps.

Carhart’s first experimental development was Squirrel Creek Campground west of Beulah. His work here was watched with great interest by Forest Service managers in Washington, D.C. If Carhart, with the financial assistance of SIPRA, made a success of this first ever architect-designed national forest campground, then the Forest Service could possibly compete successfully with the powerful and popular National Park Service for future recreational funding. The stakes were high.

Squirrel Creek Campground was a resounding success. It opened in June 1919, with ten developed campsites. On its first weekend, 750 cars were counted at the campground. In subsequent weeks, a family representative would “stake out” a campsite a day or two in advance in preparation for a weekend visit by the entire family. Over the winter and spring, thirty-two more campsites were built in the campground. The response was equally impressive in 1920.

In 1920, the North Creek Campground and South Hardscrabble Campgrounds opened to an equally enthusiastic response. Visitors to the three campgrounds were mostly from nearby towns like Pueblo, Florence, and Canon City. However, campground guards also recorded visitors from eleven states and three foreign countries.

Despite the success of the early campgrounds, the Forest Service was unable to convince Congress to provide funding for campground and other improvements. As late as 1928, the budget for the entire Forest Service recreational program was only $41,000. This small amount had to meet the needs of 160 national forests on 180 million acres.

Arthur Carhart, realizing there was no future for his kind of professional planning work in the Forest Service, left the agency on December 31, 1922. His campground and road building plans were completed over the next twenty-five years. With the help of SIPRA and the Spanish Peaks Mountain Playground Association, the San Isabel National Forest in the 1920s became the leading “recreational” forest in the nation.