Story

Festival of the Mountain and Plain

The popular but short-lived “Mardi Gras of the West” has much to tell us about Colorado’s history, culture, and people at the turn of the 19th century.

A brass souvenir badge from the 7th annual Festival of the Mountain and Plain.

Several months ago, during my first week working as a collections intern at History Colorado, I opened a small archival sleeve labeled “78.151.30––Souvenir pin.” Inside was a brass pin with the inscription, “MOUNTAIN & PLAIN FESTIVAL, DENVER, 1901.”

The ornate pin piqued my interest, and made me want to know more about this festival from long ago. Branded as a spectacle that would “eclipse anything of the kind ever attempted in the West,” the Festival of Mountain and Plain was a combination exposition, carnival, pageant, and rodeo that ran in the heart of Denver from 1895-1902. With discounted railroad tickets advertised across the Great Plains and beyond, the event pulled in hundreds of thousands of visitors to see Colorado’s industry, history, and people on display each October. It was, in essence, the “Mardi Gras of the West.” Like Mardi Gras, the World’s Fair, and countless other flashy festivals, however, there is much more nuance to the Festival of the Mountain and Plain than surface-level fun.

A large, colored advertisement for the festival featured in the Rocky Mountain News, 1901.

Colorado’s economic entanglement with silver is a throughline in the parade’s history, both as an economic impetus for its creation and a central theme in the celebrations themselves. Though the gold rush is well-known for its crucial role in putting the West on the map, silver’s importance in Colorado history looms far larger. Longer-lasting and more lucrative than the gold boom, the silver boom in Colorado forged millionaires like Horace Tabor and Margaret “Molly” Brown, created thousands of jobs, and spurred the laying of new railroads across the state.

But following the silver crash of 1893, Coloradans were in trouble. Colorado's unemployment rates were the highest ever, and the economy fell into a deep depression. So, why throw a massive, expensive festival just two years later, and where did the funding come from? Most of the larger mines managed to stay afloat despite the silver crash by consolidating resources. Their wealthy owners monopolized the industry before national restrictions on such practices were put in place. The economic void left by the devastated silver industry also allowed space for growth in other areas, allowing Colorado’s agricultural and manufacturing sectors to grow exponentially in the years following the crash. As whispers of a lavish festival made their way through Denver in 1895 there was enough enthusiasm among Denver’s elite to make it happen, despite the ongoing depression, which did not come to an end until 1897. A festival provided the perfect opportunity to draw much-needed tourism and investment in the struggling industries.

Portrait of the “Queen of the Festival” Ruth Boettcher Humphreys, 1912.

The wealth and fervor poured into the Festival of Mountain and Plain was truly unparalleled in the West, capturing the region’s imagination similarly to the popular exhibitions and World’s Fairs at the time. Newspapers across the state described floats costing tens of thousands of dollars, costumes specially ordered from Paris, and elaborate balls held at the Brown Palace Hotel. The gowns of the “Queen of the Silver Serpent” and gem-studded, silver tiaras reflect the immense wealth and energy procured by this social organization, poured into such a parade each year.

One of the most interesting aspects of the event was the air of mystery surrounding the so-called (and insensitively named) “Slaves of the Silver Serpent.” Modeled after the Mardi Gras parade “Krewes” of New Orleans, the Slaves of the Silver Serpent were a secretive group ostensibly composed of Denver’s most elite businessmen. They designed and built floats, threw galas, and elected royalty for their parade each year. However, unlike New Orleans, this was the sole “krewe” of its kind.

Behind the splendor of the Slaves of the Silver Serpent, their costumes, galas and secrets, is the far less appealing history of where their collective wealth came from: a gruesome underbelly of exploited mine and railroad workers, abused legal loopholes, and brutally displaced Indigenous communities. While newspapers from the time hailed these actions as necessary steps towards “progress,” a more expansive contemporary view on the matter recognizes the violence inherent in that perspective.

Indeed, inseparable from the surface-level beauty and opulence of the festival was the sensationalization of all things “Frontier.” One parade, entitled the “Pageant of Progress,” provides a vivid example of this:

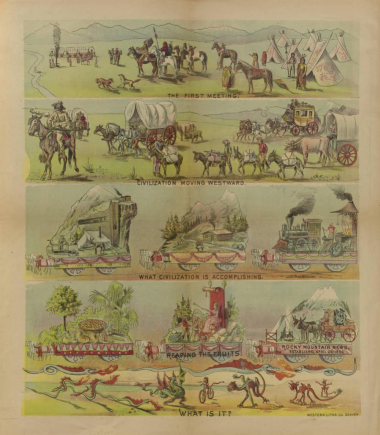

A print detailing the “Pageant of Progress” Parade, printed in the Rocky Mountain News.

“The distinctive feature of yesterday’s programme was the parade of the Pageant of Progress, the faithful and detailed story of the rescue of an empire from barbarism and its transformation and development to a wealth and civilization not surpassed in this or any other nation… The Indians were there in person as ferocious in appearance as in the days when they were the dread and deadly enemies of the hardy pioneers with whom they marched yesterday, playing their part in a historic drama not possible on any other stage.”

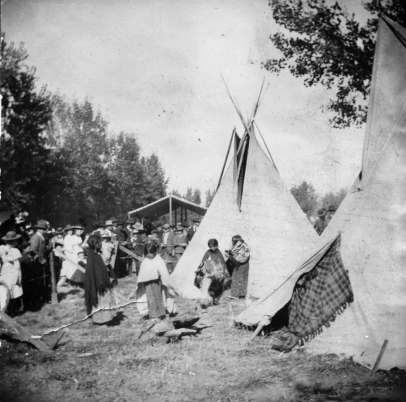

Ute children observed by parade-goers in City Park.

Chinese Americans and members of several Indigenous Tribes were invited to participate and given their own parades, but they were presented to parade-goers as a small part of Colorado’s history, sideshows on the journey to “civilization” and “development” led by white pioneers, miners, and businessmen. In one photo, several Ute children are depicted camping in City Park while white parade-goers look on from behind a fence. Newspapers describe the Apache as “warlike” and the Pueblo as a “mysterious tribe of idol-worshippers.” One float depicted the massacre of a white pioneer family by “a band of prowling Cheyennes.” It is clear this inclusion was intended more as a spectacle than a show of respect for the cultures and people themselves.

After eight years, the final Festival was held in 1902. There was one failed attempt at revival in 1912, but Colorado has not pursued something of the same magnitude as the Festival of the Mountain and Plain since.

Despite its short life-span, the Festival can still teach us a great deal about the people of Colorado at the time. On the one hand, records of this event present an incredibly valuable, specific view into that era of Colorado history, allowing us to critically examine the individual tidbits left behind. The other side of that coin is that the variety of perspectives on the event is quite narrow, mostly limited to that of the white, wealthy elite in charge of organizing and advertising the Festival.

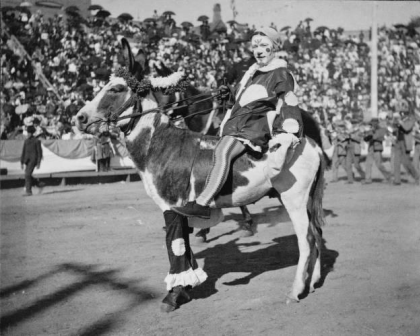

A costume-clad parade-goer and her “mighty steed.”

At a base level, the Festival of the Mountain and Plain was no more than a fun celebration of Colorado history and culture, but a closer examination speaks to the ethnocentrism and ignorance baked into the version of history it presented to the public.

Despite the narrow perspectives presented by the Festival and other events and records of the time, the beauty of archives––especially those available digitally––is that so many of us now have access to more than just these limited peepholes into history. We can research disparate events, times, and people and apply our own experience to expand our collective understanding of the past. As the digital realm grows ever-larger, it is important to recognize the privilege of this access and the importance of not just consuming this information, but critically engaging with it.