Story

Uncle Doc: A POW’s Story of Survival, Compassion, and Hope

Jack Comstock, MD, graduate of the CU School of Medicine, kept a diary for three years, from late 1941 to early 1945. In that diary is a powerful tale of survival, compassion, and hope: the only known real-time journal of a POW doctor in World War II.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in a five-part series. It has been adapted, with minimal changes for readability, for The Colorado Magazine. The original can be found here on the CU Anschutz website.

As dawn broke over the South Pacific on Sept. 21, 1944, Jack Comstock, MD, stepped out of the officers’ quarters on his callused bare feet, wearing a G-string and little else. He stared at the specks on the pale horizon.

The dots moved slowly, diffuse at first, nothing more than a distant whine. Then they gathered into something else and met his ears with a thunderous roar. Comstock’s heart thumped.

He reached for a scrap of rice paper and clicked open his pen. He scribbled down his thoughts as he often did. His words usually chronicled accounts of disease, despair and death. Not this time.

“American planes, both bombers and pursuits, flew in from the Pacific,” Comstock wrote. “These flights were the most thrilling, exciting thing I have ever seen. Probably because it meant so much to all of us. So far, the planes have not returned, but we all hope they will soon.”

He had waited for this moment almost three years.

That’s how long Comstock, a 1938 graduate of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, had been held captive in World War II. By that fateful morning in September 1944, his nightmare in the Philippines was nearly over.

Comstock retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1957 because of a physical disability, completing twenty-one years of military service including 16 years in the Medical Service of the Army and Air Force. In 1945 he was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions as ward surgeon during the assault on General Hospitals #1 and #2 on the Bataan Peninsula before his capture by Japanese forces on April 9, 1942.

A trio of qualities steeled the young doctor to survive 34 months as a prisoner of war (POW) on Luzon Island: the hope of returning to the beautiful Boulder Valley and his family, devotion to his patients and sheer force of will.

The journal entry about the U.S. planes marked a pivot: It was the moment Comstock’s spirits surged with an unfamiliar, yet palpable, vision of freedom and brighter days ahead. Could the brutal war and his hellish imprisonment finally be coming to an end?

By that time, Comstock had witnessed countless atrocities, seen hundreds die, treated scores of gruesome tropical diseases, battled boredom and despair, fought off a bout of dengue fever and noted the wasting of his own body (he lost over 50 pounds as a prisoner) – all while keeping alive within him the faintest embers of hope.

Edward Kinzer, MD, a fellow CU SOM alumnus (Class of 1952) who has treated prisoners of war in Africa, said Comstock, and especially the enlisted servicemen who were POWs in the Pacific Theater, experienced unspeakable horrors. “Decapitation, emasculation,” he said. “In one instance, (the captors) bayoneted a pregnant woman and removed her infant in utero. All kinds of atrocities—the worst you can imagine—occurred.”

As each day unfolded with misery, uncertainty and unrelenting hunger, Comstock had reached for a pen or stubby pencil, risking his life by scrawling notations. His vivid writings remain the only known journal to survive undetected in a WWII Pacific Theater prison camp.

A Rare Journal

In Comstock’s later years back in Colorado, he received medical care from Steven Oboler, MD, then-POW physician coordinator at the Denver VA Medical Center and a SOM associate clinical professor of medicine. Oboler learned about Comstock’s piecemeal journal in the early 1980s.

“I was gobsmacked,” he said, pointing to the 130-page stack of transcribed writings. Oboler had read many “diaries” from Pacific Theater survivors of WWII, including ones written by physicians, but they weren’t daily, real-time accounts. “When he brought in this, the typed copy, I was just absolutely amazed…. I was in awe that he could possibly do it.”

The transcribed diary, thanks to a donation by family members who still live in Boulder, is now available for digital viewing (part one and part two) at the Strauss Health Sciences Library at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. The original diary—a collection of dated, hand-written notes—is housed at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Kinzer, who also served in the U.S. Army Air Corps, nominated Comstock for a Silver & Gold Award, the most prestigious CU alumni award. It was presented to Comstock’s family at a campus-wide ceremony on May 26, 2006.

“He was at great risk if he’d been discovered writing his diary,” said Kinzer, who lives on a family farm near Johnstown. “I’m not sure where he kept the journal up to a point. He secreted (the entries) here and there, when he thought he was going to be transferred to Japan on a hell ship for slave labor purposes, which never occurred. But he was prepared to secret them in case he had to.”

Every day, he found the strength to describe not only what was happening, but how the events affected both himself and the men. He typically scribbled his thoughts on rice papers that came with medications, each about the size of a gum wrapper, as well as on the backs of can labels and packaging labels from POW boxes.

Shortly after the Japanese occupied the general hospital, located at the tip of the Bataan Peninsula, where he was ward surgeon, Comstock wrote: “We were awakened early this a.m. (still dark) by Japanese going bed to bed in the officers’ quarters searching everybody. Got a clock, watch, ring. Nothing from me. Reports that the road to Manila is practically lined with dead—mostly Filipinos. Sure do miss the news. Wouldn’t mind a good meal.”

A month later, when Corregidor Island, a US stronghold coveted by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, was on the brink of surrender, the doctor couldn’t contain his exasperation: “Same flies! Same heat!” he wrote on May 6, 1942. “Same lack of news! Same monotony! Same weakness! Same everything!!! … Wonder when we are getting out of here and into what.”

Uncle Doc, as he was called by his family, didn’t aggrandize his actions, though he could have. Medical personnel, who also suffered significant mortality rates during the war, were easily the most important people in the lives of POWs.

Comstock’s selfless actions giving medical treatment to other prisoners helped hundreds of others survive during the Pacific Theater of WWII, which saw some of the most brutal treatment of POWs in the annals of modern warfare. His compassion, smarts and work ethic—forged during an upbringing across the Great Plains and in the shadow of the Flatirons—showed through in the diary entries.

In many ways, Comstock, who lived happily in retirement in Boulder until his death in 1996, embodied the American ideal. His is a remarkable survivor’s story, and it starts with a foreshadowing entry in his diary on the day before the American and Filipino defenders of Bataan were ordered to surrender:

“April 8, 1942: Nice day. Air raids right after breakfast. Many, many patients all day. Few casualties, but mostly malnutrition, exhaustion and nerves. Nurses sent to Corregidor (Island) about 10 p.m. We are to stay to run the hospital. No front lines! We are sunk!”

Day of Infamy

Jack Comstock, MD, was living out his dream in the South Pacific in late 1941. He had achieved his goal of becoming a doctor, joined the Army and landed an attractive peacetime post – attending surgeon at Sternberg Hospital in the Philippines.

In his late twenties, the Fort Collins native and University of Colorado School of Medicine graduate evinced charisma and confidence. Handsome and athletically-built, the dimple-chinned doctor was Bogart-esque in his Army uniform.

As a physician, Comstock displayed a compassionate, yet no-nonsense, demeanor during his rounds at Sternberg. “I think he was probably a pretty tough taskmaster, and he could not take a goldbricker,” said Jim Kilburn, a relative of Comstock’s from Boulder.

Jacquie Kilburn, Comstock’s niece, recalled that Uncle Doc was on a debate team at Boulder Prep (now Boulder High School). “And they won everything they ever did,” she said. “I just think that it wasn’t a choice for him. He would do the best he could no matter what. And he would expect the best of anybody else—as much as they could.”

That same drive for excellence set Comstock apart as he went on to earn honors in chemistry at CU Boulder, then graduate in 1938 from the CU School of Medicine and start his first medical position in 1941 at Fitzsimons General Hospital on what is now the CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

Comstock was on a track to both academic and military success. But everything unraveled on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941.

The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service bombed the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing 2,403 and thrusting the United States into war. Simultaneously—eighteen hours ahead—200,000 Japanese attacked the Bataan Peninsula.

Comstock was shifted to a ward surgeon post on Bataan, where American and Filipino forces battled the Japanese for control of the peninsula and the nearby island of Corregidor.

Comstock was plunged into the center of an epic battle, one that US Gen. Douglas MacArthur erroneously thought the US could win. At just one of the hospitals, 6,500 patients suffered war injuries, malnutrition and tropical disease. By early April 1942, after four months of intense fighting, the US and Filipino forces surrendered Bataan to the Japanese.

Shelling continued for several weeks before the Japanese took Corregidor, a speck in Manila Bay.

“(Before the surrender) Corregidor was firing back, and the hospitals were right in the way,” said Steven Oboler, MD, the POW physician coordinator at the Denver VA Medical Center, where he first met Comstock in 1983. “A number of times there were explosions, and patients and staff were killed by shrapnel and bombs. It was not a safe place to be.”

On April 29, 1942, Comstock wrote in his diary: “This morning Corregidor sure took and gave Hell. By far the worst artillery duel so far. Shrapnel was falling like hail around the Receiving Ward. Believe me, we all kept in our covered fox holes or screened by bamboo thickets.”

Taken Prisoner

The end of freedom was swift but brutal.

“Much air and artillery activity this morning. White flag hoisted at 10 a.m. Don't like it at all. Red Cross flags hung all over hospital,” Comstock wrote on April 9, 1942. “(Enemy) came in after dark. No more washing in creek, no smoking after dark, must use blue-colored flashlights at night. Death penalty if not complied with. Wonder about all sick and wounded at front lines with no one to bring them in.”

Conditions worsened as the Japanese rounded up about 80,000 U.S. and Filipino prisoners of war, forcing them to march seventy miles to prison camps, including Camp O’Donnell, in the north. The infamous Bataan Death March cost the lives of nearly 16,500 Filipinos and about 650 Americans.

“Dr. Comstock never went to Camp O’Donnell,” Oboler said. “There were 75,000 Americans and Filipinos at Camp O’Donnell, and the death rate was just horrendous.” Brutal conditions resulted in approximately 1,500 deaths of the 8,000 Americans interned there during the first six months.

“The Japanese realized that they had to do something about it,” he said. “They needed slave laborers, so letting the POWs die of starvation and disease was not in their best military interests.

“That’s where Cabanatuan—POW camps #1 and #3—came into existence,” said Oboler, noting where Comstock ended up. “They were much more organized. They used some public health measures including covered latrines and better access to clean water. Even still, the number one work detail was burial detail.”

In early May 1942, Comstock’s medical detachment from the general hospital—a group of several hundred doctors, male nurses, orderlies and lab technicians—was told it was moving north along the peninsula. On May 11, the group rode buses to Little Baguio: “What a scene of ravage and desolation along the road,” Comstock wrote in his diary, referring to the remains from the Bataan Death March, which the Japanese army had carried out strategically to lower the number of POWs it had to manage. “Skeletons, stinking to hell, strung along. So much waste and destruction!”

Later that month, the medical unit rode trucks to San Fernando before the convoy continued to a stopover at Bilibid Prison. Finally, the unit boarded a train bound for the outskirts of Cabanatuan, where Comstock would spend most of his imprisonment.

On May 31, 1942, Comstock wrote, “Went east from Cabanatuan. Hiked over ten miles by 11:30 a.m. Very hot. Little rest. Carried a heavy load. Many threw their packs away. Others passed out. Was sure grueling business. I couldn’t have gone much further.”

Managing the Three Ds

Prior to becoming a POW, Comstock had already been documenting his Army experience in a journal. But during almost three years of imprisonment, he remained a diligent diarist, writing entries that would become the only real-time account of practicing medicine as a POW in the Pacific Theater of World War II.

Comstock wrote about the POWs’ daily struggle with disease, death, hunger, homesickness, boredom and the horrors committed by their Japanese guards.

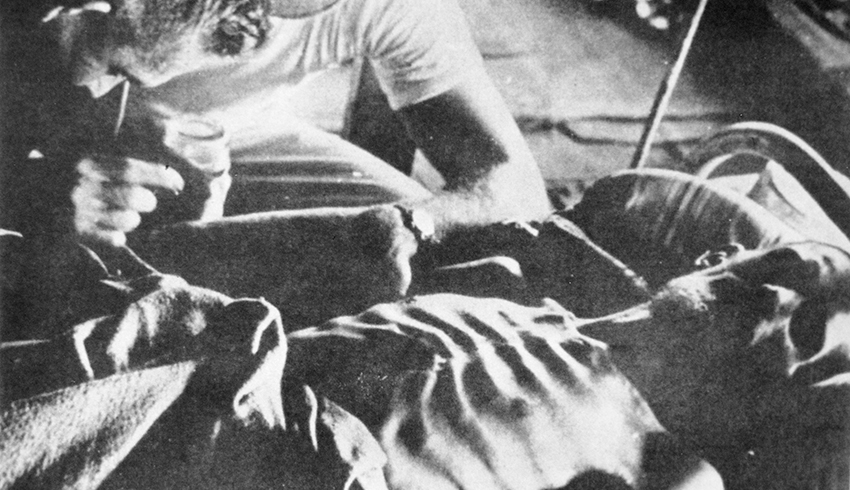

In the POW camp, much of daily life as a physician amounted to managing the “three Ds,” as they were called—diphtheria, dysentery and death. Comstock chronicled the camp’s daily death toll, usually in the first line of each diary entry.

On June 13, 1942, he wrote: “Deaths continue at a rate of thirty or more each day. All Americans. Majority could be saved with proper treatment and medicine. … Fighting in southern Luzon. MacArthur supposed to have broadcast he would be back in Manila before July 4. Many good rumors. No bad news. Am very optimistic about an early deliverance.”

While many diseases ravaged the prisoners, malaria and dysentery were especially rampant, killing thousands early in the war. Quinine used to treat the diseases was in short supply, and deaths skyrocketed in the POW camps.

“When they got (quinine), that knocked the death rate just cold,” Oboler said. “It was good news and bad news. Quinine can treat the acute fever and get the guys feeling better, but unfortunately it’s not a vaccine, so you can get re-infected and have (the disease) go on and on. The other problem (for prisoners) was meat deficiency, protein deficiency. … As the war went on it became more and more of a problem because the prisoners would get some vitamins but they wouldn’t get any meat.”

Every day was an exercise in medical improvisation, trying to keep disease-ridden, malnourished and oft-dispirited soldiers alive.

Comstock learned to improvise during the three months at the general hospitals on Bataan, when shrapnel rained upon his ward and medicines and bandages were in short supply. But the conditions quickly worsened as the war progressed.

“Think about the [Covid-19] pandemic now,” Oboler said. “There’ve been eighteen months and we’ve got vaccines and you hear about the burnout among healthcare providers and first responders. I can’t imagine what it would be like as a POW physician when you don’t know how it’s going to end. You just go from day to day … He had so little to work with, and he didn’t dwell on it. It was just what it was.”

Edward Kinzer, MD, a fellow CU alumnus (Class of 1952) and Air Force veteran, has faced conditions similar to Comstock. Kinzer spent a year in Nigeria and Mozambique in the 1990s, treating many victims suffering from starvation and the atrocities of war.

“It tests your core values as a physician,” he said, “whereby you have to come up with your diagnosis based on your findings rather than on X-rays and other modern conveniences.”

A Leg Saved, a Long-Delayed Note of Thanks

In July 1942, in just the second month of captivity, a soldier was brought into Cabanatuan with a badly wounded and gangrene-infested left leg. Doctors advised that the leg be amputated but Comstock opted to cut the wound open, clean it and fill it with sulfanilamide powder.

He saved the soldier’s leg. Decades later, Jack Bradley wrote Comstock a letter of gratitude.

“I have always been very grateful for this, and upon release from POW camp in Japan while recovering … I tried to locate you but was informed that you were killed when our Forces sunk an unmarked POW ship bound for Japan,” Bradley wrote. “I don’t believe you can imagine my surprise and pleasure last week to find your name and address in the Colorado directory … I wish you a long and happy life.”

Although he later became legally blind, Comstock lived an active post-military life in Colorado. Oboler and Comstock regularly met in the 1980s when Comstock went to the Denver VA Medical Center for his vision problems—caused by histoplasmosis, a condition which stemmed from a weakened immune system during his POW days—and later Parkinson’s disease.

Oboler recalls asking Comstock about Bradley’s case after reading about it in the diary.

“At first he sort of didn’t remember,” said Oboler, noting Comstock’s customary humility. “Then he smiled. He was really proud of it. He couldn’t remember specifics, but he said, ‘Well, at least I saved one soldier.’”

Diary Themes

Uncle Doc’s early scribblings offer a window into themes that would fill his journal for over three years: daily death rates, rampant rumors of how the war was going, pervasive and deadly illnesses in camp, bouts of depression and homesickness, and atrocities committed by captors, often carried out in fits of rage.

Several entries in summer 1942—one recounting a summary execution of prisoners, which was common —were emblematic of his time in captivity:

June 25: Men on my ward rapidly going downhill. … About sixty with chills and fever including dysentery, edema. No medicines or supplies. Epidemic of upper-respiratory disease. I believe one-half will be dead in four to six weeks if no medicine comes. Rumors of great naval battle off Guam. Today ends one month since we left Bataan. … Waiting is sure tiresome.”

June 26: At sundown two Americans and two firing squads of six each were marched to the hospital area. Americans were set on the edge of their graves and shot. Neither fell in as supposed to. One grave was full of water. Four firing squads on the other side. Seven were reported shot, including one Filipino woman. Hope I never have to witness such a thing again.

June 27: Three pats with cerebral malaria will likely die despite giving some of my own quinine. Very depressing situation. How everyone wishes the war would end soon. It is so useless and futile, appearing especially so to us as we believe there is only one possible outcome.

June 30: Death rate increasing again. Nothing to be done about it.

July 6: Depressed tonight. Maybe homesick. News from home would help a lot.

July 11: Announced by Japanese Imperial HQ in P.I. that from now on for every man who escapes, 10 prisoners will be shot.

July 13: More unsubstantiated rumors of leaving. Thirty-three deaths today.

A confluence of emotions dogged Jack Comstock over a period of weeks. And yet he continued, as he did throughout his imprisonment, to let hope seep in.

“You can almost see the signs of death in a person who has lost the will to live,” Kinzer said. “The people who still had the will to live, to eat anything, to suffer any insult to their body that you can imagine, are those who are going to live.”

Kinzer noted that Comstock, as a member of the medical team, received a small stipend from the Japanese – “maybe $20 a month that they could use to purchase stuff from the native population. So, (officers) didn’t suffer some of the diseases and deprivations that other prisoners of war did.”

That was made clear in Comstock’s diary entry on Sept. 23, 1942:

“11 deaths, going up! Only rumor is that we will be paid shortly after Oct. 1 … Only officers will be paid. This will be a sorry situation as it is the patients who need the money and food worse than anyone else. My cold is still bad …”

Summoning the Strength

Mostly, Comstock longed for home. Though he never married, he was devoted to his family in Boulder. His family still has, among the memorabilia and effects of Uncle Doc’s war days, the last letter he wrote home before being captured in 1942.

His somber pre-capture dispatch contrasted with this elated diary entry, in June 1944, upon receiving the first two letters from “Mama”—a full year after she mailed them: “Much family news. Made me very happy,” he wrote. “… Sure wish the Yanks would come.”

Comstock occasionally envisioned his beloved Rocky Mountains transposed upon the South Pacific horizon.

On Sept. 23, 1942, he wrote: “Dreamed of home last night. Everyone but Deuce (the family dog) included. Was very clear. Went back to 1076 12th St. (in Boulder).” He punctuated his dreamy account with the usual sobering report: “Three Americans who were captured were badly beaten with two-by-twos. Seems some doubt if they were the prisoners who escaped from here. Ate fish heads and rice for supper. Sliced cucumbers twice today. Hope we don’t get amoebic dysentery from them.”

Comstock maintained reasonable health, other than spells of digestive distress, a severe case of cellulitis on his chin and a two-day bout of dengue fever. His frame, 195 pounds when the war broke out, whittled down to 145 pounds—“my weight during puberty,” he noted.

Still, everyone imprisoned required deep reserves of resilience, lest their days be numbered. Comstock summoned the strength to continue on. Every day, he wrote on slips of rice paper or, if it had been a week bolstered by a rare delivery of an 8-pound Red Cross POW box (chocolate, cheese, cigarettes, corned beef and coffee being among the prized contents), the white expanse of a packaging label.

“What he did by having the diary, having his routine, by reading, by playing chess, carving little chess pieces, by playing volleyball, I think he was really distracting himself,” said Steven Oboler, MD, who was POW physician coordinator at the Denver VA Medical Center and Comstock’s physician in the 1980s. “He was allowing himself to be able to function – and thereby help save the lives of hundreds of POWs—over a much longer period of time. I think I would have been dead. I don’t think I would have survived.”

A great portion of the diary, which in original form is a small mountain of hand-scrawled notes (130 pages typewritten), is devoted to chronicling rumors—some of them fact, most not—that swirled incessantly in the tropical air.

“I really think that’s one of the things that keeps people who are imprisoned, incarcerated, interned alive,” Oboler said. “You go after every rumor.”

“It’s amazing how he has these documented. The war in Europe ended at Christmas ’43, and so many (of the rumors) were way off the mark, and he realized it, but he recorded it,” Oboler added. “And this is one of the unique things about the diary … you can’t go back from a recollection and recreate rumors—you just can’t do it—because you know how it turned out.”

Wittemyer recalled a book authored by a Holocaust survivor who had been in a concentration camp. The author described how it was the people “who had something yet to accomplish” who proved more likely to survive. “I would imagine that for Uncle Doc at that time, his medical career really meant a great deal to him and that he would have been partly living for the people he was taking care of,” she said. “But (he was also living) in anticipation of things he still had to do, and that would have contributed to his will to survive.”

Jacquie Kilburn said it was startling to read about all the things Uncle Doc and the prisoners ate. “One time he wrote about one small dog for 300 people. Electrocuted on the fence—that was dinner. They stopped taking the worms out of the cornmeal because it was protein.”

Jim Kilburn, another of Comstock’s relatives in Boulder, recalls a humorous entry in Uncle Doc’s POW diary.

The doctor talks of rooting through the worms in his rice rations. Normally, the prisoners ate the worms for the added protein. Occasionally, as he was about to munch on a squirmy invader, Comstock, who possessed a healthy sense of humor, took note of a worm’s “pleading eyes.”

He would toss those aside.

While not particularly profound at the time, the entry hinted at Comstock’s compassionate side in the face of utter brutality. The anecdote underscores the capricious nature of the times. War is filled with death one moment and random deliverance the next.

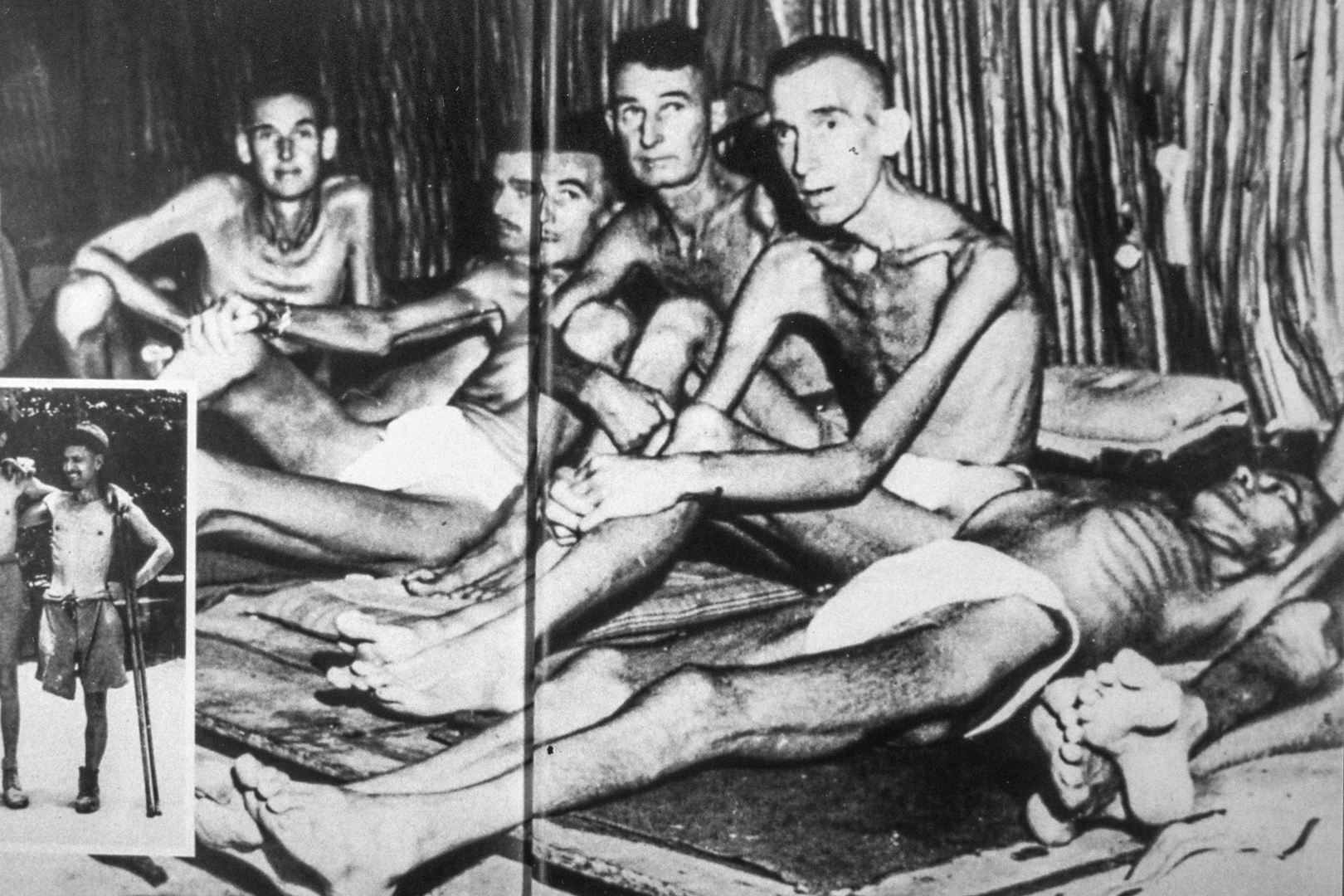

A camp doctor (not Jack Comstock) at a POW camp in the Philippines during the Second World War.

In a Sept. 28, 1942, entry, Comstock noted that two Navy colonels and a commander tried to escape Cabanatuan but were captured by an American guard. After the men “delivered a tirade at Col. Sey, (the medical detachment commander), the three escapees were turned over to the Japanese. They were pretty well beat up and then tied to the fence by the road… The men were stripped except for their shorts. Probably none will live.”

This notation gave Oboler pause. Americans turning their own over to the enemy for brutal beatings and likely execution?

“His description of that is almost like Hemingway. It’s just very, very sparse, but it documents it,” Oboler said. “They turned the escapees in to the Japanese. When I asked about that (entry), he said, ‘We were saving lives. They told us if anyone escaped that they would stop supplying medication. So it was a choice between those few escapees versus hundreds.’

“These were tough choices,” Oboler said.

Hell Ships and Twists of Fate

Japan required an enormous number of workers and huge amounts of oil and raw materials to wage war against the Allies in World War II. The labor force was largely prisoners of war, ferried to mainland labor camps by “hell ships.” The Japanese vessels were left unmarked and, as such, drew fire from Allied forces. In all, 25 unmarked ships transporting Allied and American POWs were verified as having been sunk. Of 18,901 men transported, 10,853 died due to submarine and air attacks.

Among the vessels sunk by Allied forces was the Oryoku Maru. Scheduled to be aboard the transport, along with a labor detail of 500 men, was Jack Arthur Comstock, MD, of Boulder.

In May 1942, near the end of his second month as a prisoner, the doctor from Boulder was part of a detachment bound for Cabanatuan, where the medical officers would spend the bulk of their time in captivity. The group spent a couple days at Bilibid Prison before continuing the trek north.

“Washed my clothes today. Held sick call from 1 to 4 p.m. for entire prison camp,” Comstock logged on May 28 of that year. “Am cutting possessions to very minimum and eating canned food as fast as possible to decrease carrying load. Rumor we will move again tomorrow. Never thought I would be a jailbird in Bilibid Prison. Wish war would end soon.”

Fast forward two-and-a-half years to October 1944.

In the homestretch of his POW ordeal, Comstock would complete one of those full circles that curiously happen in life. He returned to Bilibid Prison as part of a medical detachment for a detail of about 500 American POW slave laborers. From there, Comstock was scheduled to board the Oryoku Maru along with the laborer troops and head north to slave camps in Japan.

The ill-fated Oryoku Maru became “one of the most famous hell ships in existence,” said Steven Oboler, MD, Oboler soaked up the stories of ex-POW patients who survived various wars, including the Southwest Pacific Theater of WWII.

“The Japanese were brutal,” he said. “They didn’t respect the Americans for surrendering, but they didn’t want to kill them. They needed laborers, so they wanted to keep (the prisoners) functional because they needed the laborers.”

Because hell ships were of particular interest to Oboler, the doctor zeroed in on Comstock’s diary entries about a ship transport to mainland Japan.

“He was reassigned at the last minute,” he said of Uncle Doc. “He was at Bilibid with his detail and was going to get on the ship. And then he was reassigned to go to a local hospital – Sakura Hospital – near Fort McKinley with an 80-man detail.”

Unexpected deliverance to Sakura Hospital. The fortunes of war. Such as they are.

“He only talks about it a couple of times (later in his diary), about how lucky he was,” Oboler said. “It turns out that 25 POW ships were sunk. The Japanese refused to mark them either as POW ships or with Red Crosses, so American submarines and air crew had no idea that they were doing anything except transporting (Japanese) military equipment and supplies.

“Your chance of making it to Japan, Manchuria, or Hermosa to work as a slave laborer was less than 50%,” Oboler added. “Dr. Comstock would not have known that. It was only ‘til the end, after he got back to Bilibid, that he learned about what happened to the Oryoku Maru.”

The Japan-bound ship carrying 1,600 Americans (including the 500 who were to be under Comstock’s medical care) was bombed by Allied forces shortly after departing Manila, sinking in the shallows of Subic Bay, just off Alava Pier, on the northwest coast of the Bataan Peninsula. The prisoners who survived the blast attempted to swim 300 yards to shore.

Those who survived “were kept on tennis courts with no water for days,” Oboler said. “If they strayed off, they were machine-gunned. They then were loaded onto two other hell ships, and both of those had horrible fates. So, it was just by luck (Comstock wasn’t aboard), and he never quite understood why.”

Another Glimmer of Hope

Just a month after averting peril aboard the Oryoku Maru, Comstock spent Dec. 7, 1944, the third anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, at Camp Sakura listening for bombs being dropped by American planes.

Just the day before, he watched several Japanese planes wheel in the sky and drop to earth in kamikaze formation.

“Very quiet today as far as we are concerned. …,” he wrote. “Face (from cellulitis) is improving. Am now using Watkin’s antiseptic. Dad would be very interested. More mail today, but none for me. Got a table in our quarters. Makes eating more pleasant. Am sleeping very poorly. Very unusual. Am losing weight rapidly. Sure wish Yanks would come.”

In fall 1944, Comstock, was assigned to travel to Bilibid Prison in Manila then to a boat along with 500 slave laborers bound for Japan. With the medical detachment approaching, he knew the time had come.

He needed to stash the latest collection of his journal entries underground—literally.

As he’d done throughout his captivity, Comstock stowed a pile of gum-wrapper-sized scraps on which he’d been writing into a bottle and buried it in the sandy ground at camp Cabanatuan. “He couldn’t tell me what the jar was, but it sounded like a big mustard jar,” said Steven Oboler.

By surprise twist, Comstock—and his diary—survived.

Set Free: Down Goes the Rising Sun

The squadron of distant specks-turned American planes that Comstock spied on the horizon in September 1944 ignited a glimmer of hope. Indeed, the spectacle presaged a turn in the war. By early February 1945, Allied forces had retaken Luzon in the Philippines.

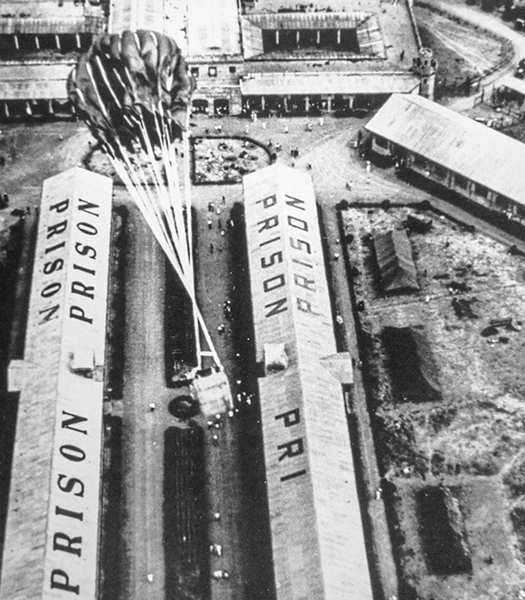

On February 4, 1945, Comstock, who by this time had been transferred from Fort McKinley back to Bilibid Prison, wrote, “Americans knocked open a door in Bilibid wall at 7 p.m., but could not come in because of bars. … They were part of advance units. What a wonderful sight to see free Americans. … Many fires burning … sky dark with smoke. Sun very red and dim behind the smoke as it set. It all looked like the rising sun of Japan was setting tonight.”

Then on the morning of Feb. 5, he described the moment of being set free by the U.S. Army Rangers: “Americans have moved into the compound with machine guns, rifles, etc. … It is impossible to describe how happy we all are. Got to send a radiogram home. Wonderful! Just to see these soldiers in their green uniforms … all well-nourished and looking plenty tough.”

Bilibid Prison was about seventy miles south of Cabanatuan, the scene of the dramatic liberation recounted in Hampton Sides’ best-selling book, “Ghost Soldiers: The Epic Account of World War II’s Greatest Rescue Mission.”

After the liberations, Gen. MacArthur gave all American POWs captured in the Philippines thirty-day leaves to retrieve personal belongings. Two weeks after liberation from Bilibid, on Feb. 16, 1945, Comstock was driven back to his prison camp outside of Cabanatuan by an Army Intelligence officer:

“Was a long, hot, dusty trip, but worthwhile,” the doctor wrote. “I got my diary and personal papers… Also got other personal records of other officers… Camp was a mess… Thoroughly looted and looked very dilapidated.”

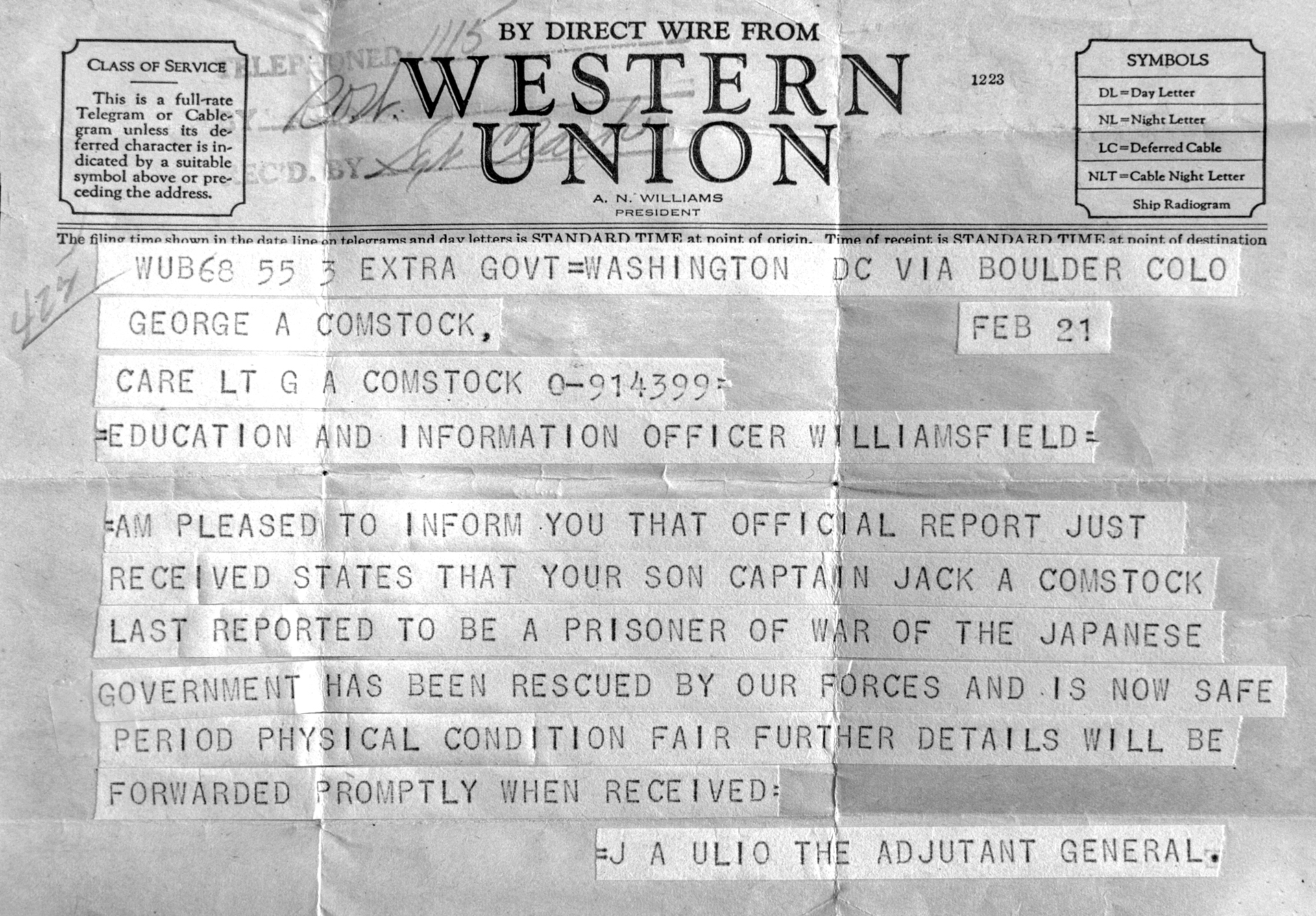

He remained at Luzon for a short time after the rescue. He closed the nightmare of his South Pacific years with this dispatch, on American Red Cross stationary and dated Feb. 8, 1945, Philippine Islands: “Dear Mama and Dad: It would be impossible to describe how happy I am. To be free again and back under the American flag is something that only a prisoner of war, especially of the Japanese, can really appreciate.”

Back in the States at last, Comstock continued his medical career in the newly created U.S. Air Force (Strategic Air Command), including a stint as post surgeon at the Roswell, N.M., Air Force Base. He was a medical observer at the first hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1947. Comstock contracted ocular histoplasmosis while stationed in the Midwest and began to lose his vision late in his career. He became the personal physician to General Curtis LeMay and retired as a full colonel from the Air Force in 1957.

Uncle Doc returned to Boulder where he cared for his parents and other family members. He became revered in his neighborhood for masterful gardening and culinary skills including the popular “Comstock float”—an ice cream-and-soda treat—until his death at age 81 in 1996 from complications from Parkinson’s.

Retirement was a satisfying and family-centered period of life for the decorated veteran. However, he remained reticent about his experience as a POW.

“He raised flowers in the garden. He rode his bike because he couldn’t drive; he was legally blind,” said Nancy Wittemyer, one of Comstock’s nieces. “He had an extensive collection of classical music records and a wall full of good literature. He took care of I don’t know how many people, because I think he felt gratitude.”

Jacquie Kilburn, another niece who lives in Boulder, isn’t sure what prompted her uncle’s reticence about his war days. While acknowledging that survivor’s guilt can manifest in people in the wake of traumatic events, Jacquie never noticed Uncle Doc struggling with feelings of guilt related to his POW experience.

“I just saw him making the decision to make the most out of life,” she said. “His food … the flowers, and just helping other people. I think he just wanted to move on for the most part.”

It was more self-consciousness than guilt that kept Comstock from wanting to publicly share his diary, which at one point he had an Air Force secretary transcribe into 130 typewritten pages. When Comstock broached his POW journal during an appointment with Oboler in the 1980s, the history-buff doctor was instantly intrigued. At first, the doctor said, it was “like pulling teeth to get him to talk about his military and POW experience.”

Jim Kilburn, Jacquie’s husband, said it was interesting to see Comstock’s view of the diary gradually soften over the years. “There were certain passages where he named somebody and said something (disparaging), and he was afraid that would get out later on,” Jim said. “Dr. Oboler was like, ‘Man, it’s been 50 years …’”

Finally, on Nov. 12, 1987, Comstock allowed the diary to go public. He agreed to have the original hand-scrawled notations be housed at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. His permission note was succinct: “I hope the information here will be of interest and of value. Jack A. Comstock.”

Oboler, long fascinated by the courage of POWs in the face of unfathomable circumstances, is familiar with the Department of Veteran Affairs list of conditions—depression, coronary artery disease, hypertension, psychosis, anxiety disorders—that are prevalent among ex-POWs.

“It’s like first responders—the trained people on an accident scene. They see it, there’s blood, there’s gore, but they kind of turn that part of themselves off,” he said. “That’s why later we look for post-traumatic stress disorder, guilt feelings, nightmares, anxiety disorders, depression.”

Possibly, the act of recording daily events was Comstock’s way of processing the moments within the larger story of war, a way of sharing events as he saw them.

As Oboler observed, Comstock made no mention of faith nor belief in God anywhere in his diary. But he often wrote of hope, and he frequently mused about family and home.

Psychologically speaking, the VA physician said, Comstock “did remarkably well” in his post-military life. Oboler recalled a conversation in which the retired colonel expressed sadness about those who perished aboard the Oryoku Maru and not being there to help the wounded in the tragedy. Comstock occasionally mentioned feelings of guilt about not being able to give POW patients more of his food, Oboler said, but he acknowledged that “if he were to get sick, it would ill-serve everybody in the camp.”

A Storyteller, a Hero

Perhaps it was in quiet, undisturbed spaces where Comstock reflected on his POW experience. How did he survive those endless days, weeks and months on the hot, sandy doorstep of despair, disease and death? Was it the click of a pen or stubby pencil and scribbles on scraps of paper – done at grave risk – that ultimately saved him?

“He knew he had a function (as a storyteller), so he documented these things but didn’t dwell on them,” Oboler said. “As MacArthur said: ‘Son, these are the fortunes of war.’”

Melissa De Santis, MLIS, AHIP, director of the Strauss Health Sciences Library at CU Anschutz, where a digital copy of Comstock’s POW diary is housed, said the journal’s profundity comes through its perspective. Many historical accounts, especially those of war, get filtered through the perspective of leaders – the commanders in the field making the decisions.

“The reason this document is so important is that it is a personal story,” De Santis said, “and it gives us a glimpse of the day-to-day life of a prisoner.”

Most likely, the humble doctor from Boulder would’ve eschewed any superlatives attached to his character. Oboler, however, wrote in a prelude to the digital diary that Comstock was a “quiet hero to me… He not only survived, but his selfless actions—including being able to get the weakest men under his care an extra egg or banana – helped hundreds of others to survive.”

Comstock’s diary underscores the power of hope amid the most desperate of times, and it cemented a friendship between a Denver doctor-turned-war buff and a Boulder doctor-turned-Bronze Star winner.

Oboler shared with Comstock what another famous prisoner of war—and Hemingway-esque diarist Winston Churchill —wrote about his own experience: “It is a melancholy state. You are in the power of the enemy… You must obey his orders, await his pleasure, possess your soul in patience. The days are very long; hours crawl by like paralytic centipedes.”

Although Uncle Doc’s vision was failing, his eyes lighted up. “He absolutely loved it,” Oboler recalled. “He said he could completely relate.”