Story

Early History of Bent County

This article, written in the 1940s by the daughter of Amache Prowers, provide a unique view of early Colorado history from a woman of mixed Indigenous and Anglo-American ancestry.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Colorado Magazine, we’ve selected some of our best articles from the last hundred years to republish online. This article was originally published in the November 1945 edition, and has been reproduced here as it was originally published. Some additional photos have been added.

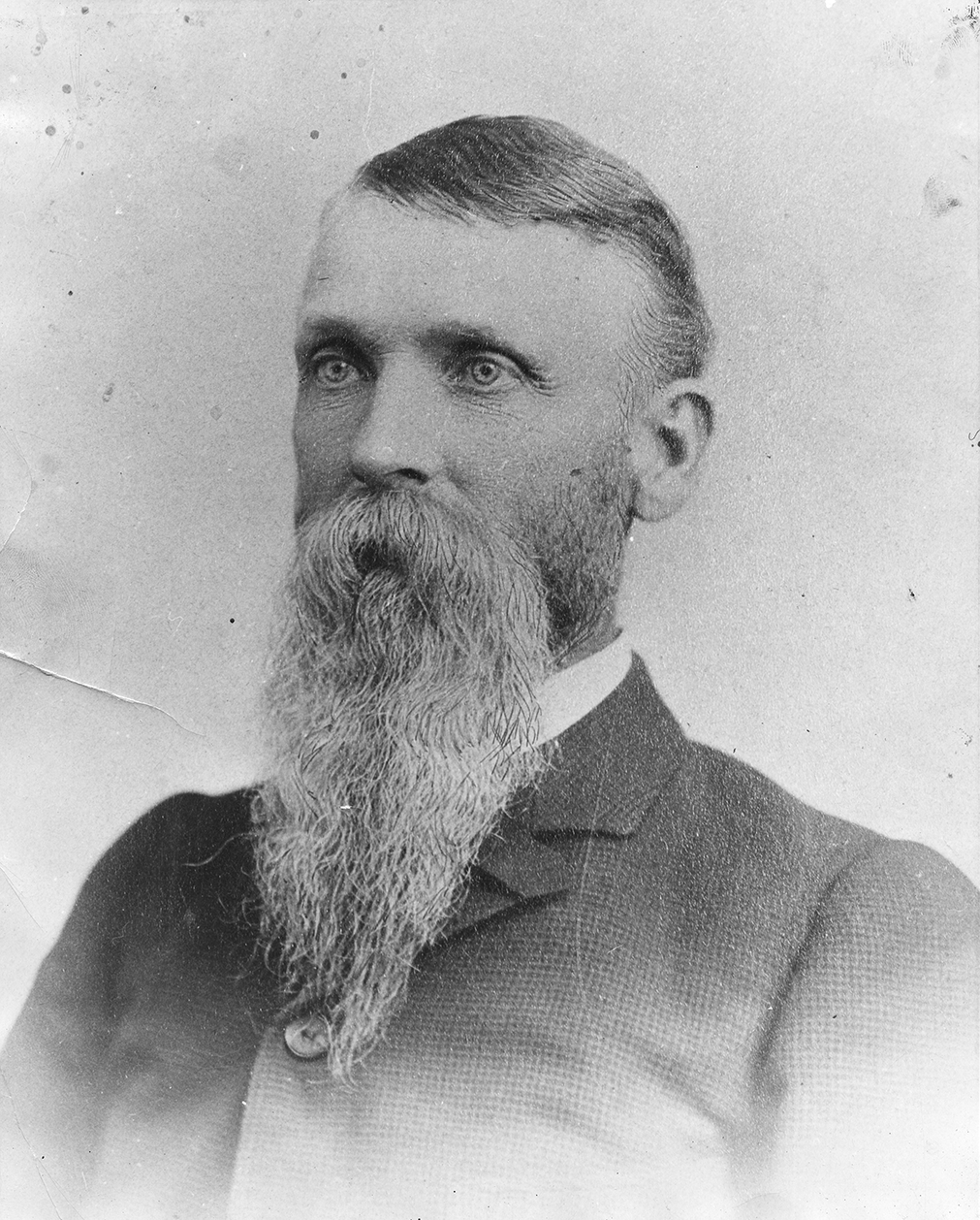

My father, John Wesley Prowers, was born near Westport, Jackson County, Missouri, January 29, 1838. His boyhood was not a happy one. When he was quite young his mother married a second time. John Vogil was not kind to his small step-son and gave him few advantages. Father’s formal education ended with just thirteen months in the public schools.

In 1856, at the age of eighteen, he accepted a position with Robert Miller, Indian agent for the tribes of the Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches, Cheyennes and Arapahoes of the upper Arkansas region. Together they set out from Westport, Missouri, with a wagon train loaded with annuity goods, Bent’s new fort being their destination.

Upon their safe arrival at that place, Agent Miller sent out word for the Indians to come into the Commissary to receive their portion of the annuity goods. For a period of fully two months father passed out sugar, bacon, cornmeal, oatmeal, salt, beans, coffee, clothing and numerous other articles to the Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and other tribes who came to the fort.

For father, young and newly come from the East, the excitement and romance of the life at Bent’s Fort held a great fascination. He watched as the covered wagon trains on the Santa Fe Trail stopped at the fort to have an ox shod, or a wheel tire welded; he saw bearded trappers from the mountains, in fringed buckskin suits, bringing in their winter’s trapping of beaver skins; sometimes Mexican men in wide sombreros and vivid sashes rode in bringing the romance of the land to the south, or an occasional French-Canadian stopped for the night with tales to tell of a mysterious north-land. More often bands of Cheyennes or Arapahoes rode in from the plains, on their wiry Indian ponies, bringing buffalo robes to trade for white man’s goods; perhaps, most of all, he noticed the shy glances of dark-eyed Indian maidens in beaded deer-skin. Whatever it was, father decided not to return to Missouri, but to make this country his home.

So, as soon as his work with Miller was finished, he accepted a position with Col. William Bent, Indian trader at the fort, and remained in his employ for seven years. During this time, he was continuously on the trail, in charge of wagon trains, freighting in supplies from the trading posts on the Missouri to those west. He made in all twenty-two trips across the plains. Occasionally his western terminal was Fort Union, sometimes Fort Laramie, more often Bent’s New Fort on the Arkansas. Twelve of these trips were made on his own initiative, and in each case he realized a goodly profit from the trade goods he freighted in. After five years these trips became mere routine to father, but in 1861 the return trip to Fort Bent took on new significance for him. The moment he entered the adobe walls of the fort he glanced eagerly around to see if a certain pair of dark eyes had noted his return, for father was in love with a little Indian princess, Amache Ochinee. Amache (father shortened her name to Amy) was the daughter of Ochinee, a sub-chief of the Southern Cheyennes, called One-eye by the white people. With her father’s consent, Amache married my father, John W. Prowers, near Camp Supply in Indian Territory, in the year 1861. She was fifteen years of age. They started housekeeping in the commissary building at New Fort Bent.

In the winter of 1862 when father made his usual trip to Westport he took his young bride east with him and when he returned to the fort she remained behind with father’s aunt. Here at Westport, Missouri, on July 18, 1863, I was born. My young Indian mother named me Mary. For the next three months she anxiously watched the Santa Fe Trail to the westward, longing for the return of my father with the wagon train so that she might go back to the prairies and the life she loved.

My first home in Colorado was on the cattle ranch that father had established in the big timber on Caddoa Creek. I was five months old when I arrived here, as it took us two months to make the trip home by ox-wagon. There were three large stone buildings on the ranch at Caddoa when father took mother and me there to live. In 1862 when a band of Indians, the Caddos, were compelled to leave Texas because of their fidelity to the Union, the U.S. Government undertook to locate them on the Arkansas. General Wright selected a site at the mouth of the creek still known as Caddoa, and had three large stone buildings erected. The Caddos came up and inspected the place and decided not to accept it. So preparations for their occupancy were abandoned. In 1863 father decided to purchase it as a ranch from which to herd cattle and to furnish supplies to the troops coming through.

As father made his trips back and forth with the wagon trains, he used to gaze out over the vast acres of grassy prairies and picture grazing there, not buffalo, but great herds of cattle all bearing his brand. He saw the possibilities in the cattle business in this open range and dreamed of being a cattle king. Then he set out to make these dreams a reality. In 1861 he took his savings east with him and purchased from John Ferrill of Missouri, a herd of 100 cows. These he brought in and turned out to graze on the range from the mouth of the Purgatoire to Caddoa. Then in 1862, for $234, he purchased a good bull to run with the herd. From that time on father tried continually to build up his herds, weeding out the original Short-horn strain and replacing them with Herefords, as they seemed to stand the cold winters much better than the Short-horns.

During the winter of 1864 and 1965 we were often at Fort Lyon, where father had charge of the Sutler store and acted as interpreter for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians at the post, part of the time being regularly employed by the commanding officer, sometimes acting voluntarily. He was also government contractor and employee.

In the middle of November, 1864, we were at the ranch on the Caddoa where father was herding government beef cattle, horses, and mules. The white settlements on the Arkansas river at the time were few and isolated; they were Colonel Boone’s, eighty miles west of Fort Lyon; the stage station at Bent's Old Fort; Moore and Bent at the mouth of the Purgatoire; father’s ranch at the mouth of the Caddoa and Fort Lyon. Relations between the plains Indians and the white people were growing more and more strained ; the chiefs of the Arapahoes and the Cheyennes, puzzled by the ways and the many words of the white people, often came to father for explanation and advice. At this time Chief Black Kettle and Grandfather Chief One-Eye told father that Black Kettle had been to Denver, where he talked with the big white chief Governor Evans, and with Col. Chivington; that they could not make any treaty with them but had been told that they must deal with Major Wynkoop, then in charge of Fort Lyon. They said that they had returned all the white prisoners they had held and were ready to do anything Major Wynkoop asked. He had told them to bring in their families and lodges and they were now going out to do his bidding. Father told them to camp near us on the Caddoa and that he would accompany them to the fort as interpreter if they wished to hold council. One-Eye, my Grandfather, at once brought in his family and lodges and camped near the ranch. Black Kettle left his family and lodges camped on Sand Creek, but brought in a number of his sub-chiefs with him; father and Ochinee accompanied the band of chiefs into Fort Lyon. They found that Major Wynkoop had been relieved of his command and that Major Anthony was in charge.

Major Anthony promised them that he would do all in his power to bring about a permanent peace; in the meantime they were to go back to their camp on Sand Creek and let their young men go buffalo hunting, as he could not issue them any provisions until further government orders came from Leavenworth. He then said he could not keep them at the fort for the night. Father asked that they be allowed to come to our place. They remained camped near us for two nights; they said they were sorry that Major Wynkoop had been relieved but believed that Major Anthony would do all he could for them. Father assured them that everything looked favorable, gave them presents of sugar, coffee, flour, rice and bacon, and tobacco bought for them and sent out by the officers of Fort Lyon. Major Anthony had agreed to come out to father’s place for another council with them. He did not come but sent out the Fort interpreter, John Smith, to talk with them, who said that Anthony had sent word for them to go back to their lodges on Sand Creek and remain there for they would be perfectly safe. Father shook hands all around and the Indians left for their camps on Sand Creek. That was the last any of us saw of my Grandfather, Chief One-Eye.

One Sunday evening, the last week in November, about sundown, the men of company E of the first Colorado Cavalry, by orders of Col. Chivinton, stopped at our ranch on the Caddo, disarmed father and his seven cow-hands, and held them prisoners, not allowing them to leave the house for two days and nights. At the end of that time Captain Cook ordered that he be released. No explanation was offered as to the cause of his arrest, but in light of later happenings we thought it was due to the fact that father had an Indian family, and might communicate some news to the Indians on Sand Creek.

On Nov. 29, 1864, in the early dawn, Col. Chivington and his men fell upon my mother’s people camped on Sand Creek, with the American flag and a white flag flying over Chief Black Kettle’s tepee. Grandfather Ochinee (One-Eye) escaped from the camp, but seeing that all his people were to be slaughtered, he deliberately chose to go back into the one-sided battle and die with them rather than survive them alone. The Southern Cheyennes would have been completely wiped out as a tribe had it not been that a small band of them had left camp the morning before and had gone up the creek on a hunting trip to obtain meat for the Indians, who had been issued no government supplies for several weeks. Grandmother was not killed, as she and the wives of some of the other chiefs had been detained at Fort Lyon, as hostages, that the Cheyennes and Arapahoes would keep peace. Mother, Father and I were out at Big Timbers when we heard of the massacre. We immediately hurried to Fort Lyon to be with Grandmother, and to be of what help we could to the stricken Cheyennes. Father was called by the government to testify at the investigation held at Fort Lyon. He told his story there as he often, in later years, told it to us children and as I have given it here. Mother was always very bitter about the Sand Creek Massacre. A number of years later, while she was attending a meeting of the Eastern Star in Denver, a friend brought Chivington over to introduce him to mother, saying, “Mrs. Prowers, do you know Colonel Chivington?” My mother drew herself up with that stately dignity, peculiar to her people, and ignoring the outstretched hand, remarked in perfect English, audible to all in the room, “Know Col. Chivington? I should. He was my father’s murderer!”

Whether Col. Chivinton’s act was justified or not still is a subject for controversy among students of Colorado history. At any rate, the U.S. government tried to make reparation to the Indians; the treaty of 1865 stated that each person of the Indian band who lost a parent or was made a widow upon that occasion should receive 160 acres of land. They could choose this land wherever they wished from their reservation in the Arkansas Valley. Naturally they chose the best hay land along the river bottom. Father acquired much of his cattle range in this manner; of course grandmother and mother each received this land grant from the government. Then father bought out the claims of other Indians. Julia Bent, a daughter of George Bent by a Cheyenne wife, received the 160 acres which surrounded Fort Lyon. Father bought this quarter section from her to enlarge his range.

In 1868 Father moved his family to Boggsville, a small settlement about two miles south of the present city of Las Animas. Thomas O. Boggs, for whom the place was named, had returned from New Mexico in 1866 with L. A. Allen and his brother-in-law, Charles L. Rite. He started improvements on his ranch at once. Both Thomas Boggs and Kit Carson were thrown out of employment when the trade in buffalo robes at Bent’s Fort was broken up. Kit Carson moved from Fort Garland to Boggsville in 1867. He had obtained title, through his friend Ceran St. Vrain, to two ranches on the Purgatoire, the first about a mile south of Boggsville and the other at the end of Nine Mile Bottom. He made some improvements on these ranches, but settled at Boggsville in a house belonging to Thomas Boggs. These two friends went into the sheep business together, using as range their combined ranch lands. They always seemed to me more like brothers than partners.

Father built a fourteen-room adobe house; our family was increasing with the years. In all, there were nine of us Prowers children. I was the eldest, then Susan (who died in infancy), Kathrine, Inez, John, Jr., Frank, Leona, Ida, and Amy. Our old home, and that of Thomas O. Boggs are both still standing at Boggsville (1945).

Some of the neighboring ranch families were: R. M. Moore, Col. Wm. Bent, E. R. Sizer, Urial Higbee, Luke Cahill and C. L. Rite.

After father had his home built, and mother, I, and my two small sisters comfortably settled, he started the first irrigation project in the county. Thomas Boggs, Robert Bent, son of Col. William Bent, and he dug a large irrigation ditch, under which farming was started at Boggsville and at the Bent place. Over 1,000 acres were put under cultivation. It proved a very profitable enterprise for prices were high: Corn 8 to 12 cents per pound, flour $8 to $12 per hundred and potatoes at 25 cents per pound.

In February 1870, by a legislative enactment, Bent county was organized. Las Animas was designated as the County seat. The first election was held on Doctor Sizer’s ranch, seven miles south of the present site of Las Animas, on the Purgatoire River, during the first week in November, 1870. Father was elected County Commissioner; John M. Boggs, County Clerk; Bob Baker, County Assessor; Josiah Russell, Probate Judge; Thomas Boggs, Sheriff; C. L. Rite, Justice of Peace; and Henry Rule, Constable. These were the first officials of Bent County. And the County Seat was changed to Boggsville at this election. Our little settlement now became an important business center. Father opened a large general store and a Post Office was established here.

While engaging in all these other activities, my father’s primary interest remained in cattle. In 1871 he bought “Gentle the Twelfth” of Frederick William Stone of Guelph, Canada. From this time on he set about systematically improving and enlarging his herds and acquiring larger range. During father’s lifetime he fenced 80,000 acres of land in one body and owned forty miles of river front on both sides of the Arkansas river, controlling 400,000 acres of land.

In the fall of 1871 father shipped in eight dozen prairie chickens and turned them loose on our ranch, as an experiment. Judge M. Robinson and Luke Cahill tried the same experiment, turning loose sixteen dozen Bob White quail at the mouth of the Purgatoire. In two years all the prairie chickens had disappeared, but the quail had thrived and increased; there are still many in the county. Hoping to increase the wild game in our county, in 1880 father had two bucks and three does, white-tail deer, shipped in and turned at large near Prowers Station Ranch. This species is still to be found along the Arkansas River, on Fisher’s Mountain, near Trinidad, and on south into New Mexico.

There were now so many little folks among the population at Boggsville, that the crying need was a school. When I was six years old, father sent me to Trinidad to live with my Uncle, John Hough, and attend school there. For three years I attended the school conducted by Rev. E. J. Rice, known as the Rice Institute.

The first school in Bent County was a private or subscription school, opened in the fall of 1869 by Miss Mattie Smith, who later became Mrs. John M. Boggs. In 1870 a school district was organized, with R. M. Moore as President, C. L. Rite, as Secretary, and father as Treasurer. In September, 1871, the first school house was completed, a one-room adobe building, and Mr. P. G. Scott was elected as teacher for the next two years. School opened with fifteen pupils. I do not remember the names of all of them; there were my two sisters, Kathrine and Inez Prowers, Bent, George, and Ada Moore, Charlie and Theresina Carson, and Laura Rite, some Mexican children and one colored child.

I look back with pleasure to these years on the ranch at Boggsville. Mother was a quiet, sweet woman, and very intelligent. She readily picked up the English language. She never talked the Cheyenne language at home, only occasionally with her own people. The Cheyennes were often at the ranch and grandmother spent a great deal of time with us. She told us the story of how Chief Ochinee lost his eye, one day in a game of sling-shot. She tried patiently to teach me the Cheyenne language but I never progressed beyond a vocabulary of five or six words. She would shrug her shoulders in disgust and say, “Oh, you too dumb learn Cheyenne talk.”

Father was always exceptionally good to mother’s people, and they all loved and honored him, paying heed to his advice as to their relations with the white people. The Cheyennes were always welcome at the ranch; father saw that they were well treated and that they had a good present to take along when they returned to the tribe. Many a time I have seen father send out a rider on the range to select a riding horse for one of mother’s relatives. Often a band of Indians returning from the hunt, would ride up to the ranch carrying their bows and arrows and ask father to send out a team and wagon to bring in the game they had killed.

Mother clung to many of the Indian customs and we children learned to like them. At Christmas she always prepared us an Indian confection made thus: She would slice dried buffalo meat very thin, then sprinkle it generously with sugar and cinnamon and roll it up like a jelly-roll. Then on Christmas day she would cut slices from the roll and pass it around; this was our Christmas candy. We kids just loved it, but father looked on rather askance, and would slip over to the store to return with a wooden pail of bright colored Christmas candies for us. Every season mother used to gather prickly pears for sweet pickles. She would burn off the stickers, and cook up the pears in vinegar and sugar. They were delicious. She knew all the prairie herbs and their use by the Indians; she gathered mint to make medicine; sage leaves were dried and steeped into sage-tea which she felt was just good for everything. We always had preserves made with the wild plum, choke-cherries, grapes, etc. And of course we had our spring greens of lambs-quarters (Chevopadium album) and wild lettuce (Lactuca seariola).

I loved to go to the Indian camp with grandmother. She showed me how the Cheyennes caught the dry land turtles, roasted them in the oven until the shells popped open, and then scooped out the delicious white meat and ate it. It seemed to me that the Cheyennes ate almost everything. They killed for food the jack-rabbit and used the skins for clothing, they ate buffalo, antelope, deer, elk, prairie-dogs and squirrels. But they never would touch fish. Grandmother lived to be ninety years old but she never succeeded in teaching me the Cheyenne language.

Father often used his popularity with the Indians to protect the white settlers in the Arkansas Valley. From the years 1868 to 1873 the Indians were restive and things went from bad to worse. At first they merely killed a few beef cattle for their camp needs. Then they grew bolder, making frequent raids upon the outlying ranches, killing the herders, running off horses, mules, and cattle. The Sizer ranch was attacked two or three times, the barn burned, and cattle stolen. On election day an attack was made all along the creek. Thomas Kinsey, a judge of election was killed while on his way from Sizer’s ranch to the voting place at Boggsville.

The Bent, Boggs, Carson, and Sizer estates all lost stock, as did my father. The settlers on the Purgatoire gathered for defense at Boggsville, and those in Nine Mile Bottom, at the ranch of Urial Higbee. Father and Thomas Boggs both had adobe houses, and these were considered the only safe kind in case of an Indian attack. Then, too, we had large corrals for the stock and father had a general store where all could obtain supplies. When the body of Thomas Kinsey was found, a general alarm was sent out. All the ranchers hurried their families into Boggsville, there to await developments. A small party of soldiers was sent out from the fort to follow the Indian raiding party; in the skirmish which followed four Indians and two soldiers were killed, twenty-five miles south of the fort. Most of the Indians escaped, taking with them a lot of the stock stolen from Boggsville.

In the fall of 1873 the Kansas Pacific railroad built a branch from Kit Carson to the south side of the Arkansas River, where a new town, West Las Animas, was at once laid out. The Indians resented the coming of the railroad, knowing it meant the end of their way of life. They threatened to wipe out the new little town. A war party of 300 Cheyennes appeared at dusk, silhouetted against the horizon, a long line of horsemen all carrying guns. Father rode out to meet them. He told them how much they meant to mother, for there were her people, he pointed out that he himself had always been good to them, had given them presents and even now, if they would return to the ranch with him, he had good presents for all. Father took them all to the ranch, had a large number of cattle killed, and feasted with the Cheyennes all night. In the morning he took the chief and sub-chiefs to the fort where a peace council was held, thus averting the danger to the new town of West Las Animas.

In the fall of 1873 we moved into the city of West Las Animas; father established the commission house of Prowers and Hough. The town was a mixture of wooden and adobe buildings. Some of the first settlers were: Hunt, a saloon-keeper; William Connor, who moved the American house over from Kit Carson; Hughes Brothers lumber dealers; Shoemaker and Earhart, merchants; and one other commission house, that of Kilberg, Bartels & Co.

I found the activity at the Commission house very fascinating. I liked to see the funny little engines puff in with their loads of freight. Father received these goods from the railroad, paid the freight, hired teams (mostly ox-teams) and shipped the goods on in that way to their destination. What a busy place Las Animas was in those days! There was a large territory to the south which had not yet been penetrated by a railroad. Las Animas was the shipping point for government freight to all their posts in the Southwest, and it was through the two Commission houses here that most of the merchants in southern Colorado, New Mexico, and part of Arizona got their goods. From the south came long wagon trains hauling in hides, pelts, ores and live-stock to the railroad, to be shipped east; they unloaded their wagons and camped on the prairies near town, awaiting their turns to load freight for the south. There were no fences or fields close to town; sometimes the prairie was dotted with freighter’s camps as far as one could see.

Needless to say, father made plenty of money from the commission business. He operated, also, a large retail store in partnership with W. A. Haws. Their clerks knew little Spanish, so father brought in a young man from Trinidad, Philipe Gurule, whose chief and almost only business was to act as interpreter in the store. Many wealthy Mexicans operated freight trains and the English language was an unknown tongue to them.

In 1875 father helped organize the Bent County bank. In 1873 he was elected to represent the county in the Legislature. In 1880 he was again elected to the General Assembly as a representative of Bent County, where he originated and pushed through the bill on apportionment, commonly termed the “Sliding Scale Bill.”

West Las Animas was so called because there was a post office at Las Animas, opposite Fort Lyon and the name West Las Animas held until the Las Animas post office was moved to West Las Animas, which then dropped the West from its name.

In 1875 the county seat was moved from Las Animas City to West Las Animas, where it remained.

In 1873 a printing press was brought to Las Animas city by C. W. Bowman and on May 23, the first issue of the Las Animas Leader was in the mail. Later the paper moved to the new city, West Las Animas, where it is still going to press each week.

My first instruction in religion came with an elderly missionary, named Father Clark, when he came riding up to the ranch house, on a white mule. He wore a long white beard which reached below his waist. He alighted, came in, and announced that he would hold services there that night. So a rider was sent out to all the nearby settlers, A goodly number gathered in our livingroom that night, and I listened open-mouthed to a lurid sermon that I shall never forget. Father Clark was very dramatic and very earnest in his work; he made a regular circuit of our valley, and he never forgot to take up the collection. The cattle-men were all very liberal with him. Although father was not a church member, he always gave generously to resident pastors, no matter what denomination. In 1872-73 Rev. John Stocks of the Methodist church held services at Las Animas, and Rev. E. C. Brooks acted as methodist pastor from 1873-74.

When a four-room brick school was built at West Las Animas in 1875, Mother Amache said that I need not return to Rice’s Institute at Trinidad that fall. I attended school here until I was twelve years old, when father decided I needed to “learn some manners,” so I was sent to Wolfe Hall in Denver for three years. When I entered school in 1875, Rev. John F. Spalding was Rector; Miss Anna Palmer, Principal; Miss M. Corbyn, Assistant Principal; and Lizzie Brown, teacher of music. My cousin, Ida Hough, went with me. There were eighty-five girls in attendance. School began on Sept. 8 and ended in June, with two terms of twenty weeks each. We had three weeks vacation at Christmas and Easter. We paid by the half year; for board, washing, fuel, lights and tuition in English branches, the cost was $175 per term. Music cost $25 more; so it cost father $400 a year to send me to Wolfe Hall. Each of us took with us a Bible and Prayer book, six table napkins and a napkin ring; all these and our clothing must be plainly marked with our name. A record of our conduct was sent to our parents each month, a record of our grades, and whether we were late or absent at class, study, chapel, table or dormitory. We were carefully trained to “improve our manners and cultivate the graces of refined society.” I was happy at Wolfe Hall and made good progress, becoming particularly interested in music.

At the age of 15 years I went to Lexington, Missouri, where I attended Central (now Bethany) College until my graduation in 1879; I majored in music. It was here that I met and fell in love with A. D. Hudnall of Kansas City. In 1880 he came to Las Animas and we were married; father gave us one of the nicest weddings ever staged in Bent County, and we received many beautiful, expensive gifts. We spent the first six months of our married life in Kansas City, Missouri, while Mr. Hudnall closed out his business interests there; then we returned to Las Animas where my husband had charge of father’s dry-goods store for many years. He was chief buyer for the St. Louis, Missouri, stock-yards for six years, then for the Kansas City stock-yards for twenty-seven years.

The “old Prowers house” in Boggsville, Colorado, photographed in October 1957.

We had a nice life together. I really believe people had more real fun in those days than they do now. We were not always dashing about here and there. We had more time for community life, and we had REAL parties. Christmas, the 4th of July, New Years, and Thanksgiving were always the signal for a community party; we held them at the old hall, a block east of the present City Hall. There was always a big dinner, turkey, roast beef, wild meat; the long tables groaned under the load; and we danced until daylight. My husband was always a rather strict churchman; he did not approve of dancing or music. I loved both. I often played for the dances, and then I was young, I just couldn’t help but dance. They were mostly square dances, and lots of fun. He was always cross about it but I let him pout it out. And the Christmas parties! We would have the biggest tree the boys could cart in from the mountains; and the presents were real ones, not ten-cent store stuff but diamond rings, gold watches, and sterling silver tea sets. The cattlemen had money and they really spent it.

In 1882 father built a modern slaughter-house at Las Animas. He bought up the range cattle, killed them, and shipped the meat east, some going as far as New York City.

When the railroad was extended from Kit Carson to La Junta, it ended the forwarding business of Prowers & Hough. Father then devoted his time to his other interests and particularly to his cattle business, which was always his favorite enterprise. He employed lots of riders and cow-hands, mostly Missourians, rarely Mexicans.

His brands were the Box B, and the Bar X. He built up his herds until at the fall round-up of his ranch, the cattle shipment was a matter of train loads, not carloads. Sometimes as high as eight train loads left our ranch for eastern markets. At one time, the fall check-up showed 70,000 cattle bearing father’s brands. It was his day-dreams of 1860 realized now, twenty years later.

On February 14, 1884, at the age of 46 years, father died at the home of his sister, Mrs. Hough, In Kansas City, where he had gone for treatment; he is buried in the Las Animas cemetery. Many years later mother died in Boston; she, too, is buried at las Animas, where a large, beautiful, red-granite monument carved in Scotland, marks the Prowers graves.

In 1889, when a new county was created by the General Assembly, from the eastern part of Bent county, they paid father the honor of naming it Prowers County.

Father never belonged to a church or a lodge and did not believe in them; but he was a devoted husband and father and gave each of his eight children a liberal education. There never was a better woman than my Indian mother, Amache Ochinee Prowers. She was very active in community life and church work, and was a devoted member of the Eastern Star. When the Granada relocation center was formed at the beginning of World War No. 2, it was called “Amache” in honor of my mother.

Kit Carson was a great friend of the Prowers family. He was quiet and reserved; to me he seemed more Spanish than American. He was always good to the Indians; my mother’s people, the Cheyennes, were particular favorites of his. We played with and grew up with the Carson children. Kit Carson died in May, 1868, and his wife preceded him in death by just a few days. They were buried side by side in the garden of C. L. Rite, at Boggsville. The following winter the bodies were taken up and moved to Taos, New Mexico.

Mr. Hudnall and I had three children; our son, Prowers Hudnall, was born in 1882. While Sheriff of Bent County he was stabbed to death by a criminal. Our daughter, Inez, Mrs. Frank Nelson, is living in Las Animas; and our youngest son, Leonard “Chief” Hudnall is now with the Colorado Fish and Game Department in Denver; his proudest boast is that during the three years he attended Carlisle University, he played football with Jim Thorpe, the world’s greatest football player.

My grandchildren are Lee “Dick” Hudnall, leading business man of Las Animas; Mary Ferreti, Robert, Leonard, Jr., Jack, Lee and Wanona Hudnall, and Gail Batten. I have now nine great-grandchildren.

Of the nine Prowers children, only three are still living (1945). I have a sister, Mrs. Ida Hawkins, residing in San Diego, California, and another, Mrs. Inez Comstock, living in Chicago.