Story

Colorado Under the Klan

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, a Denver librarian wrote this expose on a dark and little-known period of Colorado History, when the Ku Klux Klan worked to infiltrate and take over our state's government.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Colorado Magazine, we’ve selected some of our best articles from the last hundred years to republish online. This article was originally published in the Spring 1965 edition, and has been reproduced here as it was originally published.

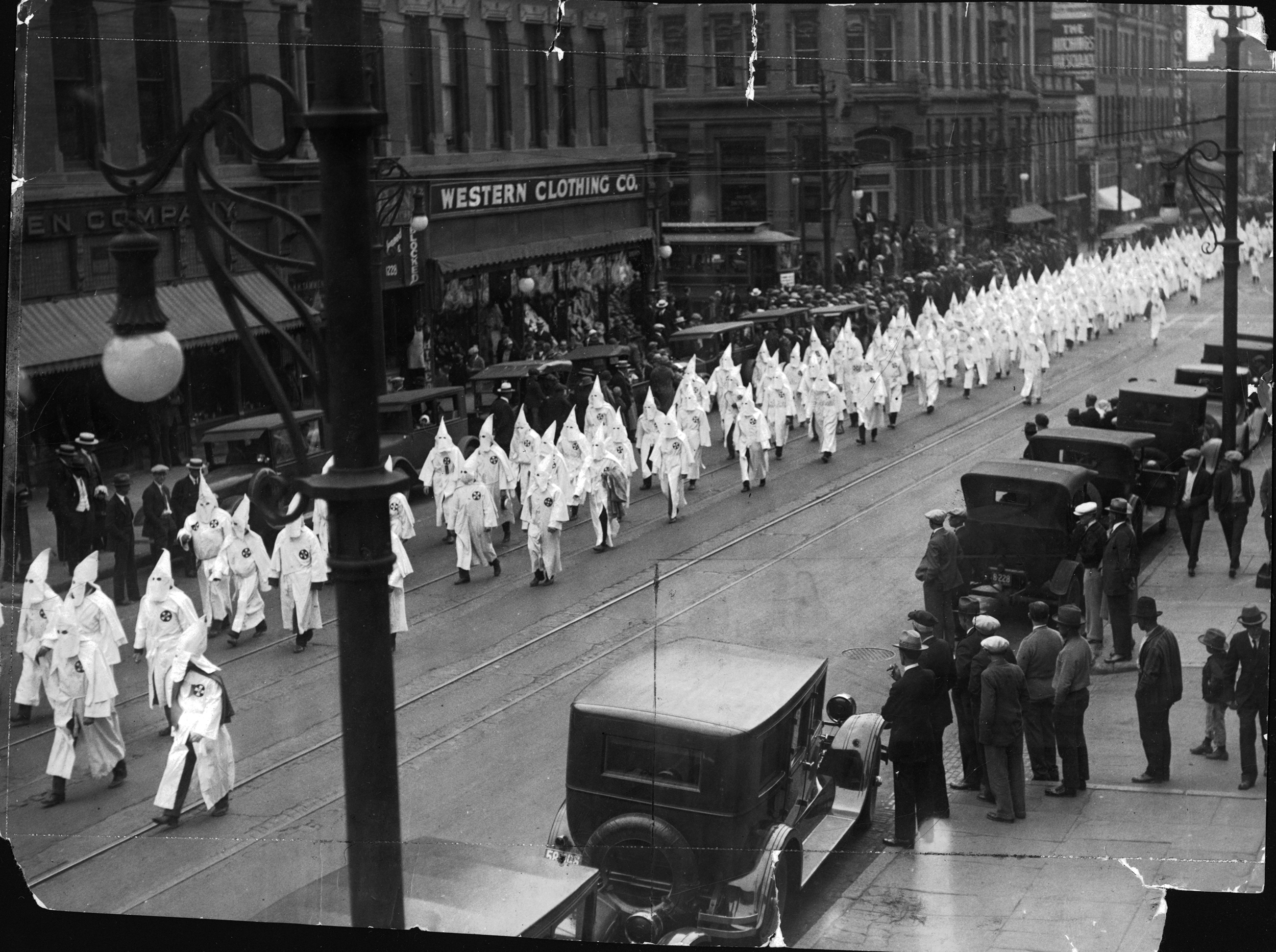

After its establishment in Colorado in 1922, the Ku Klux Klan began–under the leadership of Grand Dragon John Galen Locke–to carry out a program of economic and political control in various towns over the state. The organization made certain that channels for dissemination of propaganda and for recruitment were set up. Then it threatened or coerced individuals, groups, and institutions. Finally came attempts to infiltrate into municipal government with the ultimate goal of complete domination.

The seizure of municipalities was not enough for the Klan; the state government had to be captured also. This was accomplished by obtaining control of the Republican Party, selecting almost all its candidates during the elections of 1924, and making certain the ticket would be successful throughout the state. Once in possession of the executive and legislative branches of Colorado government, the Klan planned to use official acts in furthering its causes on the widest scale possible.

As the year 1925 dawned, Dr. John G. Locke could feel quite pleased with the political situation on the state level. In both the Senate and the House there was a majority of members elected from the Klan-controlled Republican party and he could seemingly count on the passage of any desired legislation. The executive as well as the legislative branch of the government seemed to be in the doctor’s pocket. Governor Clarence Morley could not make a move without first consulting the Grand Dragon. Harry T. Sethman was close to the governor during the first part of his administration because he was thought erroneously to be a Klansman. Mr. Sethman observed that Morley was constantly on the telephone talking to his “master.” If the Governor was too busy to call, his personal secretary would be requested to phone for instructions. One man in the governor’s office had as his primary duty the carrying of written messages between the Capitol and Locke’s Glenarm Place office. For all practical purposes Locke was the governor.

Very soon after his inauguration Governor Morley made a strong effort to secure control of a prized government department for Klan usage. Having in mind Locke’s desire to control enforcement agencies, he tried to remove the Adjutant General of the state militia and replace him with a Klansman. Paul P. Newlon refused to obey the governor’s executive order to resign as Adjutant General and stationed Captain Alphonse P. Ardourel on twenty-four hour duty in his office to prevent the Governor’s appointee from taking over. Furious over Newlon’s defiance, the Governor had the House of Representatives introduce a special bill giving him unquestioned authority to appoint and dismiss the Adjutant General. To give immediate consolation to the disappointed Grand Dragon, Locke was granted a commission that made him a colonel in the National Guard Medical Corps. Dr. Locke thus had an additional uniform to add to the Klan robes which he so delighted in wearing. Another state office was directly given to John G. Locke, when he was appointed a member of the State Board of Medical Examiners.

Such a large crowd wished to attend the new governor’s inauguration that all precedents were broken, and it was held in Denver’s Auditorium rather than in the Capitol. The inaugural message clearly reflected the inspiration of Dr. Locke, although some points that were emphasized had nothing to do with Ku Klux Klan objectives. These were: the establishment of a state reformatory for women, appropriation of funds to carry on negotiations for interstate river treaties, a minimum wage law for women, assistance in revival of the mining industry, elimination of further taxation on gasoline so that capital would be encouraged to develop Colorado’s resources, the setting up of a new highway code for the purpose of preventing waste in construction and maintenance, and the carrying out of the Boulder Dam water conservation project. However, of the other major points in that speech at least four could be related to aims of the Hooded Order. These included the passage of acts excluding certain aliens from residing in the state, eliminating from the prohibition law the right to obtain intoxicating liquors for sacramental use, amending the primary election law so that members of one political party could not participate in the primaries of an opposition party, and abolishing many state boards, bureaus, and commissions.

Ostensible reasons for the latter group of recommendations were: furtherance of the cause of organized labor, providing more jobs for Coloradoans, eliminating abuse of the prohibition law, and saving taxpayers money by removal of useless agencies. Actually, the Klan had ulterior motives: to strike a blow at non-Americans by keeping them out of Colorado, and to attack the Catholic church–without wine the Mass could not be celebrated, and this is the central act of Catholic worship. In addition, the opportunity the democrats had enjoyed in the past primary election to upset the Klan ticket could never occur again. The termination of various state agencies would eliminate jobs held by employees not sympathetic to the Klan. New positions, having similar functions, could then be created and doled out to faithful Klan followers.

The Assembly had been in session for several days, and bills had already been introduced to abolish agencies before the Governor gave his message. The State Industrial Commission was the object of one bill, concerning which the Denver Times observed:

“This action would make the deputy state labor commissioner one of the most powerful officials in the state and would largely increase the number of employed in the office of the Secretary of State whose appointee he is.”

Another resolution introduced in the House would abolish the Civil Service Commission and “throw open jobs of all people employed in the Capitol Office Building and Museum to the winning party at the polls.” The move was also in keeping with a declaration made at a Klan meeting, which stated that the Commission must be eliminated, since “70% of the office holders of the state, protected by Civil Service, were Catholics.” A single man appointed by the governor would substitute for the abolished commission. House Bill 38 would eliminate the juvenile court system, permitting the district court in each county to take over its function. Thus, anti-Klan Judge Ben Lindsey would be once and for all eliminated.

While many developments favored the Morley administration, problems began to emerge which would be of great significance. Four Republican senators stated they would not abide by certain decisions of majority leaders and walked out of the caucus.

These men were Henry Toll, David Elliot, Frank Kelly, and Louis A. Puffer. An effort to placate two of them was made by appointing Puffer chairman of the Finance Committee and Elliott chairman of the State Affairs and Public Lands Committee. Walter W. King and John P. Dickinson, two other dissatisfied senators about to join the above-mentioned insurgents, were given chairmanships of the Rules, Banking, and Reapportionment Committees. The Democrats had decided to block legislation rather than make their own proposals and “play a waiting game, hoping for a split.” Therefore, they could not have been more pleased with the Senate revolt.

The House, overwhelmingly composed of Republicans elected from the Klan-controlled party, continued to cooperate fully with the administration, and the Senate rift was not at first felt. During a long session, which lasted into the late evening of January 21, the Assembly saw to it that the legislation desired by the Governor was introduced before the midnight deadline designated by the law. The majority of the so-called administration bills was introduced in the House. Two bills especially pleasing to the Ku Klux Klan were those forbidding the sale of liquor for sacramental use and repealing the civil rights laws, which would allow discrimination against Negroes. An additional blow aimed at Catholics came in the form of a bill that would stop children in public institutions from attending sectarian schools, some of which were run by the Church. In short: “When the time for introduction of the bills was at end, every one of the bills for the abolition of state boards and bureaus, called for by Governor Morley in his inaugural address, had been laid before the legislature.”

It should not be thought that all bills introduced were concerned with Klan issues or detrimental to the rights of Colorado citizens. An examination of the House and Senate journals shows that many were designed to improve relations between labor and management, help the farming, livestock, and dairy industries, encourage conservation of natural resources, and the like. One bill introduced in the House eliminated primary elections entirely and permitted the convention form of party rule. Later it would pass the legislature and be vetoed by Governor Morley, because through the primary, according to one observer: “Dr. John Galen Locke became the political boss of Colorado….No political convention would have nominated….Morley nor Rice W. Means. The process for them was to command their forces to vote for a certain ticket at the Republican primary, regardless of whether the Klan member so voting was a Democrat or Republican. This gave the Klan control of the Republican party.”

Outside the state legislature, Catholics were bringing about every kind of pressure in order to kill the bill prohibiting the use of wine for sacramental purposes. An editorial in the Denver Catholic Register was reprinted in various publications and circulated throughout at least fifteen different countries. In addition, “Father Matthew Smith was chosen, at a meeting of a group of priests…to celebrate mass as a test if the obnoxious bill became a law and to notify the authorities that he would do so. The Ancient Order of Hibernians heard about the plan with relish and announced that the Irish would be there, let the Kluxers fall where they may.”

Episcopalians supported the Catholics in their opposition to the bill. The Thirty-Ninth Annual Convention of the Episcopal Church in Colorado officially denounced all actions of the Assembly in this respect.

Meanwhile, events within the Assembly were not going as they should for the Morley-Locke program. Introducing bills was one thing, but passing them was quite another. Doubtful Republicans and a handful of Democrats nearly killed a bill abolishing the State Board of Nurses Examiners and brought postponement of its passage; changes were demanded in the wine bills; and four other administration bills were not introduced because of the attack on the nurses’ bill. Republican “leaders herded their charges into conference where lessons were meted out in loyalty to party discipline.” A majority of Republicans attended the conference and all of them attended a secret caucus held several days later in which the governor explained his legislative program. After this brief flareup the House passed all the administration bills.

Governor Morley was faced with an increasingly serious threat to his program in the Senate. The insurgent senators were determined to defeat all phases of it. Their approach was, first, to let the House measures die in committee. Failing this, they would carry the fight to the floor. The six Republicans and fourteen Democrats formed a coalition led by the able Democrat William H. (“Billy”) Adams. It was large enough to kill any bill brought up. Among the reasons cited by the insurgent Republican senators for the action was the fact that the Governor’s administration was not really Republican, since he selected Democrats for key state positions. In addition, he had not once sought out or accepted the advice of party leaders. They also felt that many bills advocated by Morley were intended to eliminate those state employees who had not voted for him in the election. The Senate very much held the whip hand, with its power to bury House measures in committee.

One of the insurgent senators recalls the personal pressures that were put on him. He, as well as the other five senators, opposed all administration bills and refused to go into caucus because he would then be bound to abide by a majority decision on the floor. Consequently, he was ostracized. Hardly anyone would speak to him in the capitol or on the street. Every morning a copy of the unofficial Ku Klux Klan newspaper was placed on his desk. Across the center of the front page was a column with a black border, which was entitled “Roll of Dishonor” and which listed the names of the legislators who had voted against “patriotic” measures. All readers were urged never to forget their names. Governor Morley called the insurgent senator, along with the other un-co-operative Republicans from the upper legislative body, into a conference. Having before him lists of bills introduced by each man, the Governor promised that every bill would fail unless the sponsors agreed to vote for Klan legislation.

As the General Assembly moved into its second month, most administration bills had been passed by the House; they were then promptly placed by the Senate in a committee for eventual extinction. The committees most responsible for letting the bills remain dormant were State Affairs, Finance and Judiciary–all in the control of anti-administration forces. The Labor Committee also had a number of bills, though administration senators were in a majority there. Nevertheless, it feared releasing any measures because they would meet certain defeat on the floor. The Senate did make one concession by allowing a bill to pass that abolished the already-defunct Board of Horseshoe Examiners.

Finally, House leaders stated that all Senate legislation would be sidetracked until the upper house took action on administration measures. This did not trouble anti-administration senators. They knew the other side had more to lose in the deadlock. The administration depended largely for support on representatives from counties outside Denver. Those legislators had been promised, in return for their votes, help in putting through bills which the voters at home wanted. If the deadlock continued indefinitely, there would come an adjournment without positive action; and in that case all legislation would be stifled, including appropriations for every institution of the state, as well as all other essential activities. It was thought that pressure from those outside members would eventually force an ending to the deadlock. Finally, as predicted, the House did begin to pass some Senate bills.

Administration advocates desperately wanted an adjournment, but opposing groups were against it. Senator Louis A. Puffer claimed he needed more time for his Finance Committee to complete its work. Actually the anti-administration forces were trying to force Governor Morley into making his recess appointments while the Senate was in session, so that it could pass on each one of them. This would prevent the Governor from having a free hand to select Klansmen for the appointments.

Efforts of the Senate coalition opposing the Governor gave anti-administration forces in the House some courage. These forces demanded the release of the wine bills from the Temperance Committee. This caused additional embarrassment for Morley. The bills were now feared too drastic for passage and had to be returned to another committee for an eventual death through inaction.

A test vote in the Senate spelled doom for Governor Morley’s entire program. The house bill abolishing the State Board of Charities and Corrections was defeated. The vote revealed that the number of Republican senators opposing the administration program had risen to nine–Samuel Freudenthal, Nathan C. Warren, and William E. Renshaw had joined the original six. After a conference held by John R. Coen, Republican State Chairman with the anti-administration Republican forces in the Senate, it was decided to stand solidly behind the program to oppose the governor by not permitting his bills to be reported out of committee. A tremendous opportunity to carry out that decision came when a Senate resolution was passed naming a Calendar Committee composed entirely of anti-Morley senators. The nine who had killed the bill abolishing the State Board of Charities and Corrections, by joining the Democrats, supported the resolution. This new committee was to make up the daily calendar of bills for consideration during the rest of the session. It could keep off the calendar any bill reported out by a pro-administration committee, and, since there was not a single administration senator on the new committee, a minority report could not even be made.

The Senate did pass needed legislation which was not part of the Morley program. An example of this was the long appropriations bill that provided money for state agencies. The frustrated Governor did what he could to salvage remnants of the program which he and Grand Dragon Locke had devised. He caused the State Board of Charities and Corrections to cease operations by firing its secretary. A related action by Morley was the dismissal of the Negro gubernatorial messenger who had served through many administrations.

The pro-administration legislators in the House put on more pressure for an adjournment, since nothing favorable to their causes could be accomplished. The excuse they made was economy. The Senate would not agree. Even though the Governor had made a number of his recess appointments, there still had to be some guarantee of money for state institutions. This problem was solved by passage of the long appropriations bill, and an adjournment date of April 16 was then fixed by both houses.

As the final day of the Twenty-fifth General Assembly approached, no doubt remained that the Senate coalition headed by Senator Adams had dumped the entire legislative program of Governor Morley. The House made a petty gesture to punish Senator “Billy” Adams by refusing to report out a bill appropriating money for Adams State Normal School at Alamosa. But its real bargaining position was nil; the appropriation measures it once held were gone. They had to be passed for fear of voter reprisal in 1926, and nothing was left in the House except a few maintenance bills. As a last desperate measure the governor called for a conference between the Senate Calendar Committee and the House Rules Committee. He questioned each senator on the Calendar Committee, but no member felt he had a bill important enough to bargain for Morley’s support at the price of releasing one of the administration measures. Their refusal to cooperate only made the Governor demand more. He presented a list of measures he considered vital. The list included such items as bills abolishing the Civil Service Commission; giving his authority to dismiss the Adjutant General; abolishing the State Tax Commission, Board of Corrections, and Board of Capitol Managers; and reorganizing the Game and Fish Department. He demanded that the Calendar Committee not only report out the bills but also guarantee passage by voting in favor of them along with other Republican senators. The only concession made was to report out the Fish and Game Bill, and it was defeated on the floor of the Senate, since it would allow the governor to appoint sixty employees to the reorganized department. At 6:00 p.m., April 17, the legislature at last adjourned.

Disillusioned with the Klan, Grand Dragon Locke organized the Minutemen of America in 1925.

The Twenty-Fifth General Assembly had been in session for an unusually long period–one hundred and one days. During that time 1,080 bills were introduced in both houses, and only fifteen to twenty percent of these were passed. Some of the positive accomplishments of the Assembly were: “The repeal of the state primary law, the ratification of the Colorado River Compact, strengthening of the prohibition laws by enactment of a provision making ownership of a still a penitentiary offense, the placing of bus and auto truck lines under control of the State Public Utilities Commission, providing for the manufacture of automobile license plates at the State penitentiary, providing for the bonding of state officials by the state, providing for the state to carry its own insurance on public buildings.”

Every administration measure met defeat, except the one abolishing the Board of Horseshoe Examiners. Many of the bills were killed in the Senate. The wine bills never even reached the upper house and neither did those repealing the civil rights laws.

A great number of appropriation bills were approved, so many in fact that the revenue of the state could not possibly cover them. The results were ironic; when classification of appropriations had been made by the State Auditing Board, “scores of state departments ceased to exist.”

The Ku Klux Klan was not again to have the political dominance achieved during the meeting of the Colorado Twenty-fifth General Assembly. Though Klan influence was felt in the succeeding Assembly, it was greatly diminished. Governor Morley served but one term, and his successor was none other than William H. Adams, the man who had perhaps been most instrumental in wrecking the legislative program of Grand Dragon Locke. Because of charges against his management of the Klan, Locke resigned from the organization only four months after the legislature adjourned. Before leaving the Klan, however, he formed a new group called the Minute Men of America. With a group of his own creation, he would be the undisputed authority and would not have to answer to any man in Atlanta, Georgia, national headquarters of the Klan.

The Denver Catholic Register gleefully reported the results of the 1926 primary: “In contrast to the primary election two years ago when all the candidates on the Klan ticket were swept into office … Colorado this week vindicated herself to a great extent by denying a second bid for power on the part of the hooded order. The Minute Men, Klan secessionists, also ran low.”

The people of Colorado had at last seen the real nature of the Ku Klux Klan as it appeared in their state–an organization dedicated to furthering the selfish ambitions of leaders by debasing every religious or fraternal body as well as every public office useful to that purpose. Internal corruption and dissension soon brought an end to Colorado’s Invisible Empire.