Story

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46

Countless books, movies, and other media tell the tale of Allied POWs during the Second World War. The very different experiences of the Axis POWs detained on American soil are often overlooked.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Colorado Magazine, we’ve selected some of our best articles from the last hundred years to republish online. This article was originally published in the Summer 1979 edition, and has been reproduced here as it was originally published. Some additional images have been added.

On 7 December 1941, the day that would "live in infamy," the United States became directly involved in World War II. Many events and deeds, heroic or not, have been preserved as historic reminders of that presence in the world conflict. The imprisonment of American soldiers captured in combat was a postwar curiosity to many Americans. Their survival, living conditions, and treatment by the Germans became major considerations in intensive and highly publicized investigations. However, the issue of German prisoners of war (POWs) interned within the United States has been consistently overlooked.

The internment centers for the POWs were located throughout the United States, with different criteria determining the locations of the camps. The first camps were extensions of large military bases where security was more easily accomplished. When the German prisoners proved to be more docile than originally believed, the camps were moved to new locations. The need for laborers most specifically dictated the locations of the camps. The manpower that was available for needs other than the armed forces and the war industries was insufficient, and Colorado, in particular, had a large agricultural industry that desperately needed workers. German prisoners filled this void.

There were forty-eight POW camps in Colorado between 1943 and 1946. Three of these were major base camps, capable of handling large numbers of prisoners. The remaining forty-five were agricultural or other work-related camps. The major base camps in Colorado were at Colorado Springs, Trinidad, and Greeley. Each base camp had several branch camps. Camp Carson (later Fort Carson) at Colorado Springs was by far the largest internment center in Colorado with a POW capacity of 12,000 men, as compared to 2,500 at Trinidad and 3,000 at Greeley.

The yearly prisoner statistics indicate the large number of POWs who were interned in the United States. Between May and October 1943 an average of 20,000 prisoners a month arrived. By November 1944, 281,344 German prisoners were being held in 132 base camps and 334 branch camps, and by April 1945, the number of German POWs had increased to 340,407. The first prisoners shipped to this country, however, were Italian, captured primarily in North Africa in 1942.

Several hundred were sent to Colorado Springs and the army installation at Camp Carson. Following the successful Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943, the Mussolini dictatorship in Italy was overthrown by the Bagdolio coup, and since the Bagdolio government was favorable to the Allies, all forms of treatment of Italian POWs were relaxed in 1943. Many of the prisoners were formed into service units and actively aided the Allied cause for the duration of the war. In the summer of 1943 the Italians at Camp Carson were evacuated and replaced by German prisoners captured in further Allied advances in North Africa.

These early German POWs were the remnants of Rommel's crack Afrika Korps—panzer tank crews and infantrymen. Before their induction into the German army , they were technicians, artisans, and workers from every imaginable walk of life. They could be described as disciplined, arrogant, proud, and primarily young.

The administration of the internment camps was the responsibility of the United States Army Provost Marshal General's Office. The Colorado area was administered by the Seventh Service Command with headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska. In terms of such a large-scale program, there was no precedent in United States history. The camps were administered according to the "bible" of prisoner internment, the Geneva Convention. This was the "constitution" that ultimately shaped all policy decisions regarding the operation of the camps and the treatment of the prisoners. In spite of a claim by the commanding officer at Camp Carson that his guards consisted of ''the usual surplus of psycho-neurotics and ill-disciplined soldiers," the German prisoners, in general , were afforded relatively good treatment by their American captors. In comparison with their American counterparts in Germany, they were treated exceptionally well. Not only the army but also the International Red Cross regularly investigated the internment camps to determine if Geneva guidelines were being strictly adhered to by the camp administrators. According to the Denver Post, the Red Cross found that the Germans were well treated not only in Colorado camps, but also in all of the other United States internment centers. It was believed that the treatment of the German prisoners in America directly affected the treatment of the American captives in German camps.

The architecture and appearance of the base camps in the United States were similar to that of the German camps. Nine- to ten-foot high barbed wire fences, sometimes two to three layers deep, and heavily armed, elevated guard towers with night searchlights encircled the camp. Barrack dormitories housed the prisoners at the base camp, and at the branch camps the men usually were housed in industrial dormitories, armories, or old Civilian Conservation Corps barracks, sometimes without any prohibiting security enclosures. The camps were generally separated into compounds. A standard compound consisted of twenty barracks, each capable of quartering fifty men. In addition, there were four kitchens and accompanying mess halls, four wash and laundry facilities, and four officer rooms.

As specified in the Geneva Convention, the German POWs were permitted to wear their army uniforms within the camps, as was the case with American POWs in Europe. Since the majority of these captives were from Rommel's panzer divisions in North Africa, the sight of muscular German youths parading within the camp compounds in their Afrika Korps uniforms was common. Even in the cold Colorado winter months, some of these prisoners wore their desert shorts and short-sleeved shirts. American and German officers exchanged salutes in the camps as dictated by the guidelines. The prisoners were considered equals, men unfortunately captured in the course of war. In the letters destined for the homeland, censored by the Army Office of Censorship, many moving emotions and a number of blatant grievances were expressed by the captives. One German captive at Trinidad wrote that "they transported us like the lowest criminals about which they seem to have plenty of experience in this country…conditions here are indescribable and primitive…four of us in a room; no tables or chairs.” However, the benevolent treatment received by the German POWs is evidenced by their return to Colorado following the war. A Catholic priest, the Reverend Leo Patrick, regularly associated with prisoners in Brush while on religious errands. He persuaded some of the prisoners to return to Colorado, and one prisoner, Nahomed Mueller, sent his son to live with Rev. Patrick and to attend Brush High School from 1950 to 1952.

The relatively favorable treatment accorded the German POWs generated criticism from the public sector of American society. The army defended its administration by contending that the criticisms were due to a lack of knowledge of the Geneva Convention and the applicable international law. A congressional investigation responded to the public, stating that "treatment is not a question of army policy but a question of law."

A charge of preferential treatment of the German captives was made at Camp Trinidad. The situation was attributed to the commanding officer, whose removal from duty was sought by Americans administering the camp because of his "unAmerican ideas, his coddling and catering to the German prisoners, and his inhuman treatment of all American personnel." The American soldiers at Camp Hale tell of a similar situation. Andrew Hastings, a member of the Tenth Mountain Division Ski Troop, recalled German POWs marching and singing every morning. "It used to make us mad as hell because the Germans were singing their songs as they marched and the U.S. Army wouldn't let us sing!" At Camp Carson, however, a prisoner spokesman claimed that an army soldier threw tear gas at a truckload of Germans as they were being transported to a work site. Carson authorities claimed that the captives were not guinea pigs for army maneuvers but were "inadvertently driven through a tear gas demonstration on the main post.”

Daily life for the POWs varied only slightly from camp to camp. They rise to the sound of the bugle at 5:00 A.M. and spent most of their day at various work projects. The army attempted to allow the Germans to engage in activities similar to their prewar vocations. The artisans naturally were more content than the laborers. While recreational facilities were limited, physical activity was encouraged. At most camps, teams were organized for competition in various sports. For example, during February 1946, ninety-seven different sports events were held at Camp Carson, and ninety-nine musicians staged eighteen concerts. Catholic or other religious services were common in the camps, with religion practiced freely and fervently.

The diet of the prisoners was equivalent to the rations of American combat soldiers overseas in the early months of the war. However, the army altered the menu, claiming a shortage of food, but the policy can probably be attributed to increasing public pressure. In the early years of the war, the public questioned the food policies of the army, contending that the German prisoners were fed better than armed forces personnel. The Office of the Army Provost Marshal General defended its policy publicly, explaining that German cooks were given the rations and allowed to prepare them in any manner which they chose. The cooks were experienced and exceptionally imaginative and, therefore, prepared the rations rather well for their comrades behind the wire. On 1 July 1944 the army instituted its food conservation program within the internment camps. In February 1945 the food policy was tightened again with substitutes for sugar, butter, and beef. “John Hasslacher, a former prisoner at Camp Trinidad, Colorado, remembered that food was not ideal, but there was enough meat and variety until V-E Day. 'The moment the war was over,...the daily rations consisted of: Porridge with a bit of milk in the mornings, pea soup with lettuce salad and a slice of soft bread…at noon and in the evening.’” A ration for one prisoner cost the United States twenty-five cents.

An illustration of the Sangre de Cristo mountains from the camp, including Fishers Peak (on the far right), by German POW Wilhelm Herbrechtsmeier. The caption reads “Pastels: Mountainous Terrain.” Hebrechstmeier created many such art during his time at the POW camp in Trinidad, and after the war compiled them into three albums that are now in History Colorado’s care.

One of the benefits that the German POWs received was their pay-paid, however, by the United States government. Payment was not in cash, but local banks would maintain credit for the prisoners or the camp canteen would issue coupons for the purchase of necessary supplies. Officers were not required to work, yet they received an allowance of twenty, thirty, or forty dollars a month depending on their rank. Enlisted men received ten cents per day to cover basic essentials such as toothpaste, razor blades, and tobacco. The government claimed that these allowances would be repaid by Germany following the war. In addition, the prisoners received eighty cents per day for any labor performed for the benefit of the United States.

Interesting insights into the lives of the prisoners can be gleaned from the publications produced within the camps. None of these was, of course, political in content. They were entertaining and provided information to the prisoners. The Camp Carson prisoners published Die PW Wolke [The POW Weekly]. Rӓtsel Humor [Fun With Puzzles], published at Camp Greeley in 1944-45, primarily concentrated on amusing the captives with crossword puzzles, songs, and cartoons. In contrast, Deutsche Kriegsgefangenschaft [German Prisoner of War]: Colorado-Amerika, 1944-45, apparently also published at the Greeley camp, was literary and more sentimental in nature, which makes it more enlightening concerning the prisoners' daily lives and thoughts. This publication contains descriptions of Colorado written by the POWs. They wrote of their fascination with the Moffat Tunnel as an engineering feat and marveled at the beauty of the countryside, especially the Rocky Mountains. The Colorado peaks were more jagged and dynamic than the old and worn mountains of their homeland. In addition, place names of the communities interested the POWs. Particular attention was paid to the work side camps and their origin. They wrote of Boulder, Fraser, and Deadman Mountain, all side camps of the Greeley installation. The rivers of Colorado were compared with the Mississippi River. The Columbine, the Colorado state flower, was explicitly defined and illustrated. Thus, the publications were a form of education, containing valuable information for the prisoners.

Popular American publications were distributed among the POWs as well. They included daily newspapers such as the New York Times and the Denver Rocky Mountain News, and such magazines as Life, Time, Look, Newsweek, Saturday Evening Post, and Esquire, even though commanding officers complained that Esquire contradicted the army policy of withholding oversexed media from the POWs.

Life in the camps was not always a routine of work and recreational activities. At various times during their internment, the prisoners would refuse to work. The response of the army was immediate disciplinary action. A "no work, no eat" policy proved extremely successful when these sit-down strikes occurred. Most of these strikes were inspired by Nazi influence within the camps.

A group of German POWs entering a building at the camp in Trinidad. They were photographed returning from the funeral of an officer who died during internment at the camp.

Another factor that produced ill feelings was the policy of not allowing the army personnel to fraternize with the prisoners. Although policy was interpreted more liberally by some camp administrators than by others, it was particularly frustrating to camp personnel who supervised prisoners' work assignments, as they felt that it hampered work production. Fraternization between prisoners and civilians was strictly forbidden for security reasons. However, this was not always effective. A Del Norte woman engaged in a romantic affair with a German prisoner stationed there at a side camp. For several months she would drive her car out to a farm road in the evenings where the prisoner would be waiting; then they would return to her home in Del Norte. When the relationship was discovered, no action was brought against the woman, even though the incident titillated the social circles of Del Norte for some time. The prisoner was sent back to his base camp at Trinidad.

Ironically, the POW internment system in the United States provided valuable assistance to the agricultural industry through the Emergency Farm Labor Program. The army also viewed the farm-labor program, which allowed prisoners to be transported to and employed in areas in need of labor assistance, as an important feature of the internment system. Due to the tremendous manpower resources demanded by the armed forces and the war industries, acute labor shortages occurred in the agricultural sector, including Colorado. Harvest crews were particularly needed because crops lay rotting in the fields; thus, side camps were built to accommodate the need for additional farm labor.

Although the Farm Security Administration had made arrangements to import Mexicans and local schools and communities cooperated, the labor force was still insufficient to assure a good crop. At the Agricultural Farm Labor Conference in Salt Lake City on 1 May 1943, the War Department suggested that POWs could be utilized to alleviate the labor shortage and that additional camps should be located with that consideration in mind. The Colorado Extension Service immediately requested a camp near Greeley, an important sugar beet production area, and the camp was ready for occupancy in early 1944.

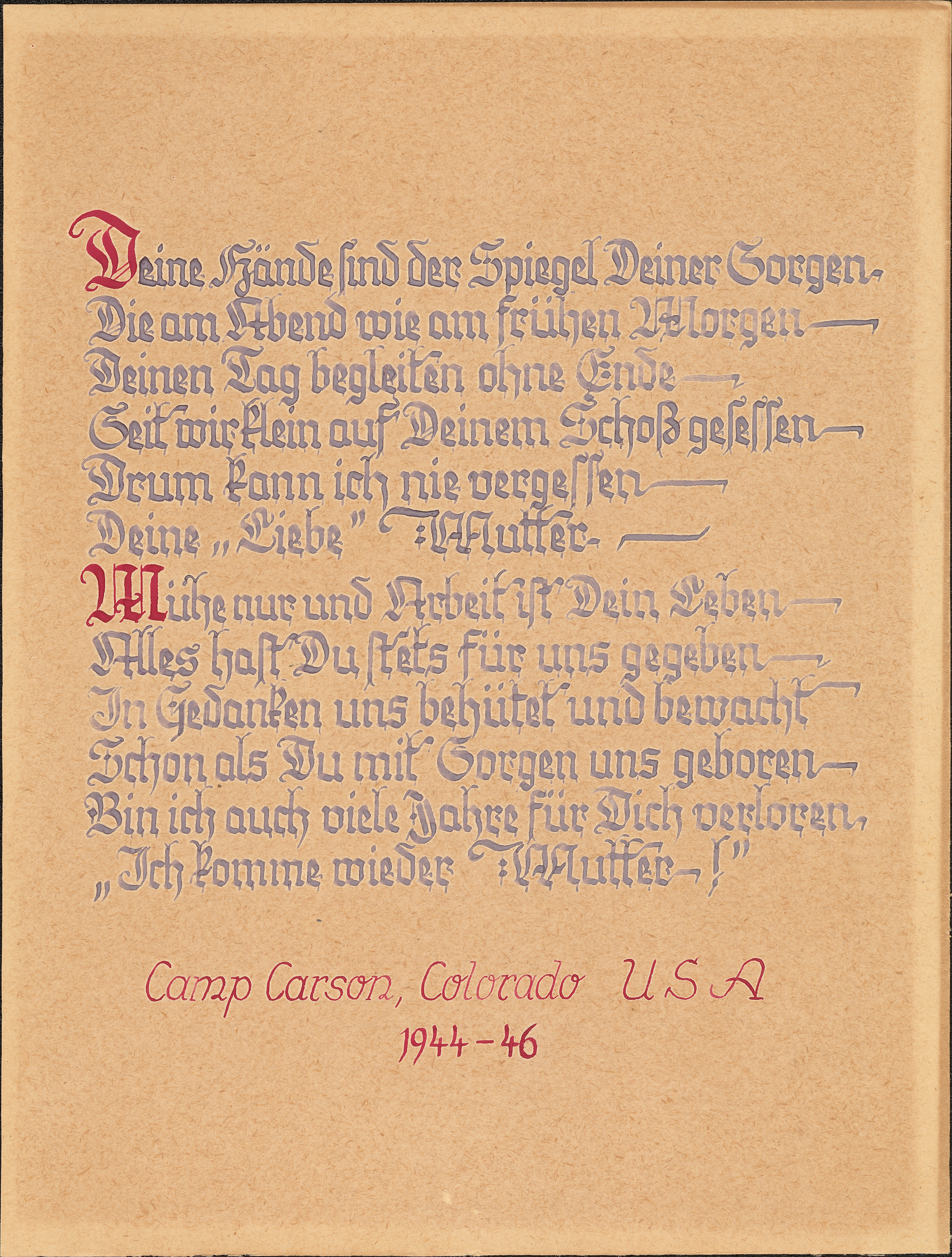

A framed German poem created by POW Jakob Biehl during his time at Camp Carson.

Authorization was given to the Extension Service to negotiate directly with the War Department for POW labor. In Colorado, the Extension Service divided the state into districts to administer the farm-labor program, and it also worked very closely with county agents, county labor organizations, and private firms to coordinate the placement and the utilization of the workers. A placement office was maintained at the Greeley camp during the busiest work seasons and at most of the larger camps during the 1945 harvest. From fall 1943 to spring 1946 the POWs were a major factor in the farm-labor force in Colorado.

The first time the POWs harvested beets in 1943 the yield averaged about one and one-half tons per man per day. Through improved methods of training and supervision, the average rose to about four tons in 1945. Such impressive results were not initially foreseen by the farmers and the communities, for they were concerned about the security risks and the possible crop loss. Immediately after the first harvest season, however, the results were applauded by the farmers. A newspaper headline told the story: "War Prisoners Earn Way, Farmers Agree."

Other advantages of using POWs as a labor force became apparent to the farmers and the government officials. Because of the demands of war, Trinidad had declined, but it boomed again when construction began on the POW camp. "Every hotel room, house and apartment in Trinidad is full, every citizen who wants to work has a job and hundreds of new workers and their families have migrated to the city." Using POWs also highlighted the employer-employee relationship. While "the use of prisoners of war relieved employers of nearly all direct relationship problems with workers" and "on the whole, Colorado farmers liked this type of labor very much after they got used to it,'' this indirect relationship pointed out the need for an educational program directed toward the farmer. With wages for laborers rising, the POWs also proved to be less expensive for farmers. The Geneva Convention states that prisoners employed by private employers must be compensated; however, the federal government received most of the profits from this type of transaction. In 1944 the Ault-Eaton area harvest program had 330 POWs who harvested $712,208 worth of crops for 291 farmers. From these two areas the federal government earned an estimated gross of $135,954; the net profit for the government, after deductions were made for housing and feeding the prisoners, was $99,545. These were crops that might otherwise have been left to rot in the fields.

Besides being the highest military post in the nation, Camp Hale was one of the most scenic. This view is from the north, looking south.

Many mistakes were made in using POWs in the farm-labor experiment. Work production continually necessitated increased yields, and various techniques were applied to the prisoners to achieve this end. At Eaton the farmers tried giving the POWs sandwiches and cases of beer in hopes of getting more work out of them. The Germans interpreted this kindness and cajoling as fear and their work yield began to wane; this lenient treatment stopped. On 16 June 1946, using POWs in the farm-labor program officially ended and on 31 December 1947 the Emergency Farm Labor Program concluded, deemed a success.

Another program, one more difficult to evaluate, was the move to "democratize" the German captives. The army questioned the validity and the effectiveness of such a program. Despite the objections of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, however, the Special Projects Division of the army undertook the task of politically educating the German POWs. It was an experiment in a "democratic leadership" for postwar Germany. Books that had been banned by Hitler's Nazi regime and books "representative of the American spirit" were distributed in the camps. Abe Lincoln in Illinois was one such book that was widely circulated. Several Colorado universities contributed books from their libraries, and educational degrees were available to POWs through the coordination of the Swiss and German governments.

As the Allied victory in Europe appeared imminent, the political education program evolved more rapidly in preparation for the prisoners' return to their homeland. The moving force behind the Intellectual Diversion Program was Colonel Edward Davison, a former faculty member of the University of Colorado. Emphasis began to shift from the original "Americanization" aims to three new objectives: "to awaken or sharpen the feeling for the political responsibility of the citizen; to arouse a capacity for spontaneity on the part of men whose training and education had placed a special value on obedience and a respect for hierarchy; and to provide sorely needed encouragement to men who were asked to welcome the ruin of their individual and collective existence as the precondition of a new 'good life.''' The German people would need new leadership, and four special training centers were established for this purpose. Although there were no centers in Colorado, the Colorado camps participated in choosing men for the program.

The German internment camps did not receive much publicity during or after the war, being overshadowed by events overseas. However, occasional escape attempts from the camps produced sensational news stories. Because of the tremendous manpower required by the armed forces and the war industries, the camps were operated on a "calculated risk'' policy. Escapes were a plausible and accepted phenomenon by the army. However, the public did not fully appreciate this policy and disliked the idea of the enemy freely roaming the countryside. There were approximately forty-seven thousand soldiers guarding the POWs, which was only fourteen percent of the total POW population. The guards were strictly perimeter guards, so no armed patrol circulated within the camp proper. Dogs were used to walk the perimeter of the camps, especially at night, and the Carson and Greeley camps used these animals extensively.

A prisoner will employ ingenious means to effect his escape. Within the inter-camp exchange, the Germans' ability to gather information relating to escapes was remarkable. When the army investigated German escape tactics, they uncovered several enlightening procedures that were utilized. They also found that the prisoners knew the exact train schedules in the locality of the camps. The people in Germany aided this effort by sending secret information in letters. To combat the exchange of mail with the homeland, the army issued special stationery that turned green anytime moisture contacted it. This was an unsuccessful attempt to halt any attempts at secret nonvisible writing, but the prisoners soon discovered that by placing wax paper over the stationery they could still conceal a message.

The Germans were also very adept at forging counterfeit documents. Army induction cards and birth certificates were produced in large quantities. The Germans, believing that any document with a rubber stamp on it looked authentic and official, fabricated rubber stamps by cutting off the end of a raw potato, carving the desired lettering, dipping the stamp in an ink dye, and stamping the falsified documents. Although prisoners were forbidden to possess any American currency, they managed to acquire it. In one instance, the army discovered that one prisoner had concealed money in his pet dog. A small slit had been cut in the outer fur, the money inserted, and the skin then sewn together.

During the war 2,671 POWs escaped from the internment camps within the United States, and Colorado contributed to this statistic. Most of the escapees would flee to Central or South American ports where cargo ships were destined for German-occupied soil. The journey from Colorado, however, was difficult, and the Afrika Korps uniforms were easily identified and provided inadequate protection from the cold Colorado nights.

It was relatively easy for prisoners to walk away from the branch work camps, for security was almost nonexistent. The prisoners at the Brush camp were even allowed to attend Sunday morning services at the community Catholic parish without guards. Three POWs walked away from the agricultural camp at Fruita near Grand Junction while harvesting beets, but they were apprehended the following morning when a farm boy spotted them sleeping in a haystack and notified the authorities. Three prisoners also left the Rocky Mountain Arsenal Camp to visit Denver, and they were picked up by a state trooper who noticed them walking down a nearby highway.

The camp at Trinidad was riddled with escape attempts. Several prisoners systematically escaped from this compound until a tunnel 150 feet long, 5 feet high, and 30 inches wide was discovered by guards. The tunnel ran to a point 65 feet beyond the beam of the night searchlight, which skimmed the outreaches of the camp. The tunnel was entered through a trap door in the German officers' compound. A reporter at the Denver Post later claimed that Japanese-American women employed at nearby farms gave the German captives crude implements to dig the tunnel, which was completed in one month. The Denver Post may have been correct, but this particular allegation was never proven. However, the discovery of the tunnel and the involvement of American citizens aiding the enemy provided an interesting perspective into the administration and the security problems at the internment centers.

Around ten in the evening of 4 September 1943 Karl Gallowitz, a lieutenant in the Luftwaffe, and his companion Horst Erb escaped from Compound 4 in the Trinidad camp. They had both fashioned their Afrika Korps uniforms to resemble those of American Boy Scouts. At 12:15 P.M. on 5 September 1943 their absence from the camp was discovered when they did not respond to their names during roll call. Two other German captives, Gustaf Wilhelm and Willie Weineg of Compound 4, also were missing. A general alert was sounded and Karl and Horst were almost immediately discovered near a farm to the west of Trinidad. Not only was the pair apprehended with seven dollars of United States currency but they apparently had bought bacon without any food ration stamps, indicating the cooperation of someone in or near Trinidad. Soon after, Wilhelm and Weineg were apprehended heading in the direction of the New Mexican border. Army investigation reports reveal that both Gallowitz and Erb claimed that they had escaped through a fence in Compound 3. No wire cuts could be found to support this claim. An informer told investigators that the pair had jumped over Gate 1 in Compound 4 between guard changes at 10:00 P.M. The guards testified that the gate in question was only out of sight of the sentries for three seconds during the change. The investigative report stated that "the testimony of the prisoners themselves have [sic] many contradictory statements and cannot be relied upon," and the report concluded that ''the prisoners escaped by unknown means.'' Both Wilhelm and Weineg refused to state how they escaped. Nowhere in the investigation report is there a mention of the possibility of a tunnel route for escape, even though four POWs escaped in one evening by suspicious means.

The Trinidad tunnel saga became even more interesting one month later. Word had circulated among the prisoners regarding some friendly women who worked on a nearby farm where a work detail of German captives regularly worked. POW Heinrich Haider felt this provided a much-needed opportunity to solicit aid for an escape. On 9 October 1943 Haider assumed the name of another POW and slipped into a harvesting work detail destined for the farm, which was located about ten miles from Trinidad. Five sisters, all American citizens of Japanese ancestry, worked and lived on the farm. It was a blistering hot Colorado day, and on a work break Haider made his way to the small farmhouse kitchen for a drink of water. Alone with the girls, Haider, speaking excellent English, suddenly switched from a flirtatious conversation to a low whisper, asking for civilian supplies to aid in an escape. One of the girls, whose name was Tsuruho Wallace, also known as "Toots" locally, replied, "We'll see what we can do." On the same day the girls took souvenir photos with Haider in the fields.

Two days later Haider again assumed another prisoner's name and found himself on the same work detail on the farm. He worked most of the day without any contact with the girls, who were working nearby. At 3:00 P.M. he sat down to relax from his harvesting task. Within moments he heard a girl's voice from behind telling him that he would ''find a package in the bushes near [his] lunch basket.'' He found the package and inside were two blue hats, two pair of pants, two shirts, several road maps, and prints of the souvenir pictures taken with the girls just two days previously. Haider smuggled the package back into Compound 4 where he divided the spoils with Martin Bazkes and Herman Loescher. On the evening of 15 October 1943 Martin Bazkes, Heinrich Bente, Heinz Echold, and Julio Hoffman fled into the open country beyond the fences. Two hours later, in the early morning hours of 16 October 1943, Haider and Herman Loescher entered the tunnel and made their way to freedom. Their freedom was short-lived. All six escapees were soon apprehended by local authorities and returned to the camp for interrogation.

The American investigators had been frustrated in their attempts to determine the means of escape until Julio Hoffman finally relented under questioning. He had learned of the tunnel two and one-half months before, after it had already been completed. He was told that it had taken twenty-six nights to build and that the dirt excavated from the tunnel had been secretly mixed with topsoil in the flower beds surrounding the barracks. Hoffman further revealed that Karl Gallowitz and Horst Erb had escaped through the tunnel on 5 September and that construction was in progress on two more tunnels within the same compound. It was not until 6 November 1943 that the army investigators finally found the completed tunnel and the two currently under construction. The main tunnel was discovered in Barrack 1271, the opening being in a closet where floorboards had been removed and lumber, dirt, and rocks concealed the entrance.

With Haider's capture the souvenir pictures of him with the Japanese-American girls on the work farm were confiscated by the American authorities. Investigators eventually found the girls, but Haider refused to implicate them in any way. Finally, "Toots" was positively identified as having purchased the road maps found with Haider, but further evidence eluded the officials, causing them to drop all charges connecting the girls with the escape even though Haider eventually related the entire tale. Throughout these months of escapes, the army officials displayed an obvious lack of professionalism. Even after several successful escapes during the month of September, where the escape tactics were a mystery to investigators, no general search was ever conducted.

Perhaps the most sensational and publicized escape occurred at the Camp Hale installation. Approximately three hundred German prisoners were detained there, high in the Rocky Mountains near Leadville. The prisoners performed general sanitary and maintenance work for the Camp Hale center, which housed the specialized and famed Tenth Mountain Division Ski Troops. The escape was apparently orchestrated by Dale Maple, an American stationed at Camp Hale with the 620th General Engineering Corps, a unit composed of about two hundred men. They were labeled engineers, but in fact knew little about engineering. They were antiwar sympathizers and some were suspected of being pro-Nazi. "The 620th general services consisted of making camouflage nets, digging ditches, sawing wood, and performing other tasks of a more or less menial and insensitive nature." The men of this unit were not issued guns or given sensitive assignments.

Dale Maple had graduated first out of a class of 585 in high school and had also graduated cum laude from Harvard. While at Harvard, he was ousted from the Army ROTC program for singing Nazi songs at the meetings. When war broke out with Germany, Maple unsuccessfully tried to leave with the departing Washington, D.C., German embassy corps in hopes of joining the German army . He was then assigned to the 620th because of his questionable loyalty to the United States.

Members of the 620th participated in and planned many illegal activities that aided escapees and furthered the Nazi cause. They had "maps of Central and South America , documents relating to the administration of the 620th stolen from the company commander's trash basket, and tables of organization for guerrilla forces." Sabotage operations were also planned by the group. On several occasions the 620th generously entertained their German captives. One prisoner spent several days traveling in northwestern Colorado visiting hamburger stands and beer joints with two members of the unit after having been supplied with an American uniform and currency. He later told authorities, "I have seen beautiful America."

During a leave of absence, Maple spent his vacation with German POWs in Camp Hale. Dressed in an Afrika Korps uniform, he hid in the back of a truck and stole into the German compound where he spent three days joyously singing and drinking with the captives. It was at this time that Maple persuaded two prisoners to accompany him on an escape attempt. Having solicited his Nazi companions, Maple bought a car in Salida, reported in sick, and drove the two Germans to the Mexican border where the vehicle broke down. On 18 February 1944 Maple and the two Nazi POWs were arrested by a Mexican immigration official, three miles inside the Mexican border. They were picked up on a farm road seldom used by tourists, waving American and Mexican flags as if to convince the officer that they were not escapees but tourists. If the official had not suspected that they were the participants in a recent escape from a Texas camp, they might have succeeded. The details are numerous and complicated, but eventually Dale Maple was court martialed for the military equivalent of treason. He was convicted and sentenced to death, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt commuted the sentence to life.

There were two instances in Colorado of prisoner fatalities resulting from gunshot wounds. At the Trinidad camp a POW was fatally shot when a guard apparently "got excited" as the prisoner ventured too near a perimeter fence. At Fort Morgan, a POW was killed as he charged a guard in an alley behind the prisoner compound. Four Germans had escaped the night before, and although three of them had slipped back into the camp by morning, the guards were taking no chances.

It is perhaps understandable that the public criticized the security in the camps. The army responded to this criticism by publishing a report to Congress. "As of the year ending June 30, 1944, federal prisons had an average population of 15,691 from which 60 men escaped for a rate of 0.44 of 1 percent. During the same period, the average POW population was 288,292 with 1,036 escapes for a rate of 0.45 of 1 percent. When you consider that federal penitentiaries have sophisticated and modern devices (designed to eliminate escape) compared to a line or two of barbed wire with most guards carrying guns ruled unfit for combat, this percentage is impressive." However, the army report conveniently studied only the first year of German internment in this country. The average monthly escape rate from June 1944 to August 1945 was over one hundred, an average of three to four escapes per day. It is interesting to note that despite public fears, the records indicate that no escaped POW ever committed an act of sabotage against the United States.

Aside from the continuous accumulation of fraudulent documents and the development of tactics to aid their flight to freedom, the Germans provided themselves with means to enjoy their captivity. Illegal and secretive production of liquor was a favorite pastime of the prisoners. They sorely missed their German ale, but they were ingenious in making substitutes. Liquor stills were discovered periodically in the compounds, usually hidden in the walls of the barracks. The Denver Post reported on 7 March 1944 that three to four stills and forty to fifty gallons of liquor were seized at Camp Hale. At the Trinidad camp the German blacksmith frequently went to work "drunk as a skunk." The operation of stills in Trinidad was openly acknowledged by the camp commanding officer in 1945.

Nazi violence within the camps was a security problem that proved to be a national trend. From September 1943 to April 1944 fanatical Nazis attempted to seize control of the internment camps by coercion. "Within that period, six murders, two forced suicides, forty-three voluntary suicides, a general camp riot, and hundreds of localized acts of violence occurred. In every instance, investigation by army authorities pointed directly to the influence of hard-core Nazis, which followed a pattern that saw the prisoners accused by their comrades of anti-Nazi activities, sentenced by kangaroo courts, and hanged, beaten, or coerced to death by Gestapo methods." The army subsequently attempted to isolate hard-core Nazis within the camps and interned them at a special high-security camp at Alva, Oklahoma. Identifying these individuals was usually done by informers. Intelligence officers at Carson, Greeley, and Trinidad utilized informers extensively. Trinidad apparently was more of a haven for Nazi activity than any other camp in the region. In a preliminary report on intelligence to the provost marshal, Lieutenant Schoenstedt stated that "all information received in connection with Camp Trinidad points to a very strong Nazi group which controls the whole camp." Consequently, the army considered Trinidad to be one of the most important centers in the country for counterintelligence work.

Despite the burdening problem of security, the internment program during World War II proved to be successful. The Emergency Farm Labor Program in Colorado helped save several harvests. The educational programs attempted to prepare Germans for a new Germany. Regardless of civilian apprehension, acts of sabotage were not committed by escaped POWs and no POWs remained at large from Colorado camps during or after the war. The German prisoners were treated well, according to the Geneva Convention, and morale was generally better than could be expected from POWs held captive thousands of miles from their homeland.