Story

The Women of Market Street

A Glimpse into the Lives of Denver’s Nineteenth-Century Sex Workers

Denver’s red-light district was the worst-kept secret in town, and the women who plied their trade there lived on the margins of society. Their stories reveal pain and violence, but also hope and sisterhood at a time when few had anywhere else to turn.

"Essentially mean, dishonest, low characters not deserving immortality" were the words Denver Post book editor Stanton Peckham chose to describe Denver’s early sex workers.

His bile was aimed at the women filling the pages of Caroline Bancroft’s book, Six Racy Madams of Colorado. In his rather narrow review of the book first published in 1965, he questioned whether "these women" were worthy of Bancroft’s painstaking research, engaged as they were in the “indispensable vocation” (read: sex work) along Market Street in today’s LoDo area of Denver.

Also known as The Row, Market Street between Eighteenth and Twenty-Third Streets teemed with opulent parlor houses, common brothels, and lowly cribs where women sold companionship in the later half of the 1800s and into the early 1900s. For these women living on society’s margins, the nature of the work mingled with repressive and moralizing Victorian sensibilities, leaving them vulnerable to all kinds of predatory behaviors. Violence, sexual assault, suicide, addiction, and financial insecurity were common in the lives of women who worked Denver’s Row. But they also found camaraderie, agency, and a degree of financial independence—avenues for personal fulfillment that were often unattainable for women in more socially acceptable roles. What Peckham and others missed as they enunciated their low opinions was that, for many women in the burgeoning American West, “the life” was the most promising way to better their financial circumstances, escape lives of drudgery, or find the means to simply exist.

Three brick parlor houses or brothels along Holladay Street, later Market Street, in early Denver, Colorado.

What follows is a reflection on the nature of life in Market Street’s red-light district, a detailed observation of the lives of the women who worked there, and an investigation into a side of history that is often overlooked. Revealed are stories about the dangers and difficulties these women faced in the lives they built—but also moments of compassion, of humor, and of humanity. However judged or overlooked, these women’s lives are an important part of Denver’s history. They are stories about people who, one way or another, were seeking a better life.

Sisterhood of Soiled Doves

Soiled doves, ladies of the evening, frail sisters, nymphs du pave, cyprians—the women of The Row went by many names. Their reasons for taking up sex work were as varied as the common euphemisms polite society came up with for their jobs, reflecting the clandestine and hushed nature of the way Victorian-era society marginalized these women. Denver’s nineteenth-century sex workers were ostracized and segregated from a society that viewed them as a social—albeit necessary—evil. Sex workers in Denver and beyond developed close-knit bonds with their fellow workers, which was important because living on the margins meant dangers and opportunities in equal measure.

Although never legalized, sex work was tolerated as long as it was hidden and contained within the confines of the red-light district. Parlor houses and brothels served as private communities where women in the profession ate, slept, confided in each other, fought with one another, stole from each other, and were provided a degree of comfort and familiarity in a hostile city.

In a society that devalued women generally, and specifically those who worked in the sex trade, the so-called frail sisterhood offered a way for women to adapt to and function within the profession. Lacking much in the way of safety nets, women in turn-of-the-century Colorado were often left with only extremely limited choices if they fell on hard times. Historian Ruth Rosen describes the soiled dove sorority as a subculture offering belonging, support, and human validation. Especially at that time, divorce, desertion, or death of a wage-earning father or husband could throw a woman’s economic security into disarray. Women with no occupation, education, or training might turn to sex work as a last resort. Given the ease of making a living selling companionship to lonely miners, ranchers, and businessmen coming to Denver, the majority of women who chose sex work did so because they needed to pay rent, buy food, and support themselves or their families.

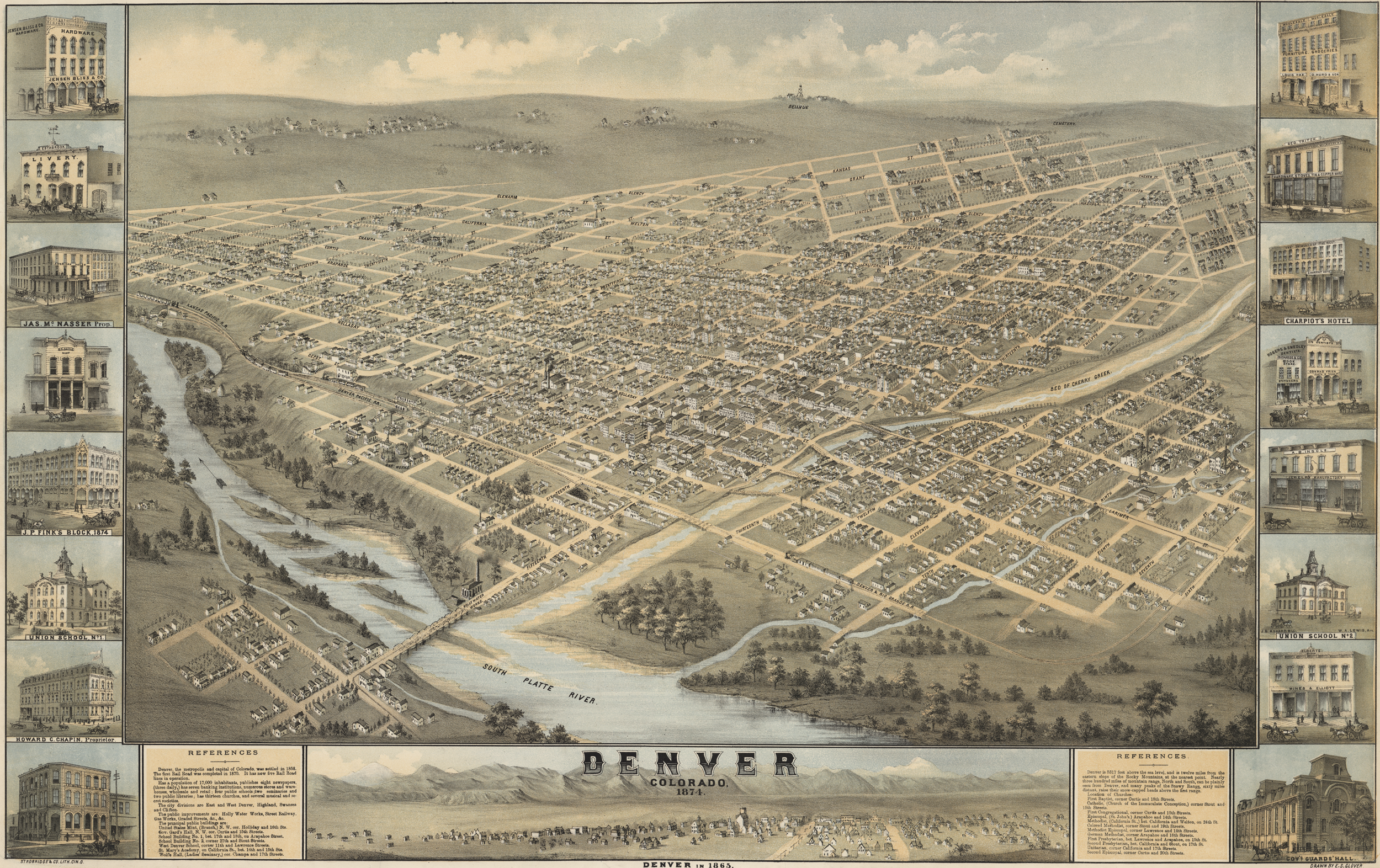

Bird’s-eye view of Denver from the North West looking South East, 1874.

Subsistence wages for “respectable work” were much lower that what women could make working the red-light district, and sex work certainly had less of the drudgery of working as seamstress, laundress, shop girl, or domestic servant—some of the limited options available to working women at the time. Lillian “Lil” Powers, later the proprietress of The Cupolo at 1947 Market Street, was known as “The Laundry Queen,” having left that line of work for the oldest profession. She recalled working in a laundry in her early years in Denver:

I got a job in a laundry and if you think that was easy, my God!...it was almost as bad as the farm and my pay was one dollar a week. My room cost me fifty cents a week—there wasn’t much left for all the fancy folderols I thought I could buy when I went to the city.

Some women like Powers came to Denver for the excitement and glamor of the city. The allure of Denver was the idea that women could make easy money and achieve a measure of financial or personal independence not available in the more rural parts of the state. In fact, one of Colorado’s most notorious madams, Laura Evans, said in an interview, “I didn’t know anything about this business in Denver. But I fell very readily into it…the money’s so fast…and everything…excitement.” The interviewer asked, “You say a girl could get seventy-five dollars a night?” Evans answered, “Oooh! That wasn’t anything.…Paydays make a couple hundred…you just helped yourself to what they had. You let a miner go back up the mountain with any money, they’d think you were crazy.” Or simply put, from the letters of a working girl in New Orleans’s Storyville: “I just cannot be moral enough to see where drudgery is better than a life of easy vice.”

But the life of vice wasn’t always so easy. The business of sex work was hard and often physically threatening or economically precarious. Poverty, violence, drug overdoses, and suicide were constant companions for women on The Row. And a dove’s death, from any cause, didn’t result in the traditional funeral arrangements. According to Anne Butler in her book Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery, sudden deaths required quick burials, and many women lacked family who could, or would want to, take care of the final arrangements. Often their fellow “sisters-in-shame” willingly stepped up and managed the proceedings. From raising subscriptions to pay for funeral accoutrement to acting as pallbearers and mourners, the women of the frail sisterhood took care of their own until the end. The following, published in the Rocky Mountain News on March 3, 1881, described the memorial service for Mattie Woods who died in a parlor house at 500 Holladay Street, run by Mattie Silks.

All that was mortal of Mattie Woods, the poor cyprian who ended her life on last Monday night, was laid away to rest in quiet, peaceful Riverside yesterday afternoon. The obsequies were conducted from Brown’s undertaking rooms on Lawrence Street, and were of a simple and unostentatious nature. The rooms were thronged with friends who had known the dead woman during life, and there were many kind words of love and pity spoken. Cheeks which have long forgotten a virtuous blush were tear-stained and many painted lips were parted in silent prayer for the repose of their erring sister’s soul. Twenty women in all were present, and their sincere grief seemed to soften and lessen their social sins to the few spectators who had been attracted to the scene through curiosity. The coffin stood near the center of the room and bore a burden of floral offerings. At the head was a large wreath and cross of sweet immortelles and bouquets were arranged about for the foot. Within, the tired body rested, and the face looked pure and almost saintly. The burial robes were of a rich and appropriate texture and in fit keeping with the perfect arrangements for the last sad rites so commendably prepared by the women who provided them.

The article’s moralizing tone and the tinge of spectacle epitomized the press’ attitude of scorn and sentimentality when it came to the lives and deaths of women who lived outside the pale of polite society. Yet the care these women took with burying their dead seemed a way to express their sincere sorrow and grief while showing a modicum of virtuousness; a chance to thumb their noses at respectable folk through lavish displays of wealth (however ephemeral), simultaneously showing solidarity among their class and profession.

Laundry Queen, Lillian Powers (top left) and other women.

But camaraderie among the women of The Row had its limits. Violence among the women was common and the newspapers gleefully pounced on such incidents, taking the opportunity to provide social commentary about the type of women who lived among Denver’s demimonde—even as they reveled in the gruesome details of the attack. Following an incident in which a confrontation led to a woman being stabbed nine times by a fellow worker in June 1898, The Denver Post editorialized:

All these women are more than ordinarily disreputable and are said to be quarreling all the time with anybody who will quarrel with them. Like all other women of their class they have many names under which they live. Very little is known about where they came from or who they were once.

Suicide, too, was tragically common. The papers reported as many as two to three attempts at suicide every week. Unfortunately, many appear to have been successful. Morphine, laudanum, carbolic acid, and “Rough on Rats” (arsenic) were among the preferred methods for women who sought to take their own lives. One study of women working in brothels found eleven percent had attempted suicide at least one time. Isolation from family, hard living, addiction, money and legal woes, and untenable despair preyed on the women of The Row. A passage from The Denver Post of May 1915 captures this bleak outlook.

“Life is just one d[amned] thing after another and I’m tired of it all. It’s no use trying to be good. I’ve tried to kill myself twice with poison and couldn’t make it”….Eleanor Dacola, 21, inmate of a resort at 1923 Market Street, unburdened herself of the above sentiments this morning.…“I’ve tried to break away from the life I’ve been leading,” she said, “but it seems like it’s no use trying to be good. I went to business college last summer, with the intention of fitting myself to make a living in a decent way, but someone discovered that I had been living in a Market Street resort and that was the end of things. I’m discouraged, that’s all, and I don’t care what happens or when it happens.”

Substance abuse was common among the women who worked along The Row, especially those who had fallen to the bottom and ended their careers and lives working in cribs or on the street. Laudanum and morphine were cheap, legal, and available in drugstores. Opium was easily found in the nearby alley between Market and Blake Streets, between Nineteenth and Twentieth Streets—an area known by the derogatory nickname of Hop Alley. Drugs and alcohol offered a quick fix and a distraction from a dismal and often tedious life in the brothels, cribs, and streets.

The “well-upholstered” Mattie Silks, “Queen” of Denver’s Row.

Women working in the sex profession were, in their daily lives, vastly different from the way they were perceived and stereotyped, both at the time and more recently. From a poem titled, “On the Town,” the excerpt below is typical of the popular press’ fixation on the “wayward woman.” It was printed in Livingston, Montana’s Daily Enterprise in 1883:

Hated and shunned I walk the street,

Hunting–for what? For my prey, ‘tis said;

I look at it, though, in a different light;

For this night’s shame is my daily bread;

My food, my shelter, the clothes I wear!

Only for this I might starve or drown,

The world has disowned me–what can I do

But live and die on the town?

Newspaper accounts have always reflected and promoted the attitudes of the societies, and poems like this one reveal common assumptions about those working in the sex trade, casting them as objects of mockery, pity, intrigue, and tragedy. Reporters across the West commonly traded in stories that sensationalized, moralized, and vilified the experiences of women living in the shadows of polite society. Historians studying these important-but-marginalized women have almost always needed to rely on biased newspaper accounts to understand anything at all about the not-so-hidden world of sex workers..

A 1902 Denver Post headline blared “STRUGGLE FOR TWO CHILDREN: Mrs. Nina Moore Confesses to Leading a Life of Shame to Educate Her Children in Purity.” Nina Moore was deserted by her husband in Kansas City after he lit out for Telluride. Having therefore sued him for divorce on the grounds of desertion and cruelty, she was awarded custody of their two daughters. When she later arrived in Denver, she needed to support her children and her husband, Alexander, who eventually made his way to Denver and back into Nina’s life.

Her evenings she would spend in the said house on Market Street, and every evening the said Alexander T. Moore would take her over to the said house and leave her there, from which place she would return in the morning, in the early hours to her said home, and contribute her earnings thereby to the support of the said Alexander T. Moore and of their two children.

After so living in this manner for about five weeks, the said Nina E. Moore became worn out, and the struggle was too hard for her to keep up. During all of this time the said Alexander T. Moore had not procured any work, nor was he contributing anything to the support of either himself or her said children. Had he contributed anything to her support or the support of her children she would not have led the life she did lead, she was compelled to lead.

Nina’s story—of a woman’s life rocked by the economic disruption of desertion, in a tenuous position to care for her family—illustrates why some women turned to sex work for survival. These stories played out time and again in Denver’s parlor houses, brothels, and cribs. Nina represents just one of the many women whose lives had been marginalized and ignored, yet who were an integral part of Denver in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

A view of the 2100 block on Market Street in Denver, Colorado.

Spaces of Vice

Peering into the parlor houses and brothels of Denver, we gain a better sense of what life was like for the women within the different classes of the profession.

Parlor houses were distinctive for their generous, typically first-floor rooms, used for greetings and conversation before women and their guests would retire to bedrooms on the second and third floors. Some houses were elegantly and richly appointed, featuring banquet and billiard rooms, music and dance halls, and even ballrooms. An 1896 auction advertisement in the Rocky Mountain News describes the furnishings of a parlor house at 2148 Market Street, with its superb parlor suites upholstered in silk brocatelle and satin damask; a rich-toned upright piano; a fine music box; costly onyx and brass stands; brass easels and an elegant collection of paintings, etchings, and steels; and an elegant quarter-oak Windsor folding bed.

A parlor house could employ as many as twenty women, who were expected to be talented and attractive, and to lend an air of civility and class to the establishment. Houses would also employ servants, musicians, and a bouncer—sometimes himself a musician, referred to as “The Professor,” who was both entertainment and security. Wealthy patrons paid from thirty to one hundred dollars or more a night, and could expect well-dressed women in the latest styles ordered from the East or sewn by hired dressmakers.

Patrons were discerning, and would also expect good liquor. In Brides of the Multitude, historian Jeremy Agnew notes that spirits, fine wine, and champagne were crucial to parlor house profits and they were sold at huge mark-ups—as much as five or six times the wholesale cost. He describes champagne being sold at as much as thirty dollars per bottle, in a time when a miner only made three dollars per day and cowboys were making less than a dollar per day.

Dancing with plenty of high-kicks and leg shows, or music and singing by the women of the house would provide suitable entertainment for clients. Minnie Clifford kept a parlor house at 512 Holladay Street (which later became Market Street), where the cancan show was so infamous that it was featured in the National Police Gazette, a national tabloid newspaper, in 1880.

In this beautiful city of the West the devil is fast gaining ground. Drunkenness and prostitution are becoming alarmingly prevalent, and if not checked, will make Denver on a par with the worst cities in the Union in vice. The neighborhood of Halliday [sic] Street is the stronghold of sin. The stranger, no matter where he comes from, if his tendencies are evil, gravitates toward this locality as naturally as a duck takes to water. On this street are located the fashionable palaces of sin, the most notorious of which is presided over by Madam Minnie Clifford, who takes pride in saying that she is the only Madam in Denver in whose house the infamous dance known as the “Can Can” [sic] is performed. She openly boasts that her best patrons are married men, many of them bald-headed and grey, who frequently remain till three o’clock in the morning…Those who have seen these dances say that they excel in lewdness anything ever witnessed in this city. They are orgies which would delight the basest tastes.

Madams like Minnie Clifford paid all the expenses of running the house. They billed themselves as “landladies” who ran “female boarding houses” for propriety’s sake. The rooms were kept by the boarders who paid upwards of half their earnings back to the house, which covered room and board (possibly including the cost of their uniforms), laundry, security, and other domestic necessities. As such, they were perpetually in debt to the house’s madam. On the upside, unlike working on the street, parlor houses afforded women a relatively safe place to work where they didn’t have to dodge the police, thanks to madams who kept the law at bay with bribes and the means to pay off fines. In some of the better houses, women were paid a flat salary, in the neighborhood of $150 to $250 per week, compared to the $24 a month one might make as a seamstress. Madams were seen as shrewd business women who conducted financial transactions, negotiated legal agreements, hired and paid house staff, and were responsible for the overall management of the house.

Advertising the entertainments of the house was also part of the madam's job. She might pass out business cards and formal invitations to private events, in addition to arranging horse races, water fights, and public pillow fights between her boarders. Hiring marching bands to promote their houses, driving horse-drawn buggies to show off the newest boarders (always dressed in their finest), and hosting discount nights were other popular marketing events designed to spark interest in her business—in spite of ordinances prohibiting sex workers from driving, riding, or making an appearance on the city’s principal streets.

Though many may have preferred that the industry market itself more quietly, the spectacles were designed to be nearly impossible to miss. For example, in 1892, five enterprising madams were advertising the amenities of their establishments in A Reliable Directory of the Pleasure Resorts of Denver, also known as the Denver Red Book. Published to correspond with the national Knights Templar conclave held in Denver and the opening of the Brown Palace Hotel, it was a handy, pocket-sized guidebook to Market Street's many diversions. At 2015 Market Street, Jennie Holmes offered twenty-three rooms, three parlors, two ballrooms, fifteen boarders, and assured potential customers that they would find “everything correct.” Down the block at 1952 Market Street, Belle Birnard advertised twelve boarders, fourteen rooms, two parlors, and boasted that everything in her establishment was “strictly first class in every respect.” And next door, Minnie A. Hall’s house at 1950 Market Street boasted an impressive thirty rooms, five parlors, a Mikado Parlor (a room lavishly decorated in the Japanese style made popular by the Gilbert and Sullivan opera Mikado), twenty boarders, and bid a “cordial welcome to strangers.”

Historian Jeremy Agnew noted that madams were not usually active sex workers themselves, but were more often independent business women who owned and operated one or several houses—sometimes in partnership with investors. Mattie Silks maintained houses on Market Street for forty years. Friends described Mattie as “well-upholstered and an accomplished hell-raiser,” according to Clark Secrest’s Hell’s Belles. In a 1928 interview with a reporter from the Rocky Mountain News, Mattie said “I went into the sporting life for business reasons and for no other. It was a way for a woman in those days to make money, and I made it. I considered myself then and I do now—as a business woman.”

The allures of Market Street certainly attracted tourists and their money to the city. But madams themselves played a vital role in supporting the local economy through liquor and food purchases, as well as all of the other goods and services that came with running a well-appointed house. Profits from the sex trade also lined the city’s coffers with money for liquor licenses and fines in violation of running a disorderly house—while bribes to policemen and politicians helped keep their doors open. “Commercial sex was good for both the city and legitimate businesses,” Clark Secrest writes. He notes that economically, sex work was a source of income to the police, procurers, madams, doctors, politicians, and liquor interests, and goes on to say that the madams of Market Street maintained intimate and influential relationships with city fathers and municipal leaders. Whenever churches, schools, and other civic institutions found themselves in need, madams delivered their share of funding, considering it the cost of doing business.

But not all women on The Row worked in the luxurious surroundings afforded by madams like the “Queen” of Market Street, Mattie Silks. For every woman who worked in a parlor house, dozens more worked in the sometimes-seedy environs of a Market Street brothel.

“Brothel” is the general term for places where at least two gals hung out their shingles, indicating they were open for business. In the 1870s, the morally upright ladies of East Denver deemed the shingles so lewd that they attempted to eliminate such signs along Market Street. But according to local lore, the women of The Row responded with placards reading “Men Taken In and Done For.”

“Meretricious displays” were apparently quite effective at enticing customers along The Row, and newspapers teemed with reports of living window advertisements. Two French women, Miss Bertha and Miss Sarah, were arrested for making tawdry displays from the windows of their houses. In mid-March 1884, six women were charged with undue solicitation and meretricious display; the Rocky Mountain News reported that “Their offense consisted in keeping the curtains of the windows in front of their premises constantly raised and showing themselves gaudily dressed, after being repeatedly warned against the practices.” While the Denver Republican described a Market Street habitue arrested for the very dramatic meretricious display of wearing a “flaming red silk dress, red hat, red shoes and stockings, carrying a red fan and leading a poodle having been dyed red on a red leash.” French poodles were very popular with the Market Street set according to Clark Secrest, and were so identified with the filles de joie that no respectable woman would own one.

While the high-end parlor houses offered cozy companionship to erudite clientele, low-end brothels were more concerned with customer volume. According to historian Ruth Rosen, although descriptions are rare, middle-class brothels were common and were kept by women who represented the local population and served the average working man. She describes the women as having been born in America and “who had come from broken down farms and small ranches, some [of whom] had been deserted by railroad brakemen or boss carpenters who moved on, leaving them with no rent, money, or food.”

Such brothels were shabby and might charge by the quarter hour. Others used prepaid tokens or brass checks purchased from the lady of the house and then exchanged for services. Jeremy Agnew notes that much of the sex work in the West took place in these common brothels and cribs. Cribs were small one-or two-room shacks, sometimes squeezed in between larger establishments with the front door opening directly onto the street. Unlike working in a parlor house or brothel where the rent was paid by the proprietress of the house, albeit out of the wages of the women who worked there, women working in cribs were personally responsible for raising and paying rent directly to the owner of the crib. Although often squalid, crib rents were around fifteen to twenty-five dollars a week. In Denver’s Disorderly Women, historian Cheryl Siebert estimates that between 1870 and 1900 there were about six hundred women working as crib girls.

Dressed in low-necked, knee-length spangled dresses or loose-fitting, easily removed white Mother Hubbard gowns, crib girls would call from their doorways, “Come on in, dearie.” If that wasn’t enough enticement, they might snatch a gent’s hat and throw it into their crib, snagging a customer as he went in to fetch it. Women there sold companionship from twenty-five cents to two dollars an encounter—with an average of twenty or thirty customers a day. On a busy day, like payday for miners or cowhands who thronged to Denver to “see the elephant” in the slang of the day, a crib girl might have as many as fifty customers. Profit lay in volume and efficiency. Men lined up outside of cribs with their money in one hand and their hat in the other. Boots were kept on.

Madam Anna “Gouldie” Gould’s boarders lined up in front of a tapestry.

About ten percent of Denver’s sex workers were women of color. The Row was largely segregated, and the red-light district was home to brothels and “two-bit” houses that employed Black women who catered to both Black and white clientele. However, parlor houses and brothels in the white sections of the tenderloin did employ Black women as boarders and domestic workers. The red-light district, heartbreakingly, was also home to Chinese women whose families unwittingly contracted them to traffickers thinking they were sending their daughters to better lives and opportunities in the United States. Forced into indentured sex work, they were expected to sign contracts promising to sell their bodies until they paid off their debt for the cost of passage and boarding. Any days they couldn’t work—sick days, days of their menstrual cycles, and even pregnancy—were tacked on to their obligation.

Commercial sex work offered many women a means of survival and better wages than that of menial factory work or other low-wage occupations, but it also exposed them to physical risk and emotional strain. Brutality at the hands of customers was frequent, as was police harassment. Crib girls and low-end brothel workers were also more susceptible to illnesses like tuberculosis and malnutrition. Ruth Rosen points out that the squalor of their surroundings, combined with the quantity of customers women served, made working in common brothels and cribs an intolerable and debilitating experience. “Getting burned,” the slang for contracting a venereal infection, and pregnancy were risks of the profession. To avoid infection and pregnancy, women would douche between customers with mercuric cyanide, carbolic acid, or bichloride of mercury, all of which we now know to be highly toxic.

Cleaning Up The Row

The Row on Market Street would have been quite the scene in the late 1800s. The smell of stale booze and opium smoke wafted about, while the sounds of piano music, fighting, and gunshots echoed around the streets and alleyways. Scantily clad women called down to prospective customers—shocking passersby and affronting those trying to live on the straight and narrow path.

For the merchants, businesses, respectable boarding houses, and even family residences existing alongside the parlor houses, brothels, and cribs of Market Street, the sense of lawlessness led to demands to crack down on The Row. In fits and spurts, responding to public pressure, the city began attempting to impose some kind of order. Raids and mass arrests in houses of ill-repute began in the 1880s, but fines were a more common (and more lucrative) recourse. The City of Denver made more than a thousand dollars in January 1880 alone, much of that coming from the women keeping “lewd houses” and those who violated liquor licenses.

By the 1890s, at the urging of the city’s so-called respectable ladies, Denver issued an edict urging the women of The Row to wear yellow ribbons on their arms, lest they be mistaken for polite society’s women of upstanding moral virtue. In response, the madams and their girls dressed head to toe in eye-catching yellow costumes. And in an act of unity, they defiantly marched into restaurants and other public places where “respectable” folk gathered. The protest was effective and the rule was eventually repealed.

By the turn of the century, in March of 1908, District Attorney Stidger had enough of the brothels, and launched a raid on the cribs of The Row. As the Rocky Mountain News reported:

Wherever these fallen women and their masters go in Denver he [Stidger] will have them hunted down and arrested on the charge of vagrancy. If they seek refuge in lodging houses, the lodging houses giving them shelter will be treated as houses of prostitution, declares Stidger. As soon as anyone notifies him that women or men fleeing from the redlight district have taken refuge in other portions of the community, he will arrest them. And the town will be made so warm for them that they will be glad to leave.

Some women flocked to neighboring hotels. Some left town, going to ranches owned by friends, to Pueblo, or to Salt Lake—but many of the women were left penniless and without shelter when the cribs closed. Curious onlookers thronged Market Street to see the dispossessed women of the red-light district leave their homes and livelihood behind.

A group photograph of sex workers known as “Mamie's Darlings” that worked at 1959 Market Street in Denver, Colorado.

But the ladies of The Row wouldn’t be so easily displaced. It came as little surprise that the demand for sex workers was still as strong as ever, so it wasn’t long before many of the closed cribs and brothels came back or were reopened. Madam Mattie Silks purchased and operated the House of Mirrors in 1911, the most opulent of Market Street parlor houses, even while Denver Mayor Robert Speer was under pressure to do something about the cribs. In 1912, the Mayor ordered the cribs along The Row torn down. Some sources say that The Row was “effectively” closed between 1914 and 1915, and in 1918 the US Army was brought in to completely shutter Market Street. Most of the parlor houses, brothels, and saloons were razed or repurposed as warehouses,and nearly 300 women found themselves without means of support. Perhaps it comes as little surprise that, as reform movements gained momentum, the circumstances that led women to choose sex work over the limited choices of more respectable occupations were not magically resolved. Sex work in Denver never was eradicated; it just moved to other areas of the city, operating clandestinely out of private homes and hotels or openly along other thoroughfares of the city.

Stories Echoing from the Past

The women of Denver’s Row represent a microcosm of nineteenth-century American society. It flourished with its own values, class structure, political economy, and cultural and social relations. While violence, dispair, and death stalked the women of The Row, sex work afforded them a chance at financial and personal independence when few options or opportunities existed.

Although hidden in the shadows of Western history, their stories are no less important than those more popularly documented. In the women of The Row, we recognize struggle, empathy, and humanity resonating across the divides of class and time. Looking back at their lives, we see people who helped build the city and create its character. Their marginalization and relative silence in the historical record tells us as much about the times they lived in as those who have dismissed their stories as unimportant or sensational ever since. But by recognizing their humanity and understanding their circumstances free from the moralizing judgements that have been levied against them, we find these women of Denver, and their stories, worthy of remembrance.