Story

Mesa Verde: First Official Visit to the Cliff Dwellings

William Henry Jackson’s early photographs documented Colorado in a way few had ever seen on film. His work with the US Geological Survey in the late 1800s made him one of North America’s most accomplished explorers, and his work is still famous today. This article is a narrative of the trip that produced the first photographs of Mesa Verde. It was originally published in 1924.

The Photographic Division was outfitted as a separate unit of the U. S. Geological Survey of 1874, the same as the year before, and, in starting out from Denver the 21st of July, was instructed by Dr. Hayden to proceed first to Middle Park via Berthoud Pass and then to work south, crossing the head of the Arkansas to the San Luis Valley and thence to the San Juan Mountain region. Our itinerary had been talked over and changed many times before our plans took definite shape, the underlying purpose being that we should traverse some portion of the territory of the other divisions of the Survey. Wilson had been assigned the southern or San Juan region and, on account of its reputed wonderful mountain scenery, I was expected to co-operate more fully with him and make this the main objective of my season's work. The near half century that has passed since then has obscured my memory as to some details, but I am very certain there was no intention to go south of Baker's Park into the San Juan basin until we met Cooper and his outfit near the head of the Rio Grande on his way into that country.

Having worked over most of the territory assigned to us we finally reached the Rio Grande on our way into the heart of the "San Juan" via Cunningham Pass. On the 27th of August we camped early in the day at Jennison's (Chemiso) Ranch, as it was too late to make the Pass that day, and also to do some photographing in the neighborhood. Another and equally potent inducement to stop was the opportunity to get a good square meal served by the rather attractive young hostess of the ranch, as we were almost out of "grub" and no more to be had until we reached Howardsville.

While we were unpacking, a burro pack train came along and went into camp near by. As they passed us there was much hilarity over the very comical appearance of one of the party, who was astride a very small burro, with another one of the party following behind with a club with which he was belaboring the little jack to keep him up with the train. On our return to camp from our photographing later in the day this same man had come over to visit us. A mutual recognition followed our meeting as I remembered him as a fellow townsman in Omaha when I was in business there a few years previously. With all of us grouped around a rousing big fire after supper we talked long into the night, Tom Cooper explaining that he was one of a small party of miners working some placers over on the La Plata, that he had been out of supplies and was now on his return to their camp. As he appeared to be well acquainted with this part of the country, we "pumped" him for all the information he could impart. As he was naturally a loquacious individual, he had a great deal to say, and, understanding in a general way the object of our expedition, urged us by all means to come over to the La Plata and he would undertake to show us something worth while.

It was generally known that many old ruins were scattered all over the southwest, from the Rio Grande to the Colorado, but Cooper maintained that around the Mesa Verde, only a short distance from their camp, were cliff dwellings and other ruins more remarkable than any yet discovered. All this interested us so much that, before we “turned in" that night, we had decided to follow him over to his camp as soon as we could outfit for the trip.

Cooper had not traveled over the country where the most important of these ruins were to be found but had his information largely from John Moss and his associates. Moss, he explained, was the high "muck-a-muck" or "hi-yas-ti-yee" of the La Plata region, who, through his personal influence with the Indians, had secured immunity from trouble not only for his own operations but also for others traveling through the country.

A few days later, after dividing our party in Baker's Park and traveling light, just Mr. Ingersoll and myself with the two packers, we were on our way to the La Plata. Soon after leaving Animas Park we overtook and passed Cooper's outfit and a few miles farther on were very much surprised by the appearance of Moss himself coming up from behind on a jog trot with the evident purpose of overtaking us. Riding along together until we reached camp, cordial relations were established very soon, and, with a good deal of preliminary information, he promised us his co-operation, and possibly his company, in our further operations.

Moss at this time appeared to be about 35, of slender, wiry figure, rather good looking, with long dark hair falling over his shoulders, and as careless in his dress as any prospector or miner. Quiet and reserved in speech and manner generally, he warmed up to good natured cordiality on closer acquaintance, and, as we found out later, was a very agreeable camp companion. Jogging along together over the trail, he described in a general way what we might find, the natural features of the country and the difficulties to be met with. He also had a good deal to say about a recent treaty with the Southern Utes, by which new boundary lines had been established excluding them from the mountain regions, very much to their dissatisfaction, not only on account of the loss of their hunting grounds, but also because of the failure of the government so far to make some promised awards. As one of the consequences they were frequently ordering all white men off their former reservation, and, while there was but little actual hostility, there was a good deal of uncertainty and apprehension. Moss explained that when he first came into this country he had made a treaty of his own with the principal chiefs, and, by the payment of a liberal annuity in sheep and some other things, had secured their good will and freedom from molestation in their mining operation.

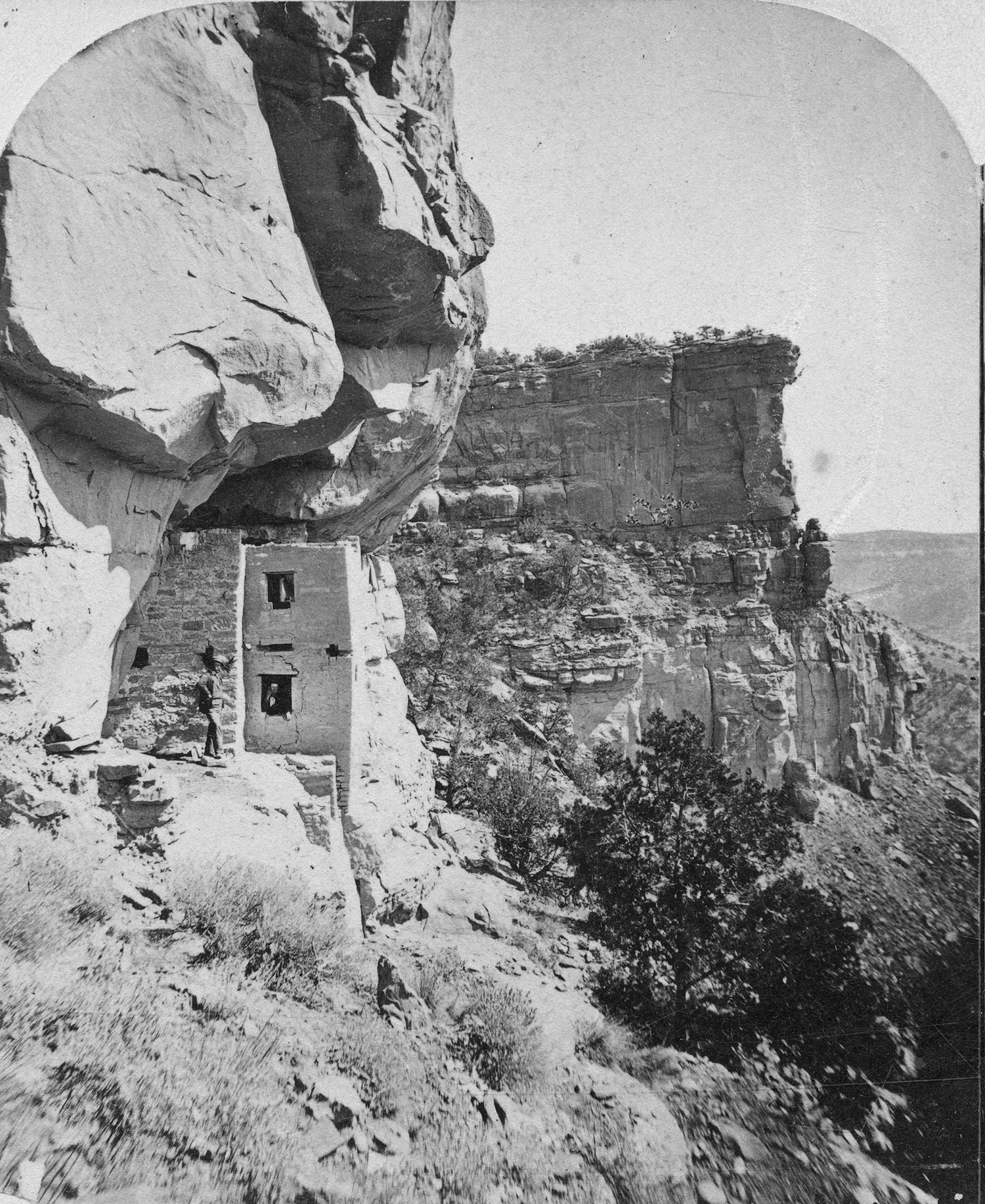

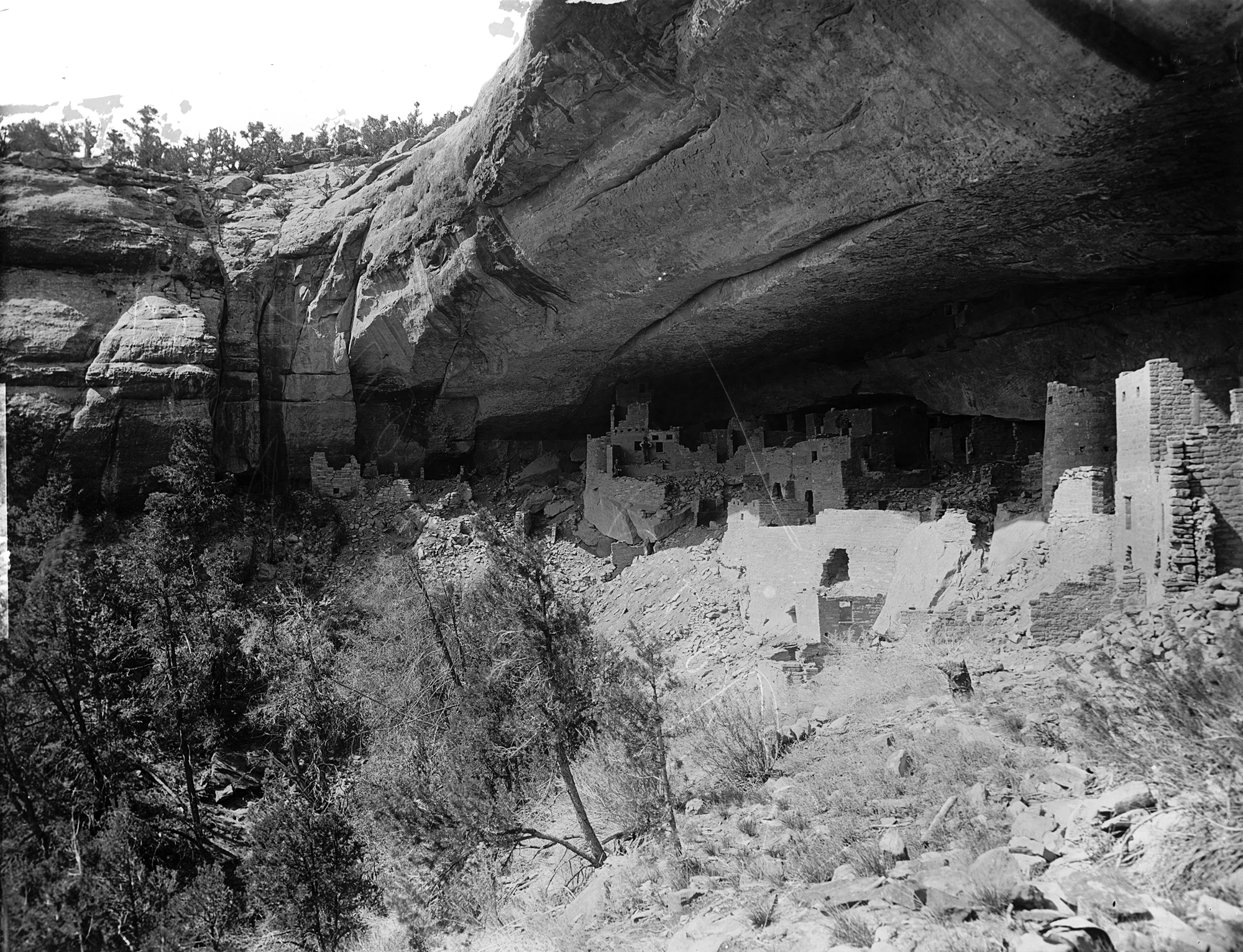

The Mesa Verde Cliff Palace, photographed by William Henry Jackson in 1874.

So far, I have drawn largely upon memory in relating the incidents that directed my attention to archaeological, instead of scenic, photography on this San Juan expedition. I intended leaving the story at this point, but, in looking over my old notes again in an effort to revive recollection of almost forgotten details, I find some descriptions of personal experiences that, I think, will bear repeating.

"Sept. 9th to 15th, inclusive, was occupied with the investigation of the Cliff ruins, all of which is set forth fully in the Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Surveys, Vol. 1, 1874-5. The following notes will omit the details of these investigations, and will mention only a few incidents in the day to day happenings of, to us, a very eventful week.

"I have already mentioned, in my daily notes, the composition of our party up to the time we reached the La Plata camp, but I will bring the different members together again, at Merritt's Ranch, as made up for this occasion, all eagerly expectant as to possible discoveries, and alert with the spice of adventure because of the uncertain temper of the more unruly Indians who frequent these remote canyons. When we started out this bright and bracing September morning we had as guide and mentor Capt. John Moss, a small wiry man of about 35, as hardy and tough as an Indian, quiet, reserved and even tempered, helpful and resourceful in all that pertains to life in the open—his knowledge of the country and of its little bands of aborigines was of great service in many ways. Cooper came with us, not that he will be of much help, but because of former friendship and that he was the means of bringing us to the La Plata camp and the acquaintance of John Moss. He was an easy going chap, somewhat indolent and content to follow along with the packs—very loquacious and full of wonderful stories concerning himself—supplying most of the amusement in the banter around the camp fire after the day 's work was over. Ingersol and myself with the two packers, represented the Survey. We had three pack mules, 'Mexico' carrying the photographic outfit--a little rat of a mule but a good climber, and could jog along at a lively pace without unduly shaking up the bottles and plates. 'Muggins' and 'Kitty' carried the 'grub' and blankets, and as both were reduced to bare necessities, their packs were light and they could be pushed along as fast as we cared to ride. Steve and Bob with their packs kept close to the trail most of the time, while the rest of us were roaming all over, investigating every indication of possible ruins that came to our notice; and when photographing was decided upon, 'Mexico ' would be dropped out, unpacked, tent set up, and the views made while the others jogged along until we overtook them again.

Looking out from the Cliff Palace over the canyon. Photo by William Henry Jackson, 1874.

"Our first discovery of a Cliff House that came up to our expectations was made late in the evening of the first day out from Merrit's. We had finished our evening meal of bacon, fresh baked bread and coffee and were standing around the sage brush fire enjoying its genial warmth, with the contented and good natured mood that usually follows a good supper after a day of hard work, and were in a humor to be merry. Looking up at the walls of the canyon that towered above us some 800 to 1,000 feet we commenced bantering Steve, who was a big heavy fellow, about the possibility of having to help carry the boxes up to the top to photograph some ruins up there--with no thought that any were in sight. He asked Moss to point out the particular ruin we had in view; the Captain indicated the highest part of the wall at random. 'Yes,' said Steve, 'I can see it,' and sure enough, on closer observation, there was something that looked like a house sandwiched between the strata of the sandstones very near the top. Forgetting the fatigue of the day's work, all hands started out at once to investigate. The first part of the ascent was easy enough, but the upper portion was a perpendicular wall of some 200 feet, and half way up, the cave-like shelf, on which was the little house. Before we had reached the foot of this last cliff only Ingersoll and I remained, the others having seen all they cared for, realizing they would have to do it all over in the morning. It was growing dark, but I wanted to see all there was of it, in order to plan my work for the next day, and Ingersoll remained with me. We were 'stumped' for a while in making that last hundred feet, but with the aid of an old dead tree and the remains of some ancient foot holds, we finally reached the

bench or platform on which was perched, like a swallow's nest, the 'Two Story House' of our first photograph. From this height we had a glorious view over the surrounding canyon walls, while far below our camp fire glimmered in the deepening shadows like a far away little red star.

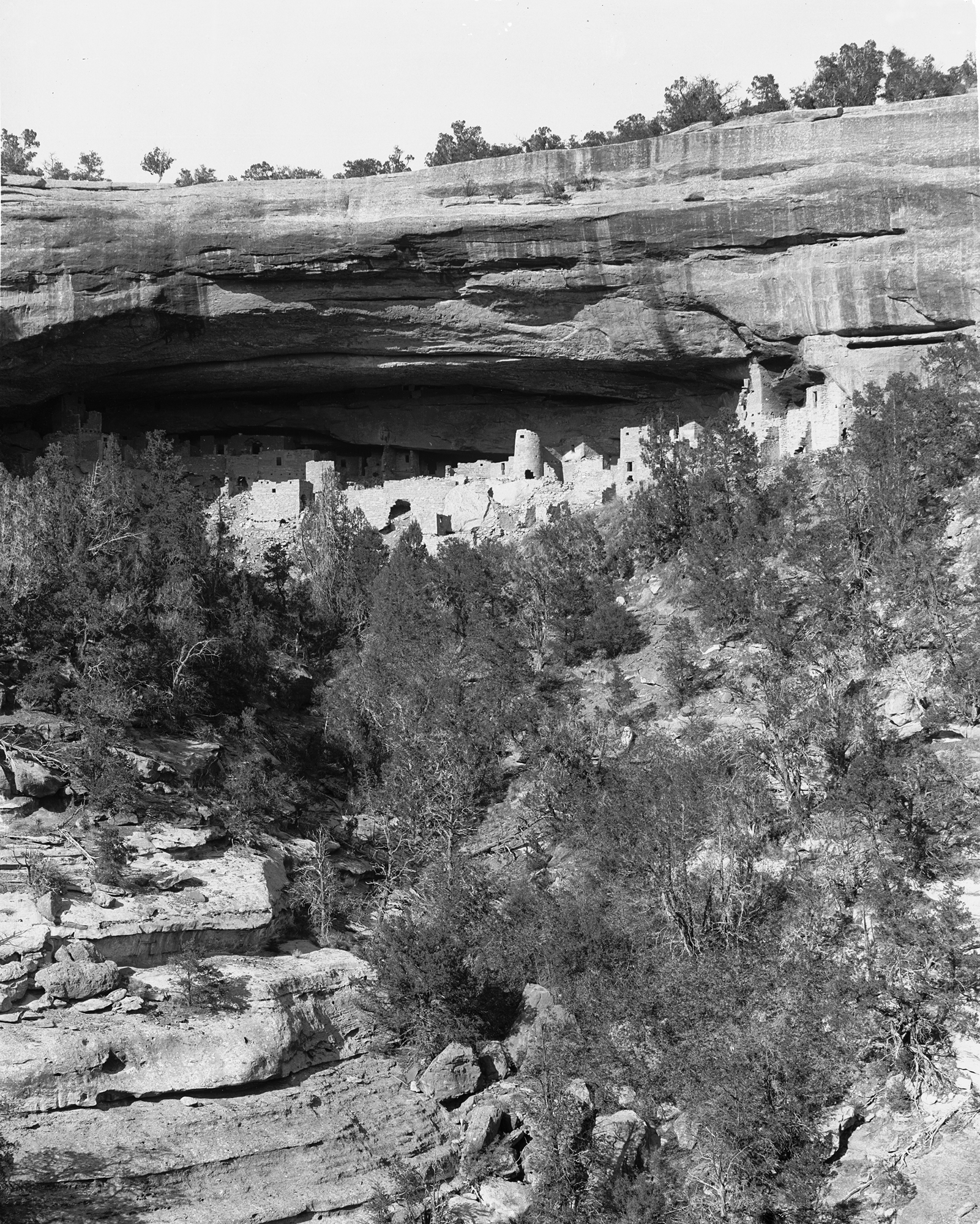

Cliff Palace from across the canyon. Photo by William Henry Jackson, 1874.

"As everyone took a hand in the camp work we were generally off on the trail quite early, not later than sun up, each morning, and were able to make fast time and good distances, despite the many diversions to investigate and photograph, but on the fourth morning out, on the head of the McElmo, we got a late start, with a long ride ahead, where it would have been much better to have made the greater part of it in the cooler hours of early morning. It was all owing to the wanderings of our animals. Generally they were tired enough to remain near camp when there was water or any kind of feed. If likely to wander, we hobbled, or staked out, the one or more that were leaders. Whenever we could trust them, however, we preferred to do so, for it was but a scanty picking they got at the best, and we liked to give them all freedom possible. So this morning at Pegasus Spring, with the prospect before us of a long ride under a hot desert sun, we had breakfast dispatched before sunrise, and while the rest of us packed up, Steve went out to bring up the stock which was supposed to be following the strip of moisture and scanty grass in the bed of the wash below us. Our work was soon done, but no mules appeared. Finally after an hour's impatient waiting, we saw Steve coming up in the far distance, accompanied by an Indian but without the animals. Cap. and I ran down to meet them; Steve reported that he had been unable to find any of the band, but the Indian, who said he was the father of the 'Captain of the Weemenuches,' was of the opinion that our man did not know how to follow trail, and that our animals had left this valley and gone up a left-hand branch leading back to the mountains. Moss understood Ute well enough to get all the information we wanted, and also, that there was a small band of Indians camped below. Perhaps they had something to do with the disappearance of the stock in the hope that some stragglers might be picked up later, but we accepted his protestations of good faith and sent him up to our camp, while Cap. and I struck out at once to pick up the trail. A mile below we found where it turned off to the right. High up on the top of the mesas we heard Indians calling, or signalling one another, in the long drawn out highly pitched key peculiar to them, but what it all meant we did not know. Keeping up a jog trot, or run, as fast as our wind and endurance permitted, we finally came out on a low divide where we met a couple of young bucks mounted and loaded down with skins. They were on their way to the Navaho country and intended stopping at the spring where we were camped. If we did not succeed in finding our stock they would assist us after they had had a rest. We trotted on, however, keeping up, a stiff pace, passing the five mile spring, and then coming to a big bend in the trail, I followed around while Capt. cut across, and there, where we met, at the foot of the last hill leading up the Mancos divide, we found the animals all grouped together under a tree, whisking their tails in contented indolence. Mounting bare back, with lariat ropes for bridles, we took a bee line for camp, and pushing them along at a stiff pace, were back to the spring by ten o'clock. Found the camp full of Indians, all mounted, the Captain himself among them, a venerable, gray headed, old man. Most of the others, with the exception of the one we met with Steve, were young bucks bound for the Navaho country. Were all quietly good natured and did but little begging. The old Captain wanted to know what we were doing down here, and when our business was explained to him by Moss, all of them laughed most hilariously, not comprehending what there could be in these old stone heaps to be of such interest.

"It was intended to reach the western limit of our explorations this day, on the banks of the Hovenweep, so we had a long drive before us, under an exceedingly hot sun blazing down into the dry and barren wash of the McElmo. We pushed right through on the double quick, deferring all photographic work until our return, but investigating and noting everything of interest as we traveled along. We made only one stop, and that for water, late in the afternoon, at a point where we left the McElmo to cut across the mesas to the Hovenweep. Water was expected to be found here, but the bed of the wash seemed perfectly dry, as it had been all day since leaving the spring. Water we must have, so we got busy and with a shovel that we had with us, dug down in the sand to about four feet, when water began to trickle slowly through, but the sand caved in so fast we could not get much of a pool. After a drink around ourselves, we filled our hats, a cup full at a time, and gave our animals a taste at least. They stood around whimpering in eager expectancy, and apparently appreciated our efforts to help them.

"On the return trip from the Hovenweep, we were three days getting back to the La Plata. It was a busy time with a good deal of photographing and some digging about the ruins. On the way from Pegasus Spring to the Mancos, Ingersoll got interested in some fossils and fell behind some distance. When he came out on the broad open divide between the Dolores and the San Juan, he failed to pick up our trail and went off on another that led over into Lost Canyon. He was lost for good nearly all night, but by taking the back track managed to rejoin us at Merrit's soon after sun rise.

"Remained long enough at the Mancos to make some negatives of the ranch house and then 'lit out' for the La Plata at top speed, getting there just in time for dinner before dark. The miners have all moved down from the upper camp, and are just starting a new one for the winter, the ditch having been brought down to this point.

"Sept. 16th, off for Baker's Park again, after a very cordial leave-taking all around. Made many plans for the continuation of our work next year. Found Animas Park almost entirely deserted and farms abandoned because of the 'Indian scare.' Took this opportunity to load up with fruit and vegetables, as our supplies were at the vanishing point."