Story

Disregarded Disability

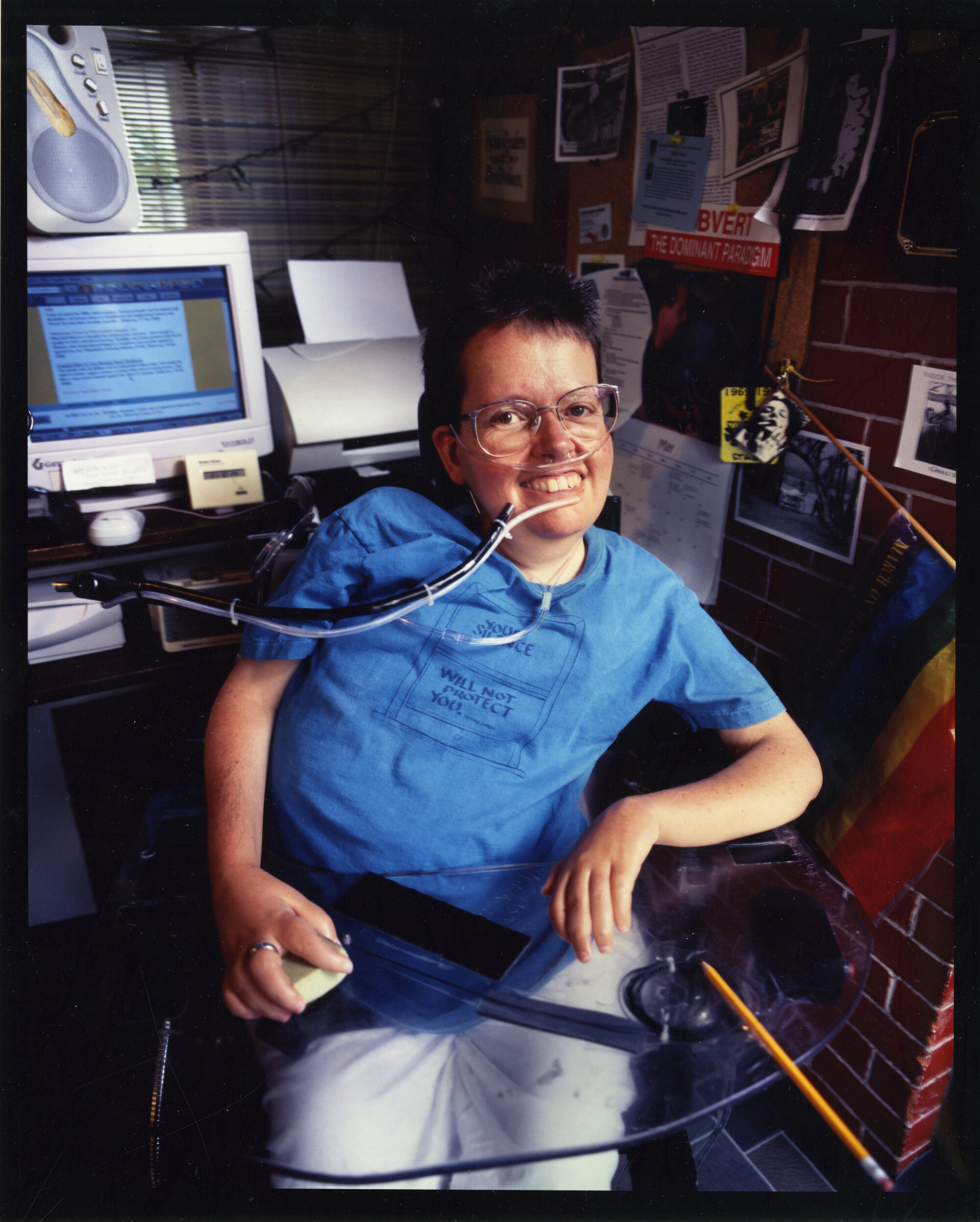

Laura Hershey’s lifelong fight to unite the goals of activist movements in Colorado.

Editor's note: This article was adapted by the author for The Colorado Magazine from an essay submitted to the Emerging Historians Contest.

Laura Hershey grew up an activist.

She was born in 1962, during the era when Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains rallied around the new birth control pill and reproductive rights. She entered kindergarten when the Black Panther Party was leading Denver’s civil rights movement and first grade as the Chicano Movement officially organized in the city. Laura’s mother Faye, a member of the Colorado branch of the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), dedicated herself to advocating for people with disabilities in Colorado. In one speech, Faye praised her daughter’s strong spirit, recalling a conversation in which Laura said she wanted to fight for equality for women and other disadvantaged people. Her mother reminded her, “Surely, you will fight for the rights for people with disabilities.” Laura responded, “Oh, of course, I forgot!”

As a child diagnosed with Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Laura used a wheelchair from a young age. Her diagnosis led to some early experiences of disability discrimination, and to her mother’s association with the MDA.

Her life encapsulates the complications of connectivity, intersectionality, and individualism in activism during the late twentieth century. Feminism and the women’s health movement were prominent during her life, with health clinics, books, and tribunals active all over the Front Range. Disability rights activism also found its footing during this time, with one of the most prominent movements in the country happening in Denver. But while these two types of groups shared many goals, such as bodily autonomy, reproductive justice, and respect in healthcare, the larger feminist movement often denied representation and participation for women with disabilities. Later in life, despite Laura’s increasingly expansive resume as an accomplished writer, poet, and activist, she sometimes found herself stigmatized in various movements because of her identity as a woman with a disability.

This was an experience shared by many. Even as the women’s health movement gained strength in Colorado, its goals and attitudes sometimes overlooked the inclusion of women with disabilities, who were often forced to fight from the platform of disability, rather than feminism.

Poster Child

Laura experienced the stigma of disability early at her primary school in Littleton. Children with cognitive and physical disabilities were then often placed in schools exclusively for children with disabilities. A frustrated Laura was one of them. Laura recalled the environment as stifling and disempowering. Inadequate staff and resources caused a lack of structure. Upon embracing disability activism in her adulthood, she fought to end this type of segregation.

At a young age she became a literal poster child for muscular dystrophy. Her mother was also known to attend and speak at MDA events. Four years after Laura was born, the MDA Labor Day Telethon premiered in the United States. The annual broadcast, hosted by Jerry Lewis, was designed to raise awareness and fundraise for children with muscular dystrophy nationwide.

Children who participated in the weekend telethon were even given the nickname “Jerry’s Kids,” in an effort to portray him as a fatherly figure. The telethon gained national attention, especially with Lewis’s tactic of using children with muscular dystrophy to raise viewership. However, by the 1970s, disability rights activists began organizing against Jerry Lewis. These activists argued that the telethon further stigmatized disability by engendering pity for the MDA youth. Whether or not Laura was initially proud to be representing this large organization is unclear, but she plainly grew to disdain Jerry Lewis and the MDA Labor Day Telethon.

By the time Laura was thirty, she was helping to lead Denver’s protests against the Jerry Lewis Telethon. Activists argued the telethon exploited children with muscular dystrophy more than it actually helped, and Laura became angered by its manipulative nature. Despite the fact that “two-thirds of MDA clients are adults,” Laura wrote, “as adults, we need respect, equal rights, and access to jobs, transportation, and public places. Those things become harder to get, when the rest of society is being fed such a negative view of people who have muscular dystrophy and other disabilities.” Laura led protests in Denver and wrote regular blog posts criticizing the telethon.

Activists demanded equal rights and accessibility and rejected notions of pity; in fact, a draft flier for MDA protests read: “Respect, not pity… Pity kills!” In a later interview, Laura recalled with disgust that Lewis had been upset with the protesters because he had bought them all wheelchairs and felt they should have felt more grateful. Laura disputed this claim and condemned how he presented himself as a savior to children with disabilities while ignoring the disease in adults.

Pity for women with disabilities created a clear and often tense divide between them and the feminist activists in the women’s health movement who were sometimes viewed as creating an idealized image of women in their fight for equality and reproductive rights. Their movement championed the narrative that women were strong, independent, and capable of making their own decisions about their bodies. In contrast, individuals with disabilities, and especially women, were stereotypically portrayed as weak and dependent. Laura’s experience with segregation, pity, and inadequate social services would inspire her to use her skills as a writer and activist to fight for women with disabilities around the world.

The Women’s Health Movement in Colorado

In Colorado, reproductive health campaigns sometimes were couched in terms that stigmatized disability. Campaigns promoting birth control might, for example, suggest that avoiding motherhood could benefit community health. As early as 1966, the Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains discussed birth control as a way to prevent offspring with cognitive disabilities. The organization hosted panels addressing the dangers of overpopulation, headlined by prominent community members, such as pastors, scientists, and politicians, who warned that species cannot thrive in tight quarters and how overcrowding may result in mental illness. Following one panel, a local paper speculated about solutions to this issue, writing “Should a segment of the population be sterilized? Should people prevent the birth of children who would be born defective?”

Politicians and Planned Parenthood leadership had long believed that birth control could help prevent poverty by giving low-income women strategies and resources to prevent children they did not want or could not afford to have. The stated goals of the women’s health movement were to empower all women to make their own choices by giving access to birth control and sex education; however, these goals were still mediated by their suggestions of stigma surrounding disability.

The passage of the 1967 abortion law in Colorado was groundbreaking nationwide, but many disability activists felt that it was used as justification only to abort disabled fetuses. While this is not to say that disability activists were anti-abortion (Laura Hershey and many of her colleagues were vehemently pro-choice) questions surrounding disability rights complicated the issue and created enduring controversy around the ethics of prenatal testing.

Laura grew up during the era of informed consent and witnessed its role in women’s health. As she later wrote, women with disabilities experienced the same discriminatory medical practices as other women without disabilities, but this experience was magnified by their disabilities. Disability activists endured a centuries-long struggle to undo the perception of disease on the disabled body. The stigma of disability as a medical ailment that needed to be cured often resulted in medical malpractice for misdiagnosis.

Women were not the only people demanding respect from their physicians. Historically it was common for patients to avoid asking questions or making any medical decisions that went against their doctor. As a result, many people found themselves mis-diagnosed or mistreated by their physicians and felt powerless to do anything about it. In the 1970s informed consent passed into law, spurring many different activist groups to add equality in healthcare to their agenda. However, while these groups were advocating for similar rights, they were not all willing to join forces.

The women’s health movement of the late twentieth century rose from a dire need to change a patriarchal healthcare system. Women were often patronized in the doctor’s office and in many cases were given little information about what was going on in their bodies. Abortion was illegal and black-market abortions were expensive and often unsafe. Effective birth control was also hard to come by, but even when it was available it could cause detrimental—and sometimes fatal—side effects.

One in a series of cartoons produced by the COPOH in a pamphlet titled “Focus On: Disabled Women.” The pamphlet highlighted common myths and beliefs about women with disabilities, including sexuality, health, and reproduction.

Disrespect in the medical setting is now seen to have often translated to a general disregard towards sexual abuse against women. One woman recalled her first visit to a health clinic as an adult, seeing a poster on the wall that shockingly read “You rape ‘em, we scrape ‘em.” The ignorance towards sexual abuse was a nationwide phenomenon. Several states did not view marital rape as a crime, Colorado included.

In 1967, Colorado became one of the first states to decriminalize abortion. Women could now have legal abortions in cases of incest, rape, and medical complications of the mother or child. However, decriminalization was a far cry from full legality and many doctors refused to perform abortions on moral or political grounds.

In the early 1970s, women from many states including Colorado partnered to form an affiliate of the Women’s National Abortion Action Coalition. These women traveled across Colorado raising awareness for women’s health rights, especially access to abortion and contraceptives, and championing an end to forced sterilization. The coalition provided referral services for healthcare and abortion clinics and hosted tribunals including an organized debate with the Colorado branch of Right to Life. Under the title “Crimes Against Women,” these tribunals vocalized their complaints against the medical patriarchy. Other activist groups followed suit, and soon began to advocate for other causes, such as sexual assault awareness and resource centers for abused women.

Over time the movement became increasingly intersectional and multifaceted. High- profile violations of the rights of women of color, such as the 1973 sterilization of the underaged Relf sisters, forced women’s health activists to grapple with issues of race and how women of color were disproportionately affected.

In the 1970s, the women’s health movement expanded on federal efforts to create neighborhood health clinics and began building Feminist Women Health Clinics. In Colorado, the first such clinic opened in Colorado Springs in 1972. These clinics were instrumental in the dispersal of sexual health education. They taught women the revolutionary practices of self-examination which helped women identify abnormalities, infections, and pregnancy, and encouraged knowledge about their bodies to erase the obfuscation that had plagued women’s health.

This is the environment in which Laura Hershey grew up: women protesting on the streets, holding tribunals, lobbying local governments, and constructing healthcare facilities and educational programs in an attempt to disrupt the patriarchal medical hierarchy and demedicalize the female body. Perhaps the most influential component of the movement to Laura was literature. Feminist publications were at their peak during her lifetime, and this influenced her own writing, which featured profound discussions on feminist theory and the female body. Demystification of the female body was a rallying point for the women’s health movement, for Laura, and the disability rights movement that she would champion.

Laura’s Activism

Laura Hershey’s work would come to embody the diversity of social movements. She was a disabled lesbian woman dedicated to advocating for all. Despite her fight to advocate for women, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ people, she believed that none of the movements were doing enough to work together. She believed that it was due time for both the feminist movements and disability movements to adopt a “women-centered view of disability,” because both movements had yet to focus on the reproductive health of women with disabilities. Laura would often cite the goals of the women’s movement and relate them to goals of the disability movement, inspiring her to create spaces for their intersection.

Laura’s research in adulthood included analysis, mental health, and activism in the deinstitutionalization of women with disabilities. The deinstitutionalization movement in the United States began in the 1950s as an effort to create alternative care methods for people with cognitive and physical abilities. However, the stigma of disability continued. During Laura’s lifetime, women with disabilities were often institutionalized in nursing homes with poor care and little independence. The Independent Living (IL) Movement became a platform for people with disabilities to demand adequate healthcare and general independence in their day-to-day lives.

In Denver, the IL Movement gained traction starting in the 1970s. The movement was geared towards the deinstitutionalization of people of all ages in nursing homes and creating more independent living communities. At state conferences for women with disabilities, Laura discussed how nursing homes reversed the progress of liberation and claimed that “with institutionalization, women with disabilities lose almost any chance for a satisfactory life.” She advocated for alternative forms of care, including expanding community care and independent living programs in the state.

The social stigma surrounding women with disabilities made them more susceptible to institutionalization. Laura recognized that women like her were doubly marginalized, both as women and as people with disabilities. Second-wave feminists challenged psychiatric diagnosis when they did not adhere to traditional female roles, like being mothers. However, in the case of women with disabilities, society viewed them as incapable of filling those traditional roles despite attempts and desires to do so.

Beyond institutionalization and reproductive control, women faced the social constructs surrounding motherhood. Women with disabilities viewed reproductive rights more broadly than mainline feminist activists. To them, it wasn’t just about the right to not have a child, but also, in the words of disability rights scholars Virginia Kallianes and Phyllis Rubenfled, to be “seen as ‘fit to mother’ and to refuse the use of genetic technologies.” Social constructs of womanhood often meant that much of society did not view women with disabilities as fit for motherhood, which is most clearly seen in the barriers to adopting children

Laura’s poem “Fertility Goddess” portrays the unjust adoption system, and how she and her partner Robin, as wheelchair users, were on the receiving end of discrimination because they did not fit the ideal vision of motherhood. “Our hearts were broken,” Hershey wrote, “our power wasted by a system that would rather bar its door to us than find a child a home.” During Laura’s career as an activist, at least one unnamed woman with disabilities from Denver had her child taken from her because of her disability. Even beyond providing or denying healthcare, society maintained control of reproduction and parenthood for people with disabilities. As Laura explored further in “Fertility Goddess”, because these women were unable to “rescue [kids] from fires,” or “their soiled beds”, wheelchair users were oftentimes deemed unsuitable to supervise children.

Photo of Laura Hershey and fellow activists participating in the Portland LGBTQ Pride Parade, 1999.

One of the issues facing women with disabilities is that they have historically been treated as “socially genderless,” relegating them to a different category than women without disabilities. As one activist observed, “I don’t get to be sexualized.” She noted that the typical perception of women as “sexy” was never applied to women with disabilities, perpetuating the belief that women with disabilities could not and should not have sex. This divide resulted in a general inequalities in sexual healthcare services, including a lack of sex education, restricted access to contraception, forced abortions and sterilizations, discouragement of bearing children, and losing custody of children.

The belief that women with disabilities should not be having sex permeated social perceptions of motherhood. People often viewed it as a crime for women to carry a child they knew to have a disability, and likewise for them to willingly bear children. Women with a disability getting pregnant, or passing down a disability when genetic testing and abortions were available, led to demonization. Activists consistently fought this narrative, claiming that most of the barriers they faced becoming parents were due to negative societal perceptions surrounding disability and physical barriers to adequate care.

Another consequence of desexualization of women with disabilities is that they have historically been victims of sexual abuse at higher rates than women without disabilities. Despite this, they were not receiving protection or representation within the women’s health movement. And, as Laura pointed out, sexual abuse often creates more health problems for women.

Laura’s observations regarding sexual abuse were made at a time when Denver was launching anti-sexual assault campaigns during the women’s health movement, citing sexual freedoms. Some sources reported Denver as the rape capital of the world, with the highest incidence of reported sexual assault against women during the 1970s. Resources like homes and call centers popped up all over the city to assist women; however, these resources did not address people without disabilities despite their higher rate of abuse.

Laura recognized these unaddressed parallels early on in her career as a disability rights activist. In 1985, activist Sharon Hickman founded the Denver branch of Handicapped Organized Women (HOW), with which Laura became an active leader. These women designed HOW to be an organization in Denver where women with disabilities could examine “what the women’s movement means to women with disabilities.” While the group did address multiple facets of disability, like transportation, their work centered around safety for women with disabilities.

Hickman realized that although Colorado had ample resources for victims of domestic, sexual, and caregiver abuse, women with disabilities did not have the same access to those programs. As HOW recognized, the women’s movement had highlighted the dangers women faced, but now it was their initiative to shed light on how this impacted women with disabilities.

Laura was an active participant in creating the Domestic Violence Initiative. With her advocacy, she won a large federal grant which enabled the Initiative to get on its feet. Sharon Hickman credited Laura as “instrumental in bringing this issue to the forefront” of the disability rights movement.

Laura and Sharon continued to work together for the health of women with disabilities throughout their careers. In 1985, the two prepared a lecture on women and disability for Colorado College, Laura’s alma mater. With dozens of women in attendance, the conference discussed disability rights issues for women. These included reproductive rights, healthcare access, institutionalization, and sexual assault. And as recently as 1999, Laura Hershey was still bringing awareness to the eugenic nature of prenatal testing for disabilities. She warned against the Human Genome Project and the normalization of screening for disability. As a pro-choice feminist, she argued that prenatal testing was not about women’s reproductive rights but instead “about pressuring women to carry out public policies which are driven by scarcity economics, utilitarianism, and deep-seated social prejudice against people with disabilities… and stigmatizing women who do bear children who have disabilities.”

By bringing these issues, and the intersections between them, to the forefront through her writings, conferences, and organizations, Laura created a place for women to talk, learn, and practice activism in Colorado.

Still Searching for Belonging

Laura Hershey once confided to a friend that although she identified as LGBTQ+ and was an outspoken LGBTQ+ rights activist, ableism and inaccessibility still prevented her from feeling like she belonged. This confession reveals further exclusivity within social movements towards disability.

The women’s health movement has been scrutinized by scholars as a movement of white, middle-class women. This has inspired scholars of the movement to discuss women of color and how they fit into the larger movement. These women often faced additional health concerns compared to white women. Historically, Native American, Puerto Rican, Black, Latina, and immigrant women were more often victims of forced sterilizations and racism in medical settings. But the women’s health movement did not just exclude women of color, it also excluded and overlooked women with disabilities and their health concerns despite the rising disability rights movement in the 1970s. Laura recognized these disconnects and used her writing to challenge preconceived notions, educate people on disability, and garner support to achieve real change in her community and beyond.