Story

The First Draft: Colorado History Over a Few Beers

(14 minute read)

Coloradans love our local beer. The first locally brewed keg was tapped in Denver to rave reviews from residents at the end of 1859. Today more than 360 breweries throughout the state—encompassing both the world’s largest beermaking plant and the smallest nano-operations—pour locally made libations for appreciative patrons. In every corner of this rectangular patch of mountains and plains, liquid artisans are crafting an array of exceptional beverages that pair well with the joys of living here. An intrepid (and thirsty!) aficionado could watch the Colorado sunset with a different locally made beer in hand every evening for nearly a decade without repeating.

Shine a light on one of those pints at just the right angle and it will reveal broader themes in Colorado’s story, such as the social networks of newly arriving immigrants, women’s evolving political clout, the suburban lifestyles of returning GIs and their families, the Chicano civil rights movement, Coors’s role in defining the Rocky Mountain mystique, and the brewpub politics that launched a governor and presidential candidate. Each story opens to us each time we open a beer. From the earliest mining camps to today’s booming cities, the history of beer in the Centennial State illuminates the historical moments that have shaped—and continue to shape—our experience as Coloradans.

As Americans and others of European ancestry chased dreams of wealth in mineral rushes throughout the US West in the latter half of the nineteenth century, saloonkeepers followed close on the miners’ heels. Saloons were often the first establishments in camp—even when calling them an “establishment” might mean stretching the truth as taut as the canvas on their tent frames. Most of these saloons served some form of whiskey, which was more efficient and cost-effective to transport than kegs of beer. Bulky, heavy, and liable to spoil en route, beer required brewers to work close to sizeable populations of thirsty consumers. Whiskey had none of these disadvantages and was, accordingly, the libation of choice.

Note that some of the patrons at this saloon are pictured holding carpentry tools, a testament to the demand for construction workers and other trades to support the miners as towns sprung into being at gold and silver strikes throughout the West. Perhaps in this case, their project was building more comfortable saloon quarters before winter arrived!

Beer as we know it today arrived in the Rocky Mountains with the Colorado Gold Rush. In the rambunctious twin cities of Denver and Auraria, nearly any form of enjoyment could be had for the right price. But beer proved hard to find. Frederick Salomon, a merchant, recognized a market for the liquid gold, and in December 1859 he and a partner opened the Rocky Mountain Brewery in Auraria at Tenth and St. Louis (Larimer) Streets, on the site of today’s Auraria Campus. The thirsty miners gave the brewery’s first beers good reviews. Those miners’ taste notwithstanding, Oscar J. Goldrick, an early Denver schoolteacher, recalled in the Rocky Mountain News on July 12, 1872, that the original Colorado beer, “though quite drinkable, was as innocent of hops as our early whiskey was of wheat or rye.”This is the only known image of the Rocky Mountain Brewery, the first commercial brewing enterprise in the territory that would become Colorado. It pictures the brewery in its second location in the young town of Highland, across the Platte River from Denver, which opened with a lagering cellar in 1861.

Most of the beer consumed during the first decades of Colorado’s American settlement was lager beer produced by local brewers. It was enjoyed in saloons by men (and, apparently, the occasional pet donkey, probably rescued from the mines), since it was difficult to bottle for home consumption and social mores prevented respectable women from drinking in public.

Saloons like Cripple Creek’s White House often served as social centers for ethnic enclaves, where men far from home and family could find the comfort of familiar customs, converse in their native language, receive mail, share news from home, get leads on work, and enjoy the camaraderie and diversion that proved hard for them to come by elsewhere in American society. Some saloonkeepers cashed paychecks, offered loans, and stored valuables in the safe for patrons with limited access to or understanding of the banking system. Others shepherded the formation of fraternal organizations to ensure that countrymen and their families were insured against the hazards of their dangerous occupations and received proper burials when tragedy struck. Likewise, saloons provided laborers with space for union meetings. More than one sociologist at the time ascribed the saloon’s popularity to its role as “the workingman’s club.”

In 1892 Colorado counted twenty-three breweries in operation. These brewers were always looking to expand their markets, but the problems of bulk and spoilage associated with shipping beer over long distances had constrained their ambitions. However, a suite of technological advances began to free brewers from their local shackles and transform the brewing business into a national industry.

As railroad networks expanded across Colorado during the latter decades of the nineteenth century, the recently discovered pasteurization process and the invention of the crown cap to seal bottles made it possible to efficiently package and ship large quantities of beer without spoiling. Note the train cars in the foreground of this image of the Zang Brewery in Denver, lined up to carry Zang’s beer to customers in Colorado and beyond. These advances allowed the larger brewers on the Front Range—particularly Zang’s, the descendant of the original Rocky Mountain Brewery, as well as Coors in Golden—to ship to more distant markets around the state. By the same token, out-of-state breweries began shipping their product into Colorado. The first advertisements for Budweiser appeared in Colorado newspapers in the late 1870s.

Coloradans voted to prohibit the sale of all alcoholic beverages within the state beginning in 1916. Four years later, the nation followed suit with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920. Progressive reformers advocated temperance in response to fears that Americans’ drinking habits had become a public health crisis. As alcohol consumption in the United States reached historically high levels, reformers saw alcoholism trapping families in poverty, destroying drinkers’ health, and engendering violence, particularly in the home. Women and children suffered most at the hands of drunken men, and accordingly enfranchised women—first in Colorado and then nationally—played a leading role in the Prohibition campaign.

Drinking rates did decline during Prohibition, but lawlessness notably increased as many Americans scoffed at the dry law and organized crime grew to supply their continued demand. Furthermore, some xenophobic elements within the Prohibition movement targeted the immigrant communities that centered on saloons, and the resurgent Ku Klux Klan often served as vigilante enforcers of the dry law.

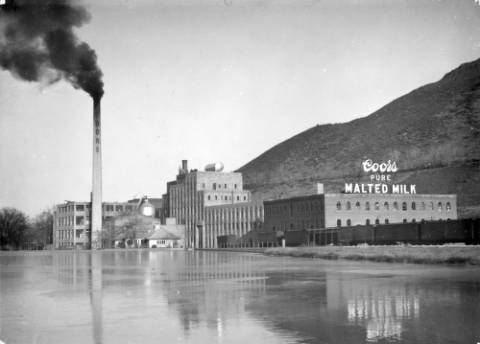

When the US economy careened into the Great Depression, men stood in breadlines as breweries sat idle. Coors kept its malthouse operating by retooling much of the brewery to produce malted milk, among other ventures, but nothing could fully replace the brewing industry’s economic impact. By 1933 a majority of Americans—once again led by women under the auspices of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform—judged the “noble experiment” a failure and welcomed repeal with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment.

As people in Colorado and around the country moved out to the suburbs during the decades of prosperity that followed World War II, brewers followed them home. No longer wishing to be associated with saloons, which never recovered their prominent societal role after Prohibition, brewers portrayed their beer as an essential part of a happy American home.

Beginning in 1945 a brewers’ trade group launched an advertising campaign aimed at depicting the ways in which “Beer Belongs” at home. Wary of the return of Prohibition, the brewers presented their product as a quintessential part of everyday life that men and women enjoyed together. Advertisements featured middle-class couples or groups of family and friends enjoying beer in a variety of familiar settings like backyard barbecues, family gatherings, gameday parties, and vacation spots. Every ad insisted that “Beer Belongs,” often explaining, “In this friendly, freedom-loving land of ours—beer belongs . . . enjoy it!” Each one also emphasized that beer is “America’s Beverage of Moderation.” The campaign successfully reflected new attitudes toward beer’s role in American life. By the start of the 1950s two-thirds of American households kept a few cold ones in the fridge.

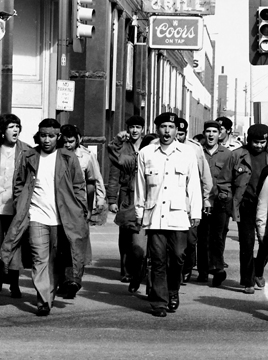

Brewers may have wanted to belong in American homes during the postwar decades, but not all Americans felt welcome in the brewing industry. In the late 1960s activists in Colorado’s Chicano Civil Rights Movement, known as El Movimiento, began calling for a boycott of Coors to protest unfair hiring practices. This photograph shows Chicano/a protesters marching in Denver in 1973. Labor unions, gay and lesbian groups, the NAACP, and other civil rights organizations joined the boycott, all citing unfair or discriminatory treatment by the company.

Coors beer became a flashpoint in the era’s contentious political climate, as some members of the Coors family—deeply wary of government regulation in the wake of Prohibition and frustrated by employees’ labor demands—supported the rise of the conservative New Right embodied by Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan. As Coors grew into one of the nation’s largest breweries by the early 1970s, even though it was still only sold west of the Mississippi River, the boycott brought together a variety of previously separate social movements to challenge practices associated with the family’s conservative political views. Ultimately, the long-running boycott did not produce any clear victories for the activists, but it did tarnish the company’s mystique and hurt sales. By the late 1980s a new generation of leadership at Coors began to focus on making amends with communities it had offended. Today the company that operates the world’s largest beermaking facility is noted for its corporate citizenship, particularly in its support of minority and gay and lesbian consumers.

Charlie Papazian moved to Boulder in the early 1970s to work as a teacher and enjoy hiking and camping in the Rocky Mountains. He joined a wave of new Coloradans during the decades after World War II, as the state’s population grew at a rate not seen since the decades of gold and silver rushes a century earlier. They came for the booming economy along the Front Range as well as the lifestyle and recreational opportunities afforded by living amid such spectacular landscapes. These New Westerners were increasingly likely to see the region’s precious natural resources, which had historically driven the western economy, as treasured environmental amenities ideal for recreation rather than extraction.

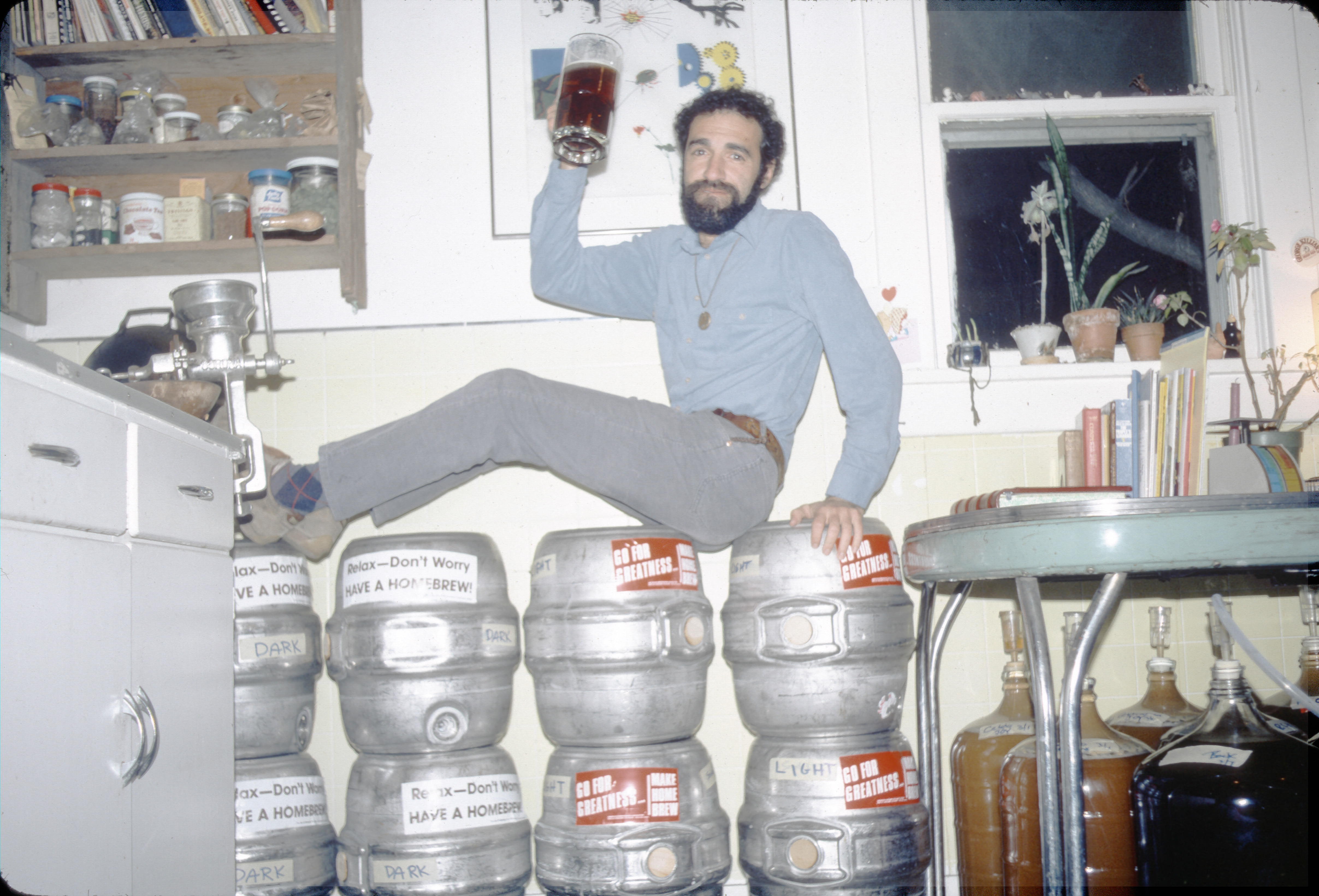

In Boulder, Papazian taught elementary school by day and began teaching homebrewing classes in his kitchen in the evenings, encouraging a growing community of friends and beer enthusiasts to subscribe to his mantra: “Relax—Don’t Worry. Have a Homebrew!” This photo shows him heeding his own advice in his kitchen in 1983. By that point, he had founded the American Homebrewers Association (with Charlie Matzen), organized a handful of “Beer and Steer” campouts in the foothills above Boulder, started the Great American Beer Festival, and had taught, by his own estimation, nearly a thousand Coloradans to brew. Among them he includes at least two notable alums: one of the founders of Boulder Brewing, which opened in 1979 as the first new brewery in Colorado since Prohibition’s repeal, and one of the cofounders of New Belgium Brewing, now one of the largest breweries—craft or otherwise—in the nation.

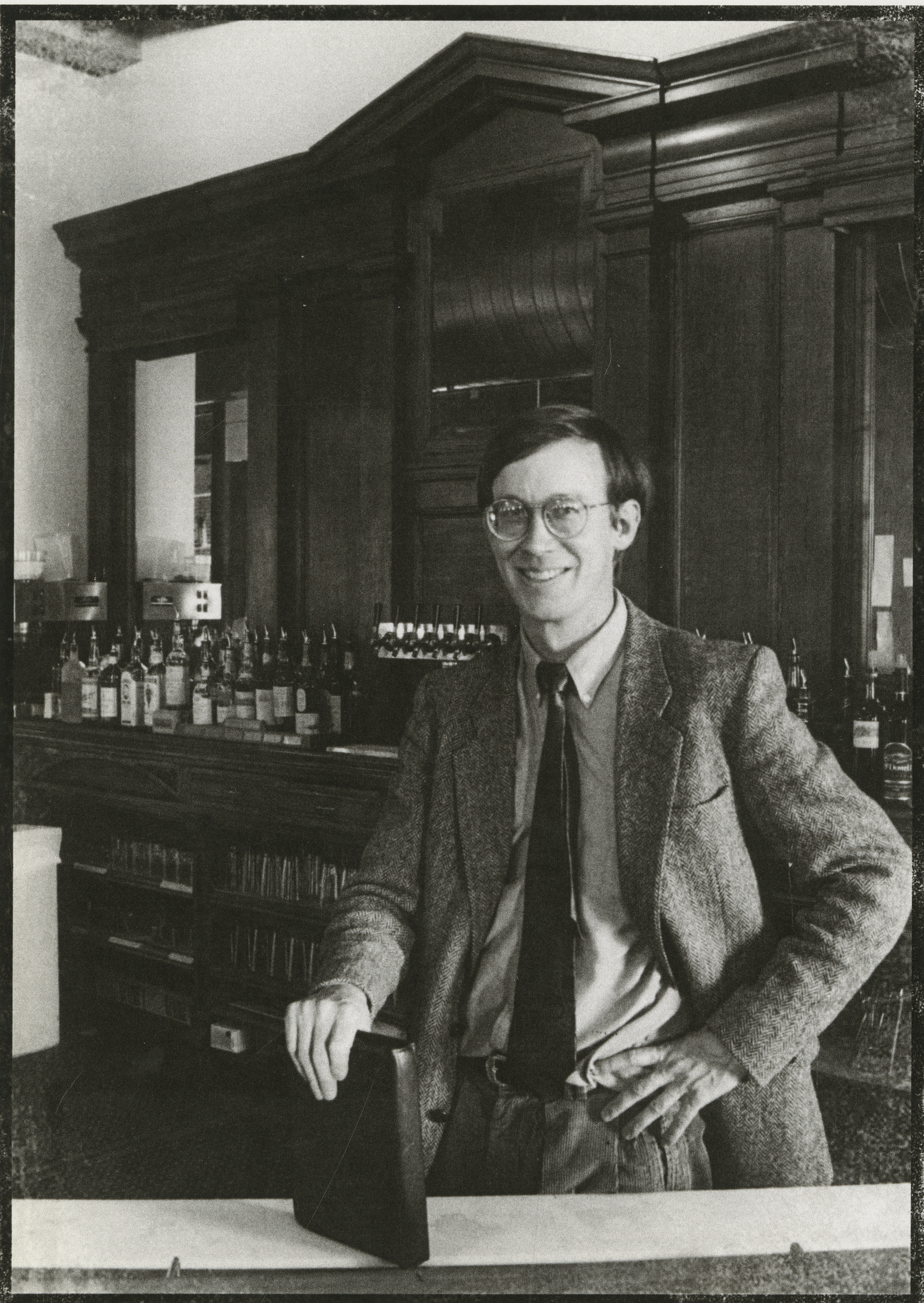

John Hickenlooper at the Wynkoop Brewing Company, 1988

In 1988 the Wynkoop Brewing Company opened as the first brewpub in Colorado. On its opening night, thirsty crowds thronged to what had been a neglected warehouse in a dilapidated part of Denver, making it clear that what people then called “microbrews” had an enthusiastic customer base in Colorado. Bartenders passed out twenty-five-cent pints as quickly as they could pour them that night—more than six thousand by last call—and the growth of Colorado’s craft beer industry has rarely slowed since.The popular brewery helped spark the redevelopment of Denver’s then-struggling Lower Downtown district, now a vibrant neighborhood where residents and visitors can still enjoy a Wynkoop beer or choose from a long list of newer restaurants and breweries. In the ensuing decades, the growth of the craft beer industry in Colorado mirrored the rise of one of the Wynkoop’s founders. John Hickenlooper, pictured here around the time of that memorable opening night, has progressed from brewpub owner to Denver’s mayor to Colorado’s governor to, as of this writing, candidate for president.

Coors invented aluminum beverage cans in 1959, but as craft brewers began to establish a presence in the market in the 1980s and ’90s, they generally packaged their product in bottles. Most couldn’t brew enough at a time to fill a typical canning run, and they were happy to encourage the cachet that associated fine beverages with traditional glass bottles. That philosophy changed in 2002, when the Oskar Blues Brewery in Lyons put Dale’s Pale Ale in aluminum cans. Three years later, The New York Times anointed Dale’s the best pale ale, suggesting that the can might have protected the beer’s flavor better than a bottle could.

Oskar Blues happily pointed out that cans were also easier to pack along for bike rides, ski days, camping trips, and other outdoor recreational pursuits that had drawn so many people to Colorado—including Dale Katechis, the brewery founder and an avid mountain biker. Colorado consumers quickly discovered that the canned craft beer paired nicely with their love of the outdoors, and the infinitely recyclable aluminum cans were easier on their environmental consciousness. Craft brewers had already positioned their beers as one of the amenities associated with the West’s high quality of living, and canning their beers allowed them to draw an even stronger link between outdoor recreation and their beer. The industry took note, Coloradans took the beer along on their outdoor adventures, and today Colorado’s best beers come—and go—in cans.

In 1982 Charlie Papazian launched the Great American Beer Festival when he invited a small group of professional brewers to Boulder to trade tips and tastes at a homebrewer’s conference. That first festival featured twenty-four brewers serving forty-seven different beers to eight hundred festivalgoers. From that modest beginning, the festival has grown along with the craft beer industry into one of the world’s bucket-list brewing events.

Today the festival has moved to downtown Denver, where more than sixty thousand beer enthusiasts and eight hundred brewers from around the country turn the city into the center of the beer universe for a long weekend each fall. The festival’s judges have defined and refined styles of beer as they annually award the best brewers in the United States. Revelers celebrate the quality and creativity of the nation’s vibrant craft brewing industry. And breweries like Fort Collins’ New Belgium Brewing, a longtime festival stalwart, showcase their lineup of beers, and often a few special pours, for festive fans.

For Further Reading:

Newspaper sources for this essay included the Rocky Mountain News, Golden Telegraph, and The Denver Post. Books included Thomas J. Noel, The City and the Saloon: Denver 1858–1916 (University Press of Colorado, 1996); Elliott West, The Saloon on the Rocky Mountain Mining Frontier (University of Nebraska Press, 1979); Stanley Baron, Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States (Little, Brown, 1962); William Kostka, The Pre-Prohibition History of Adolph Coors Company, 1873–1933 (Adolph Coors Company, 1973); and Maureen Ogle, Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer (Harcourt, 2006). Also see Royal Melendy, “The Saloon in Chicago” (The American Journal of Sociology, November 1900); Jon M. Kingsdale, “The ‘Poor Man’s Club’: Social Functions of the Urban Working-Class Saloon” (American Quarterly, October 1973); Nathan Michael Corzine, “Right at Home: Freedom and Domesticity in the Language and Imagery of Beer Advertising, 1933–1960” (Journal of Social History, Summer 2010); and three articles from Journal of the West (Spring 2016): B. Erin Cole, “A Brewing Controversy: The Coors Boycott, 1967–1987”; Jason L. Hanson, Michael McCullough, and Joshua Berning, “New West, Brew West: Home Brewing an Industry in the West”; and Sam Bock, “Crafting the Can: What the Aluminum Beer Can Teaches Us about the Twenty-First-Century West.” Allyson Powers Brantley’s Ph.D. dissertation, “We’re Givin’ Up Our Beer for Sweeter Wine”: Boycotting Coors Beer, Coalition-Building, and the Politics of Non-Consumption, 1957–1987 (Yale University, 2016), is an informative source on the Coors boycott and the company’s response.