Story

Dr. Richard Corwin and Colorado’s Changing Racial Divide

Editor's note: As many communities around Colorado reexamine how our public buildings and places are named, we take a look at one man who left his mark on Pueblo. Richard Corwin was an advocate for eugenics and an outsized personality with one of the state’s largest employers. This story is excerpted from Making an American Workforce: The Rockefellers and the Legacy of Ludlow, edited by Fawn-Amber Montoya (University Press of Colorado, 2014).

The Pueblo Hall of Fame is housed in College Hall on the campus of Pueblo Community College. One of its inductees is Dr. Richard Warren Corwin, the former chief surgeon of Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, the largest private employer in the state at the time he died in 1930. The plaque under Corwin’s picture calls him “an ideal physician, an exemplary community advocate, and a marvelous combination of genius, energy, generosity and executive ability.” A local middle school and the St. Mary–Corwin Regional Medical Center are named for him. “Many of his innovative concepts made a big impact on the care of Pueblo citizens,” explains the plaque.

The preeminent historian of CF&I, H. Lee Scamehorn, has written that “Corwin’s emphasis on community and social betterment reflected Progressive Era middle-class concerns for Americanizing recent immigrants, who constituted the majority of the workforce” at the company. Besides his concern about Americanizing some recent immigrants, Corwin’s belief in eugenics strongly demonstrated that he cared little for Americanizing others, especially the ones who were not white.

Corwin (second from left) joins CF&I superintendent John Osgood (third from right) and Governor James Peabody (center) in an undated image. With Osgood's support, Corwin expanded CF&I’s Medical Department to thirty-eight surgeons who cared for 60,000 miners and family members in Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Francis Galton, a half-cousin of Charles Darwin, coined the term eugenics in 1883. It refers to a pseudoscientific philosophy that promotes an intelligent and healthy human race through the manipulation of heredity. Specific manipulations of heredity by eugenicists included forced sterilization, forced institutionalization, forced abortion, and euthanasia. Eugenics flourished in the early 1900s as a response to the influx of eastern and southern Europeans into America, since these immigrants were seen as a threat to the quality of the American gene pool. Perhaps the most prominent practitioner of this ideology in Colorado during its heyday was Dr. Richard Warren Corwin.

Race was a fluid concept during Corwin’s lifetime. It not only referred to the color of a person’s skin, but sometimes ethnicity or even a group of people’s collective intelligence. Corwin’s available eugenics-related statements suggest a broader effort at achieving white solidarity against a growing Mexican and Mexican American population that eugenic supporters saw as a threat. That perceived threat arose not from simple racism, but from couching those racist beliefs in the cover of a pseudoscience that strengthened greatly over the last two decades of Corwin’s life. The purpose in describing Corwin’s beliefs is not to deride the legacy of a man who did so many positive things for Puebloans of all races, but to illustrate the changing racial divide in southern Colorado from the early 1910s through the late 1920s.

Richard Corwin was born in New York in 1852. While growing up, he had a deep interest in observing wildlife and enjoyed taxidermy as a hobby. His skill in taxidermy led him to Cornell University, where he received his formal education and was appointed taxidermist. In the years between 1874 and 1878, he held the position of curator at the museum at Michigan University, where he taught anatomy, composition, and microscopy. At the same time, Corwin studied at the University of Michigan’s Medical Department, graduating in 1878. He interned for a year at Saint Luke’s Hospital in Chicago and also studied overseas at European hospitals, becoming educated in hospital management and construction.

The Colorado Coal and Iron Company (later known as the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company) hired Corwin to organize its medical department in Pueblo. He arrived in 1881 to find a workforce of about two thousand men in the steelworks and a severely inadequate medical facility. The following year, an increase of steel workers brought with them a typhoid epidemic. The epidemic prompted the Colorado Coal and Iron Company and the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad Company to build a hospital that could accommodate thirty patients at a time.

Corwin worked for CF&I from 1881 to 1928. While there, he embraced his position as chief surgeon of the Medical Department and superintendent of the Sociological Department. When he arrived, the Medical Department had only two physicians who cared for over two hundred workers and their families. With support from CF&I superintendent John Osgood, Corwin led CF&I in a medical revolution, and by February 1902 the Medical Department had increased to “38 surgeons who cared for 60,000 persons—employees and their families—at the thirty-eight mines and mills in Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico,” according to company magazine Camp & Plant.

With the influx of CF&I jobs and European immigrants, Corwin supervised the expansion of the Minnequa Hospital on the shores of Minnequa Lake in Pueblo. Minnequa Hospital replaced the old 1901 hospital on the east end of Abriendo Avenue. Many observers lauded his hospital for its superb examination tables, X-ray machines, steam sterilizers, and building architecture that allowed for maximum sunlight to enter, the movement of fresh air within the building, and handicap access points.

A woman and children pose with their pets at a house in a coal camp in Las Animas County, around 1900.

Colorado Coal and Iron created the Sociological Department in 1901 specifically to resolve racial and ethnic differences that had led to a strike at CF&I that same year. In its earlier years, the department stressed Americanization designed to bring people together, not racial differences designed to tear them apart. According to Scamehorn, Corwin ran the department with concerns that went well beyond those of an ordinary company surgeon. “In numerous ways,” Scamehorn writes, “the sociological department improved the quality of life in communities. It concentrated its efforts on education, domestic and industrial training, and leisure activities."

As Corwin’s Medical and Sociological Departments flourished in the early 1900s, CF&I struggled with debt until John D. Rockefeller Jr., son of the famous oil baron, bought the company. In response to an economic downturn in 1908, management cut the Sociological Department budget drastically, posing a serious threat to Corwin and his work trying to boost employee morale, motivation, and safety. But with Rockefeller attempting to pull CF&I out of debt, the demand for productive and able-bodied workers created pressure on Corwin to reduce worker injuries and maintain a healthy workforce. Rockefeller influenced industrial relations at CF&I in different ways too. He spent at least $100 million dollars on eugenics-related programs nationwide long before the popularity of this racist ideology peaked. Some of that money went to improve the eugenics-related programs at CF&I’s Sociological Department.

Corwin left a published record that documents his belief in eugenics. In his 1913 Report of the Joint Committee on Health Problems in Education, he shows great anger in response to a study that analyzed the sanitation of rural school districts throughout the United States. He makes his position on eugenics crystal clear: “The average rural schoolhouse in relation to its purpose is not as well kept or as healthful as a good stable, dairy barn, pigpen, or chicken-house. But what more could be expected from a government that creates a cabinet department for animals but fails to recognize one for man; that appropriates millions for brute heredity and little or nothing for human eugenics?” As he continues, he describes the threat to the white race in more explicit terms:

In our schools we find 2 percent of children known to be feeble-minded; in some schools, they average as high as 30 percent—and this does not include the morons, the higher class of defectives: . . . it is well known that the feeble-minded constitute the major portion of criminals, prostitutes, epileptics, drunkards, neurotics, paupers . . . found in and out of prisons; and that in a large number of our states the mentally defective are cared for when young but when reaching maturity and most dangerous are turned loose upon the community to become parents of a class, with each generation becoming more depraved. If for the next hundred years our schools would discontinue all higher and aesthetic education and devote their energy to improving the human stock; to feeding and breeding; to teaching that acquired traits die with the body, that inherited traits pass to the next generation, and that the laws of heredity are constant and are the same for bug and man . . . and to educating the people to know that environment is important but heredity more important, and eugenics most important, and that thru eugenics is the only hope of improving our race or saving our nation—if this were done, at the end of the century we should find the people not only 100 years older but 100 percent better, stronger, and wiser.

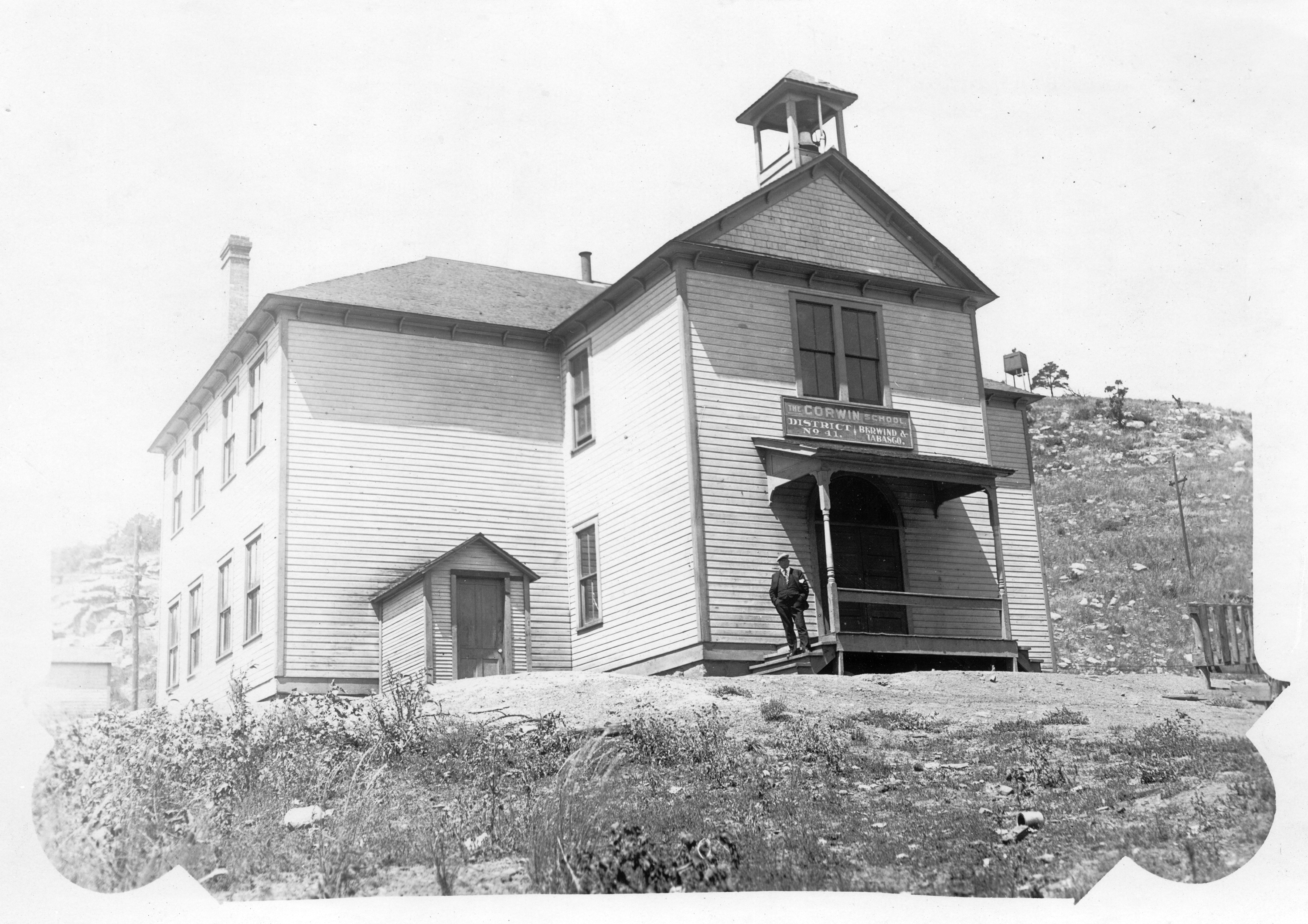

Colorado Fuel & Iron named its school in the coal camp of Tabasco the Corwin School (shown here around 1910) in honor of eugenicist and chief surgeon Dr. Richard Corwin.

The children of immigrants overwhelmingly dominated the schools Corwin dealt with at CF&I coal camps and in Pueblo. This response blames the poor sanitation conditions in these schools on the racial characteristics of the students. Mentioning eugenics is a logical response for someone who believes that the environment these children lived in is a direct result of their genes.

In other pronouncements, Corwin couched concern for the race in terms related to citizenship. This was a common tactic for eugenicists trying to alarm native-born whites about the threat of race mixing. In The Administration of Health Departments—The Colorado Plan, from 1913, Corwin notes that the child of today is the citizen of tomorrow and that it is the schools’ responsibility to report on the physical, mental, and moral defectiveness of any and all children attending school:

Many now know and understand but are lacking in the very mental qualifications that make for good and best; not until there is progress in moral mentality can there be racial improvement . . . we spend $32,000,000 annually upon the insane and encourage them to multiply their kind by giving them their liberty; we expend immense sums upon the feeble-minded, keep them under control when harmless, and turn them loose to reproduce more fools when of the age to become parents; in like manner we deal with the criminal, the epileptic, the alcoholic, and the prostitute, who are mental and moral defectives, permitting them to propagate their type . . . . We teach environment and neglect heredity. We are a success at feeding but a failure at breeding.

For him, the solution to this problem was to teach eugenics in schools (presumably to white students since children who were threats to society would have been identified and isolated):

The value of environment cannot be overestimated—it should be taught in every grade and by expert teachers, especially prepared; but of more importance is the teaching of the science of heredity. Heredity begins at the beginning; it is the foundation of existence; environment, the superstructure of life. We should teach better heredity—eugenics; every school and every grade should have instruction in heredity and eugenics. The cause of feeble-mindedness, criminality, epilepsy, alcoholism, pauperism, and prostitution should be known and the prevention understood. The cure cannot be brought about thru environment; upon eugenics rests the salvation of the race.

Perhaps unrestrained from the need to keep even the most racially inferior workers happy and productive, Corwin let his true feelings show.

In 1917 and 1918, CF&I experienced a reduction in laborers, nurses, and doctors as the United States entered World War I. That loss could not have come at a worse time. In 1918, a worldwide influenza epidemic swept through CF&I towns and camps, overwhelming an understaffed medical department. Corwin’s “Annual Report of Chief Surgeon” to CF&I President J. F. Welborn pushed for more efficiency within the Medical Department during this tumultuous time. The epidemic heightened Corwin’s eugenics-influenced beliefs that sanitation and hygiene standards within the CF&I towns were not being upheld due to the unfit and feebleminded.

In response to the lack of sanitation and hygiene that Corwin perceived at the hospital, he issued a three-tiered classification system that separated those who were willing and able from those who were feebleminded and unfit:

- Those who know, have self-control, feel a moral responsibility, and exert every effort to protect themselves and others.

- Those who know, but do not care, are indifferent, morally weak, shun responsibility, and protect neither self nor neighbor.

- Those mentally feeble, unable to comprehend or reason, have no power of resistance, and are a constant source of annoyance and danger.

Corwin noted that the first class should be given every protection possible, the second class should be educated and reformed if possible, and the third class “should be guarded and protected. The state should care for the feeble-minded . . . those needing asylum . . . for life. The law cannot be too stringent for the benefit and protection of those who “can” for the benefit of the race.” Corwin’s hospital saved thousands of Puebloans—including many who did not work for CF&I—during the epidemic, but they might have done even more if not for this kind of policy.

In 1922, Corwin announced the need for mental examinations to screen for the unfit among the applicants for employment at CF&I, referencing the army’s use of mental tests, along with schools and juvenile courts that used them as well. The mental exams at CF&I bore a striking resemblance to the literacy tests aimed at disenfranchising southern Black voters during and after Reconstruction, since both aimed at disempowering a class considered inferior to the white elite.

In 1927, just as eugenics had passed its peak in popularity and shortly before Corwin’s death, he accepted a nomination to be part of the Colorado Eugenics Committee. The committee’s purpose was to create pro-eugenics propaganda and push eugenics legislation through the state of Colorado. In the September 1928 edition of the Industrial Bulletin, Corwin spoke of eugenics by referencing Chicago-based Dr. William J. Hickson’s assessment that “the criminal is a ‘primitive’—he is a primitive man, underdeveloped in a part of his brain structure. This whole problem is a hereditary problem.”

Corwin died in 1930. He did not live long enough to see the racial ground in southern Colorado and the country’s attitude toward eugenics shift.

As late as the 1890s, the majority of Colorado coal miners were native-born Americans or immigrants of English, Scottish, Welsh, or Irish descent. A severe labor shortage, as well as the threat of strikes, led mine owners to recruit immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and especially Mexico. They hoped that racial and ethnic divisions within the workforce would make it impossible for workers of all kinds to unite. On August 1, 1918, approximately 20 percent of CF&I’s miners were Mexican or Mexican American. After strikes in 1919 and 1921, as many as 60 percent of the company’s new hires in both the mines and the mill were people of Spanish/Mexican ancestry. Nationwide immigration restrictions on Europeans instituted by Congress in 1921 and 1924 assured that CF&I would have to employ a sizable number of these non-European immigrants for many years to come.

In the late nineteenth century, eugenicists—indeed, probably most native-born Americans—assumed that the Polish, Italian, and Slavic workers who appeared on America’s shores every day belonged to inferior races despite their white skin. As Corwin’s workforce became increasingly Mexican, delineating the worthy from the unworthy poor became much easier as they could be separated by skin color.

After Corwin’s death in 1930, the economic situation at CF&I turned so dire that management let go many, perhaps close to all, of their Mexican and Mexican American employees. Whatever hard feelings these workers had about the company’s racial attitudes no longer mattered to their former employer.

The racial makeup of southern Colorado, like our society in general, is changing today just as it was in Corwin’s time. The social and economic costs and benefits of immigration are just as hotly contested now as they were then. Corwin’s persistent belief in eugenics should remind us that racism persists even as racial classification systems change. More important, it demonstrates how racist philosophy can be continually adapted to fit changing demographic circumstances.

Corwin’s name remains throughout the Pueblo cityscape because of what he built and as a memory to his medical legacy. His racial legacy, while much more controversial, is still worthy of consideration because of what it can still tell us about race relations in Colorado today. The dynamics underlying immigration and employment in Corwin’s day fostered extremist ideologies and disturbing solutions, just like they do now.

For Further Reading

For more about CF&I, see H. Lee Scamehorn, Mill & Mine: The CF&I in the Twentieth Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992). For more about the eugenics movement, see Ruth Clifford Engs, The Eugenics Movement: An Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005); Edwin Black, The War against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003); and Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Find CF&I correspondence and publications, including digitized copies of Camp & Plant, at the Bessemer Historical Society and CF&I Archives in Pueblo.

environment is important but heredity more important, and eugenics most important, and that thru eugenics is the only hope of improving our race or saving our nation