Story

The Master Weaver of the San Luis Valley

Eppie Archuleta’s Legacy

Far beyond Eppie Archuleta’s technical abilities, awards, and accolades as a master weaver, she was a weaver of artistry and legacy—her work strengthened by the warp of her ancestors and enriched by the weft of faith, love, and kindness.

Eppie Archuleta could often be found weaving in the quiet, still hours of the night from dusk until dawn. With her children asleep and the Valley silent, Eppie would transform wool—dyed by the plants of the earth—into designs that echoed the patterns of her Native American and Spanish ancestors. Her work told the stories of people through portraits and illuminated the beauty of landscapes and animals. Her love for the loom bloomed later in life, but her weaving skills were cultivated at a young age. Eppie inherited the art of weaving from the generations of artisans before her.

The traditional Hispanic folk art of weaving in the San Luis Valley has its roots in sixteenth-century northern New Mexico. Sheep were introduced to the region by Spanish settlers and weavers used the wool to make beautiful, unique textiles. This centuries-old art form is a continuing tradition, often passed down through familial generations: families like the Martínez family of Medanales, New Mexico. The legacy of Eppie Archuleta is part of this weaving heritage that spans over five generations.

Eppie’s New Mexican Roots

Epifania “Eppie” Archuleta was born on the Catholic feast day of Epiphany, January 6, 1922, in Santa Cruz, New Mexico. Growing up in Medanales, New Mexico, Eppie’s childhood consisted of helping with the family farm, listening to her father’s stories after a hard day’s work, and learning how to weave.

Eppie’s father, Eusebio Martínez, was a school teacher, postmaster, and skilled weaver from Chimayó, New Mexico. He could trace his ancestor’s weaving tradition back to the seventeenth century. Eppie’s mother, Agueda Salazar Martínez, or Doña Agueda, as she was known, was a skilled and renowned weaver, recognized as a matriarch of Hispano weaving in New Mexico. Over the years, she received numerous honors and awards.

Weaving was an integral way to add to their large family’s income. All ten of the Martínez children, including Eppie, would help in the weaving-related duties such as processing wool, gathering plants to dye the yarn, and weaving on the loom. While Eppie did not enjoy weaving initially, she developed a love and appreciation for the art form later in life. She said, “They made me do it. I didn't do it because I want to. But looks like it printed on my head pretty good. I love it now…I just love to weave.”

The Art of Weaving

In the 1950s, Eppie and her husband, Francisco “Frank” Archuleta moved to Capulin, Colorado to raise their ten children, eight of whom lived to adulthood.

Eppie used weaving to supplement her family’s subsistence farming income, which allowed her to stay home with her children. Using the traditional techniques that she observed and learned during her childhood, Eppie processed her own wool by washing, carding, and spinning it. Then, she used the resources of the earth to dye the yarn.

Eppie’s daughter Norma Medina, a notable weaver herself, remembered, “My dad always had a lot of sheep. We would use our own wool. When he would shear the sheep, she would take the wool that didn’t have too many stickers. We’d wash it and hand-card it.”

To wash the wool, it would be placed in giant tubs of water heated over a wood fire. Then, using plants and herbs, like cota, aspen, juniper, bark, weeds, and black walnut hulls, she would dye the fresh wool into rich, vibrant colors, ready to be woven on the loom.

In a 1980 interview for a journal of women’s studies, Eppie described the process. “And at the same time that the weeds are boiling, I have this other wool over here in the mordant boiling, too, at the side. It have to be the same temperature. I boil the thing already two hours. Now, I have to boil them again another two to get the color in the wool. And it takes about two hours for these weeds to get the color I want.”

Passing Down a Love for the Loom

While weaving was initially just an extra source of income, Eppie began to discover a love for the loom and her own creative style. Years of cultivating her skills allowed her the ability to experiment with weaving as an artistic form of storytelling. She would challenge herself to do pictorials and large Navajo blankets—which were very valuable and intricate. According to her daughter, Norma, she was unafraid of challenges and would say, “I can do that.” Eppie embraced both traditional and contemporary design styles in her weavings. Over the years, Eppie was recognized for her work with several awards and honors.

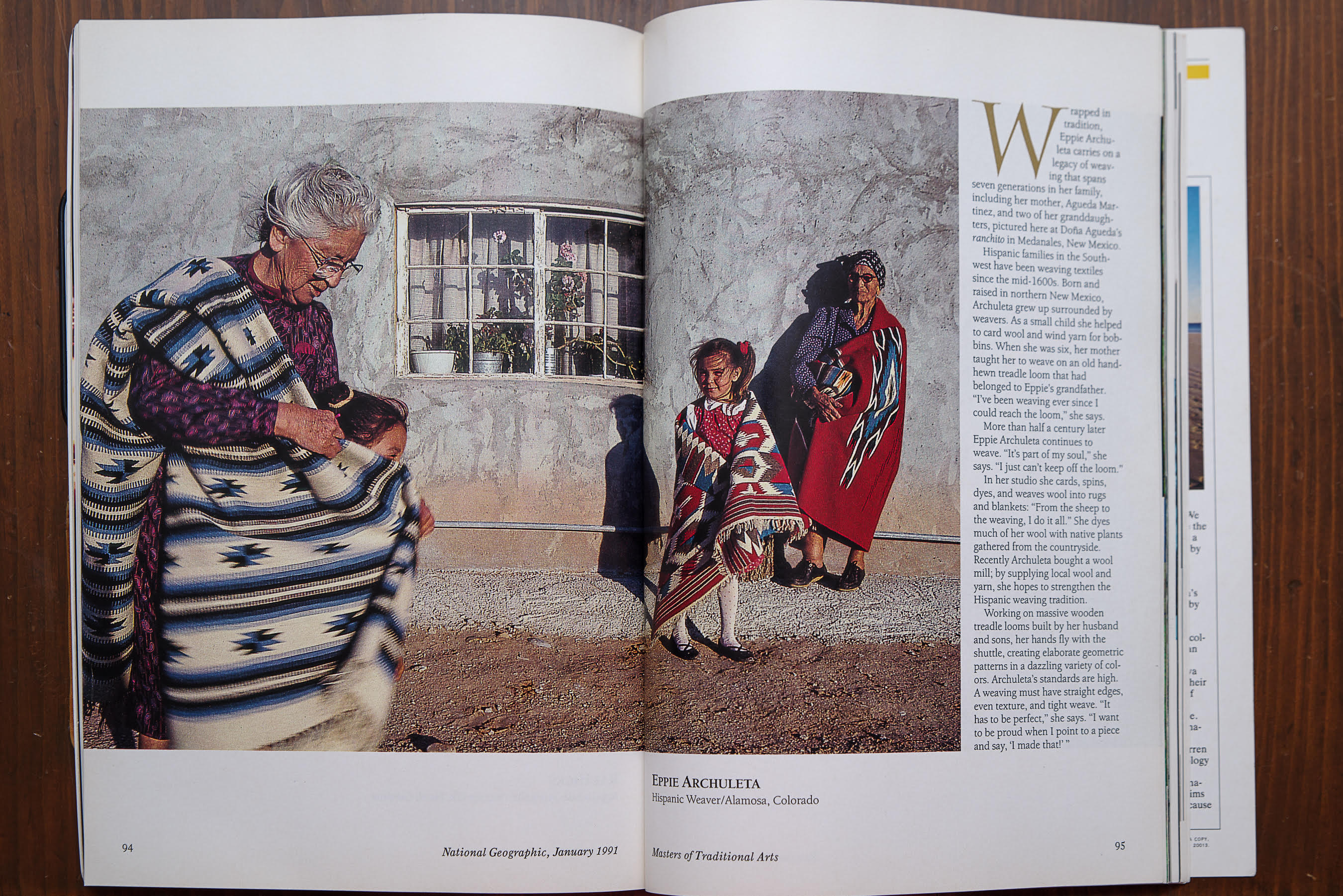

Eppie Archuleta was featured in a January, 1991 article in National Geographic magazine. The magazine photographer, David Alan Harvey, photographed Eppie for a series titled “Masters of Traditional Arts.”

In 1983, Eppie received the Colorado Governor’s Award, and she was awarded the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1985. In folk and traditional arts, this award is the highest honor. In 1991, she was profiled in a National Geographic magazine article. In the article, she described weaving as an integral part of her life. “It’s part of my soul,” she proclaimed.

Over the years, her artistry received many more accolades and is on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institute. In 1995, Eppie received an Honorary Doctorate in Arts from Adams State University, an accomplishment that her daughter, Norma, is most proud of. Norma explained that the doctorate demonstrated that her community valued and recognized Eppie as a master weaver and expert artisan for work she did in her latter years.

In 1986, Eppie Archuleta, her mother Doña Agueda, daughter Norma Medina, and granddaughter Delores Medina, were invited to the Festival of American Folklife at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. The four generations of weavers demonstrated their tradition to thousands of people, showing every step of the process from carding to dyeing to weaving.

Eppie’s children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren carry on this century-old tradition. Like Eppie with her own mother, Norma Medina learned the craft by observing, stating, “My mom really didn’t even teach me. I just picked it up…I learned it by watching her.”

Norma Medina has continued the weaving heritage. In the early 1990s, Norma was commissioned to weave the Passion of Christ for St. Peter Catholic Church in Greeley, Colorado. The three-year project was a fourteen-piece Stations of the Cross weaving set. Norma credits the success of her project to the knowledge and creativity she inherited from her mother, grandmother, and ancestors. Like her mother, Norma finds creative inspiration from nature and her faith, stating, “You learn to appreciate nature. When I want to weave something—and my mom, too—we’d look at the mountains and the skies…In our color wheel, too. It comes from all kinds of herbs…It’s an artwork and we don’t realize it…God’s the artist.”

Eppie Archuleta's weaving, a table loom made by Levi Medina (donated by Levi and Norma Medina), and a copy of the Congressional Record honoring Eppie for her lifetime contributions are on display in the Adams State University Luther Bean Museum.

Along with teaching her family how to weave, Eppie passed down the craft to her many students over the years. She taught people in the San Luis Valley community how to weave so that they could supplement their income and enjoy the art. Eppie worked as an instructor for the Virginia Neal Blue Women’s Resource Center and the Los Artes del Valle crafts cooperative. These programs were created to boost the local economy in the late 1950s and preserve Hispano weaving folk art in the area. Eppie would also visit local elementary schools with her miniature loom to demonstrate for the children.

A Legacy of Kindness, Strength, and Grit

Eppie Archuleta’s family, love for weaving, and strong faith were the heartbeat of her life. After her husband, Frank Archuleta passed away, Eppie moved to live with family in New Mexico. She continued to weave as much as she was able to in her final years. Eppie passed away on Friday, April 11, 2014, in New Mexico.

Not only is Eppie’s legacy laced with her many weaving accomplishments, but kindness and compassion were also central to her life. She was quick to help those in need. Chris Medina, her grandson, remembers when Eppie helped a woman who was hitchhiking. Chris said, “She took care of her for a month…My grandma taught her how to weave. She was that kind of a person.”

Later in life, Eppie’s care for others and entrepreneurial spirit inspired her to purchase a wool mill. In the early 1990s, she opened the San Luis Valley Wool Mill in La Jara, Colorado with the help of her family, including her grandson, Chris Medina. Eppie worked to have her mill be a fully operational employer for the people of the San Luis Valley.

Like weaving, Eppie’s endurance and drive were passed down through generations. Throughout his life experiences as an athlete, musician, and other life endeavors, Chris realized that his grandmother’s grit and dedication were traits she had given him. She taught him to “believe and never give up.” Eppie’s legacy continues through her example of determination. Chris Medina talks to his son about his grandmother’s strength and passes down the life lessons he learned from her to keep going through difficult circumstances.

Chris remembers his grandmother’s endurance, stating, “She went from dawn until like ten o’clock at night. She was one of the hardest working people I’ve ever met. My grandma. I admired that…But we never worked on Sundays.” While Eppie was a very hard worker, Norma remembered that her mother would “always make time for her kids.” She recalls her mother carving little toys out of wood or making bows and arrows for the boys of the family.

The Master Storyteller

This multifaceted woman was creative and intelligent. Among her family, Eppie was known as an amazing storyteller. Whether it was stories she had heard from her father growing up or tales she created, her children and grandchildren were the audience for her oral masterpieces. In 2004, one of her stories was published as the book, “Eppie Archuleta and the Tale of Juan de la Burra” by Ruben Archuleta. Eppie’s creativity was expressed through her beautiful weavings, her funny and interesting stories, and in every other area of her life.

Eppie’s years told a story of kindness and strength. This textile artisan was a storyteller at heart and passed down wisdom along with her love for the loom. She inspired her family and her community to appreciate the tradition and art of weaving, be compassionate and kind to others, and never give up when life gets difficult. The art form she inherited was her avenue for helping people and making her community a better place.

The fabric of Eppie Archuleta’s life is woven with the threads of excellence, hard work, kindness, faith, and strength.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Women of the Borderlands The year 1848 marked two notable moments in US women’s history.

Discovering Personal Treasures the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. In this heartfelt account, a refugee reflects on the journey that helped to define what constitutes her most prized possessions.

Understanding Amache: The Archaeobiography of a Victorian-Era Cheyenne Woman Composed around 1870, the photographic portrait of Amache Ochinee Prowers is a window into her complex world.