Story

Collective Loss, Collaborative Recovery

Ernest House, Jr. (Ute Mountain Ute) comes from an extremely long line of environmental stewards. In times of environmental disaster like Colorado’s wildfires of 2020, he sees opportunities to work together. “The threats to our lands are intertwined, but so are the benefits of protecting them,” he notes.

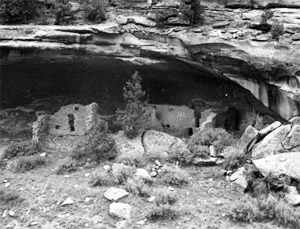

Since 10,000 BCE, my ancestors, the Ute “Nuchu” people, have called Colorado home. Green before green was cool, we survived for generations because of our respect and care for the land. We sustained ourselves for thousands of years by knowing where the game, fish, and medicine were located and respecting their abundance. The first Ute reservation was established in Colorado in 1868, and by the 1900s, our reservation was reduced to a sliver remotely located in Southwestern Colorado. In a matter of forty years, we lost our access to the natural resources that fed our existence. Today, two federally recognized tribes in our state, the Southern Ute and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribes, are managing nearly one million acres of land, with the latter proudly managing a 125,000 acre Tribal Park near Mesa Verde, where we emphasize conservation and stewardship of Ancestral Puebloan culture sites.

Currently, our society is losing our land almost as quickly. Despite our efforts and those of the conservation community, Colorado’s lands, waters, and wildlife are facing serious threats. According to The Center for American Progress, since 2001, we have collectively lost over 500,000 acres of natural lands to development caused, in part, by energy extraction and sprawling housing. Nationally, it’s even worse: the United States loses a football field’s worth of nature every thirty seconds, or about 1.5 million acres a year. Globally, it’s catastrophic: according to the World Wildlife Federation, the average population of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles has dropped 68 percent since 1970. This year, Colorado saw up close and personal what happens when nature is deprived of its ability to function naturally. Wildfires and extreme bouts of weather were regular reminders that something is wrong.

The threats to our lands are intertwined, but so are the benefits of protecting them. Larger conservation efforts like 30x30 plans, which are frameworks to conserve 30 percent of land by 2030, have been presented and supported across the nation with more and more tribal leaders offering support. Even newly tapped Interior Secretary nominee Representative Deb Haaland has proposed and supported 30x30 resolutions. Indian Country cheers her appointment, as we have been waiting for generations for this opportunity to have our voice elevated and represented at this prestigious federal level. Today, only ten percent of our lands are conserved. Protecting 30 percent of our land by 2030 will take the collective efforts of all of us, who must work together to identify lands and waters in our own backyards as well as in the more distant corners of our state.

As we all work together in conservation efforts, we need to ensure tribal engagement and consultation early and often. They should also require engaging communities historically ignored and excluded from the halls of power, including Indigenous voices. As a start, we should consider lands to be co-managed between tribes and the state or federal government, which allows traditional land uses to occur, and acknowledges ancestral homelands in establishing or updating place names.

When it comes to land, water, and wildlife, Indigenous communities know more than anyone how quickly you can be displaced from it all. Even though we’ve been displaced, our histories are written on the land, our songs are embedded in the trees, creeks, and riverbeds all waiting to tell a story. The threats our lands face today require all of us to act. If we’re going to succeed at conserving our natural resources, we must summon our collective will to accelerate the pace and scale of conservation. There is no time to waste.

This article is part of a series through a partnership with the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs to elevate Indigenous perspectives and reflections.

Vision and Visibility

Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice.