Story

"Be True to What You Said on Paper"

the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. Here, a medical sociologist and social scientist argue that to truly arrive at equity in America will require a sincere reckoning with founding mythologies of white superiority.

On April 3, 1968, the night before he was shot to death by an unknown assailant, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his final public address to a packed congregation at Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee. In the speech titled “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” he said, in summary, “All we say to America is, ‘Be true to what you said on paper.’”

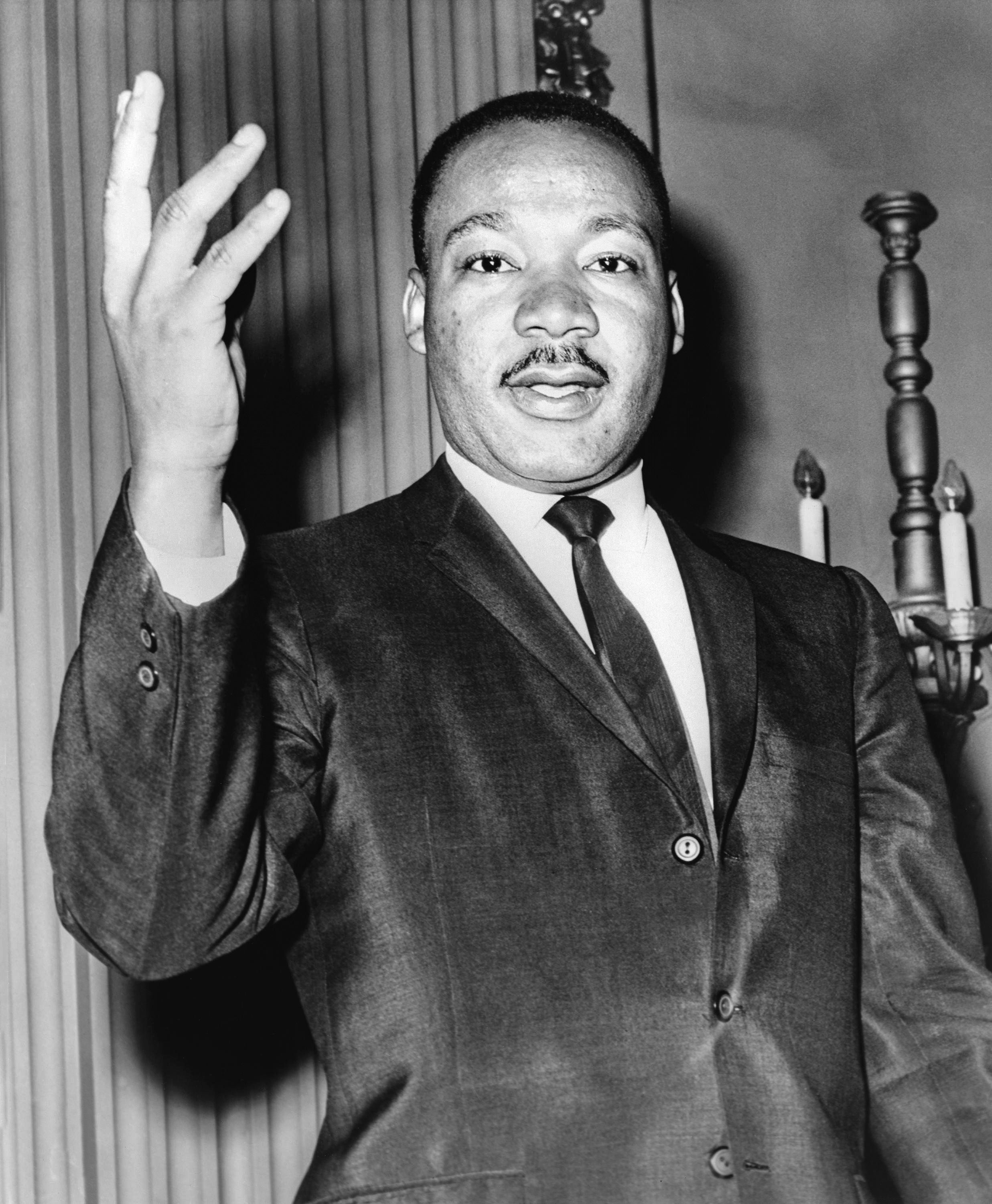

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1964.

This may not be realizable, however, given America’s commitment to the perpetuation of an alleged white supremacy that seeks actively to destroy whatever faux democracy was established in the eighteenth century. If this were not the case then how do we explain the contradictions arising from the way white people are treated in this society, and the very different way in which black people have been and are treated? Thus the question, Will racism ever go away? For it is clear that we cannot have both a democracy and white supremacy. So, we must choose. “Will we continue in the manner we have?” is one possibility. Namely, the brief removal, and then replacement, of the thin veneer that masks the extent of domestic oppression herein. A second possibility is the rise of a vigorous classism not unlike what exists in parts of Europe. The third is the realization that we have to come together, learn respect for each other (consider, for example, the fact that black people have fought in every conflict back to the French and Indian Wars aimed at defending the country), and realize that you cannot put a band-aid on melanoma if you want a functioning democracy.

We also believe our historians have not been honest with us about the adverse societal consequences of white racism in health, education, the economy, political representation, and the administration of justice that is evident in the differential distribution of opportunity along race, class, and gender lines. Nor have they spoken out about how this maldistribution impedes the development of Dr. King’s notion of the “Beloved Community,” a place where one is judged by the content of one’s character, not the color of her skin.

Video courtesy of The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, YouTube

We feel this way because we sense that American society has failed to appreciate the inherent liabilities of the conjoint evolution of extreme partisanship and polarization that thwarts needed change. Clearly, if we do not have some form of cultural change, democracy cannot survive. And, it should be noted, the change must be both substantial and authentic.

Finally, we argue, there is a need to re-examine much of what we have come to believe —especially those myths and their supporting rituals that inform our belief systems. And while we are at it, it might also be useful to examine our customs and traditions, for they too have been subverted by a kind of “white grievance politics.”

More from The Colorado Magazine

“Is America Possible?” The Space Between David Ocelotl Garcia’s and Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Worship

The Women of the WAC Woman Soldiers at Fitzsimons General Hospital

Vision and Visibility Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice