Story

PrideFest: A History of Denver’s Gay Pride Celebration

(30 minute read)

Although no designated landmark pays tribute to Denver’s gay and lesbian history, the annual PrideFest celebration has anchored the community since June 1974. The event’s evolution in Denver reflects social and political changes affecting the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) community through the decades. Not only does PrideFest serve as a time for members and friends of the GLBT community to connect, have fun, demonstrate gay pride, and show support for gay rights; it also commemorates a pivotal moment in gay rights history, the Stonewall Riots.

Gay community life initially centered around gay bars, which became hubs of many social and activist movements in the late 1960s and 1970s. At the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village, police harassment was nothing new. However, according to media and eyewitness accounts, what motivated the police raid on the night of June 28, 1969, was not that the bar patrons slept with people of the same sex, but that they were gender-nonconforming men, or drag queens—men who dress up as women for entertainment purposes. The New York Daily Newswrote that “while ridiculing the effeminate men and drag queens among the patrons, [a]ll hell broke loose when the police entered the Stonewall. The girls instinctively reached for each other. . . . The war was on. The lilies of the valley had become carnivorous jungle plants.” Gay men, transvestites, and lesbians fought the police during riots that lasted six days and, according to author David Carter, sparked the gay rights movement. Following the riots, the first gay rights organizations formed in New York City, then spread across the nation and world. The riots’ first anniversary initiated gay pride marches in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago; three years after that anniversary, the public displays of activism would come to Denver.

Gay rights activists demonstrate at the Democratic National Convention, New York City, 1976.

Because homosexuality was not an open topic for discussion throughout much of human history, its presence in nineteenth-century Colorado went largely undocumented. However, court records and a few Denver newspaper articles addressed the act of sodomy, sometimes called “buggery” or “crimes against nature.” Thomas J. Noel mentioned in a 1978 essay what could have been an early Denver gay bar. He cites an 1885 story linked to an alleged homosexual male leaving “Moses’ Home,” a saloon on Fifteenth and Larimer Streets. Noel also suggests that the demographics of nineteenth-century Denver, with its dominance of young, sexually aggressive males, could have created favorable conditions for homosexuality. He notes that a pioneer Denver physician warned fellow doctors about the evils of “male prostitution” in an 1882 address to the Colorado Medical Society.

In Homosexuality in Men and Women (1914), Magnus Hirschfeld included a letter from an unnamed professor in Colorado. This “Uranian,” or homosexual, scholar wrote:

I know quite a number of homosexuals in Denver, personally or by hearsay. At this moment I can think of five musicians, three teachers, three art dealers, one minister, one judge, two actors, one florist, and one women’s tailor. Parties are given by a young artist of exquisite taste and a noble turn of mind, and some of his homosexual friends appear at these in women’s clothing. Prostitution is not common in Denver; male prostitutes can sometimes be met in the Capitol Gardens, but not a large number of them. . . . [I]n the vicinity of Denver there is a military fort with a force of a few hundred men. Last summer a soldier from there propositioned me on the street in Denver. I’ve heard that this happens quite frequently in San Francisco and Chicago. In all these cases it was difficult to tell whether the soldiers were really homosexual or just prostitutes, or whether they went with the men for lack of anything better. It’s never easy to draw the line, and things are so expensive nowadays that someone could easily be moved to earn a little pocket money in one way or the other.

Not until the twentieth century would Denver have a gay bar that advertised itself as such. Opened in 1939, the Pit operated on Seventeenth Street in the heart of downtown for a short time. After World War II, writes Noel, Denver’s gay bars and the gay community became more organized and more visible. The first such bar, Mary’s Tavern at 1563 Broadway, mostly hosted Lowry Air Force Base airmen, who eventually overtook the bar after repeated run-ins with the police failed to discourage their return and straight patrons began going elsewhere.

By 1949, The Denver Post claimed that the city’s homosexual population had reached an all-time high, thanks in large part to its strong military presence. By 1965, the Armed Forces Disciplinary Control Board made six of Denver’s eight gay bars off-limits to military personnel. That same year, a six-day piece titled “Homosexuals in Denver” ran in the Post, discussing the homosexual as a major problem for the city. The Denver gay publication Out Front Colorado reprinted a condensed version of this article in July 1976 to remind readers of past struggles.

For Denver, a major turning point in gay activism that would help organize what would become known as PrideFest occurred in February 1973. Police used a large bus dubbed “The Johnny Cash Special” throughout the United States to entice homosexuals with the promise of sex and trap them inside, where members of the vice squad would arrest them. In a special operation, this bus patrolled Denver’s Civic Center, a known gay “cruising” area, resulting in the arrest of twenty-four men. This event helped propel disorganized Denver gay men into unified action and helped galvanize the Gay Coalition, which demanded answers and a statement from the police chief. Fed up with police harassment, in October 1973, the newly formed Gay Coalition gathered at a city council meeting, clamoring to be heard. “About 250 of us, angry gays and lesbians, were there,” retired attorney Gerald Gerash remembered in the Rocky Mountain News. “The councilmen were dumbfounded.”

After this event, alliances were built in which tavern owners policed their own establishments and the police became more accepting of public displays of affection between same-sex couples. According to Noel, by the mid-1970s Denver boasted gay publications, fourteen gay bars, three gay churches, several gay bathhouses and apartment houses, a gay motorcycle club, a gay theater, and a gay coffeehouse.

The time was ripe for the first PrideFest. In relation to the gay pride event, the term “PrideFest” was not officially and regularly used until 1990. Before then it went by many different names and bore little resemblance to today’s event. “PrideFest” of the 1970s through the 1980s focused more on marches and a community fighting for the most basic of rights.

Known as Gay Pride Week, Denver’s first “Pride” event took place in June 1974 to celebrate the community’s gains made during the preceding months and to commemorate the Stonewall Riots’ anniversary. In contrast with today’s enormous turnouts, the inaugural event included a “gay-in” at Cheesman Park attended by about fifty. The Gay Coalition Newsletter reported, “Despite interference by the park police who were concerned about the large ‘Gay Pride’ sign installed in front of the pavilion, the afternoon was one of fun, comradeship and pride. ‘Gay Pride’ balloons were given to all and everyone; new friends were made and another step made toward gay liberation in Denver.” No record exists of a pride event in 1975.

In 1976, an event developed that more resembles the celebration of the present day. Formed that same year, the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center of Colorado organized the weeklong event, capped off with a carnival and Denver’s first gay pride parade. Out Front Editor Phil Price wrote in his column:

On Sunday, June 27, Colorado Gays will be presented with a unique challenge and opportunity. A parade, complete with floats and banners, will form at Cheeseman [sic] Park at 2 p.m. It will move down Franklin street [sic] to Colfax, and from Colfax to the Civic Center. The parade will not just be any parade. It will be a gay parade, organized for and by gay people. The success of this event rests entirely in your hands. A few of us can turn out and confirm the straight world’s stereotype that gays are few and far between. Or, we can all come out in a show of strength and numbers that will make the world stand up a notice who we are—and what we want. And just what do we want? To live in a society free from any oppression because of our lifestyles. It’s your choice, the time has come. Come out, or live under oppression.

The 1976 Gay Pride Week started on June 20 with a live show at Civic Center’s Greek Amphitheatre and a carnival at the Hide and Seek, a gay bar in Colorado Springs. The Civic Center show featured Christi Layne and benefited the Gay Community Services Center (GCSC). The Free Spirit Motorcycle Club collected donations. The Hide and Seek carnival raised money for the Colorado Springs Gay Relief Fund, an emergency account for legal, medical, and other help to gay Colorado Springs residents. Three events took place on Sunday, June 27. First the Gay Pride Parade assembled at 2 p.m. at the Cheesman Park pavilion, with many floats, cars, and banners. Another “gay-in” followed at the Greek Amphitheatre, featuring food, information booths, beer, dancing, and a short show. That evening Mike Jefferson hosted a show at the Apartment, a gay bar, with the day’s proceeds benefiting the GCSC.

The June 17, 1977, issue of Out Front detailed, “[T]he week June 19–26 has been recognized as Gay Pride Week. The week-long designation is in remembrance for the Stonewall incident in 1969 in New York City and is reaffirmation of pride and dignity for all gays.” This marked the first time Out Front stressed the reason Pride is celebrated on a national level. A gay carnival, the second annual Gay Day at Elitch’s (which continues today), “A Touch of Class” show, and the parade highlighted the week’s activities. As Out Front documented, many expressed a sense of unity with their gay brothers and sisters and pride at such a large number of gays—an estimated 1,000—striving for the same goals.

Two controversies distinguished this event, the first surrounding the distribution of Coors beer. That same year, Coors was accused of firing employees solely based on their being gay and lesbian. One group of people attempted to smash the keg of beer and keep anyone from drinking it. Several fights ensued, but soon came under control. Price addressed the second issue in his July 4 letter from the editor column, titled “Apathy.” He pointed out that the Denver Police Department was on its best behavior for the event because all the major news organizations were covering it. Take away the cameras and reporters, Price said, and the police showed their true colors by ticketing gay bar patrons the previous month for “standing up while drinking.”

In 1978, the event was called Lesbian/Gay Freedom Week. Price, in his editorial column, had become more militant, challenging all gays and lesbians in Denver and Colorado to attend and make their voices heard. He wrote, in part:

Many local gays have not felt the need to take a strong and open position in Colorado with respect to gay rights since Denver has become, at least in the eyes of the Rocky Mountain News, a “homosexual haven.” We have no problems here, we’re so well accepted in our little haven, some would say, that we don’t have to bother ourselves with all this gay rights stuff. Wrong. To those Colorado gays who have taken refuge in our happy gay haven, you’d better set your strawberry daiquiris and suntan oil aside for a while and wake up to what’s going on in this city. The Anita Bryant syndrome is alive and well in Denver, your home. We don’t have a gay rights ordinance in Denver to be repealed. Just exactly what form this group’s anti-gay crusade will take has not yet come to light. But if and when it does, I only hope that there are enough Colorado gays concerned about their futures to stand up and be counted. If not, we might as well prepare ourselves for one big gay holocaust.

In 1977 singer Anita Bryant led a successful campaign in Dade County, Florida, to repeal anti-discrimination laws. She led several more campaigns across the country. in 1978, she was on the minds of Denver marchers.

Anita Bryant, a pop singer in Dade County, Florida, was a polarizing figure instrumental in repealing discrimination laws protecting individuals based on sexual orientation. An ad in the Rocky Mountain News, reprinted in Out Front, represented the threat to which Price was responding.

Price’s message might have had the impact he’d desired. In his column, he reflected on the 1978 event as one of the best, the main difference being the attitude with which most gays approached the event. Gone in that year’s trek from Cheesman Park to Civic Center was the carnival-like atmosphere of past celebrations, replaced by self-assertion and protest. The emphasis on “marching and not paradeing [sic] demonstrated that, yes, the fun and games were over and that Colorado gays were ready to get serious about the struggle for their full share of rights.” Price also observed that many more lesbians joined in the march than in previous years and that the parade showed unity and strength within the gay and lesbian community.

The activist tone continued in 1979. The march followed the same path and drew about 1,500 gays and lesbians. The Saturday night before the parade, about 250 people gathered for a candlelight vigil commemorating the Stonewall Riots’ tenth anniversary.

An unforeseen disease would threaten an entire community during the 1980s, a decade of fighting for lives as well as rights. But before the fear of AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) engendered a new fear of homosexuals, things began to get back to normal for the event dubbed Pride 1980, with the theme “Celebrate in Unity.” The march was again called a parade, featuring floats, cars, and performers. For the first time, a huge warehouse party boasting a state-of-the-art sound system and laser show took place the night before the festival, a tradition continued in today’s PrideFest with a party at Tracks Nightclub. After the parade, the festivities moved back to Cheesman Park for a beer bust and picnic. Gay Freedom Week of 1981 took on a more political vibe, with speakers at the rally after the parade claiming that no sympathetic city councilperson or state representative or senator would champion legislation specifically protecting gays.

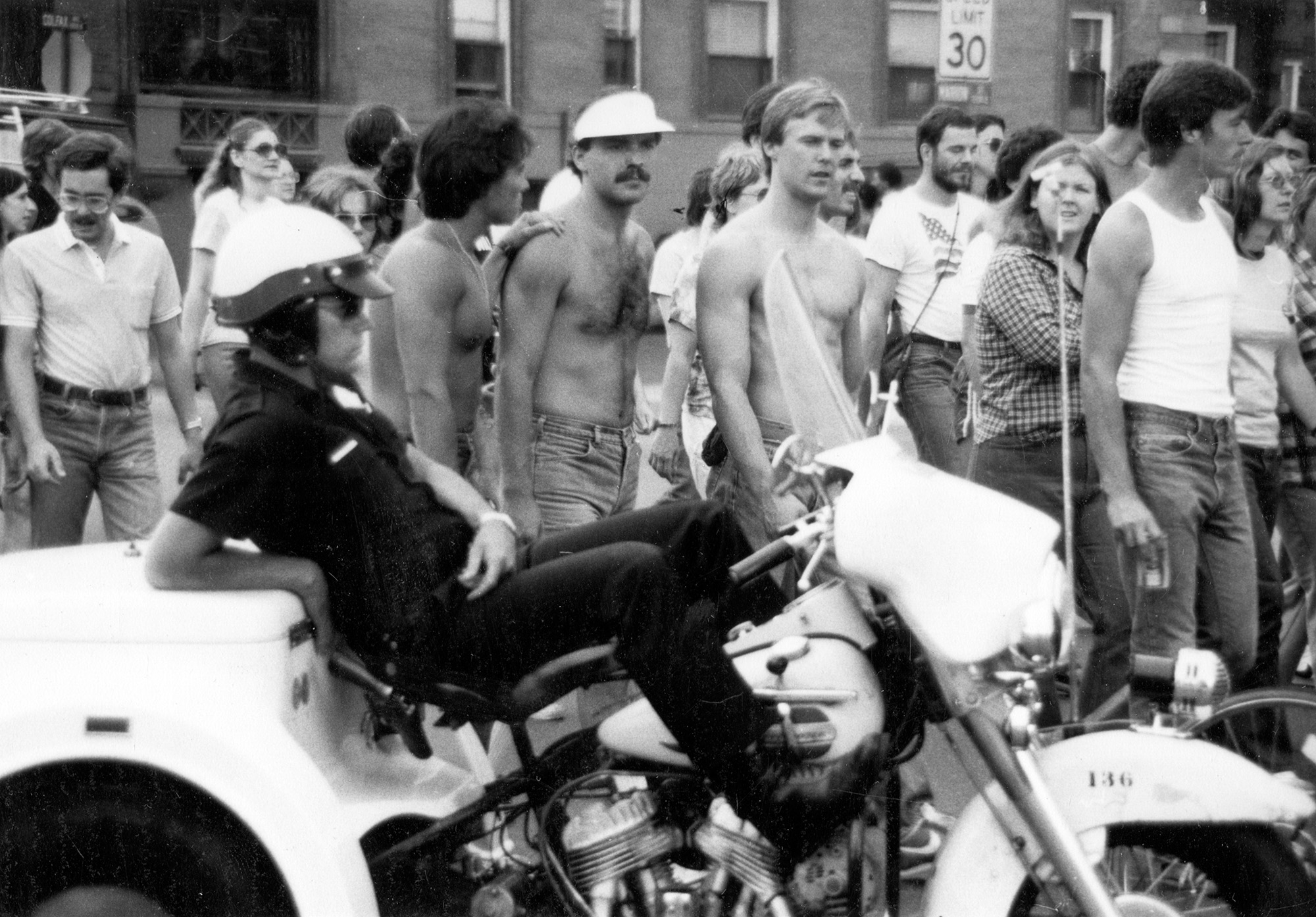

Although the first years of the parade prompted tense relations between police and marchers, this scene shows a much more relaxed climate by 1981.

In 1982, the event—known as Gay/Lesbian Freedom Week—put forth a festive parade. In its coverage, Out Front discussed the opening of the first all-gay bookstore, Category Six, which operated from an old residence at Eleventh Avenue and Ogden Street for much of its decades-long existence; the name Category Six was taken from the Kinsey scale, with 0 representing exclusively heterosexual tendencies and 6 indicating exclusively homosexual tendencies. Also that year, Out Front asked readers what Pride meant to them and published their responses, including one from David Carrasco: “I’m really looking forward to Gay Pride Week. To me it is a way we are expressing one voice that we are one people. To me it is very important that the world not be ignorant any more—that gays are people.” Carrasco had been discharged from the military for being gay and was looking for secretarial work. A twenty-one-year-old cook from Fort Morgan responded, “Out in Morgan there are no gay bars or gay people. Things are kind of in the closet. This is the first time I’ve been to Denver in over two months.”

In 1983, bad weather almost cancelled the event. About 1,000 braved the rain to travel the traditional path from Cheesman Park to circle the capitol, but then the parade returned to the shelter of Cheesman Park’s pavilion. Also at this time, articles about gay sex and AIDS appeared in Out Front. “Overwhelmed!” is how Pam Young of San Francisco, co-chair of the 1984 Pride Week Parade, told Out Front she felt upon seeing 2,000 marchers—the largest crowd to date—pouring into Civic Center’s Greek Amphitheatre that year. “In San Francisco, we have bigger parades, but here, everybody marches.”

In 1985, AIDS hit the gay community hard. Everyone was losing friends left and right to a disease no one saw coming, prompting the festival to adopt the theme “Alive with Pride in ’85!” In Out Front, organizers deemed the turnout for the two-day festival the largest and most colorful in Colorado gay history. The first carnival-type event took place in the Tracks Nightclub parking lot; the original Tracks was eventually torn down and replaced with lofts by Coors Field. Mayor Federico Peña issued a proclamation declaring June 27 Gay Pride Day in Denver.

No money existed for a 1986 event because the organization that usually directed it had collapsed. Nevertheless, about 600 people assembled at the Auraria campus to celebrate what local newspapers for the first time called “PrideFest.” No parades took place in 1985 or 1986.

In 1987, AIDS took center stage at PrideFests around the country. Although Mayor Peña addressed the crowd and thanked the gay community for having made the critical difference in his election, only about 500 people attended Denver’s event, themed “Out of the Closet and Onto the Streets.” Such stigma surrounded homosexuality that people didn’t want to appear at the event for fear they would be seen or photographed there. “This year means more than any other year in light of the AIDS epidemic. It’s a time for every gay and lesbian person to show their strength and unity,” said organizer Ron Hillstrom. Gays had suffered a backlash because of AIDS, he told the Rocky Mountain News, pointing to a new law requiring the Colorado Department of Health to collect the names of people who tested positive for exposure to the disease; it was unclear who could access this list or how secure it was.

Parents FLAG (today’s PFLAG, or Parents, Family and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) was founded two years before Denver’s first Pride event. The simple act of a mother, Jeanne Manford, publicly supporting her gay son in the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day March led to the group’s formation.

The turnout rebounded in 1988, the first time the event, this year called the Gay and Lesbian Pride Celebration, took place in conjunction with the Rocky Mountain Regional Rodeo; the Colorado Gay Rodeo Association still hosts the gay rodeo but it takes place in Golden, not as part of PrideFest. Out Front mentioned the police and gays meeting in 1988 to discuss the elevated occurrence of “fag-bashing,” another result of the negative impact of AIDS on the gay community.

The Rocky Mountain News wrote that a surprisingly small segment of Denver’s homosexual community turned out on Sunday, June 25, 1989, to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. Steve Konda, a vice president for the Gay and Lesbian Community Center of Colorado Inc., estimated that as many as 300,000 gays and lesbians lived in the metro area. Though event organizers expected about 3,000 people, only about 250 showed up at the Civic Center rally. “Quietest rally I’ve ever seen,” observed one man in his early thirties. “This is a pride rally?” asked another. One man in his mid-thirties paraded through the crowd with a six-colored “rainbow” flag that symbolizes gay pride and unity. An employee of the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant, he declined to give his name, citing a potential threat to his security clearance. “It’s sad that there is still this fear of losing jobs and family and friends,” he told the News.

The 1990s brought an end to the silence and a new urgency among the GLBT community, along with legislation that alternately took away or extended the rights of homosexuals statewide. Gay pride celebrations were officially named PrideFest in 1990, though information about this and the following year’s events remains obscure. Not so for 1992, when Colorado for Family Values (CFV) fired a direct shot at the gay community by collecting thousands of signatures to bring an anti-gay amendment before Colorado voters. CFV formed in 1991 in Colorado Springs to oppose gays’ attempts to secure protection from discrimination. The gay community showed up for the fight, and PrideFest attendance ballooned. The Newsreported, “In perhaps the largest rally ever for homosexual rights in Colorado more than 30,000 people turned out Sunday to protest the anti–gay rights Amendment 2 that will be on the November ballot.” The amendment to the Colorado constitution would forbid cities and other political subdivisions from according protected status based on sexual orientation. “It’s the most negative thing tried by the right wing in the entire country,” said Judy Harrington, campaign manager of Equal Protection Ordinance of Colorado, the statewide group campaigning against the amendment. The ballot initiative would repeal laws in Denver and other communities that specifically protected the civil rights of homosexuals. Opponents of the initiative said it would open the door for discrimination based on a person’s sexual orientation. Eleven-year-old Justin Hribar, who marched in the parade, told the News he considered the parade “a pretty neat idea because people can come out and be proud that they’re gay and stand up for their rights. It’s unfair to not give them any rights. They’re people too.”

If Amendment 2 proved the main topic of PrideFest 1992, it became more so in 1993. In November 1992, voters passed the amendment by a majority of nearly 54 percent. Known almost overnight as the “the hate state,” Colorado became the target of a nationwide boycott from some visitors and conventioneers. The most prominent chants at PrideFest 1993 denounced the amendment. PrideFest director Tom Ervin informed the News that about 40,000 people from more than 100 organizations participated, topping the previous year’s record.

More than 25,000 turned out for PrideFest 1994, but attendance swelled to more than 60,000 in 1995, with the theme “From Silence to Celebration.” The fate of Amendment 2 weighed on almost everyone’s mind; that fall it was going before the U.S. Supreme Court, where the nation’s highest judicial body would strike it down. Despite the political backdrop, PrideFest went mainstream with the participation of organizations such as Norwest Banks, Target, Ticketmaster, and the Denver Public Library. Organizers used these endorsements to underscore the growing acceptance of gays and lesbians, noted the News. Larry Gross, author of Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men and the Media in America, says the shift toward the mainstream came in the 1990s when the gay-friendlier Clinton administration took office and AIDS came under some control. Also in 1995, chronicled the News, Denver Mayor Wellington Webb addressed the crowd: “We join in the fight for gay and lesbian rights both before and after Amendment 2. The future of Denver must include you. You will be at the table, but not only are you going to be at that table, you are going to help set it!” The crowd cheered.

At least 50,000 attended PrideFest in 1996. The next year, 57,000 celebrated, with 220 merchandise and information booths and fifteen food-and-beverage vendors. Entertainment took place on two stages over four hours and featured twenty-two acts. Reggie Caldwell, event co-manager, told the News, “When the first [official] PrideFest was organized seven years ago, we never dreamed we could support such a following. Even on a national scale, we are considered big.” Co-manager Carol Hiller added that each year the event raises money for the Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Community Services Center of Colorado, but the most important part is “watching tens of thousands of people coming together to celebrate who we are, and to do it with pride is great.” The Denver Post reported that Keith Boykin, executive director of the Black Gay and Lesbian Task Force and the highest-ranking openly gay person in the White House during Clinton’s first term, garnered much attention as his voice carried over the crowd: “I’m here to tell you today that there is nothing more important, powerful, persuasive or beneficial than to come out and be open and honest about who you are.”

The 1998 parade had more than 100 contingents from at least five states—as the News called it, the largest Pride parade in the region and among the top ten in the country. PrideFest 1999, the thirtieth anniversary of the Stonewall Inn riots, attracted an even larger number of people. Connie Hunt of Littleton, who marched with Parents, Families and Friends for Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) said it best in the News: “My son is gay and we have a choice as parents either to support our kids or lose them. I believe in justice and equality for everyone, and I don’t think your orientation on anything should matter.” This year also brought something new: two people with hand-lettered signs urging homosexuals to “repent sin” and warning, “God’s judgment is near.”

With the new millennium came wider acceptance and new social ideologies that would change the way gay men and women celebrate their diversity. PrideFest had always involved both having fun and showing the world that the vibrant GLBT community takes its fight for rights and recognition seriously. PrideFest 2000 showed the world another major change that would strengthen as the years progressed, a designated “family area” catering to couples with children in tow. The sectioned-off area, where kids could paint, play, and eat, had signs warning “drug, alcohol, hate-free zone,” as well as signs prohibiting smoking.

By 2001, PrideFest attendance had broken the 100,000 mark. The Two Spirit Society, an American Indian gay and lesbian group, served as grand marshals that year. “Two spirit” is an American Indian term for gays or lesbians, who are honored and respected by most American Indian cultures. Nicole Benson came to PrideFest from the University of Northern Colorado with three lesbian friends. To the News, she described it as her favorite day of the year. She said she and her friends often felt isolated from the rest of society, but PrideFest represented the one day they didn’t feel that way. PrideFest 2002 saw another all-time-high attendance and booths offering everything from jewelry to PrideFest apparel to artwork—and for the first time, volunteers seeking signatures for legislation affecting the gay community and distributing flyers and other information supporting the gay and transgender community.

PrideFest 2003 marked a significant anniversary: Thirty years before, members of Denver’s gay community had gathered before city council. The event now had an operating budget of $225,000 and had expanded to include 200 exhibitor booths, twenty-four food stands, two entertainment stages, a dance area, and more than 100,000 participants. According to the News, parade announcer John Schlegel said in mock surprise, “My God, I remember when gay bars were dark little holes in the wall and now everybody has a patio. What’s happening?” He also remembered a gay bar a few blocks away where Denver police used to arrest drag queens and a time in the 1980s when he wanted nothing to do with the smaller parades that were precursors to PrideFest. Also this year, Mayor-Elect John Hickenlooper flew home from vacation in Ireland one day early to attend the event and thank everyone for helping to elect him. “One of the things I’m most proud of in Denver is that we have chosen to define ourselves not in terms of words like ‘tolerance’: we talk in terms of words like ‘embrace,’” he said.

One of among 170,000 attendees in 2004, Denver resident Shad Gray told the Post it is important to remember the origins of why the community celebrates Pride. The theme for 2005, “Equal Rights—No More, No Less,” spoke to the more political nature than that of other recent PrideFests. The month before the event, Governor Bill Owens had vetoed a bill that would have added sexual orientation to a list of protections from workplace discrimination. “Owens’ veto is one of the reasons why we chose our theme,” said Michael Brewer, a festival organizer and director of public policy at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center of Colorado.

The American Veterans for Equal Rights, Rocky Mountain Chapter, sponsors the Colorado LGBT Community Color Guard, the nations first and only regulation LGBT color guard. Active, reserve, and veteran members of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force make up the guard.

For the rest of the decade, attendance generally rose. In 2009, PrideFest began starting on Saturdays instead of the traditional Sunday. Saturday, “Family Day,” allowed families to enjoy a more low-key festival with a kid-friendly atmosphere before the crowds of Sunday converged. Sixty-nine-year-old James Steed surveyed the crowd and recalled when Denver’s gay community lived in the shadows, police harassment at gay bars occurred commonly, and few people would risk losing their jobs by revealing their sexual orientation. “This is so out in the open,” he mused to the Post. “There is a good, positive attitude from the police; that is certainly a change.”

The theme for PrideFest 2011, “These Colors Don’t Run,” honored the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT), which officially ended in September of that year. Representing the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network, an organization that worked to abolish DADT—a policy under which more than 14,000 gay and lesbian members of the U.S. military had been discharged since 1993—Major Mike Almy served as grand marshal of the parade. Among the record-breaking 300,000 at 2011’s PrideFest were hundreds of children. Denver’s PrideFest has become one of the country’s most family-friendly Pride events. Almost a third of Denver’s homosexual couples have children, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

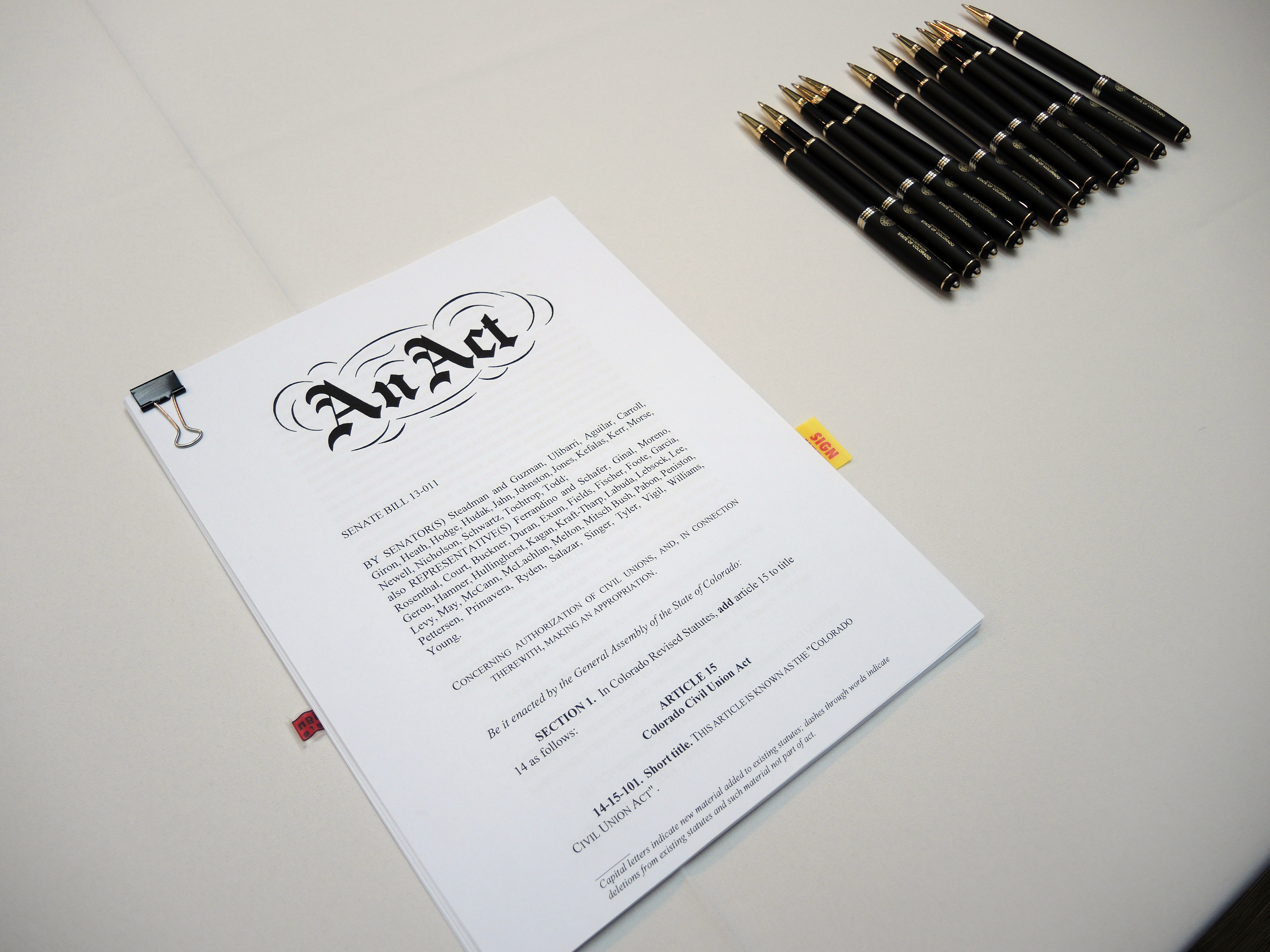

Governor Hickenlooper signs the historic Colorado Civil Union Act into law. Around him are Reps. Joann Ginal and Sue Schafer, Sen. Pat Steadman, and Speaker of the House Mark Ferrandino.

A central social event for Colorado’s GLBT community, PrideFest helps fulfill a need that gay bars once served. Before the Internet, the only welcoming places gay people could frequent were gay bars. There they could meet, hang out, and strategize with one another. Gay bars still exist for many of those same reasons, but now they mainly function as places to have fun. Websites and online chat rooms have lessened the role of gay bars as social forums.

An enduring trend is PrideFest’s ability to spread awareness of political issues that have long-term effects on the gay community. The biggest topic of the moment has become civil unions. PrideFest 2012 found many attendees disappointed in a system that had let them down. In May 2012, the Colorado legislature twice rejected a civil unions bill. However, disappointment will not cloud PrideFest 2013. For gay-rights proponents, on March 21 of this year, a journey that began on Valentine’s Day 2011 outside the state capitol came to a victorious end in the History Colorado Center. With hundreds looking on and a vintage “Welcome to Colorful Colorado” sign as a backdrop, Governor John Hickenlooper—who had requested that the signing occur at the History Colorado Center—signed into law the Colorado Civil Union Act. Although civil unions don’t offer full marriage rights, Colorado is now the eighteenth state to grant comprehensive relationship recognition to same-sex couples. In June 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court should rule on two cases that could affect marriage equality, considered the next civil-rights goal among Colorado gay lawmakers and activists: the first case being California’s voter-approved ban on gay marriage, Proposition 8, and the second being the 1996 federal Defense of Marriage Act. Even if these rulings do not favor the gay and lesbian community, Coloradans will surely celebrate the state’s civil unions victory this year at PrideFest and perhaps, after twenty-one years, the demise of its “hate state” reputation.

Participants at the 2016 PrideFest celebration honored the victims and survivors of the June 2016 attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, a tragedy that had happened just days earlier.

No matter the social or political climate, two persistent themes have defined PrideFest throughout its existence in Denver: unity and visibility. PrideFest represents the one day a year when every gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender Coloradan can feel accepted and not have to worry about what others think. PrideFest shows society the GLBT community’s strength in numbers and demonstrates how it can support and make a difference in the lives of its members. For the many people still in the closet who don’t feel safe expressing their sexual preferences, PrideFest affords an opportunity to get out and get lost in a crowd of people who share a common experience.

An excellent source for more information about the GLBT community in Denver is the Terry Mangan Memorial Library located at The Center, 1301 East Colfax Avenue. See also current and back issues of Out Front Colorado, one of the nation’s oldest continuously running, independently owned and operated GLBT newspapers. Instrumental in researching this article were Thomas J. Noel’s essay “Gay Bars and the Emergence of the Denver Homosexual Community,” The Social Science Journal, vol. 15, no. 2 (1978): 59–74; David Carter’s Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004); Jonathan Katz’s Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1976); and archive issues of the Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post.

— Aaron Marcus, Photo Studio Manager, History Colorado, Collections and Library Division