Story

The Year of the Ethicist

When the Covid-19 pandemic exposed public health shortcomings and deadly racial inequities, it sparked a new public conversation about our priorities. The hard days and difficult decisions of 2020 propelled new ways of thinking about the health and wellbeing of our whole society, including what a “right to health care” really means.

Editor’s Note: How will 2020 go down in history? In the Hindsight 20/20 project from The Colorado Magazine, twenty of today's most insightful historians and thought leaders imagine themselves in 2120, looking back on 2020 and sharing their visions of how that year will stand the test of time.

The year 2020 was the beginning. The beginning of conversations we still have today: questions about who lives and who dies, about where we spend our money and time, and about how we treat our neighbors. Those conversations, which seem so routine today, wouldn’t have happened without the disruptions of 2020. They needed a catalyst, and together the Covid-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement served that role.

Covid-19 raised difficult questions at every turn. How is personal liberty weighed against collective safety? How are scarce resources allocated to care for sick people? How is the safety of research participants balanced with the urgent need for a vaccine? Would consideration of “quality of life” result in the marginalization and dehumanization of people with disabilities? Terms like triage and vaccine distribution became widely understood and important in the decades to come.

At the direction of Governor Jared Polis, members of the Colorado National Guard Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear and high-yield (CBRNE) Enhanced Response Force Package (CERFP) assisted in performing COVID-19 testing at a state veterans home in Aurora, Colorado, April 29, 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic seems almost quaint when you remember the leishmaniasis that slowly crept into the United States in the 2040s, the novel influenza that killed tens of millions in the 2080s, and the “invincible strep” that spread last year. But Covid prompted people to really assess how we should respond to new diseases. Each time a new threat erupted, we asked the questions again. We never agreed on the answers, but, ever so slowly, people learned to openly talk about what tradeoffs we were willing to make—and who has the right to make tough decisions.

We began to ask these questions not only with each new disease, but with each year’s health care budget. Without 2020, the amount of money we spent on health care would have continued to increase indefinitely. While last year’s invincible strep revealed continuing disagreement about what we should do in a crisis, we’ve realized that a fair process for deciding how to respond might be more important than the response itself.

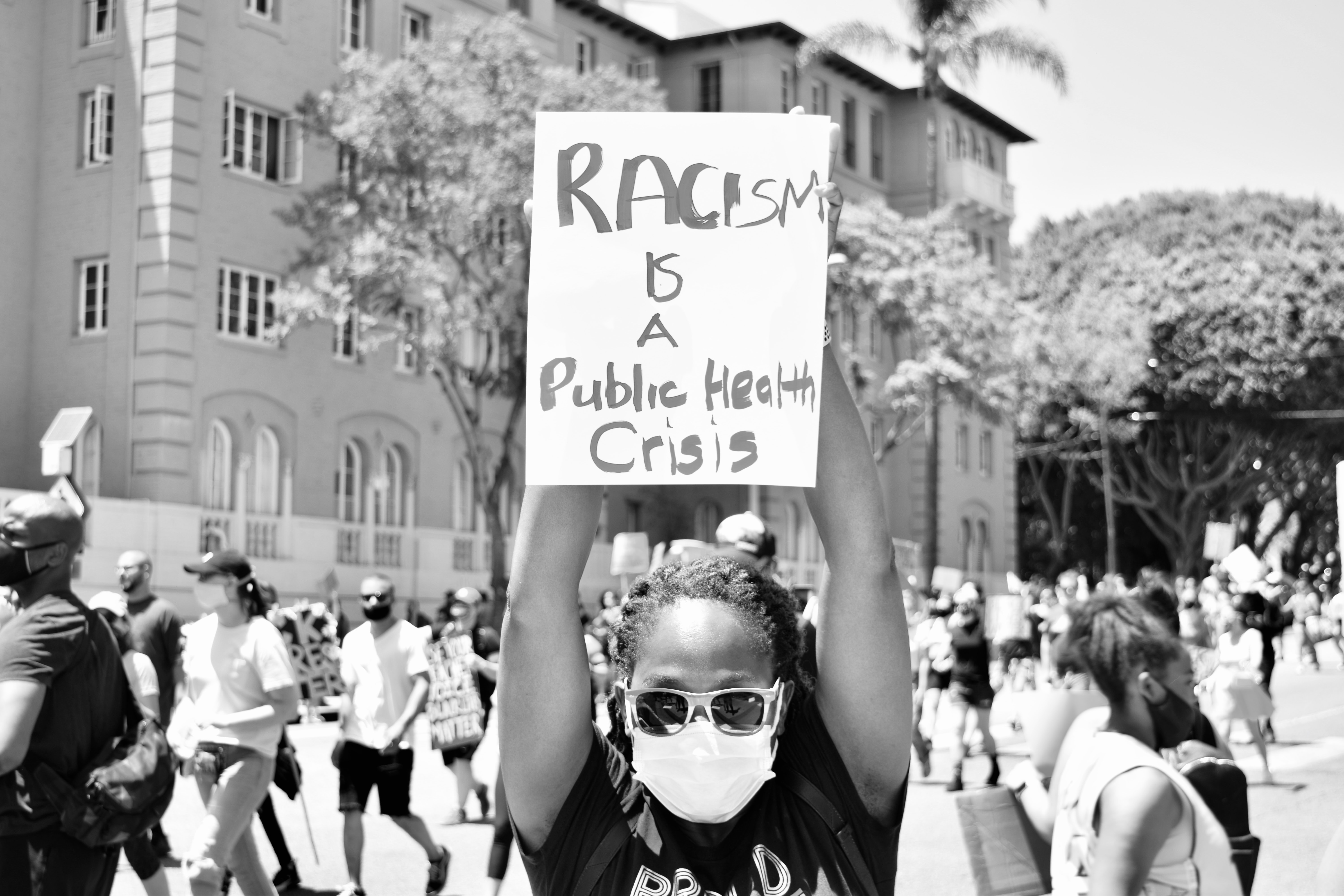

The other major event of 2020 was the Black Lives Matter movement. While today, most people remember BLM for its reform of policing, its effect on health care was no less profound. Covid-19 disproportionately affected those who were Black, Indigenous, and people of color because they had poorer access to health care before and during the pandemic. While some policies tried to address this form of discrimination during the pandemic (by giving priority access to treatments and vaccines to people from disadvantaged communities), it was only in the reckoning afterward that people started to ask, “Why did this happen?” and to realize that crises are a difficult time to correct centuries of injustice. BLM had staying power: Policymakers responded, leading to our modern system of universal health care. By the 2050s, life expectancy rates among races equalized, and the dangerous idea that race was the cause of disparate health outcomes was extinguished.

Black Lives Matter protestors took to the streets demanding reformation of the social injustices that plagued American society.

Those who lived through 2020 often suggested the year would be remembered for its death and destruction. But with the hindsight of history, its lasting impact has been on the conversations we have every day. We wouldn’t have learned to talk about difficult health policy questions openly and honestly. We wouldn’t have experienced how our decisions about health care have real life-or-death consequences for real people. Twenty-twenty was a costly year, but without it, the last century would have been much poorer.

More from the Hindsight 20/20 project in The Colorado Magazine

Saving the “Soul of the Nation” Since the day record numbers of Americans elected Joe Biden as their president, historians have been writing the record of the Trump Era and the fractures his presidency exposed—and how Americans charted a path forward.

American Studies 102: Survey of 21st Century US “Race” Relations A twenty-second-century American Studies professor looks back at the antiquated notion of “race” that prevailed in 2020, when high-profile incidents of anti-Blackness sparked the War of Reckoning and, ultimately, the Great Reconciliation.

Looking Backward: Lessons from a Pandemic If we take a backward glance at 2020 from the standpoint of 2120—never mind how we got here—what do we see? And what perspective have we gained in the century since? Colorado’s State Historian takes a moment to ponder some lessons learned.