Story

Piecing Together the Past in the Era of “Shelter at Home”: Historic Ceramics from Pueblo’s Fariss Hotel

Ceramics are an amazing resource for understanding the past, as so much information can be packed into just a single piece. We can understand manufacturing methods based on where it came from; we can study class and economics based on the original cost of the dishes; we can even delve into matters of identity as evidenced by the conspicuous display of fine dinnerwares.

For three years we’ve been working on the El Pueblo/Fariss Hotel artifact collection, today in the Emery Archaeology Laboratory at the History Colorado Center. The Fariss, built in 1882, was found quite by accident, as it stood over the original site of El Pueblo, a mid-nineteenth century adobe trading post that once stood on the banks of the Arkansas River and, in its day, was on the border between Mexico and the nascent United States. It’s very common to see layers of habitation in archaeological sites, and when we have successive sites on top of each other we call it a “multi-component site.” In this case, the layers of occupation are from an evolving American city that’s unique in its history and identity.

Most of the artifacts from the El Pueblo/Fariss site come from the Fariss Hotel itself. The hotel generated exponentially more material culture deposits than the trading post. One of the most dominant is ceramics: pottery, china, dinnerware, crockery. Mostly mass-produced for a global market, ceramics have been an important artifact type since the emergence and spread of European powers nearly 500 years ago.

So, given the times we’re now living in, I’ve been spending shelter-in-place nerding out on the ceramics recovered from the Fariss Hotel—boxes stacked in my dining room and broken sherds of white ware spread across the table. The hotel bought lots of ceramics, both for the dinner table and for toilet furnishings for the guests. I’ve never seen so many soap dishes in one place in my life. Hotel ceramics were specifically made for use in such institutions, and needed to be more durable than what families would have had in their homes.

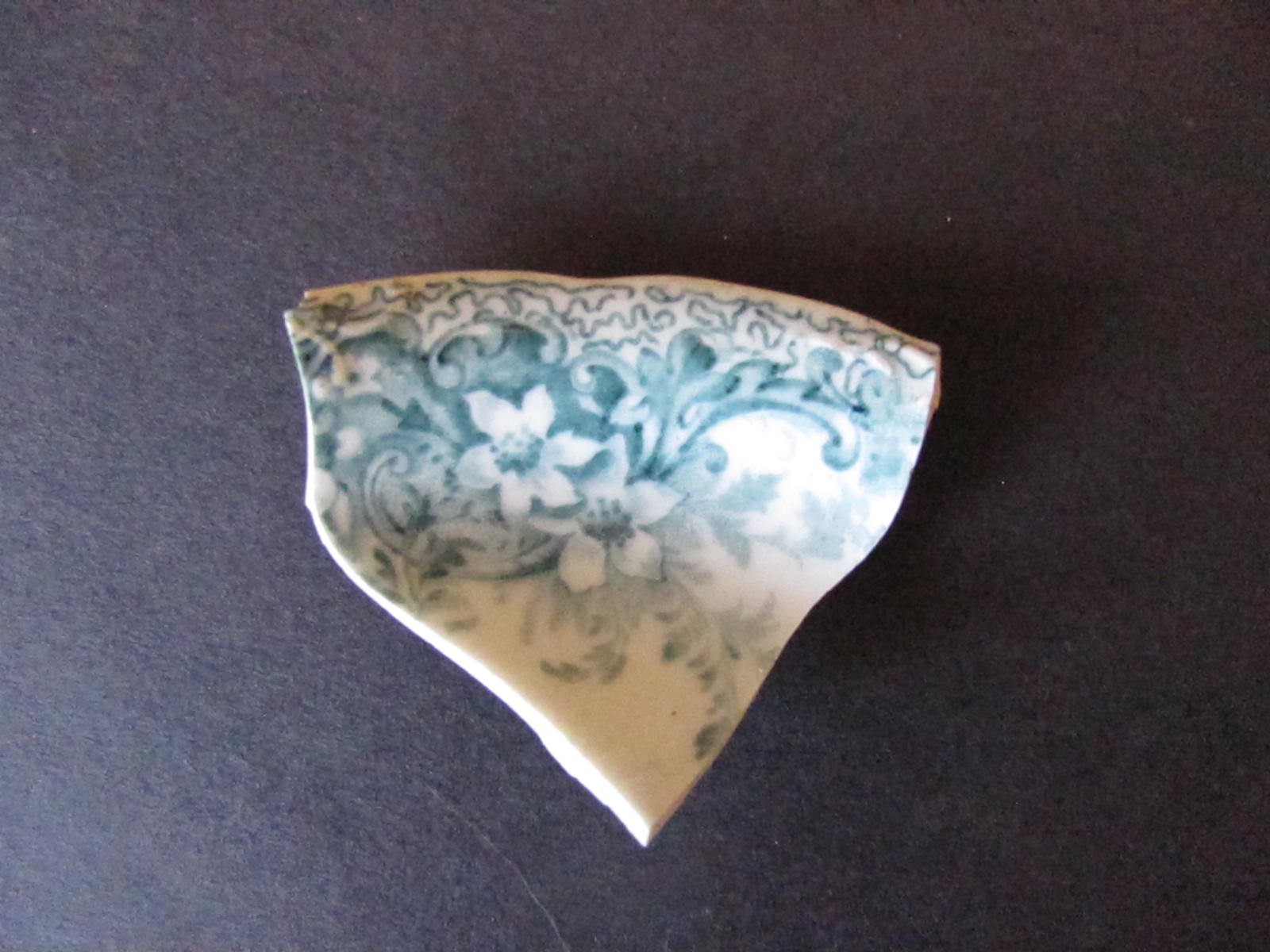

A piece of pottery holds quite a few clues for a researcher. Some can be traced through their designs or decoration. For instance, many companies that manufactured transfer-printed wares had very specific designs that were unique to them, as well as were the evolution of the colors. We’ve found a handful of sherds from transfer-printed wares at the Fariss, and they may have been decorative pieces at the hotel, or heirlooms curated by people who lived on site after the hotel closed in 1915.

As the bulk of what we’re dealing with are “hotel wares,” much of what we’re seeing are undecorated whitewares, or ironstone. While individual sherds of a broken plate may not tell us much, sometimes we get lucky and find a maker’s mark. A “maker’s mark” is the stamp a pottery maker placed on the bottom of their pieces to indicate who made them. Maker’s marks varied not only from company to company, but a company would also change its unique marks through time. Some marks or stamps were even specially created to indicate a new pattern or commemorative run of something.

Researching maker’s marks can be frustrating, particularly for sites in the American West. Much historical research has focused on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century ceramics: the cool yellow wares or tin-glazed delfts you might find at historical sites on the East Coast like Jamestown or Monticello. It’s only recently that many historical sites in the West have been thought of as sufficiently historic, so the artifact research doesn’t always extend into the twentieth century.

You can use antique buyer’s guides to begin basic identification of historic ceramics, but these books and websites have their own challenges, not least of which is that not all antiques are created equal. What’s fashionable to collect today may not be fashionable tomorrow, so there are gaps as to what collectors will write about. Also, antique dealers and collectors aren’t always interested in the same things archaeologists and historians are interested in, so further research is often needed. Luckily there are many resources, although given the necessity of pictures they can be expensive to produce and to procure. In addition to some of the articles cited at the end of this post, there are journals such as Ceramics in America devoted to the subject, as well as books by glorious nerds who are as infatuated with a well-turned piece of stoneware as I am.

So far, I’ve identified eight different marks on undecorated white dishes including plates, saucers, bowls, mugs, and platters. We also have decorated ceramics, especially small dishes called “butter pats” that held butter for your bread. Many of these marks came from potters in East Liverpool, Ohio. Ohio came to dominate the national ceramics market in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, so any well-respecting hotel would have procured their ceramics from there. Around the turn of the century, American pottery and ceramics manufacturers—some started by the English ceramics companies and potters—emerged as high-end, desirable manufacturers of tablewares. Before that, it was the English potteries—Staffordshire, Wedgewood—that dominated the idea of quality ceramics. We see this same evolution in the Fariss Hotel ceramics. The earliest are from English manufacturers, and as the hotel approached the turn of the twentieth century, they began to acquire American manufactured ceramics.

In many ways, the Fariss was on trend. This, coupled with the analysis of other artifact types, suggests that the Fariss was building a very particular identity—today we’d call it a “brand”—to entice a specific kind of visitor to Colorado. Glass bottle analysis coupled with a look at the ads placed by the hotel suggests that the Fariss was part of the health and wellness trends of the state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A large percentage of identified bottles were medicines, often used for treating chronic illnesses. An analysis of faunal remains shows that a high percentage of the meat cuts came from lamb, mutton, and bison. All of this indicates that the Fariss may have been marketing itself as a place to experience the indulgences of “the West” as opposed to other high-end hotels that imported meat and other foodstuffs from the more sophisticated coasts.

In other words, this hotel in Pueblo was styling itself as a destination. It was fashionable to stay there as you traversed the West and this new state of Colorado.

We still have a lot of work to do on the artifact analysis. The excavations of the 1990s and early 2000s yielded 100,000 artifacts, most of which date to the Fariss Hotel era and not the El Pueblo era. But this analysis is giving us an extraordinary view into the city of Pueblo at the turn of the twentieth century. This site probably would have never been excavated if it wasn’t suspected that the fort lay underneath it, and we’re fortunate that another generation of archaeologists didn’t see the Fariss deposits as just “over burden” and chuck it out to get to the good stuff. While the mysteries of the El Pueblo trading post are the heart of the site, the Fariss is the bones— helping give us substance to the past.

A note on ceramic types

Ceramics are often identified by their “body,” or what the interior of a sherd is made of. If you broke your favorite mug, and you looked at the raw, broken edge, that’s the “body.” All ceramics are made of fired clay, but the level of firing produces very different types of ceramics. We call this “vitrification,” and the more vitrified the more glasslike the ceramics become.

On one end is earthenware. Earthenwares are low-fired, so the least vitrified. The lowest fired would be indigenous or locally made ceramics. These are generally described as “coarse” and can have large grains of clays as well as “inclusions” such as grog, which is pieces of fired vessels that have been ground up and added to a clay mixture to give it a little more heft.

Next we have refined earthenwares. This is the ubiquitous “whitewares” that litter Euro and Euro-American sites across the globe. Whiteware “body” can be difficult to differentiate from porcelain or stonewares for many nonspecialists. The best way to tell it apart is to lick a broken edge or an area without glaze. The porous nature of earthenware will stick to your tongue. (However, bone is also porous, so it will stick to your tongue as well.)

Ironstone emerged as an economical answer to the need for very sturdy ceramics for institutions and businesses—like hotels. These are more vitrified earthenwares, often very thick-walled vessels that were marketed as “ironstone” to give the impression of durability. This is what we see most often at the Fariss Hotel. Despite the “ironstone” label stamped on the base of a ceramic piece, the body is often a refined earthenware, although it can resemble stoneware or even poor-quality porcelain.

Next are stonewares. The iconic salt-glazed jug or crock is emblematic of this kind of ceramic. These were often glazed or slipped, and were fired at a high enough temperature that they were non-porous and suitable for storing liquids and foods. Many people refer to the dark brown jugs as “Albany slip,” but it’s only true Albany slip if it comes from the Hudson River Valley region of New York state. Otherwise, it’s Albany “style.”

On the far end of the spectrum is porcelain. Porcelain is the most highly vitrified of all ceramics, becoming almost glasslike. This allows porcelain to be very strong, even as its walls may be thin and delicate. Very fine porcelains are even translucent. When porcelain exported from China first hit Europe in the sixteenth century, people went wild for these beautiful vessels. European potters, in turn, went wild trying to emulate them, experimenting with new clay formulas and different styles of glaze to mimic the lustrous quality of Chinese porcelain.

Sources

William Gates and Dana Ormerod, “East Liverpool Pottery District: Identification of Manufacturers and Marks, 1840–1970,” Historical Archaeology 16 (1982): 1–358.

Adrian Myers, “The Significance of Hotel-Ware Ceramics in the Twentieth Century,” Historical Archaeology 50 (2016): 110–126.

Andrew Popp, “‘The True Potter’: Identity and Entrepreneurship in the North Staffordshire Potteries in the Later Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Historical Geography 29 (2003): 317–335.

Patricia Samford, “Response to Market: Dating English Underglaze Transfer-printed Wares,” Historical Archaeology 31 (1997): 1–30.