Story

Four Times Colorado Women Got There First

Women’s history is unfortunately often overlooked or underplayed, which is why it is so important to recognize important women throughout history. Colorado women have long been proud pioneers in various fields. Here are four incredible Colorado women who accomplished great things, and got there first.

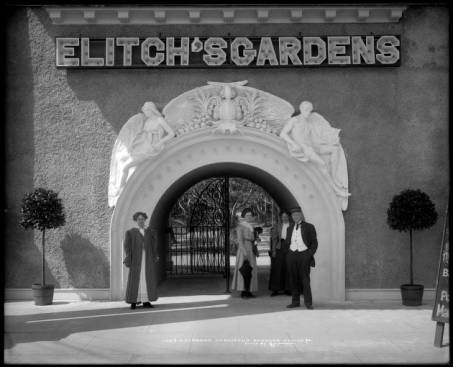

#1. Mary Elitch: "The Lady of the Gardens"

In the late 19th century, there was a young couple with a dream. He was a restauranteur, she was an usher and a hostess, but they wanted to be zookeepers.

John Elitch and his wife Mary moved to Colorado in 1880 to begin working at a friend’s restaurant in Denver. Over the next decade, John and Mary worked hard, saving up money and buying land in the rapidly growing state capital. Finally, in 1890 they opened the gate of Elitch’s Zoological Gardens for the very first time. It was the first zoo west of the Mississippi River—the nearest other zoo was the Lincoln Park Zoo, nine hundred miles away in Chicago!

Elitch Gardens closed for the season that autumn, and unfortunately John would not live to see it opened again. In March of 1891, he caught pneumonia while traveling along the West Coast and died suddenly, leaving everything to Mary—including their beloved garden.

Mary, however, refused to let their dream die with John. She returned to Denver alone, and opened the gates for the spring season. And every year, for the next two and a half decades, Mary was there to open the gates in John’s memory.

Mary was the first woman in world history to own a zoo, and she managed it herself from 1891 until 1916. During this time it became a famous fixture of Denver life (“Not to see Elitch’s is not to see Denver!,” as the tagline went for generations). What was originally a zoo quickly became an entertainment hub, with the addition of rides and, most famously, the Elitch Theatre.

Under Mary’s management, Elitch Gardens became the site of many, many firsts for Colorado. The first films shown in the state were exhibited in the theater in 1896, and the first rollercoaster in Colorado was built in the gardens in 1903.

Mary sold the zoo in 1916. She was independently wealthy—unusual for a woman at the time—and now twice a widow. She retired, but remained a public figure. She lived in the bungalow she and John had built on the park’s lands until she passed away in 1936.

"Not To See Elitch's Is Not To See Denver", written in a flower bed at the park c. 1890-1920.

#2. Mary Florence Lathrop: “I’m either a lawyer or I’m not!”

Mary Florence Lathrop was one of those people who knocked out a whole battery of firsts, one right after the other.

She began her professional life as a journalist, but quickly changed over to law. She attended the University of Denver Law School, where she graduated summa cum laude in 1896. Her score for the Colorado Bar would stand as a record, for both men and women, until 1941.

After graduating she became the first woman to open a legal practice in the state of Colorado. Many of her male colleagues refused to acknowledge her at first, but she soon rose in popularity and success. She became the first woman to try a case before the Colorado Supreme Court in 1898 (Clayton v. Hallett), a high-profile case involving a mountain man, an orphanage, and a sum of $2.5 million.

In 1901 she was invited to join the Colorado Bar Association, but she turned the invitation down for reasons unknown. She was invited again in 1913, this time unanimously. She accepted and became the organization’s first female member. In 1917 she scored another first when she became one of two women to simultaneously join the American Bar Association—the first time any women had been a member of that organization, of which she later became vice president!

Lathrop was a philanthropist and social figure as well as a lawyer. She often made anonymous donations to help struggling students, and during the Second World War she became known for entertaining soldiers at huge Thanksgiving and Christmas parties.

Mary Lathrop passed away in 1951, but she left behind a legacy that is still with us to this day. An award in her name is presented each year by the Colorado Women’s Bar Association to “outstanding female attorneys who have enriched the community through their legal and civic activities.”

#3. Helen Marie Black: “Elegant Dreadnought of the Denver Symphony”

Helen Black began her career with a bang. She was a journalist in Denver during the Roaring Twenties, and quickly made a name for herself with spectacular interviews of famous figures of the time. Aimee McPherson, Charles Lindbergh, Helen Keller, and Harry Houdini were all featured in her articles, and within five years of graduating journalism school she’d already risen to the rank of society editor for the Rocky Mountain News.

She was briefly hospitalized in 1926, and this seems to have altered her life course. She quit the newspaper and became a publicist, working for various companies around Denver. During this time she maintained her connections to high society, and became involved in many local organizations—including as the volunteer publicist for the Civic Symphony.

During the Great Depression, high society in Denver began to flounder. In particular, local musicians were struggling to find paying work even after unionizing. Through her work with the Civic Symphony, Helen Black took notice of this dilemma, and set about fixing it.

In 1934 she joined forces with two other notable Denver women—Jeanne Cramner and Lucille Wilkin—and together they founded the Denver Symphony Orchestra.

This was the first time an orchestra had been founded by women in the United States, and simultaneously Helen Black became the very first female symphony manager in the nation’s history. In fact, she was the only woman to hold that title in the country for nearly twenty years.

Helen Marie Black also helped refurbish the Central City Opera House (pictured here, 1934), where the Denver Symphony Orchestra often played.

Throughout her time with the orchestra, Helen Black remained a larger-than-life figure in Denver society. Ever the sensationalist, she became well known for her publicity stunts—such as releasing doves during the climax of a performance, which garnered the orchestra national attention. She was later called “a woman for all seasons” and “a wispy, gentle, elegant dreadnought” by those she worked with, and was known for her “wonderful manners and indomitable will.”

Helen Black was the orchestra’s manager for thirty years, during fourteen of which she went completely unpaid—she was a volunteer first and foremost. She was driven by her love of spectacle, art, and music, and only began receiving pay after fourteen years of hard work.

Even after her retirement in 1964, at the age of 68, she continued to do volunteer work around the city until she died more than twenty years later.

#4. Florence Sabin: “A New School of Anatomy”

Florence Sabin was born the daughter of a schoolteacher and a mining engineer in Central City, Colorado, and from adolescence had an interest in math and the sciences. As a young woman she taught high school mathematics in Denver, but this was only temporary. She needed the job to save up money for her true ambition: to gain a doctorate from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

When she enrolled in 1896, she was one of only fourteen female students in the school, but she refused to let this slow her down.

Sabin was quickly noticed for her perseverance and sharp observational skills, and was sponsored in two research projects that would become landmark developments in the world of medicine, including the first three-dimensional model of a human brainstem.

After graduation she remained at Johns Hopkins and quickly rose through the ranks—within two years she was granted an associate professorship. She was the first woman to teach at Johns Hopkins, and by 1917 she became the first woman to ever hold a full professorship at a medical college.

In 1925, she left the college to focus on research. Within the year, she was appointed the head of the Department of Cellular Studies at the Rockefeller Institute—the first time a woman had ever held a department head position at that organization. In the same year, she became the first woman to join the National Academy of Sciences, and was the only female member for more than twenty years.

During her time at the Rockefeller Institute, she helped with the development of important research into immunology (the study of how the body fights disease), and her work helped lay the foundation for the cure of tuberculosis and many other illnesses that had long plagued society.

She retired in 1938 and moved back to Colorado, but she wasn’t idle for long. Five years later, she was appointed to a state committee on public health. She later went on to say that she had been appointed because the governor had no interest in public health reform and believed an “old lady” would not be able to accomplish anything.

He was wrong. She fought ferociously for public health standards in Colorado, and the “Sabin Health Laws” are on the books to this day. Her reforms helped reduce rates of tuberculosis in Colorado cities and served as the model for laws in other states.

She retired again in 1951, approaching eighty years of age, but continued to fight for public health issues until she died two years later. To this day she is well-remembered across the nation for her research and tireless work.