Story

An Investigator, Minus the Badge

For thirty-one years, Dorothy Kemp Heller served Colorado Springs as its not-quite-a-policewoman social investigator.

The former home of Dorothy Kemp Heller sits on a hillside north of downtown Colorado Springs, in the heart of a nature preserve belonging to the University of Colorado–Colorado Springs. On summer days, the pristine white adobe house reflects the sun as it drifts westward, igniting the sky above Pikes Peak with color. It’s quiet here, about a half mile from the main thoroughfare of Nevada Avenue where the sounds of traffic are muffled by the surrounding acres of cascading prairie.

Nearly ninety years ago, when the house her husband Larry built was still new, this place—nicknamed Yawn Valley—became Heller’s retreat from her daily work as a Colorado Springs social investigator. Her job brought her up close to women and children who were in trouble, along with perpetrators of domestic violence. It was a tough job, but she bookended most days by enjoying time in her garden beds or with her horses.

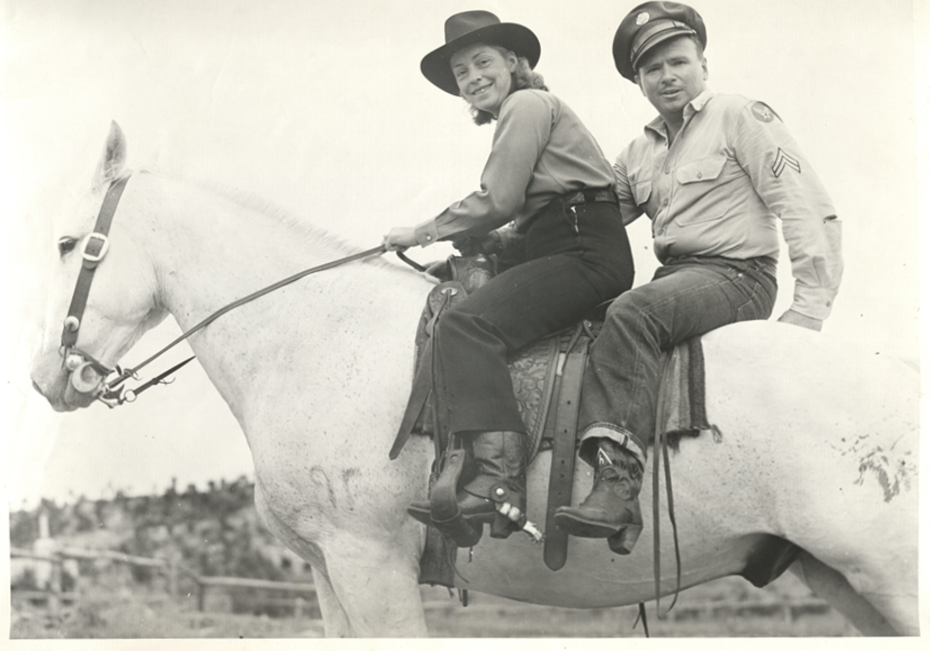

Dorothy Kemp Heller with her husband, Larry. The couple kept horses on their 33-acre property in Colorado Springs.

Born to Daniel Walter Kemp and Sarah Rosalie Kemp on October 6, 1905 in Indianapolis, Dorothy Kemp grew up in Anderson, Indiana. Vice president of her class, she graduated high school there in 1923 and enrolled at Butler University in Indianapolis. At eighteen, according to a 1965 article from the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, “she was the first playground director ever appointed in Anderson,” a job she returned to each summer while she was in college. She completed her bachelor’s in sociology from Butler in 1927 and returned to Anderson to work for the YWCA with teenage girls.

A year into her role, Dorothy won a scholarship for a three-month training through the National YWCA Training School at Cornell University in New York City. Another two years later, in 1930, she moved to Colorado Springs to work with the local YWCA’s teenage girls club as Girl Reserve Secretary. Then, in 1934, she took the city’s social service examination and on July 24 of that year, she was appointed as the city’s fifth-ever social investigator.

According to Dwight Haverkorn, former Colorado Springs police officer and department historian, Colorado Springs had established the social investigator role in 1914 in answer to calls for a woman police officer. But rather than reporting to the chief of police, Dorothy and her predecessors worked directly under the city manager (and later the mayor). They couldn’t make arrests or carry a gun, and until 1962 they were paid from the city’s budget rather than that of the police department. Dorothy’s starting salary in 1934 was $100 a month, a pretty good living for the times.

At that point, Colorado Springs was no longer in a mining boom, and the Depression was taking hold nationwide. The destination for artists, wealthy patrons, and tuberculosis patients had grown to about 30,000 residents, and the loss of employment and financial resources led to related crimes, like shoplifting and petty thefts, Dorothy told the Rocky Mountain News in 1965. Dorothy’s responsibilities included any case involving women or children. These ranged from juvenile delinquency (often runaways), child abuse and neglect, sexual crimes, alcoholism, and domestic violence.

Two years into the job, on May 29, 1936, Dorothy married Lawrence Heller, a local artist. When the United States entered World War II, Larry was assigned as a military artist for the Army Air Corps and stationed in Texas, while Dorothy stayed in Colorado, raising beef cattle at Yawn Valley to address the meat shortage and continuing her work with the city.

Dorothy served Colorado Springs as social investigator from 1934 to 1965, the longest anyone held that title.

The war brought an increased level of crime to town. So-called “victory girls,” young women and teenage girls who followed Army camps and provided varying levels of company and sexual favors to soldiers, arrived in droves. While some victory girls were married to soldiers, many were unwed, and military officials and local governments frowned on their presence. Prior to the war, Dorothy hardly ever dealt with women being locked up in the El Paso County jail, apart from traffic violations or drunkenness. But according to Dorothy’s estimates in a 1948 Gazette article, the war brought about 500 victory girls to the jail each year—twenty-five to thirty women daily—requiring the jail to stock up on more bedding, dishes, and food.

“I don’t know what we would have done without her,” Chief of Police I.B. Bruce told the Gazette. “She interviewed each girl, found out where each was from and why she was here. In most cases the girls had no money. Mrs. Heller contacted the police department, the sheriff’s office and welfare and health agencies, and the unfortunate ones were given transportation home and money to buy their meals on the way.”

Over her thirty-one years on the job, Dorothy was repeatedly honored by her colleagues in the press for her ability to gain the confidence of women and children: “She knows kids, and understands how to deal with them. She is definitely not the hard-boiled, police-woman type,” Chief Bruce told the Gazette in a 1950 article, where Dorothy was named “Woman of the Week.” In the same article, Chief of Detectives Earl Boatright described her as “eighteen carat [gold]” and said, “She is sincerely interested in humanity. She knows how to talk to people…[is] completely sincere and a fine investigator.”

In the same article, Dorothy reported that after the war, she witnessed more alcoholism among women, more mental illness, and more cases of neglected children. She advocated for improved mental health resources, sharing the story of a boy who repeatedly stole bikes—even after he was given a new bike to prevent future thefts. “Obviously he needed other treatment,” she said.

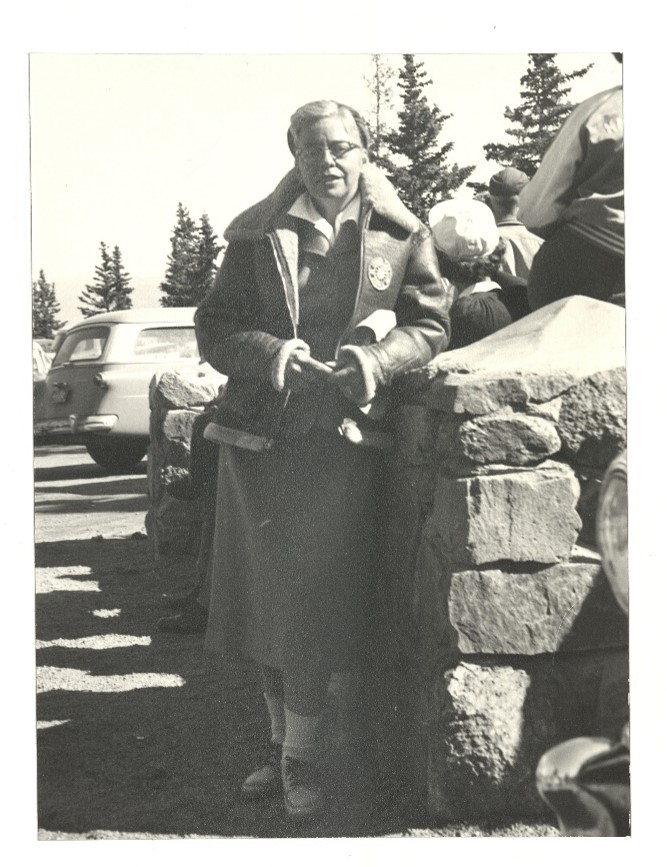

Dorothy’s work didn’t end with her retirement in 1965. She shared her expertise in articles for Law & Order magazine.

In the 1960s, toward the end of her career, Dorothy’s role was moved to the police department and she worked with Police Chief Cecil J. McKissick to establish the department’s juvenile bureau, though she was still classified as a civilian employee. Her work was noteworthy enough that her hometown paper, the Anderson Herald Bulletin, picked up an article from the Denver Post describing the unofficial counseling service she offered to young girls with the aim of preventing delinquency.

Dorothy retired as a social investigator in 1965 without ever bearing the title of “officer.” The following year, she published an article about child molesters in Law & Order magazine, where she pointed out that molesters were usually employed and often close relatives of victims, a shocking claim at the time.

While her social investigation days were over, the lessons and experiences she gained from that time guided her continual community involvement. She lived another thirty-four years and died January 22, 1999, in the house her husband built on the spacious property she gifted to the University.