WPA Privy (1935-1943)

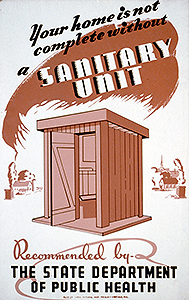

While the Work Projects Administration is known for a wide variety of public architecture, one of their more prolific programs was a health-related campaign to provide sanitary privies, particularly in rural areas. This program ultimately resulted in 2.3 million WPA-built privies in the nation; nearly 32,000 of those were in Colorado. While other New Deal programs supplied some 600,000 sanitary privies across the nation, the WPA concrete vault sanitary privies provided a substantial change in sanitation infrastructure for rural American communities, creating a significant increase in the quality of public health. These simple buildings are readily recognizable due to their standardized plans.

In the early twentieth century, scientific advances made it possible for health professionals to identify the ways in which poor sanitation led to various illnesses. In particular, the sanitary disposal of human waste reduced the incidence of “typhoid fever, diarrhea, dysentery, hookworm, and other enteric diseases.”1 The Rockefeller Foundation made public health infrastructure one of its primary initiatives; its Rockefeller Sanitary Commission initiated a groundbreaking hookworm study (1909-1915) and assisted the U.S. Public Health Service in implementing sewer systems and septic tanks in urban areas, and sanitary privies in rural areas. The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission determined that earthen privy pits needed to be at least six feet in depth to prevent hookworms from making their way to the surface. Earthen pits did not necessarily prevent the spread of other parasites and germs, but pit privies with deeper holes did marginally improve health conditions. The U.S. Public Health Service began to partner with state health departments to expand public education and infrastructure for sanitation systems as a result. In 1933, the U.S. Public Health Service published plans for various types of sanitary privies, including a sanitary privy that incorporated a poured concrete vault.

State health departments had distributed plans for sanitary privies during World War I and in the 1920s, but the Great Depression made construction of sanitary vault privies a financial impossibility for most Americans, particularly in rural areas. When the Civil Works Administration (CWA) formed in December 1933, the U.S. Public Health Service partnered with that agency to distribute sanitary vault privies using their recently published designs. The U.S. Public Health Service provided technical oversight of projects, CWA provided the labor, and property owners provided the raw materials. The CWA privies implemented several of the 1933 U.S. Public Health Service privy designs, and the agencies quickly learned that the sanitary privy designs with wood vaults and floors were difficult to keep clean and quickly deteriorated, making the poured concrete versions the preferable model.

During its few months of operation, the CWA’s style of privy construction and distribution served as a demonstration project for successfully implementing sanitation infrastructure, which the Work Projects Administration (WPA) continued. While the U.S. Public Health Service concrete vault model had an oval pot in the privy, the WPA simplified this plan by making the pot square, making it easier for construction crews to create the form to mass produce the concrete vaults. From the exterior, CWA privies look nearly identical to WPA privies; but on the interior, the WPA privies all had a square pot set at a 45 degree angle. Another advancement of these types of privies was a lid on top of the pot and a separate ventilation shaft with screens to keep flies out.

In Colorado, the state health department organized WPA privy construction and distribution, with centralized production and a multi-county regional distribution. While nearly every county had a sanitation project, the WPA did not record specific locations for each privy they placed. These privies arrived at “individual homes, farms, school buildings, dairies, filling stations, tourist camps, and many public places.”2 The standardized design made it easier for the WPA to mass produce these concrete vault sanitary privies, which also makes them easier to identify today. Some of the venting systems differ, but typically the vent is formed by a square wood shaft in the form of a T, terminating in screened holes on the sides of the privy walls. The greatest variety in WPA privies is in their wall cladding, where sometimes the regional production facility opted for horizontal clapboard rather than the standard vertical boards. In the San Luis and Huerfano valleys, the WPA privies are the reverse of the standard plan, placing the entrance door on the left and the pot on the right. The combination of interior and exterior features helps to differentiate the WPA privy from other types of privies that are still extant on the landscape.

Common Elements:

Exterior

- 4’ x 5’ wood-frame building set on concrete foundation

- Overhanging shed roof with 6”-wide fascia board on all sides

- Front façade divided in half with door on one (typically right) side

- Wood wall-cladding style varies by region

- Braced-board door (usually)

Interior

- Poured concrete vault below ground

- Top of vault serves as building foundation, with integrated concrete pot and vent hole above ground

- Square concrete pot at 45 degree angle in back (typically left) corner of building

- Smaller square concrete vent hole behind pot

- Square wood shaft from vent hole, typically terminating in a T with screened vent holes on the back and left side of the building

1 E.S. Tisdale and C.H. Atkins, “The Sanitary Privy and Its Relation to Public Health,” American Journal of Public Health 33, no. 11 (1943):1319.

2 Deon Wolfenbarger, New Deal Resources on Colorado’s Eastern Plains, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Denver, CO: Colorado Historical Society, 2005), E65.

Additional Sources:

- Ronald S. Barlow, The Vanishing American Outhouse: Privy Plans, Photographs, Poems, and Folklore (New York: Viking Penguin, 2000).

- E.S. Tisdale and C.H. Atkins, “The Sanitary Privy and Its Relation to Public Health,” American Journal of Public Health 33, no. 11 (1943): 1319-1322.

- U.S. Public Health Service, “The Sanitary Privy,” Supplement No. 108 to the Public Health Reports (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933).

- Deon Wolfenbarger, New Deal Resources on Colorado’s Eastern Plains, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Denver, CO: Colorado Historical Society, 2005).

- Work Projects Administration Poster Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.