Story

“To Think, Talk and Work for Patriotism”

The National Service School at Loretto Heights

With the onset of World War I came opportunities for Coloradans to do their part. Women were increasingly active outside the domestic sphere, and National Service Schools offered an important outlet in a time of unprecedented female activism. One of those schools found a home at Denver's Loretto Heights Academy, a Catholic school run by the Sisters of Loretto.

With great military fanfare and speeches by such dignitaries as Governor Julius Caldeen Gunter, the opening ceremonies of the Fifth National Service School unfolded on the lawn of Denver’s Loretto Heights Academy on July 2, 1917.

Women learn knitting at the National Service School at Loretto Heights Academy in July 1917.

National Service Schools, first established in 1916, were quasi-military training camps for women operated by the Woman’s Section of the Navy League, the first nationwide women’s military preparedness organization in the United States. The sinking of the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania in 1915 led to an outcry for increased military preparedness, prompting Elisabeth Ellicott Poe, a Washington, D.C., journalist, and her sister, Vylla Poe Wilson, to form a Woman’s Section of the Navy League to help protect the country against invasion by foreign foes and promote patriotism among American women.

Within a month, the organization had drawn 8,000 members. Upon joining, they recited this pledge:

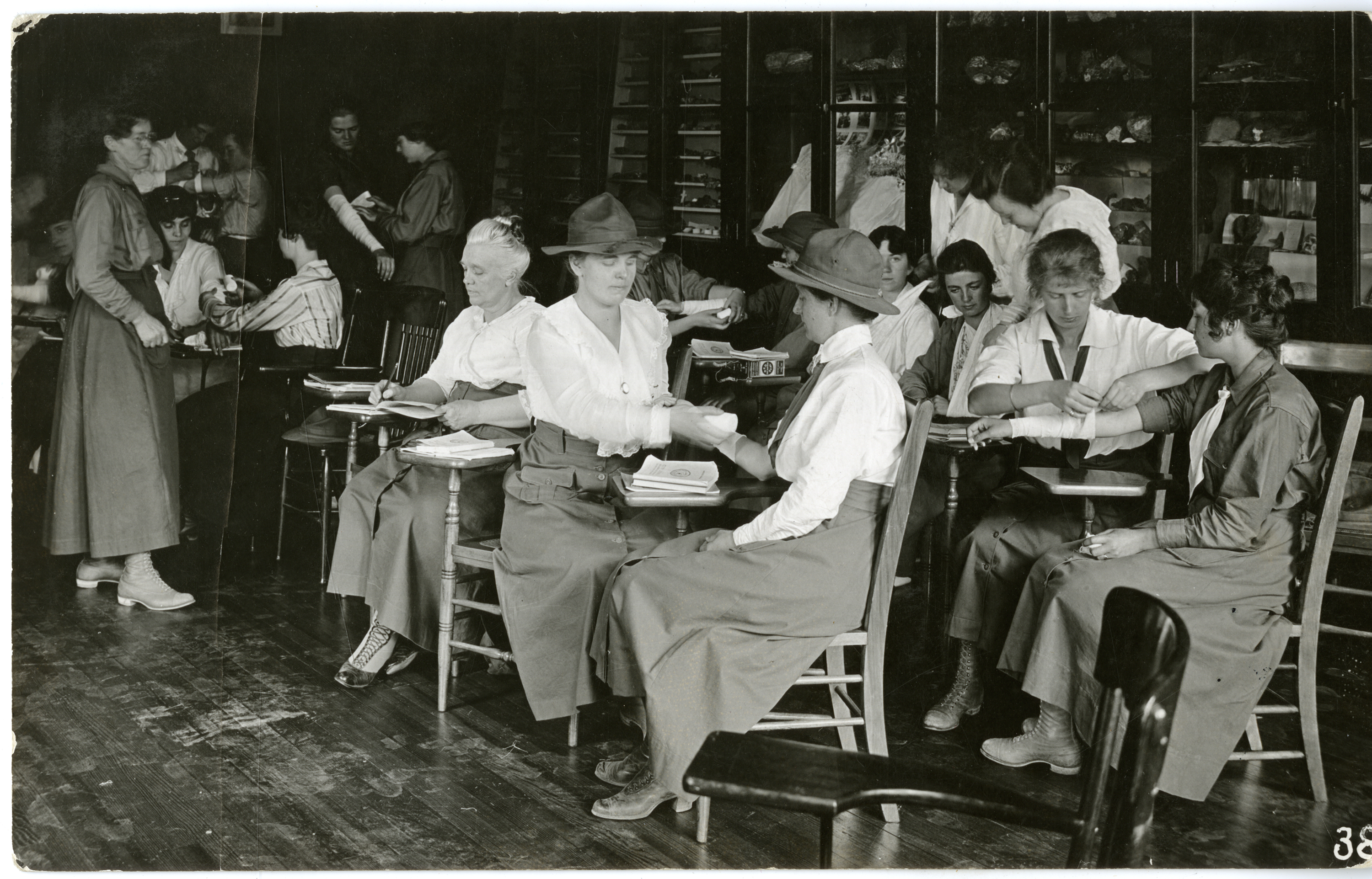

Women learn first aid at the National Service School at Loretto Heights Academy, July 1917.

I pledge myself to think, talk and work for patriotism, Americanism and sufficient National defenses to keep the horrors of war far from America’s homes and shores forever.

In these days of world strife and peril I will strive to do my share to awaken our nation and our lawmakers to the dangers of our present undefended condition so that we may continue to dwell in peace and prosperity and may not have to mourn states desolated by war within our own borders.

In so far as I am able, I will make my home a center of American ideals and patriotism, and endeavor to teach the children in my care to cherish and revere Our Country and its history, and to uphold its honor and fair repute in their generation.

The National Service School’s inaugural encampment took place in Chevy Chase, Maryland, in May 1916, with President Woodrow Wilson as the opening-day speaker and an audience that included Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and Secretary of War Newton Baker. National Service Schools at the Presidio in San Francisco, Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, soon followed. With a leadership group consisting primarily of the wives and relatives of military men, the camps appealed to women who did not strongly identify with the antiwar movement and wished to contribute to the war effort. Attendees were predominantly white middle- and upper-class women, typically from prominent families who could afford the camp fee and uniform costs. The typical working-class family could not afford to send a daughter to camp, nor could most independent single women afford to leave their jobs to attend a two- to four-week session. Day students were accepted at most camps but typically were segregated from the residential attendees and given fewer opportunities.

National Service School camps offered a standardized training program that emphasized discipline and obedience and was, according to the April 1918 Army and Navy Register, “just military enough to turn out, at the end of three weeks’ training, a body of women physically and mentally alert and ready for the service for which they have trained.”

Denver’s Sisters of Loretto generously opened the campus of their private Catholic school for girls to the National Service School for its fifth encampment during the 1917 summer break. Thirty-five white-walled canvas tents went up on the grounds to house attendees, instructors, and camp offices. The commanding Army officer at Fort Logan, General Robert Getty, detailed a bugler and two sergeants to provide instruction in military calisthenics and drilling, and over the next three weeks more than 100 women received intensive training in skills deemed useful to the war effort.

Attendees woke at 6:30 a.m., donning soldierly khaki uniforms, broad-brimmed hats, and drill boots before marching to mess at 7:30. Their typical training day included military drills, Red Cross instruction in caring for the wounded, and classes in military communications, wireless telegraphy, typing, stenography, knitting and other skills.

Officers pose at the National Service School at Loretto Heights Academy in July 1917.

Many of the women who attended the Fifth National Service School at Loretto Heights Academy become valuable assets in the war effort. Some served in the Red Cross or joined other national service organizations. One French-speaking attendee responded to the government’s call for female recruits to serve as telegraph and telephone operators overseas. Others traveled to assist Colorado fruit growers in picking and conserving the 1917 harvest, while still others volunteered to teach semiweekly lessons in military calisthenics and drilling in their communities.

At a time when women were increasingly active outside the domestic sphere but not yet in the workforce in large numbers, National Service Schools provided yet another important outlet for female activist energy. As historian Barbara Steinson writes, the women’s organizations related to pacifism, military preparedness, and war relief that emerged in the United States after the onset of World War I “coincided with the increased momentum of the suffrage campaign and mark the years from 1914 to 1919 as a period of unprecedented female activism.”

Loretto Heights Academy was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. An amendment to the original nomination is currently being prepared to recognize not only the exceptional quality of the campus’s architecture and the importance of Loretto Heights and the Catholic academy movement in the education of Colorado’s young women, but also the outstanding role the campus played in women’s history. The amendment is part of a larger project involving the rehabilitation of historic Pancratia Hall, in the oldest portion of the campus, with the assistance of Federal Preservation Tax Credits.

Properties listed in the National or State Register may be eligible for investment tax credits for approved rehabilitation and to compete for State Historical Fund grants.

More from The Colorado Magazine

The Women of the WAC Woman Soldiers at Fitzsimons General Hospital

Creede and World War I—A Knitter’s Tale It was the summer of 2000 and eleven-year-old Lizzie, a beginning knitter, hoped she’d found a mentor—her ninety-four-year-old grandmother, Mary Elting Folsom. Lizzie’s question took Mary back to 1917, several months after the US entered World War I.

Nine of Our Favorite New Additions to the Collection Amid a global pandemic, economic struggles, protests for racial justice, unprecedented wildfires, and political burnout, History Colorado collected through it all. Here are some of our favorite acquisitions from 2020.