Story

Creede and World War I—A Knitter’s Tale

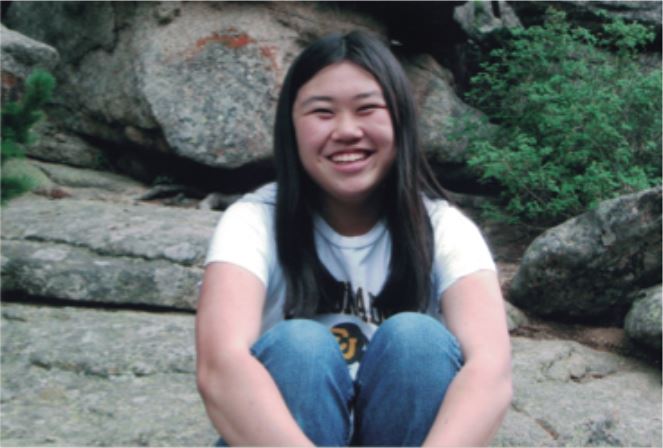

“Grandma, do you know how to knit?”

It was the summer of 2000 and eleven-year-old Lizzie, a beginning knitter, hoped she’d found a mentor—her ninety-four-year-old grandmother, Mary Elting Folsom. Lizzie’s question took Mary back to 1917, several months after the US entered World War I.

Yes, Lizzie, I do know how to knit. I learned during the summer of 1917, when I was eleven. Surprisingly, my teacher was a British army recruiter who had come to my home town of Creede, Colorado.

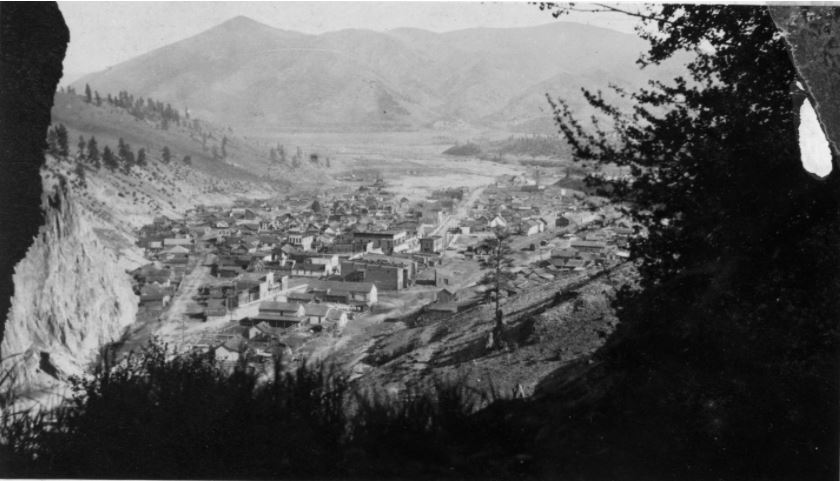

Located high in the San Juan mountains of southern Colorado, Creede was a silver mining town when Mary was born in 1906. Silver had been discovered there in 1889, just before the US Congress passed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. This legislation required the US Treasury to make substantial monthly purchases of silver, for which it issued special silver-backed paper currency. The price of the metal quickly shot up, and in a matter of months Creede became one of North America’s wildest mining camps. The silver craze attracted more than ten thousand prospectors, miners, and adventurers, who took up residence in tent cities that ringed the town.

Legendary figures of the Wild West were among the town’s new inhabitants. Bat Masterson turned up, not as a lawman but as a saloon keeper. Bob Ford, killer of Jesse James in Missouri in 1882, also came, only to be gunned down himself in his own saloon in 1892. Swindlers and gunfighters, gambling halls and brothels—that was Creede in its heyday.

Then, in 1893, an economic panic hit the country and people began exchanging their new silver-backed paper currency for gold coins. Fearing a run on its gold reserves, the US Treasury stopped buying silver altogether. The price of the metal fell dramatically, ending Creede’s three year run as a silver boomtown. Work continued at the largest mines, but the population of the town soon fell to about a thousand. Still, Creede’s early rowdiness remained a part of town life through the time of the First World War.

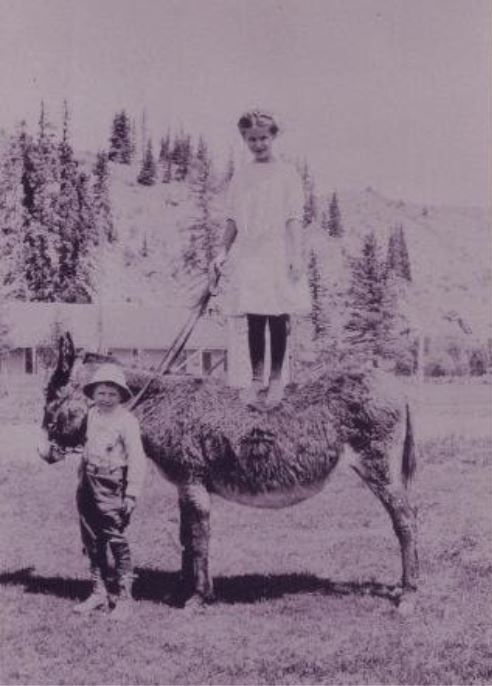

In the midst of Creede’s roughness, Mary grew up in a respectable middle-class family. Her father was a storekeeper who sold hay and grain for the town’s horses and mules. Her mother was a former schoolteacher who gave Mary a proper upbringing. When Mary asked why the women standing in front of a house down the street were wearing kimonos, her mother answered sharply, “You’re too young to know.” Years later she realized that the establishment had been a brothel. In summer the family retreated from rough-and-tumble Creede to Antler’s Park, a former dude ranch they owned west of town.

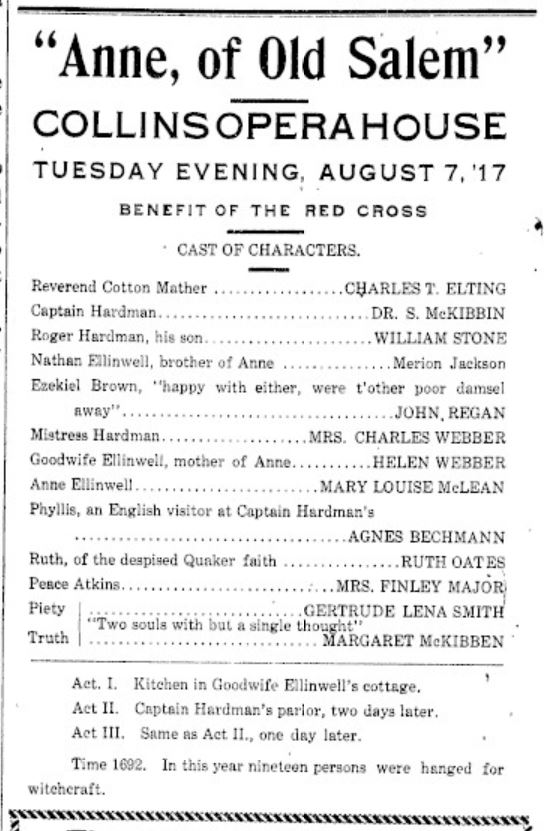

Mary’s father, Charles Elting, had come to Creede as a young man—his doctor had recommended a move from New York State to the western mountains as a treatment for his tuberculosis. He arrived in Creede during the boom years and for a while stayed in a tent next to Bob Ford’s. Twenty-five years later, in 1917, he had become a prominent citizen. That spring he was appointed Mineral County’s representative to the Governor’s War Council in Denver. Then, in August, he played Cotton Mather in the town’s production of Anne of Old Salem, a fundraiser for the Red Cross.

While we were at Antler’s Park during the summer of 1917, the English recruiter stayed with us in one of the cabins on the ranch. Recently disabled by a war injury, he came to my school and talked about what life was like for soldiers. The stories were horrifying. Everyone squirmed when he gave a graphic description of “cooties”—the lice that plagued soldiers night and day.

That summer the war was on everyone’s mind. News of the conflict filled the pages of The Creede Candle, the town’s four-page weekly newspaper. The Candle exhorted young men to volunteer for the army, and urged everyone else to get to work: “‘No work, no eat’ is the slogan. The war leaves no room for slackers.” Slackers took a beating all summer long.

A Candle feature called “Local Siftings” was Creede’s public message board. Townspeople could post announcements or proclamations on almost any topic. Rental rooms with electric lights were advertised. Special events were noted: A Tom Thumb wedding, where small children dressed up as bride and groom and acted out a wedding ceremony, was a great hit. And there were expressions of outrage. Colorado had become a dry state in 1916, and an irate prohibitionist railed against unchecked drinking in town: “This constant flow of booze has disgusted many of our better citizens and should it continue an awful roar will be heard.”

The Siftings reported all sorts of comings and goings: Ada Skinner was in town between trains, and John Glendinning stopped by while bringing his sheep to higher pasture. Especially prominent were reports about anyone going anywhere by automobile: Doctor J.A. Biles motored up from Del Norte to look in on Mrs. Broadhead; a fellow named Duncan was driving around in a new Buick he had bought from sales agent Lulu Voss; and Charles T. Elting, Mary’s father, had been a business visitor in Monte Vista the previous Saturday, making the trip in his automobile.

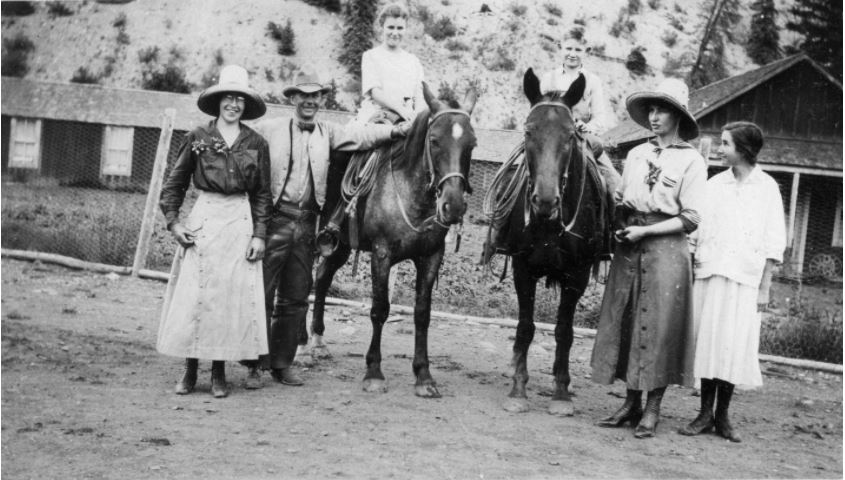

Mary’s parents, with their first car—a 1917 Dodge—that Mary learned to drive with, and that Charles later pushed into a ravine.

Mary’s father had just bought his car in Denver, and with no instructions and no training had managed to drive the 250 miles back to Creede without mishap. The next day he taught eleven-year-old Mary to drive—licenses weren’t required in Colorado until the 1930s. Some time later his car stalled along a high mountain road. Enraged when he couldn’t get it started, he tipped the vehicle over, flipping it into the ravine below. Apparently his sometimes-volcanic temper was well-known. Mary was reminded of this during a visit to Creede in 1994, when she encountered an old man who looked dimly familiar. Evidently he thought the same about her, leading to this exchange:

Old-timer: “Are you from around here?”

Mary: “Why yes—I'm Charlie Elting’s daughter.”

Old-timer: “That old sonofabitch?”

While The Candle and its Siftings column had much to say about many aspects of town life, it never mentions the British army recruiter.

The recruiter came to Creede because he was looking for Cornish miners—miners from the Cornwall region of England—who had not taken American citizenship. His mission was to persuade them to return to England and fight in the war.

Because mine management would not have wanted any of Creede’s skilled miners lured away to join the British war effort, the recruiter wisely did not publicize his visit.

Much of World War I took place underground, in trenches and tunnels designed, dug out, framed, and shored up by miners in the military. When troop advances stalled in late 1914, a meandering front line, extending from the North Sea to Switzerland, separated the German army on the east from the British and French armies on the west. Soldiers on both sides dug deep trenches along the front line so that combatants could stay below the enemy’s line of fire. A narrow strip—“no-man’s land”—separated the two sides. Side trenches linked the trenches along the front with underground living spaces, first-aid posts, and command centers.

Both sides also dug attack tunnels. Long and deep, these tunnels extended beneath enemy lines. The British enlarged the far ends of their tunnels and packed them with explosives, to be detonated underground just as their soldiers began a surface attack. By the spring of 1917 the British had built a series of attack tunnels under German lines near the town of Messines, in Belgium. Altogether these underground bomb chambers held almost five hundred tons of explosives. When they were detonated on June 7, the enormous blast killed ten thousand German soldiers and was heard in London one hundred fifty miles away. At the time the blast created what was thought to be the largest artificial sound ever produced.

Wartime tunneling efforts were huge—as many as forty thousand men worked on trenches and tunnels for Britain. Because trench and tunnel work was miners’ work, the British required a steady stream of fresh miners for its military efforts underground. While Cornish miners were highly skilled and especially sought after, they were in short supply by the time of the First World War.

In the first half of the nineteenth century Cornwall dominated world tin mining. But when much cheaper ores from overseas became available in the 1870s, most tin mines in Cornwall closed. The region’s copper mines suffered a similar fate. In the last decades of the nineteenth century several hundred thousand people—mostly unemployed miners—left Cornwall for mining regions around the world, including Colorado.

During World War I the mining of coal and metals were considered so essential for heating homes, powering factories, and manufacturing armaments that when conscription began in 1916, miners were generally exempted from military service. At the same time, Britain was desperate for soldiers with mining skills. Cornwall’s miners were offered double wages if they agreed to enlist, and as manpower shortages continued, Britain searched overseas for expatriate Cornish miners who might be persuaded to return and join the fight. Mary’s knitting teacher was part of that overseas mission.

Creede’s immigrant miners who had not taken American citizenship were put in an awkward position once the US entered the war, and a Candle editorial on June 16 underscored their predicament: “Alien citizens of all allied nations in this country should not be allowed to remain in safety here while our own boys are sent abroad to fight. Put ’em in the army or send ’em home.”

The grim physical realities of soldiering during World War I made joining the British army a difficult choice for Cornish expatriates. Soldiers endured unending bombardments in trenches that were filled with deep, oozing mud, and they were preyed upon by the cooties Mary’s schoolmates had heard about.

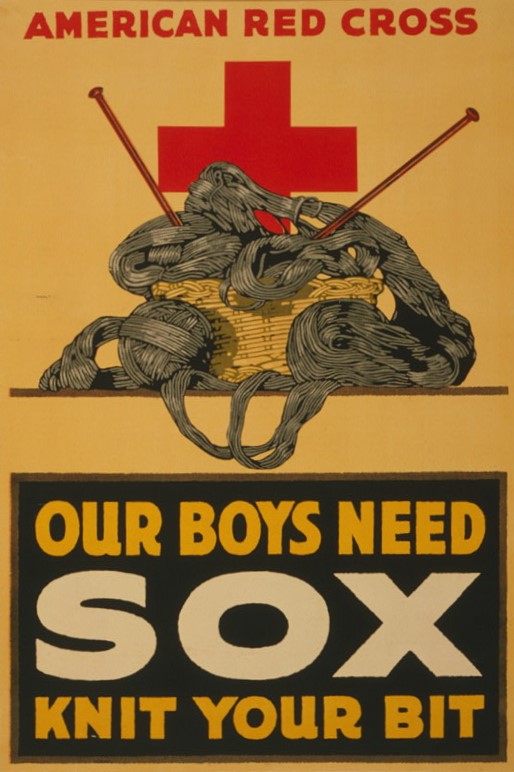

As protection against the ever-present muck, high boots were an essential part of every soldier’s outfit. Unfortunately, American soldiers were issued boots that leaked. This created a dire need for a second layer of protection: thick wool socks.

Shortly after he arrived at Antler’s, the Englishman asked me, “Little girl, do you know how to knit?” I admitted that I didn’t. He replied, “Well, by tomorrow you will.” He started me off with wash cloths. They were boring. So the next day he brought me wool and small needles for knitting socks. His stay at the ranch lasted long enough for him to keep me at the task until I could turn the heel and “toe-off” properly.

In the summer of 1917 the Red Cross called for a half a million pairs of socks to be knit by civilians for soldiers going off to war. Mary had been recruited to help with this huge project. The effort she joined brought together knitters from a broad cross-section of American society, and included firemen in Cincinnati, lifeguards in California, and women inmates at the Colorado State Hospital for the Insane in Pueblo. By the end of the war, participants had knit 370 million socks and other items for soldiers headed to Europe.

I jumped right in and started at it. This was how I could help our soldiers overseas.

While Mary was knitting socks, Lizzie’s grandfather, ten-year-old Franklin Folsom, was also determined to contribute to the war effort. He was spending the summer of 1917 with his grandmother in Pueblo while his father was serving with the army in Europe. Drawing on a fourth-grader’s sense of geography, he was expecting a German attack on Pueblo from across the nearby Arkansas River. To prepare for the attack he grabbed a shovel and began digging a trench behind his grandmother’s house. Sadly, he dug too close to the family’s five-hole outhouse, weakening its earthen supports. Later, when his rather large grandmother took a seat in the five-holer, the building collapsed, dropping her into the unpleasantness below. It took three men to pull her out.

Was the recruiter able to persuade any miners to return to England? I just don’t know.

It’s unlikely that many of Creede’s Cornish miners returned to England to enlist. Most had been away for decades, and tales of the unrelieved horror of trench warfare had surely reached Creede’s Cornish community. Of course, the recruiter would have pointed out that returning was a “now or never” decision—a British citizen was subject to Britain’s conscription laws, and so by refusing to return to fight, a miner would risk jail if he returned home at a later time. In fact, only a single Cornishman in America has been identified who returned to Britain during the war to join a tunneling company.

Mary thought about the war and her contribution.

All told I must have knit a hundred pairs of socks for our soldiers.

She paused, looked over at Lizzie, and added:

Then the Armistice came in 1918—and I haven’t knit since.

***

Mary died in 2005. A literary editor for ten years after college, by 1940 she had begun translating French children’s books into English. She soon realized she could write books for kids herself, and launched her career in 1943 with Soldiers, Sailors, Flyers, and Marines. Written to explain the Second World War to children, the book had an unexpected second use. The Navy ordered three thousand copies to help teach illiterate sailors to read.

During the next half-century she wrote almost ninety books, mostly for children, many co-authored with her husband, Franklin. She created a “First Book of” series that began with The First Book of Boats, and went on to trains, trucks, automobiles, and nurses. In her “Answer Book” series, she gave interesting answers to questions about science, geography, computers, and the human body. Along the way she also wrote about dinosaurs, volcanoes, archaeology, robots, and the history of corn. Her 1980 alphabet book Q is for Duck, written with her son, Michael Folsom, is still in print.

Mary had other interests. She was in on the founding of the Council on Interracial Books in 1965. A longtime member of the Jane Addams Children’s Book Awards Committee, she read hundreds of books every year in order to make recommendations for awards. Late in life she edited The Skeptical Inquirer, a periodical dedicated to debunking non-scientific claims about the paranormal and the supernatural.

An intrepid world traveler, Mary, with Franklin, took an eighty-day bus tour from London to Kathmandu. Afterwards they flew to Sri Lanka, where they did research for a magazine article on Buddhist eye banks for the blind. In her seventies she backpacked across the Grand Canyon, and in her eighties she visited Lhasa, Tibet, as part of a Boulder, Colorado, sister-city delegation. On a ninetieth birthday trip to Rome in 1996, Mary observed that the city had “changed a lot” since her last visit—in 1930 during the Mussolini era.

With almost one hundred years of material to work with, Mary was a great storyteller.

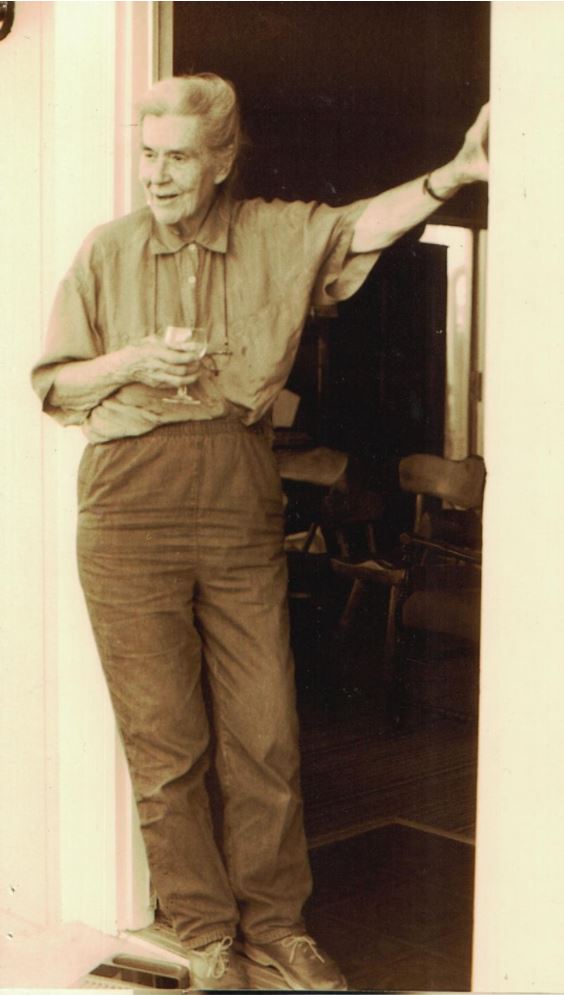

Sitting at the kitchen table, in her late nineties, glass of sherry in hand, she talked about how Creede coped with the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic (several of her schoolmates died); she recalled sorority life at the University of Colorado in the 1920s (sorority members mailed their dirty clothes home to be laundered); and she told stories about working for publishing houses in New York in the 1930s:

Let me tell you about the easiest job I ever had.

Mary let that sink in while she sipped her sherry.

One morning in 1936, when I was working as an editor, my boss came by and put a kid’s book manuscript on my desk. ‘Let me know after lunch if you think we should publish it,’ he said. I knew in a minute that we had a winner—the book was the children’s classic Ferdinand the Bull.

***

Franklin Folsom, Rhodes Scholar and author of eighty books for children and adults, died in 1995. Folsom Field—the football stadium at the University of Colorado, Boulder—is named for his father, football coach and law professor Fred G. Folsom.

***

Elizabeth Folsom Moll—Lizzie—is a city planner in Seattle.

***

For further reading

Anika Burgess. “The Wool Brigades of World War I,” Atlas Obscura, July, 2017

The Creede Candle, from the Colorado Online Historical Newspapers Site

Richard C. Huston. A Silver Camp Called Creede, Western Reflections Press, 2009

Nolie Mumey. Creede: The History of a Silver Mining Town, Artcraft Press, 1949

Joyce Nakamura and Gerard J. Senick, editors, Something About the Author Autobiography Series, Volume 20, “Mary Elting,” pp. 165-181

More from The Colorado Magazine

Bringing Back Blinky Museum Collecting in the Time of COVID-19

The Women of the WAC Woman Soldiers at Fitzsimons General Hospital

Immigration to Colorado: Myth and Reality For most of its history, America has been a haven for those seeking a better life and a refuge for those fleeing for their lives. Indeed, since its inception, America has been an inspiration to others, a place where the downtrodden could find hope. Among the proponents of immigration was President John F. Kennedy, who laid out his inclusionary vision of America in his 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants.