Story

Race, Privilege, and Landscape in Colorado History

As we look forward to Colorado Day on August 1, we asked each member of the State Historian’s Council to reflect on what “our beloved Colorado” means to them. Here, Jared Orsi reflects on who we mean - and who we exclude - when we say “our.”

One-hundred-twenty-seven years ago last week, Katharine Lee Bates penned a famous poem. Her verse underscores the privilege that many—not all—Coloradans have historically enjoyed by being able to access the state’s magnificent lands.

The Massachusetts English professor spent that summer teaching at Colorado College. One day, she and some friends made the arduous climb to the summit of Pikes Peak. The view took her breath away. Inspired, she wrote the lines Americans still joyfully sing today.

Oh beautiful for halcyon skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties above the enameled plain!

America! America!

Without a doubt, Colorado is beloved. Its spectacular scenery provided the basis for a hymn that links Americans’ patriotism to its landscape, starting atop Pikes Peak.

But on Colorado Day 2020, the nation is shredded by racial injustice and political division.

Like many Coloradans, I have favorite places that make the state beloved to me. But as I consider the theme of “our beloved Colorado,” I want to reflect on what the “our” means in that phrase.

Bates was white and consequently enjoyed privileges that most people of color at the time did not. Among these were leisure time, freedom of movement, a job that provided a little disposable income and did not involve physical toil, and the security of knowing her basic needs—food, shelter, and safety—would always be met.

She had the wealth needed to spend the summer quasi-vacationing in Colorado. She crossed the country in a comfortable railcar, unhindered by segregation and without fear of an arrest for vagrancy. Her general material security made a day roughing it on the slopes of Pikes Peak feel like sport. Thus, she faced few barriers to accessing the public good of outdoor recreation, indeed exhilarating in it.

For African Americans, in contrast, the 1890s saw dramatic rises in Jim Crow segregation, vagrancy laws, lynching, and poverty. A Black sharecropper from Mississippi, a dock worker in Baltimore, or a domestic servant in Boston should have been so lucky as to take time off work to engage in a grueling climb and call it beautiful.

The number of people excluded from “our” in Colorado history is large, too long for an article like this one. But here’s a start.

For one, there’s Amache, the Southern Cheyenne woman imprisoned in her home for two days in 1864 by the First Colorado Cavalry to prevent her from warning her kinspeople about the impending Sand Creek Massacre, where her father was killed. Her name was later applied to the World War II Japanese American confinement site near Granada, thus associating her with two moments when Colorado fell tragically short of beloved.

Amache Ochinee Prowers was a mediator between Colorado territorial settlers, Mexicans, and Native Americans during the 1860s and 1870s.

In the 1870s the cry went out, “the Utes must go!” In 1914, a multiethnic group of at least nineteen striking coal miners, many of them immigrants, and their unarmed wives and children, died in the Ludlow Massacre. In 1936, in a calculated political stunt, Democratic Governor “Big Ed” Johnson closed the state’s southern border for ten days to New Mexican “alien” laborers. In August 2019, Aurora police murdered an unarmed black man, Elijah McClain, walking home after buying iced tea.

And what would Bates, who lived in a committed relationship for twenty-five years with her Wellesley colleague Katharine Coman, have thought of Amendment 2? Would she even have written that America is beautiful had she visited Colorado in 1992, the year the state voted to withhold American freedoms from gays, lesbians, and bisexuals?

Colorado history has not treated such people in a beloved manner. I want to name them on Colorado Day to avoid mistaking the “our” in “our beloved Colorado” for being a universal “we.”

It’s a decidedly particular “we,” a group systematically and historically skewed in favor of people with paler skin, greater wealth, conventional sexual and gender identities, and able bodies.

The superficial differences among Coloradans don’t justify the unequal access to what is beloved here. It is an injustice to mistake a particular “we” for a universal one.

Jicarilla Apache campers join the author and his CSU history field course students for an intercultural dinner at Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

But I don’t want only to name injustice. Colorado can be beloved only if there is a “we” who recognizes it as so. Bates’s America is beautiful because it is shared, a “brotherhood [and sisterhood!] from sea to shining sea.”

A broad and inclusive “we” amplifies the worth of Colorado’s landscape for everyone.

It is incumbent on people who face the fewest barriers to accessing beloved Colorado to take the initiative to break those barriers down and ensure that the “our” in “our beloved Colorado” truly is universal.

One piece of doing that is to recognize deeper human commonalities across superficial differences, something history can provide.

Beloved Colorado began 13,000 years ago. The Front Range witnessed concentrated traffic as one of the important segments of the path by which people first entered the interior of North America. Long-distance trade carried objects from every corner of the continent into the hands of early Coloradans. There was plenty of game, comparatively mild weather, and easy access along a short thirty- or forty-mile ascent into the mountains to the bountiful resources of several ecological zones.

Transportation corridor, strong economy, high-quality of life, and opportunity beckoning from the heights. The amenities of long ago still attract people today. Those for whom Colorado is beloved now are only the most recent in a chain of humanity which has loved the land for a very, very long time.

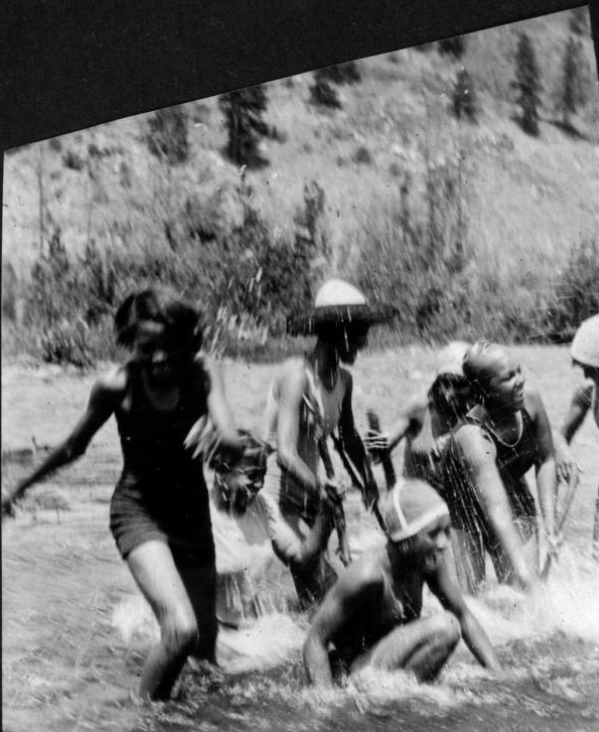

Campers frolic in river at Camp Nizhoni, 1929 or 1930

Or consider these young women at Camp Nizhoni, a YWCA camp at the African American mountain resort of Lincoln Hills, not far from Nederland. These swimmers and thousands of other visitors flocked to Lincoln Hills in pursuit of spacious skies and mountain majesties. African Americans craved mountain recreation at the very moment that it was rising in popularity among white people as well. More common humanity.

For me, the depth of time during which Colorado has been beloved is humbling. It connects me to many different kinds of people who have done exactly what I do now—value Colorado. I am not the first, the last, the best, or even at all notable. Just one of many. And I am not all that different from any of them.

Too often in history, privilege has been a prerequisite for finding Colorado beloved. These Coloradans teach us that finding something good in the state can sometimes come simply from encountering other Coloradans—from expecting division and instead finding compatibility.

A beloved spot in Colorado: the author atop Mt. Rosa, where Zebulon Pike gave up his ascent of Pikes Peak in 1806

This article also appeared in the "Colorado's Living History" feature of The Colorado Sun, an ongoing collaboration with History Colorado. The Colorado Sun is an independent, journalist-owned news site. Learn more at coloradosun.com/join.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Health, Recreation, Education, and Uplift: Lincoln Hills and Black Recreation in the Colorado Mountains When temperatures soared in cramped, noisy cities, Colorado’s higher elevations promised chilly nights and mild days spent fishing, camping, and hiking under shady pine trees. Unlike their white counterparts, however, African Americans could not head just anywhere in the mountains. Not far outside of Denver, Lincoln Hills, a vacation community developed for Black people, represented both an escape from the city and an escape from segregation.

The Post-NAGPRA Generation The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Thirty Years On

Colorado Is My Classroom More than a century ago, open-air classrooms had a moment in response to another pandemic. Then it was tuberculosis, another era-defining airborne pathogen that attacked the respiratory system. And the results were encouraging. Could fresh air be part of the solution to school in the time of coronavirus?