Story

Doing Our Part

Eleven Ways World War II Came to Colorado

Though many miles away from shipyards, aviation plants, and tank production facilities, Coloradans played an outsized role in the World War II conflict, and in bringing the troops back home.

Three-quarters of a century have passed since the most widespread and destructive war in history ended—a war that many historians have called the pivotal event of the twentieth century. That the conflict ended in victory for the Allied nations—the United States, France, the Soviet Union, Great Britain and its commonwealth partners, and others—has much to do with Colorado’s role in it.

While the state had no shipyards or tank or aviation production facilities, that didn’t mean Colorado’s contributions were insignificant. Far from it. Let’s take a look back and see what our state contributed to the war effort—and vice versa.

1. We Embraced the End of Isolationism

Ever since Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and then when Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, many in the United States had been viewing the growing conflict with alarm but also a reluctance to see the country get dragged into another foreign war. It was one thing to sell the tools of war (through the Lend-Lease Act of 1941) to Britain and the Soviet Union so that they could fend off the attacker, but sending American boys to fight was quite another.

That isolationist sentiment vanished in an instant on Sunday, December 7, 1941. The bombs that fell on Pearl Harbor sent shock waves across the country. Millions of young men (and many women, too), angered by the surprise attack, flocked to military recruiting offices, eager to serve their country. Colorado saw an outpouring of patriotic sentiment that has never been equaled; in December 1941 alone, more than 2,000 citizens swamped recruiters’ offices.

Women rig and inspect eight-man pyramidal tents manufactured to Army Quartermaster Corps specifications at the Schaeffer Tent & Awning Company in Englewood.

2. We Built the Arsenal of Democracy

On January 4, 1941, eleven months before the Pearl Harbor attack, the federal government, perhaps anticipating that war was inevitable, awarded a $122 million contract for the development of land, buildings, and equipment for the Denver Ordnance Plant—a “bullet factory” that the Remington Arms Company would operate. It would be built on the 7,000-acre Hayden Ranch in what would be known as Lakewood.

The contract was a godsend for Denver, which, like virtually everywhere across the Depression-ravaged country, was suffering from high unemployment rates. The Denver Ordnance Plant project created thousands of construction and factory jobs over the next five years.

On October 25, 1941, the bullet factory was dedicated at a ceremony, five and a half months ahead of schedule. Some 200 buildings were grouped according to function to lessen the explosion risks involved in ammunition production. Nearly 20,000 people—half of them women—worked in three shifts around the clock.

The primary product was the .30-caliber bullet—used in standard-issue American weapons like the M-1 Garand rifle, Browning automatic rifle, and M-30 Browning machine gun. Eventually the plant was turning out an astonishing 6.2 million rounds of ammunition per day—more than any other factory in the United States, and perhaps anywhere in the world. Workers later made fuses for 8-inch, 90mm, and 155mm artillery rounds. The plant was declared surplus in October 1945. Today, the complex of buildings, known as the Federal Center, sits at its original location at West Sixth Avenue and Kipling Street.

As young men were drafted or volunteered for military service, other massive changes began to sweep the state. Government contracts revived moribund businesses that had struggled to stay open during the Great Depression. The Schaeffer Tent and Awning Company, a small Denver manufacturer, received an order from the Army Quartermaster Corps for thousands of eight-man pyramidal canvas tents. Soon the plant was scrambling to find and train enough workers to turn out nearly 100 tents a day at its facility at 1421–1423 Larimer Street.

A worker stokes a furnace for the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company in Pueblo, around 1940.

The army needed vehicles, and Denver manufacturers answered the call. The Winter Weiss Company, at 620 Broadway in Denver, was a manufacturer of automotive items, including commercial auto and motorcycle bodies. It received an Army order to build thousands of platform stake trailers capable of carrying 7,000 pounds. Gates Rubber Company, farther south on Broadway, switched from making tires and fan belts for everyday use (virtually no new tires were available to the civilian market for the duration of the war) to making tires and fan belts for jeeps and other military vehicles. And the Coleman Motor Company of Littleton produced the Model G-55A 4x4 chassis with a 6-cylinder engine as the platform for a Model E crane made by Quick-Way Truck Shovel Company of Denver. Engineering units used the combined 4x4 truck-crane vehicle for bridging, construction, and other purposes.

Eight other Denver fabricating firms were shaping and welding hull parts to fulfill a $56 million contract for the U.S. Navy. They shipped the parts to Mare Island Navy Yard near San Francisco for assembly.

In addition to bullets and shells, tents and tires, the military needed weapons of great destructive power. In 1942, the U.S. Army acquired nearly 20,000 acres of land northeast of Denver and began construction of the $50 million (in 1942 dollars) Rocky Mountain Arsenal. This facility manufactured deadly chemical weapons such as mustard gas, Lewisite, chlorine gas, and incendiary (napalm) munitions because it was believed that the enemy was making the same. The controversial facility was deactivated in 1992 and, after extensive cleanup, turned into a wildlife refuge.

Pueblo also made a great contribution to the war effort. Colorado Fuel & Iron steelworks, then the state’s largest private employer, produced barbed wire, railroad rails, pig iron, iron and steel bars, and plates for use by heavy industry, as well as coal, limestone, and iron ore from its many mines across the state.

The Pueblo Ordnance Depot, 15 miles from the city, was built in 1942 to serve as an ammunition and material storage and shipping center; it employed thousands of defense workers during the war. Today, as the Pueblo Chemical Depot, its main function is to destroy hundreds of thousands of obsolete chemical weapons. A warehouse here was also once the repository for Third Reich propaganda war art before the collection, numbering about 300 pieces, was relocated in the 1980s to the U.S. Army Center for Military History in Washington, D.C.

The sudden availability of jobs brought in a tidal wave of new residents to Colorado. According to Colorado historian Tom Noel, in the decade between 1940 and 1950, Denver’s population grew almost 29 percent—from 322,412 to 415,786. The suburbs, too, exploded; Adams County’s population increased nearly 79 percent; Arapahoe County, 62 percent; Boulder County, 29 percent; and Jefferson County, 83 percent.

The Empire Zinc Mining Company in Gilman, Colorado, around 1930. Photo by George L. Beam and Otto Roach.

3. We Powered the War Effort

High in the mountains, the discovery of molybdenum, an element used to strengthen steel, brought the down-and-out silver- and gold-mining town of Leadville back from the brink of extinction. Steel was in great wartime demand and the ore from Leadville’s Climax Molybdenum mine became a highly prized commodity. In the 1940s, the mine’s annual production was more than $13 million. The mining boom, plus the presence of 15,000 young soldiers training for high-alpine warfare at Camp Hale just 10 miles away, brought an economic resurgence to the old town

Zinc, too, was an important metal. The Empire Zinc Company had established a mine at Gilman, south of Minturn, in the early 1900s. During the war, the mine was in full production. Empire Zinc built a company town on a spectacular ridge, which still stands along Highway 24, weathered and abandoned.

While mining companies continued to extract gold, silver, lead, and zinc from Colorado’s mountains, coal was an essential mineral, too—necessary for electrical power generation, factory furnaces, locomotives, and home heating. The Colorado coal-mining industry was primarily located in Las Animas and Huerfano Counties in an area known as the Southern Coal Fields. The major employer was Colorado Fuel & Iron.

In 1943, the scientists involved in the top-secret Manhattan Project contracted the Coors Porcelain Company of Golden because the company had the experience, expertise, and capacity to make large quantities of desperately needed ceramic insulators capable of handling the tremendous electrical loads produced by the calutrons used in the separation of uranium 235 and 238—materials needed to make atomic bombs.

That uranium: It came from Uravan, a mining town near Grand Junction.

The state’s agriculture sector also boomed with the heightened demands of wartime. In 1942, the federal government asked Colorado farmers to increase the production of their spring pig crop by 30 percent, eggs by 10 percent, and milk by 4 percent. The government asked cattlemen to increase the slaughter of cattle and calves by 18 percent and of sheep and lamb by 9 percent. And the feds requested a 13-percent increase in potato acreage along with a 6-percent increase in oats and 2 percent in barley and corn.

As a result, during the war Colorado had its highest agricultural output ever—much of which went to the armed forces, leaving little for civilians.

"Your Scrap Brought It Down" poster.

4. We Sacrificed for the Common Good

Though the state’s economic engines were on overdrive, Coloradans were not enjoying the benefits. Coloradans, like everyone else across America, were hit hard by rationing. The much-despised Office of Price Administration (OPA) imposed strict rationing on the American people for most of the war’s duration. As Time-Life noted, “The major sacrifice that was required of most people on the home front was involuntary—the unprecedented rationing of some 20 essential items by the federal government. . . . Canned foods, for example, were rationed because tin went into armaments and cans for soldiers’ C-rations, coffee because the ships that would ordinarily carry the coffee beans from South America had been diverted for military purposes, shoes because the Army alone needed some 15 million pairs of combat boots.” Rationing of items “from gasoline to tomato ketchup” kept supply chains active and inflation down.

Certain fabrics—such as silk and nylon—were in short supply because they were needed for parachutes and ropes. Skirts and dresses became shorter because cotton and wool were needed for military uniforms. Shoes were almost unattainable.

The Office of Price Administration issued every family a ration book and ration stamps that were required to buy items at the local grocery store. The OPA’s complex, ever-changing “point system” allotted a certain number of points to each food item—meats, butter, sugar, and processed foods—based on its availability.

It took 48 “blue points” a month to buy canned, bottled, or dried foods, and 64 “red points” to buy meat, fish, sugar, coffee, and dairy products each month—if the items were even available. Butter was so scarce that margarine, made from vegetable oils, became a substitute for the dairy product.

Because food shortages were real, many Colorado families turned backyards into “victory gardens” and built coops so they could raise chickens for fresh eggs and meat.

Strict quotas on gasoline purchases went into effect nationwide, beginning in the spring of 1942. Depending on one’s occupation, drivers with an “A” ration windshield sticker were limited to four gallons a week while those with “B” (issued primarily to business owners) and “C” (issued primarily to seventeen professions—physicians, nurses, dentists, clergy, farm workers, and construction or maintenance workers) stickers qualified for five gallons a week.

It goes without saying that black-market activities proliferated, both for gasoline and food.

In 1940, Colorado’s tourism industry was the state’s largest and most profitable enterprise, grossing about $100 million annually. But the onset of the war, with its gasoline rationing and other priorities, saw tourist travel in the West plummet by as much as a third. Further burdening tourism, the government imposed a nationwide speed limit of 35 miles per hour. Besides saving fuel required for military purposes, drivers had to cut down on their driving to save tires. Civilian tires were virtually unavailable during the war because rubber, needed for military vehicles, was in short supply.

No new cars were available for the duration, either; the major car manufacturers—Ford, General Motors, Dodge, Chrysler, Plymouth, Packard, Studebaker, Nash, Hudson, DeSoto, and Graham-Paige—completely ceased making cars for the civilian market and devoted their assembly lines to turning out military vehicles and aircraft.

Because of the scarcity of tires and fuel, many drivers simply put their cars up on blocks and waited for the hoped-for peace and return to normalcy.

To further give civilians the sense that “we’re all in this together,” the government encouraged nationwide scrap drives. In Colorado’s big cities and small towns, wherever there was a Boy Scout or Girl Scout troop, a 4-H Club, or a church youth group, young people could be seen pulling their Radio Flyer wagons from door to door, asking residents for their scrap. People gave up tin cans, iron, steel, and scrap aluminum, old tires, automobile bumpers, newspapers—anything that could be recycled and turned into military products. They even turned in kitchen fats so the glycerol/glycerine could be converted into explosives.

“Sacrificing” because of a lack of consumer goods paled in comparison to the personal sacrifices many families made. Virtually every household with a family member in the military displayed a “service flag” in a front window of their home or apartment. This was a small white flag with a red border and one or more blue stars in the center, each star representing one family member in military service. If a member was killed, the family could exchange the flag for one with a gold star, indicating the loss.

Colorado newspapers often carried stories about “local boys in uniform”—which, of course, included “girls” in uniform, too—and lists of casualties. Over 3,400 Coloradans died in the war that claimed over 405,000 American lives, and thousands more were wounded. Many, too, were listed as “missing in action”—a status that did nothing to ease the heartbreak.

5. We Provided Spaces for Bases

Facilities to train the millions of enlistees or draftees who had never fired a rifle or flown a plane were in great demand across the country, and Colorado saw its share of a nationwide military building boom.

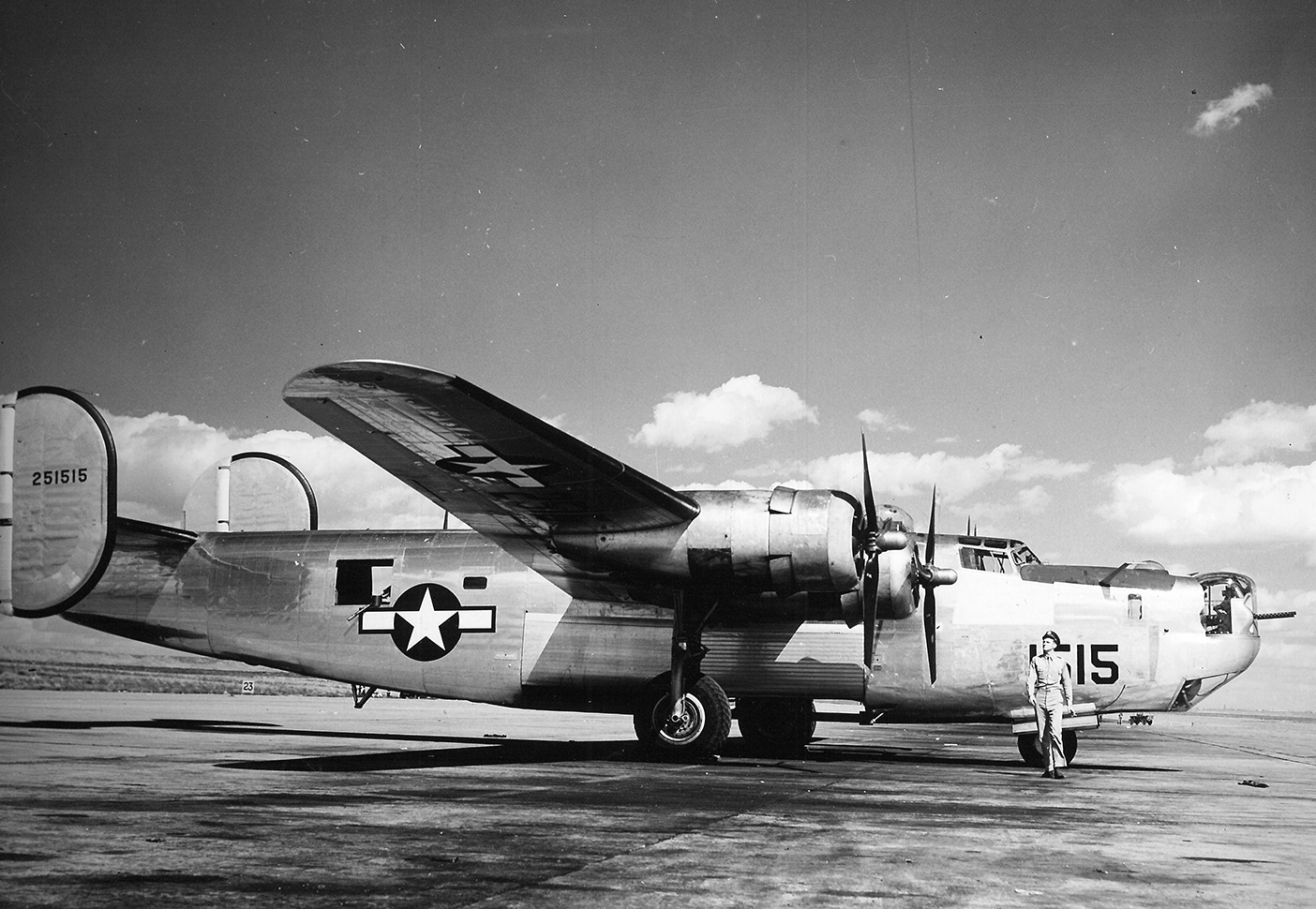

In Pueblo, the Army established an advanced school to train Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress” and Consolidated B-24 “Liberator” four-engine bomber crews. Eight different bombardment groups also trained there before being deployed overseas. Today the facility is the Pueblo Municipal Airport, which is also home to the Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum.

Colorado Springs also benefited from the building boom with several projects. South of the city, Camp Carson (named for the Army officer and fur trapper Christopher “Kit” Carson), sprawled across 60,000 mostly barren acres. On land bought by the city, civilian contractors completed the camp’s first building, the headquarters, on January 31, 1942—less than two months after the United States declared war on Japan and Germany. An army of 11,500 civilian workers quickly put up hundreds of other wooden buildings, and soon more than 35,000 new recruits and their cadre populated the post; more than 100,000 trained there during the war. Renamed Fort Carson in 1954, today it’s Colorado’s largest military establishment at 137,403 acres, or 214 square miles.

Nearby, the Army established the Colorado Springs Army Air Base in 1942; within a year its name had changed to Peterson Air Force Base—a name it retains to this day. Its name honors Lieutenant Edward Joseph Peterson, who died in a crash of his P-38 “Lightning” photo reconnaissance plane at the base in 1942.

A B-24 Liberator airplane at the Army Air Force Base and Ordnance Depot in Pueblo.

A smaller air base, named Ent Air Force Base after its first commander, Major General Uzal Girard Ent, was established in 1943 at the site of a closed sanatorium in the Knob Hill neighborhood of Colorado Springs. Ent housed the first NORAD command headquarters. Today the U.S. Olympic Training Center occupies the site.

Straddling the line between Aurora and Denver was the Lowry Army Air Force Base. In 1935, a group of prescient state and local officials contacted the War Department in order to secure a military airfield and training base for Colorado. The group offered to donate the Agnes C. Phipps Tuberculosis Sanatorium and adjoining property for the site; the War Department accepted the offer and began building the base, which was named for Denverite Lieutenant Francis B. Lowry, a pilot who was killed during World War I.

The base’s main focus was technical training, including aerial photography. It remained active until 1994, when it closed and transformed into a large, master-planned residential and commercial community. A few original buildings remain, including the officers’ quarters, headquarters building, and Chapel No. 1, called the “Eisenhower Chapel,” and two immense hangars, one of which houses the Wings Over the Rockies Air & Space Museum.

Twenty miles southeast of Denver, the military established the 100-square-mile Lowry Bombing and Gunnery Range in 1938; pilots based at Lowry used the range for bombing practice during World War II. The range closed in 1963, and the site became home to a Titan intercontinental ballistic missile complex. The Lowry Landfill, an EPA Superfund site today, is at the northwest corner of the range.

In Aurora is Buckley Air Force Base, named for 1st Lt. John Harold Buckley, a World War I fighter pilot from Denver who died in 1918 while on a mission over France. Shortly before World War II began, the City of Denver bought 5,740 acres of land and donated it to the U.S. Army, which quickly established an Army Air Force base, training over 50,000 airmen to become bombardiers and armorers. Buckley today is an active Air Force base with over 12,000 military and civilians working there.

Also in Aurora, Army General Hospital No. 21 (later renamed Fitzsimons Army Hospital) was built in 1918 to care for wounded World War I soldiers. A few months before America was thrust into the Second World War, the U.S. government expanded and upgraded the hospital. After the war, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower had a heart attack while golfing at Denver’s Cherry Hills Country Club in September 1955, he was nursed back to health at Fitzsimons.

Since 1903, Golden had been home to Camp George West, a training facility for Colorado National Guard soldiers. While a rifle range was located on post, artillery practice went on at Green Mountain, near Lakewood. Today Camp George West is home to the Colorado State Patrol training academy and Colorado Correctional Center.

Colleges and universities also felt the impact of the manpower drain caused by the war. The U.S. government established the ASTP—the Army Specialized Training Program—which offered a college education to gifted soldiers with the anticipation that they would become officers. As part of ASTP, the University of Colorado at Boulder opened a Japanese-language school on campus, and Colorado Agricultural and Mechanical College (later renamed Colorado State University) in Fort Collins offered veterinary training. In Colorado Springs, Colorado College offered the similar V-12 Navy College Training Program.

A 10th Mountain Division soldier at Camp Hale, March 1943.

6. We Were the Home of Soldiers on Skis

Perhaps the Army’s most unusual post was Camp Hale, sited at 9,250 feet above sea level along Highway 24 between Leadville and Minturn. From April to November 1942, 10,000 workmen built nearly 1,000 buildings in this remote valley. This 250,000-acre training ground prepared the men of the famed 10th Mountain Division for winter and mountain warfare in the Apennine Mountains of Italy in 1945.

Also at Camp Hale was a detachment of 200 WACs—the Women’s Army Corps. They did secretarial work, served as drivers and as telephone and telegraph operators, ran the post office and finance office, and more. About 75 nurses in the camp hospital and ten American Red Cross workers served at the camp as well.

Because the Army believed there would be no future need for specially trained mountain troops, it tore the camp down after the 10th departed in 1944. (There is no truth to the persistent rumor that Camp Hale was dismantled in error.) Only a few building foundations remain, but a memorial to the 1,000 mountain troopers who died in the war is at the top of Tennessee Pass, at the entrance to Ski Cooper, which once had been the division’s advanced ski-training facility.

After the war, many of the veterans returned to start the ski resorts of Aspen, Vail, Arapahoe Basin, and other ski areas around the country. The Colorado Ski and Snowboard Museum in Vail has an extensive display of 10th Mountain Division memorabilia.

Four of the "soldiers on skis" who trained for European wintertime warfare while stationed at Camp Hale near Leadville, Colorado.

7. We Lived with the Enemy in our Midst

As the war rolled on, the military brought more and more captured German and Italian soldiers to the United States, housing them in prisoner-of-war camps far from the battlefields. Across the nation, about 700 POW camps held some 425,000 captured enemy soldiers (375,000 of them German, the rest mostly Italian); from 1943 to 1946, Colorado maintained three large camps and more than forty smaller ones.

Most of the POW camps had barracks and other buildings surrounded by watchtowers, searchlights, barbed-wire fences, armed guards, and dogs. In spite of that, life for the POWs was about as pleasant as it could be. For entertainment the prisoners could watch movies, participate in sports, organize singing and theatrical groups, play musical instruments, have free medical care, and use the camp’s library facilities.

Camp Carson in Colorado Springs held the greatest number of prisoners (12,000), followed by Trinidad (2,500) and Greeley (2,000). The military established other camps in Longmont and Brighton, while Rose Hill at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal held as many as 300 who had been captured in North Africa; Rose Hill operated from November 1943 until April 1946. A Denver Post story noted that, one day, three Afrika Korps prisoners walked away from a work detail at Rose Hill and went into Denver, looking for female companionship; they were quickly rounded up and returned to the facility.

Funeral for German officer Karl Frisch, who died in July 1943 while in a POW camp near Trinidad, Colorado.

In Brighton, the Colorado Sanitary Canning Factory became a POW camp for 589 German POWs while, in Longmont, the military converted the Great Western Sugar dormitory at Third Avenue and Kimbark Street into a barracks where Italian and German POWs who worked on area farms lived.

Because America’s military draft had reduced the number of available agricultural workers, many POWs in Colorado helped tend farm fields and ranches; for their labors they earned a small daily wage that they could spend in their camp canteens.

In December 1944 The Denver Post ran a story under the headline “Denver Soldiers Overseas Don’t Like Coddling of Nazi Prisoners.” The soldiers were reacting to news that Colorado farmers were too nice to the German POWs who worked their fields.

Although fraternization was officially discouraged, many prisoners developed close bonds with individuals and families for whom they worked. Sometimes the fraternization went too far. At Camp Hale, some of the WACs got a little too friendly with the Germans, and six of the women were court-martialed.

8. We Had a Prison Camp for American Citizens

Only slightly lower than the POWs in the eyes of many Americans were the Issei and Nisei—American residents or citizens of Japanese descent. In the panic following Pearl Harbor, there were fears (unfounded, as it turned out) that many Japanese Americans were likely to be spies and saboteurs working secretly for the Japanese government.

On February 19, 1942, ten weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was persuaded to sign the controversial Executive Order 9066 that authorized the relocation of nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans from their homes along the West Coast and sent them to ten temporary “assembly centers” around the country, there to be held under guard until the war was over. To the Japanese Americans, these were little better than the concentration camps where the Nazis isolated and incarcerated Jews and other people thought to be “undesirable” or a threat to Germany.

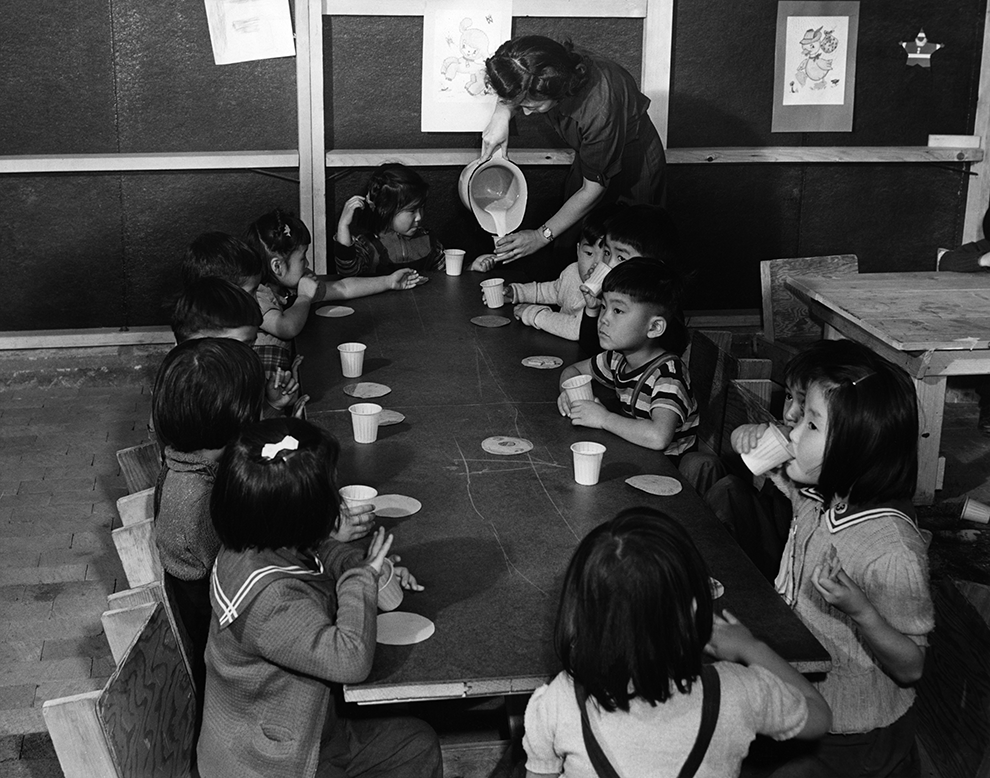

One of these camps, known as both Camp Amache and the Granada War Relocation Center, was built in August 1942 in southeastern Colorado near the small farming town of Granada in Prowers County, 140 miles east of Pueblo. Barbed wire surrounded the windblown camp, and armed guards stood watch over the internees.

Families were forced to live in cramped quarters, and the government provided three meals a day, and offered internees work to relieve the boredom: digging ditches and irrigation canals, tending gardens, and working in the mess hall. Professionals (doctors, nurses, teachers, and others) could practice their disciplines in the camp. There was a school for children and a Boy Scout troop.

There was also a compensation system that paid professionals $19 a month, skilled workers $16, and non-skilled workers $12. As the war turned in America’s favor, according to a National Park Service brochure, “From all ten camps, 4,300 people received permission to attend college, and about 10,000 were allowed to leave temporarily to harvest sugar beets” and other crops.

Nursery school teacher Sumi Kashiwagi serves milk and graham crackers to children in a recreation hall at Amache in December 1942. Photo by Tom Parker.

At its peak, Amache held over 7,300 men, women, and children, making it the smallest of the relocation camps—but the tenth largest “city” in Colorado. The government released most internees in August 1945 and closed the camp on October 15. After the war, the camp’s 550 buildings were auctioned off and removed. Today the mostly barren site is a National Historic Landmark; efforts are underway to reconstruct some of the buildings.

Proving their loyalty to the United States, scores of young men from Amache—and the other nine camps across the country—enlisted in the Army as part of the 3,000-man 442nd Regimental Combat Team. That unit, made up almost entirely of Japanese Americans, compiled a sterling combat record in Italy and France, earning more medals for courage—many of them awarded posthumously—than any other U.S. Army unit of its size. One of the men, George T. Sakato, who moved to Denver after the war, received a belated Medal of Honor from President Bill Clinton in 2000. Kiyoshi Muranaga, an internee at Amache, received a posthumous Medal of Honor after being killed in action in Italy.

One man who tried to fight this injustice and prejudice was Colorado Governor Ralph L. Carr. He refused to allow any Issei or Nisei living in Colorado to be sent to a relocation camp, believing that the Constitution protected all Americans. Likely because of his stand for human rights, he was voted out of office in 1943. But he was later memorialized by a statue in Denver’s Sakura Square, the naming of the Ralph Carr Memorial Highway along U.S. 285 from Denver to his hometown of Antonito near the New Mexico line, and the Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center in Denver’s Civic Center.

9. And, Of Course, We Served

In addition to the men of the 10th Mountain Division and the Fighting 442nd, many other Coloradans served with distinction. Ten men with a connection to Colorado were awarded the Medal of Honor—the nation’s highest award for valor in combat—six of them posthumously. One of them, Joe P. Martinez of Ault, has a statue dedicated to him in the park in front of the State Capitol. Colorado’s Medal of Honor recipients and their deeds are remembered in a display at the Broomfield Veterans Museum.

Colorado A&M University physicist Philip G. Koontz contributed to the war effort by working on the “Manhattan Project”—the top-secret atomic bomb program in laboratories in both Chicago and New Mexico. And George “Bob” Caron, who would move from Brooklyn to Denver after the war, was the tail gunner on the Enola Gay—the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and of Nagasaki three days later, unleashed previously unimaginable destruction and human suffering in hastening the end of the war in the Pacific. Japan surrendered shortly thereafter.

Another unit with Colorado roots was the 3,000-man 157th Infantry Regiment, a part of the 45th Infantry Division—made up of two National Guard regiments from Oklahoma and one from Colorado. Whereas the 10th Mountain Division saw only about three months in combat, the 45th saw 511 days of combat—in Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany—made four amphibious combat landings in the Mediterranean, and liberated the Dachau concentration camp in April 1945. And, while the 10th lost 1,000 men, the 45th had over 3,500 men killed and more than 14,000 wounded—a casualty rate of over 100 percent, as many soldiers were wounded more than once.

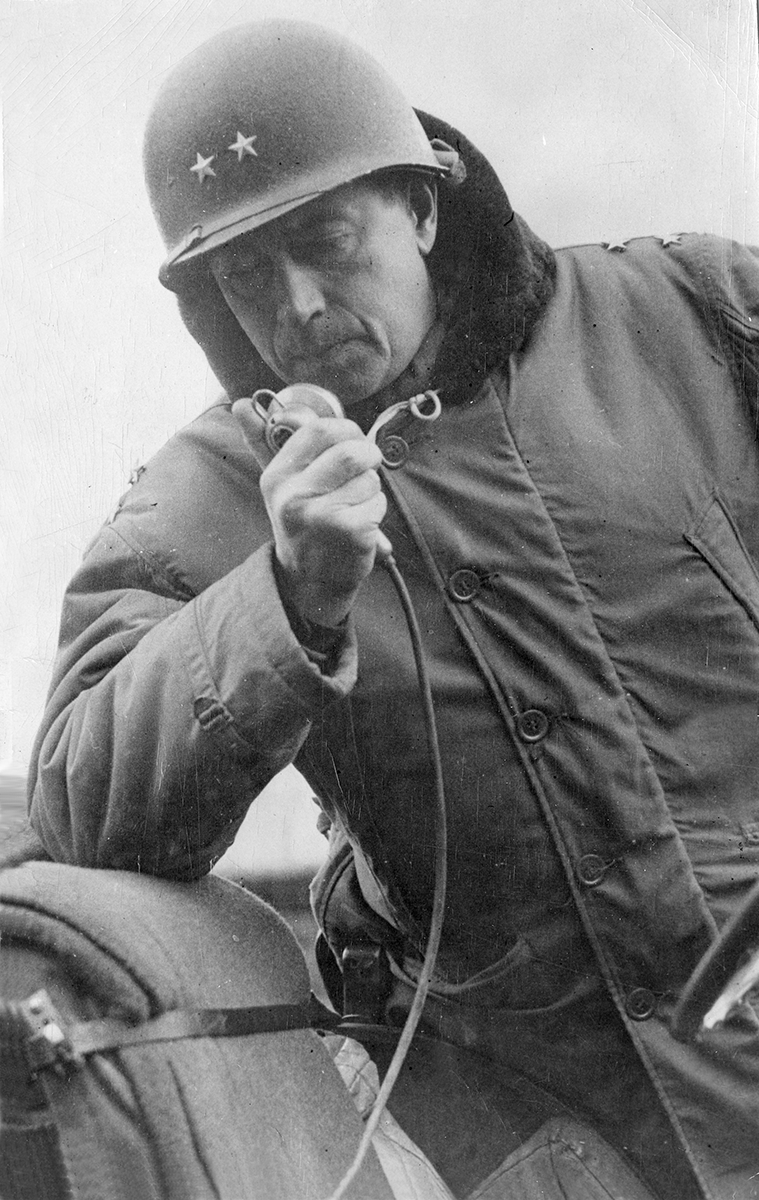

One of the thousands of Coloradans who died in combat was Major General Maurice Rose, a graduate of Denver's East High School. He became a two-star general in command of the 3rd Armored Division fighting in Germany—making him the highest-ranking Jewish officer to serve in the war. On March 30, 1945, five weeks before the end of the war in the European Theater, Rose was leading a tank column when it came under enemy fire; he was killed by a burst of machine-gun fire. After the war, Rose General Hospital in Denver was named in his honor.

Another prominent wartime Coloradan was Victor H. Krulak, who rose to three-star rank in the Marine Corps. Born in Denver in 1913, Krulak graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy. While serving as an observer in Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, he saw Japanese landing craft whose bows could be lowered to permit the discharge of troops. So unique was the idea that he passed it along to New Orleans boat builder Andrew Higgins, who developed the idea; the U.S. military adopted the design, and the LCVP (Higgins boat) was born. Krulak repeatedly distinguished himself in combat in the Pacific Theater, and served later in Vietnam.

10. We Liked Ike (And He Liked Us)

Undoubtedly the most well-known individual with Colorado ties was Dwight D. Eisenhower. A year after graduating from West Point in 1915, he married Mamie Doud, daughter of a prominent Denver family (her family home still stands at 750 Lafayette Street). They honeymooned at Eldorado Springs near Boulder.

Stationed from December 1924 to September 1925 at Fort Logan, in the Denver suburb of Sheridan, “Ike” went on to become the supreme commander of SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) and oversaw all forces in the European Theater of Operations. Seven years after the war, he became the thirty-fourth President of the United States and enjoyed spending his summers in Colorado, with Lowry Air Force Base as his “Summer White House.”

The Eisenhower family return to their home on Lafayette Street in Denver on May 16, 1958. Photo by Albert Moldvay.

11. We Went a Little Crazy for Peace

On May 8, 1945—Victory in Europe Day—Nazi Germany officially surrendered. The Japanese did likewise on September 2, 1945, in a formal ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. Throughout the nation and Colorado, people laughed, cheered, celebrated, got drunk, danced, paraded in the streets, and went to church to give thanks.

On August 18, the national wartime speed limit of 35 miles per hour was lifted. Two days later the front page of The Denver Post sported an eight-column banner headline: “Nylons & Girdles Due Any Day Now”—much to the relief of fashion-conscious women. The government suspended the rationing of shoes and ceased most food rationing by year’s end.

Two days of celebrations—marred by drunken brawls, car accidents, and small fires—broke out throughout Denver and other Colorado cities and towns as the end of the war was in sight. Scotty Wallace, head of Denver’s street-cleaning department, could only shake his head at the mounds of paper and broken glass that littered the city’s streets—worse, he said, than after the Armistice in 1918.

Pueblo, too, held a massive victory jubilee on August 26, complete with parades, marching bands, and fireworks at the Colorado State Fairgrounds.

To the great relief of people around the world, the war that had claimed 60 to 80 million lives was at last truly over.

And Colorado had done its part to bring about the Allied victory.

More from The Colorado Magazine

“Is America Possible?” The Space Between David Ocelotl Garcia’s and Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Worship

Colorado Is My Classroom More than a century ago, open-air classrooms had a moment in response to another pandemic. Then it was tuberculosis, another era-defining airborne pathogen that attacked the respiratory system. And the results were encouraging. Could fresh air be part of the solution to school in the time of coronavirus?

Immigration to Colorado: Myth and Reality For most of its history, America has been a haven for those seeking a better life and a refuge for those fleeing for their lives. Indeed, since its inception, America has been an inspiration to others, a place where the downtrodden could find hope. Among the proponents of immigration was President John F. Kennedy, who laid out his inclusionary vision of America in his 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants.