Story

Immigration to Colorado: Myth and Reality

The United States could be described as a nation of immigrants seeking to realize the American Dream. But how much of what we know about Colorado's pre–World War II immigrants is deep-seeded mythology?

For most of its history, America has been a haven for those seeking a better life and a refuge for those fleeing for their lives. Indeed, since its inception, America has been an inspiration to others, a place where the downtrodden could find hope. Among the proponents of immigration was President John F. Kennedy, who laid out his inclusionary vision of America in his 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants.

Kennedy’s paean to immigrants notwithstanding, the history of immigrants in America has been a fraught one. Their story is more complex than the proponents of immigration would have it. Instead of working together to transcend their cultural differences to achieve the ideals embodied in America’s founding documents, immigrants brought with them their inherited prejudices of race and nationality.

As historian Thomas Andrews notes in Killing for Coal: “The Welsh and Scots despised the Irish, the French bore a grudge against the Germans, and the Germans claimed superiority over the Poles, who could not forgive the Austrians, who despised African Americans, who distrusted Yankees, who saw Hispanos as dirty, lazy, and primitive.”

Indeed, immigrants have often contended with each other in their pursuit of the American Dream.

Of course, another president, Donald J. Trump, has more recently been the country’s most prominent opponent of immigration. Like many in the past, he has often cast immigrants as a burden on the rest of society. Is that really the case?

Where Immigrants Came From

A mountainous and arid area, Colorado initially attracted few colonizers. Up through the first half of the nineteenth century, it was a relatively sparsely populated place, inhabited mainly by Native Americans, who had long occupied the area, and Hispano settlers, who traced their origins in the region back to the seventeenth century. Before the Territory of Colorado could become an integral part of the United States, it needed settlers willing to face the daunting challenge of an inhospitable landscape and climate and, later, to weather the area’s boom-and-bust economy. Many of the people who took on this challenge were immigrants and their descendants.

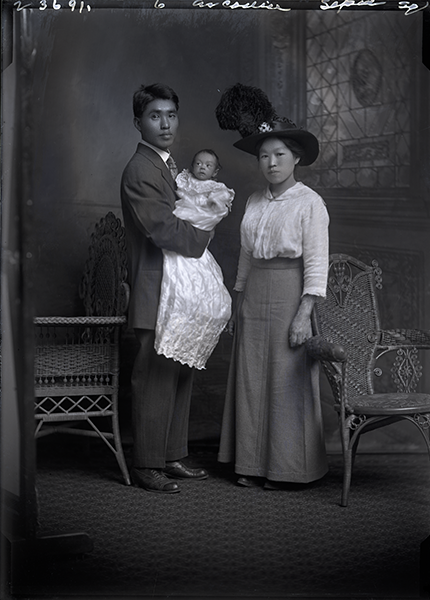

Florence Bath (shown circa 1920) immigrated from Scotland to the town of Avalo in Weld County, Colorado.

What started the colonization of Colorado was the 1858–61 Colorado Gold Rush, also known as the Pikes Peak Gold Rush. This initiated a flood of habitation into what was once deemed an uninhabitable region. In the wake of the gold rush and in the midst of the secession of the southern states, which precipitated the Civil War, the US government established the Territory of Colorado on February 28, 1861. The creation of the Colorado territory enhanced federal control of the Intermountain West and its resources, protecting them from depredations by southern secessionists.

By 1870, immigrants constituted 16 percent of Colorado’s population. For most of them, westward migration was a two-stage process: first they migrated from the East Coast to the Midwest, then they migrated again to the Interior West. They were welcomed in labor-starved Colorado. Edward M. McCook, Colorado Territorial Governor in 1869–73 and 1874–75, certainly appreciated their value. As a Union general in the Civil War, he readily acknowledged the important role that immigrants played in the Union’s victory against the Confederacy and considered them the solution to Colorado’s chronic labor shortage. In his 1870 message to the Territorial Legislature, McCook observed that “those new States of the West, like Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota, which have made organized efforts to secure European emigration, have increased in population and wealth beyond all precedent in the history of our country.” He further observed that European immigrants were interested in coming to Colorado, noting that he had received communications from “two German colonies containing over two hundred families each, and from one containing forty families” inquiring about agricultural and other resources of the territory.

From the information provided by the 1870 Census, it is evident that the majority of immigrants living in Colorado who had been counted a decade earlier in the 1860 Census were the offspring of immigrants who had settled in nearby midwestern states as part of an earlier wave of immigration. The Census Bureau appreciated their immigrant origins as well, so in 1870 the Census began to enumerate the number of descendants of earlier immigrants. It noted the value of “ascertain[ing] the contributions made to our native population by each principal country of Europe; to obtain . . . the number of those who are only one remove.” Because most of the immigrants who came first were males, the descendants of immigrants tended to have foreign-born fathers and native-born mothers. As people moved westward, there was increasing intermarriage. Of the Coloradans enumerated in the 1870 Census, 23 percent had foreign parents, and an additional 26 percent had one parent who was foreign.

Most of the migrants were young men who migrated from nearby Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, and Iowa. A significant number also migrated from as far away as New York and Pennsylvania. In all likelihood, those from New York and Pennsylvania were also descendants of immigrants: Irish (the so-called famine Irish) who sought to escape the urban ethnic enclaves into which they were crowded and German (the so-called Pennsylvania Dutch or Deutsche) who sought land to farm. Because of proximity, midwestern descendants of immigrants were able to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by Colorado. And the advent of rail transportation enabled those living on the East Coast to do so as well. They were persuaded that a better life awaited them in the Colorado Territory.

Many of these descendants of immigrant Americans identified with their ethnic group first and spoke the group’s language rather than English. As the 1870 Census itself noted, it was commonplace to refer to people by their ethnicity rather than their nationality, that is, where they were born. With the end of the Civil War (1861–65), these descendants of immigrants, along with other Americans, would increasingly identify with the nation rather than the state or their ethnic group, a phenomenon that was reinforced by civic education taught in American schools.

Why Immigrants Came

A variety of push/pull factors led to immigration to America and Colorado, and these changed depending on the prevailing circumstances. The national narrative emphasizes the search for freedom that brought early colonists to America. In 1883, Emma Lazarus described immigrants as the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” This is reflected in the 1860 US Census that described immigrants as those “impelled to seek . . . a refuge from the persecutions of religious bigotry and political exclusion at home.” English Pilgrims, French Huguenots, and German “Forty-Eighters,” for example, were religious and political dissenters who sought refuge in America.

A more important reason the majority of immigrants came to America was poverty. Many were driven from their homelands because of an unfavorable land-to-people ratio. Population growth was a driving factor. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were about 900 million inhabitants on earth. Within a century that number had climbed to 1.6 billion. The grim reality in many areas of the world was that there were now too many people on too little land to support them, a situation exacerbated by adverse climatic changes. For example, in the 1800s, southwestern Germany suffered from extreme weather conditions that resulted in a series of disastrous crop failures. In the early 1900s, so-called Volga Germans—Germans who had migrated to Russia—were eventually forced by famine and politics to migrate again. For those wishing to escape this precarious existence or live at something better than a subsistence level, the solution was to become economic immigrants. Many Germans voluntarily went to America in search of a materially better life for themselves. Many of them settled in Colorado’s farm country.

As the 1860 Census observed, for immigrants America was a place “more than anywhere else, [where] every man may find occupation according to his talents, and enjoy resources according to his industry.” And that primary resource was “land beyond the capacity of the people to till, and consequently cheap.” This vision of plentiful land was encouraged by the Homestead Act (1862), a bill signed by President Abraham Lincoln to stimulate western migration by providing settlers 160 acres of public land. To receive ownership of their homesteads, settlers had to be US citizens and complete five years of continuous residence on the land. With this incentive, immigrants came in droves looking for land they could call their own. In 1880, immigrants represented only 13 percent of the national population, but 23 percent of those who settled in the American West.

Their settlement of the land was expedited by the building of the Transcontinental Railroad (1863–69), a 1,912-mile railroad line that connected the US rail network at Council Bluffs, Iowa, to San Francisco, California. The railroad provided a comparatively cheap and fast way for people in the United States and from around the world to go beyond the 100th meridian to Colorado. Along with another advance in technology—steamships—railroads brought America and the Interior West closer than ever before to immigrants. Advances in modern technology facilitated the settlement of the American West. Railroads and steamships made America and the Interior West closer than ever to people around the world.

The Transcontinental Railroad, which promoted immigration to the American West, was also built by immigrants, mainly Chinese who worked on the Central Pacific and Irish on the Union Pacific. Arguably, the over 20,000 Chinese who worked on the railroad had the worst of it since they had to negotiate the Sierra Nevada Mountains. As Ava Chin, a descendant of a Chinese railroad worker, described it in a May 26, 2019, article in the Washington Post, the workers “risked their lives hammering and detonating gunpowder, surviving avalanches and extreme conditions—engaging in the kind of backbreaking, chisel-to-granite ‘bone-work’ that others refused to do.” The Chinese and Irish immigrants can be credited with unifying the nation economically and culturally. After completing the railroad, many immigrant workers remained in the Interior West, making their way to Colorado and the other Intermountain states, where they contributed significantly to local economies by working in the mines, on railroads, and in other occupations.

Another sizable group to migrate to America were those who involuntarily immigrated as a matter of life and death. They were refugees. The best known were the Irish, who fled rural areas because of the Great Potato Famine. The famine claimed the lives of more than a million Irish peasants who died from starvation and disease. Ironically, food was available in Ireland to feed them, but their English landlords exported it abroad. As journalist Timothy Egan has recently observed, some of the English thought that “a merciful God was doing a favor by killing off the starving masses” who came from a country infested with crime, famine, and disease. Penniless Irish peasants thus joined the exodus abroad, ending up in unfamiliar urban enclaves on America’s eastern seaboard. In the first half of the nineteenth century, some three million immigrated to America.

What Immigrants Did

By the 1870s, 74 percent of those living in Colorado were born in America, mainly descendants of an earlier wave of immigrants; 26 percent were newly arrived immigrants.

The 1870 Census grouped these immigrants and their descendants into four major employment categories: agriculture, professional and personal services, trade and transportation, and manufacturing and mining. Most were engaged in some sort of physical labor: agricultural laborers (with immigrants comprising 41 percent of that workforce), laborers (at 53 percent), officials and employees of railroad companies (34 percent), and miners (46 percent). Among the laboring masses were large numbers of British and Irish, viewed at the time as boasting superior strength. Lacking the capital to start farms or the skills needed to farm the arid high plains of Colorado, they had few alternatives but to work as common laborers. In this capacity, immigrants played a significant role in developing the territory’s economy, doing the work necessary to make it a wealth-producing area and building the infrastructure necessary to make the area accessible to the rest of the nation. They laid the economic foundation necessary for the Territory of Colorado to become the State of Colorado.

Immigrants arrived at a crucial moment in Colorado’s history. Besides contributing to the economy, their very presence provided the numbers needed for Colorado to become a state. Jerome Chaffee, territorial representative from Colorado in Congress, was able to push through the enabling act for statehood only because he could convince his congressional colleagues that the territory had the required 150,000 people in 1875 due to a rapid increase in population. In 1870, according to the Census, Colorado’s population stood at a mere 39,864; by 1880, the population had increased almost five times over to 194,327 people (20 percent of them first-generation immigrants), making it the most populous as well as prosperous mountain state. Colorado became the nation’s thirty-eighth state on August 1, 1876.

Changing Patterns of Immigration

The pattern of immigration to Colorado was changing, however. From the nativist perspective, the change was ominous. Though there were comparatively few immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, and Asia in the 1880s, the general populace in Colorado, including earlier groups of immigrants, viewed the newcomers with apprehension. Indeed, the populace believed the new arrivals would overwhelm them. Their response to these later immigrants was out of proportion to any real threat the newcomers actually posed to their livelihoods or culture. Different groups of immigrants faced different levels of discrimination. While the bigotry against immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe was severe, the discrimination lasted longer and was far worse for people of color. Traditionally, Asians, along with Black people, Latinos, and Native Americans, were stigmatized because of their race rather than ethnicity.

Discrimination against newcomers has been a recurring pattern in the history of immigration. Earlier European immigrant groups, such as the Irish and Germans, also perceived succeeding groups of new immigrants this way, even though they themselves had experienced discrimination. Compared to British immigrants, who were Anglo-Saxon and Protestant, the Irish were viewed unfavorably for being Celtic and Catholic, their Catholicism being considered their most unfavorable characteristic. The Irish were also racialized, described as dark, brutish, and simian-like.

When different immigrant groups found themselves in economic competition, the perception of racial or ethnic otherness provided fuel for heightened antagonism. In Gilpin County, for example, Cornish and Irish immigrant miners found themselves competing with each other. The Cornishmen (from Britain) had arrived the earliest and had been recruited for their expertise in sinking shafts and tracing veins. But they felt that their livelihood was being threatened with the arrival of the Irish, who were being paid less. The antagonism of the Cornishmen toward the Irish was exacerbated by what was considered a natural antipathy based on cultural and religious differences. As Lynn Perrigo observed in her 1937 Colorado Magazine article on the Cornish and Irish conflict in Gilpin County, “it did not take many drinks to precipitate a fight between members of these two groups.” Sometimes, such ethnic differences resulted in violent clashes such as the Philadelphia Nativist riots in 1844, a result of rising anti-Catholic sentiment and the growing presence of Irish Catholic immigrants in the City of Brotherly Love. Anti-Catholicism persisted in America to at least the sixties, when John F. Kennedy’s election was dogged by allegations that as a Catholic, he was a de facto agent of the Pope.

The Germans were similarly viewed unfavorably for being Teutonics and Catholics. They were feared and disliked for allegedly being socialists with violent tendencies and then for being potential subversives during World Wars I and II. Early on, during colonial times, the venerable Benjamin Franklin took a dim view of their language and customs, complaining of the adverse influence they were having on Pennsylvania, though it should be noted that they, along with the Swiss, were the ones who opened up Pennsylvania’s backcountry.

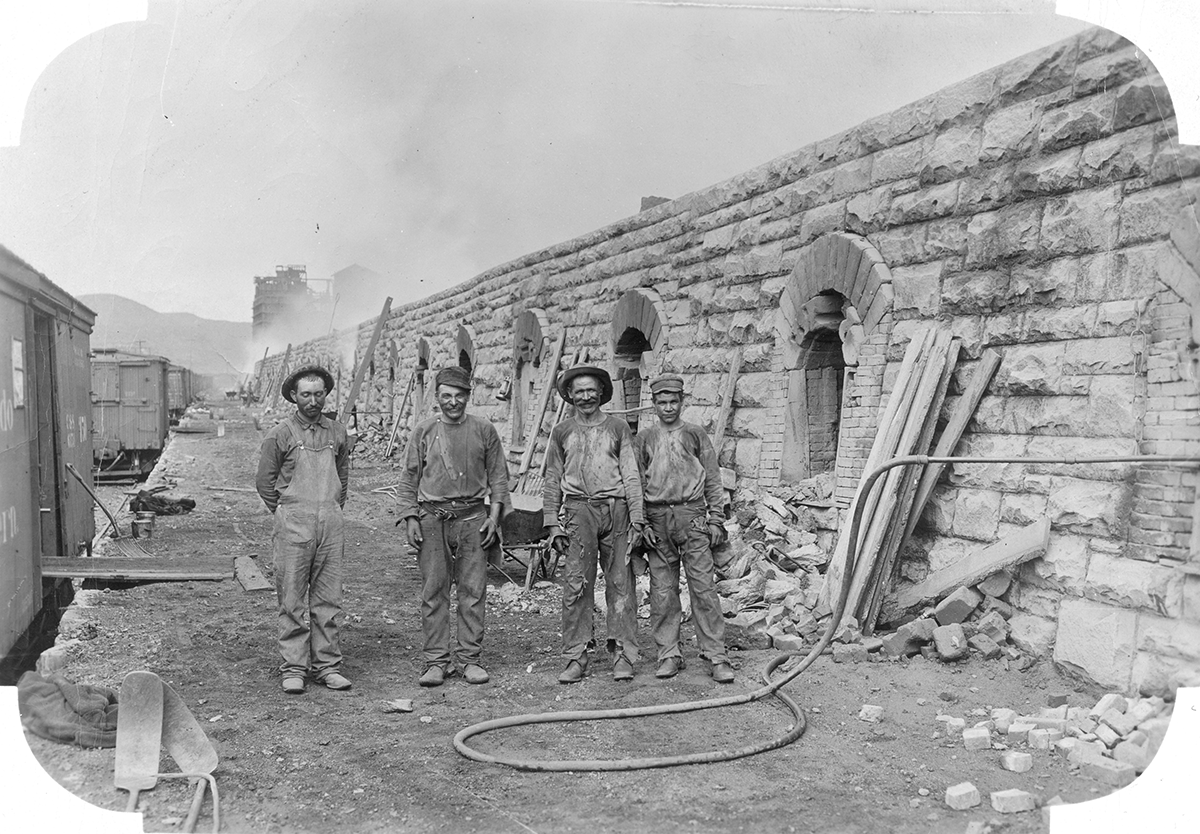

Italian and/or Hispano coal miners pose in front of coke ovens at Tercio, Colorado, in Las Animas County, circa 1910. Photo by Almeron Newman.

Generally speaking, native-born Americans (themselves descendants of immigrants) condemned Irish and German immigrants, considering them unalterably foreign and inferior. The national nativist Know-Nothing Party (1844–60) opposed their immigration to America, seeing them as an existential threat to the American way of life. As far as nativists were concerned, the Irish and Germans were suspect people intent on stealing American jobs. The Know-Nothings tried to disempower Irish and German immigrants already in the country by requiring them to be residents for twenty-one years before being eligible for citizenship. Fortunately, this did not come to pass.

As time went on, the Irish, Germans, and other white ethnic groups assimilated into mainstream society. They became citizens, attained political power, and moved up the economic ladder. Through ethnic solidarity, Irish immigrants advanced themselves politically whenever they could. For example, in 1881 in Denver, though most Irish were Democrats, they banded together to elect a countryman, Robert Morris, as Republican mayor.

White ethnic assimilation was facilitated by intermarriage, which served to attenuate the individual’s original ethnic identity by combining it with that of another. As previously mentioned, immigrants married native-born Americans at a high rate. Contrary to nativists’ conviction that immigrants were unassimilable, immigrants always assimilated into American mainstream society to some extent for reasons of survival, if nothing else, and their descendants assimilated to an even greater extent, learning to speak English (the American version, of course), embracing American customs, and espousing American values as the way to achieve security and success for themselves and their families. Ironically, this included the acceptance of the mainstream’s prejudices toward various ethnic and racial groups.

Take the Irish, for example. As they moved westward, their socioeconomic circumstances improved steadily. They moved up from the bottom of the economic ladder to its middle rungs and higher, enjoying a status they never could attain in East Coast urban ghettos. “An Irishman might be described as a lazy, dirty Celt when he landed in New York, but if his children settled in California [or in Colorado] they might well be praised as part of the vanguard of energetic Anglo-Saxon people poised for the plunge into Asia,” as Reginald Horsman has noted in his study, Race and Manifest Destiny. However, Irish upward mobility came at the expense of other groups. The Irish stood shoulder to shoulder with older immigrants in opposition to other immigrants who were viewed as being even more foreign than they were.

Southern and Eastern European immigrants were denigrated for belonging to an alien culture, exhibiting exotic customs and having a low standard of living. For example, Italians, most of whom were from southern Italy, were among the most unpopular immigrants in Colorado. They were recruited as cheap labor for mines, smelters, and railroad construction gangs. With the promise of good pay and safe working conditions, Italian workers immigrated to America looking for economic opportunity. Many were recruited by labor contractors known as padrones during the great railroad construction period from 1880 to 1895. By 1890, Italian immigrants could be found working in industrial centers and mining camps in Colorado. Like other immigrants, the Italians endured what they did to earn money to send back home to support their families, or to save enough to enable them to buy farmland or open a business when they returned to their native land. Many succeeded in improving their economic circumstances. Even with the hardships they experienced, Italians and other immigrant workers wrote letters to friends and relatives about the high wages that could be earned in America. In comparison to their homelands, America was the place to make money.

Though Italians suffered discrimination, exploitation, and hostility, they did have one advantage. They were Europeans and were considered whites, which paved their way to acceptance into American society. The Italians eventually found common ground with other European immigrant groups in their opposition to the capitalists who exploited them. Many of them participated in the labor movement in Colorado, where they engaged in labor disputes. Some of the disputes ended violently, such as the infamous Ludlow Massacre on April 20, 1914, where twenty-one people were killed, mostly children and women.

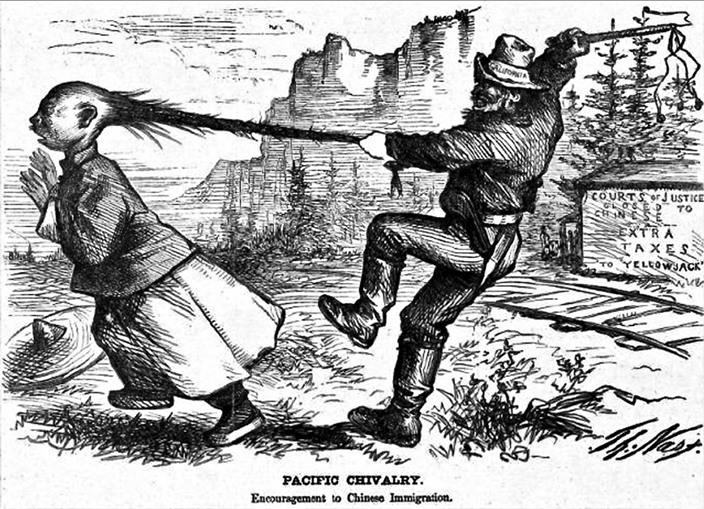

Unlike Irish and Italian immigrants, the Chinese were ostracized because of their race. But they were condemned for being racially rather than ethnically different, placing them squarely in the middle of the longstanding black-and-white binary that has shaped race relations in America ever since its founding. The Chinese bore the dual burden of being new immigrants as well as a people of color. The driving force behind the anti-Chinese movement was mainly racial antagonism toward Asians. As John Higham notes in his classic, Strangers in the Land:

No variety of anti-European sentiment has ever approached the violent extremes to which anti-Chinese agitation went in the 1870s and 1880s. Lynchings, boycotts, and mass expulsions still harassed the Chinese in 1882. . . . Americans have never maintained that every European endangers American civilization; attacks have centered on the “scum” or “dregs” of Europe, thereby allowing for at least some implicit exceptions. But opponents of Oriental folk have tended to reject them one and all.

The Chinese tried to defend themselves against this hostility but were handicapped. Chinese (and other Asians) were among the most vulnerable because they suffered the disadvantage early on of being declared aliens who were ineligible for citizenship. In 1870, Congress had passed a Naturalization Act that limited naturalization to whites and Africans. Denied the right to vote and to hold political office, Chinese were unable to protect themselves from their nativist enemies. For them, “Not a Chinaman’s Chance” was more than just an expression.

Politicians demonized Chinese immigrants as a way to gain people’s votes, and union organizers vilified them to build up their incipient labor movement. Together, leaders of these groups waged a vitriolic campaign against the Chinese. They encouraged the lynching and expulsion of Chinese, and the boycott of Chinese businesses. Their enmity toward the Chinese, couched in terms of solutions to the so-called Chinese Question in the 1870s, centered on the need for restrictions on their immigration to the United States. The exclusion of the Chinese from the country in 1882 was the harbinger of a restrictive immigration policy. It was only a short step from the racism that was the basis of this policy to the establishment of an ethnic hierarchy that would later restrict new immigrant groups from Southern and Eastern Europe during the 1920s.

The nativists did not wait for an answer to the “Chinese Question.” In the wake of the Panic of 1873 and the worldwide depression, nativists in Colorado used the Chinese as scapegoats, declaring “the Chinese must go!” Nativists engaged in a campaign to drive them out of Colorado’s mining communities. In Leadville, where the silver boom began in 1877 and one third of the miners were Irish, the Chinese were forbidden from entering the town on pain of death. In Como, during the so-called Chinese-Italian War (1879), Italian miners attacked and expelled Chinese miners whom they feared were being brought in to replace them, vowing to kill them if they returned.

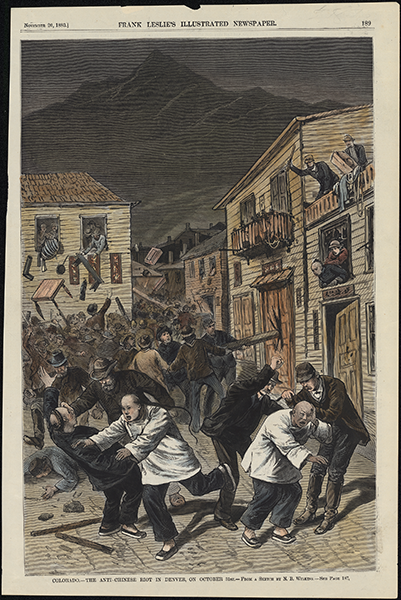

The hate campaign against the Chinese in Colorado culminated in the Denver anti-Chinese race riot of October 31, 1880. An estimated three to five thousand people, approximately 10 percent of the city’s residents, descended upon the city’s Chinatown to rape and pillage. They sought to kill or expel Chinatown’s 450 residents. Given that Chinatown was located in an area of the city with a large immigrant population, comprising between 30 to 40 percent of the population, it is highly likely that many of the rioters were fellow immigrant workers. After the race riot, there was never a recurrence of large-scale violence against the Chinese in Colorado, though there were a series of isolated incidents. Ethnic cleansing of Chinese continued.

An engraving by N. B. Wilkins in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of November 20, 1880, depicted Denver’s Anti-Chinese Riot

The Denver anti-Chinese race riot contributed to the passage of the federal Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which blamed the Chinese for local disturbances and held them responsible for the violence against them, adding insult to injury. The Exclusion Act placed a ten-year moratorium on the immigration of Chinese laborers from entering the country as a way to ensure social order. By 1902, anti-Chinese groups were able to convince the US Congress to make the Exclusion Act permanent.

Colorado’s need for workers persisted, however. So Japanese and other Asians immigrants were recruited to replace the Chinese. At the same time, anti-Asian groups lobbied to exclude all Asian immigrants from the country. Unions used the race card to foster worker solidarity among its members at the expense of racial groups such as Asian and Latino immigrants, Blacks, and Native Americans. The Western Federation of Miners, for instance, publicly opposed the continued presence of “Asiatics” in the United States” in 1901.

Golden Door to Guarded Gate

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act had consequences well beyond the Chinese. As an opponent of the original legislation, Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar (Republican), noted in 1882 that the act legalized racial discrimination. It was the first law enacted targeting a specific group of people to prohibit them from immigrating to the United States. Before then, there were no significant restrictions on immigration, and those that existed were simply ignored. The Chinese Exclusion Act signaled the beginning of the end of free immigration to the country.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the character of immigration to the United States and Colorado had changed. In 1890, immigrants constituted 20.3 percent of Colorado’s population and those with a foreign parent constituted 33.02 percent, a significant portion of the population. Immigrants from Northern and Western Europe began to decrease while those from Southern and Eastern Europe began to increase, with some groups like the Italians present in numbers almost equal to those from Great Britain and Germany.

Between 1890 and 1910, immigrants to Colorado from Southern and Eastern Europe rose steadily but did not surpass those from Northern and Western Europe. The number of immigrants from Asia continued to be comparatively small. By 1910, 38 percent of the immigrants were from Southern and Eastern Europe, and 51 percent were still from Northern and Western Europe, while only a handful were from Asia, mainly Japan. Much of this change had occurred since 1900, with the numbers of immigrants coming from Italy, Russia, and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire showing the largest increases.

The influx of immigrant workers from Southern and Eastern Europe compensated for the decrease of those from Northern and Western Europe, some of whom had benefited from upward mobility and were now working in a managerial capacity. A significant portion of all European immigrants, however, continued to work as laborers, particularly in the mining industry, which remained the preeminent part of the state’s economy. Mine workers accounted for fully 10 percent of those employed, with workers from Southern and Eastern Europe filling the most dangerous and onerous occupations in the mines.

After World War I (1914–18), emigration from Southern and Eastern Europe to the United States was severely restricted because of the post-war economic depression and a rising isolationist sentiment that had emerged across the country. As was the case with the earlier Chinese Exclusion Act, people called for immigration restriction because of the widespread fear they would lose their jobs and suffer a decline in their standard of living.

Justifying the call for immigration restriction were eugenicists who created a hierarchical taxonomy of races. They placed Nordics at the top of the hierarchy, justifying this ranking with pseudo-scientific arguments about Nordic genetic supremacy. According to eugenics adherents, Nordics from Northern and Western Europe were superior in every way that mattered and should be encouraged to immigrate to America, while “Mediterraneans” from Southern and Eastern Europe were inferior and should be discouraged from immigrating. A corollary to this was that intermarriage with people belonging to intellectually inferior and morally degenerate groups inevitably led to the birth of weaker rather than stronger progeny. Nativists claimed that eugenics proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that certain disparate groups of people did not mix well and when they did, the result was degeneration.

On the one hand, eugenics adherents advocated what was called “positive eugenics,” emphasizing selective breeding of those at the top of the racial hierarchy, and on the other, “negative eugenics” to restrict or end the breeding of those on the bottom. Tragically, this movement would lead to such malevolent practices as the sterilization of Black people in America and the genocidal extermination of Jews in Europe. Not surprisingly, to prevent intermarriage among races, many states kept supportive anti-miscegenation laws on their books until they were struck down by the US Supreme Court in the case of Loving v. Virginia in 1967 as violations of the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the 14th Amendment.

On the basis of bogus genetic science, nativist leaders called for the country to change its time-honored policy of free immigration and adopt restrictive policies to prevent “inferior” people from entering the country. The federal government responded by passing a series of measures to do so. The laws were patently prejudicial from the get-go, favoring the old immigrants from Northern and Western Europe and disfavoring the new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe.

At first, Congress tried to reduce the number of entrants with the passage of a Literacy Act in 1917. The act required that all immigrants be able to read or write English or some other language, and created the “Asiatic barred zone,” which prevented immigrants from most of Asia and the Pacific Islands from emigrating to America. But this proved inadequate for the nativists, so they persuaded Congress to institute the notorious “national origins” system to restrict immigration even further. In 1924, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, which limited the number of immigrants to two percent of those living in the United States according to the 1890 decennial census. The act also excluded all Asians, including Japanese, from entering the country. In essence, the measure sought to return the country to what it was like before 1882, when the majority of the population consisted of white people from Northern and Western Europe. This new immigration barrier was erected with the complicity of older immigrant groups from Northern and Western Europe, who saw it in their interest to disavow their past and direct animus toward newer immigrant groups from Southern and Eastern Europe. By so doing, the earlier immigrant groups deflected criticisms from themselves onto the new arrivals while also affirming their assimilation into mainstream American society. The older immigrants and their descendants dealt with this cognitive dissonance by declaring that the new immigrants were somehow different from their own immigrant group, though their criticisms of the new immigrants were eerily similar to those that had been leveled against their own ethnic group in the past.

In 1929, the government made this restrictive immigration system permanent with the National Origins Clause, limiting the total number of so-called quota immigrants to no more than 150,000 a year. The immigration system put in place served as an invisible wall to exclude emigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and other parts of the world, notably Asia. Given the antipathy toward the new immigrants, it is hardly surprising that in 1931, for the first time in American history, the number of migrants leaving the country exceeded those entering the country. Consequently, from 1930 to 1970, immigrants as a percentage of Colorado’s population began to decrease.

Fortunately for Colorado, there were no quotas or limitations applied to immigrants from the Western Hemisphere, that is, Canada and Latin America. Immigrants from Latin America, mainly from Mexico, continued to enter the United States in general and Colorado. More than half of the net increase in immigrants to the United States from 1910 to 1930 was due to immigration from Mexico. By 1900, an estimated 12,816 immigrants from Mexico had come to the Centennial State, joining the large Hispano population who were already here. The Hispanos were originally Mexican inhabitants who had been incorporated into the United States and given American citizenship as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Altogether there were 57,676 Coloradans of Mexican ancestry in 1930 when they were first counted as a separate census category. Previously, their numbers had been included with the white population. But as the 1930 Census noted, “Because of the growing importance of the Mexican element in the population and among gainful workers, [the Mexican population] was given a separate classification.” Between 1910 and 1950, Mexican immigrants constituted a significant proportion of the state’s population, reaching a highpoint of 13.4 percent by 1930.

The Hispanos and the Mexican immigrants played an important role in the state’s economy. They could be found working in the coal mines, in the smelters and steel mills, and in the beet fields. As coal consumption increased exponentially during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, coal mine owners went to Hispano communities in Colorado and throughout the Southwest to recruit workers.

As seasonal agricultural workers, Hispanos and Mexican migrants were essential to Colorado’s sugar beet industry, which became the mainstay of the state’s commercial agricultural economy after World War II. Working in the beet fields required workers to perform some of the most physically demanding and disagreeable jobs in the agricultural sector. Hispano and Mexican migrant workers engaged in other types of back-breaking “stoop labor” as well.

Between 1910 and 1930, it has been estimated that more than 30,000 Mexican migrants worked in the state’s sugar beet industry. This number is far greater than was recorded in the Census, suggesting that many may have been undocumented immigrants. Even though Colorado farmers needed them, racial antagonism towards Mexicans and other Latinos increased. This led to the strange and short-lived border incident in 1936 when Governor Edwin “Big Ed” Johnson tried to halt mainly New Mexicans from entering Colorado to work in its beet fields. An “America First” isolationist, Johnson declared martial law and sent 800 National Guardsmen to police Colorado’s 370-mile southern border to blockade what he called the invasion of “aliens” and “indigents” from New Mexico. Implicitly, Johnson was questioning whether New Mexicans were really Americans or at least the type of Americans who were welcome in Colorado. His pretext was to save jobs for Coloradans, but the blockade was actually an act of political posturing intended to curry favor with voters. It was also a brief effort, as New Mexico Governor Clyde Tingley announced a boycott of Colorado products in response, and Johnson met with push-back from Colorado farmers and ranchers who had difficulty recruiting enough low-wage workers from within the state. After ten days, Johnson rescinded his xenophobic executive order.

As a result of labor shortages during World War II, when farm workers left to join the armed forces or went to work in the better-paying defense industry, sugar beet companies as well as farmers in general once again relied on Mexican workers. They were recruited through the Bracero Program (the Spanish term bracero means “one who works using his arms” or “manual laborer”), the largest contract labor program in US history. In an effort to provide farms and factories with the workers they sorely needed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the program in 1942. It was agreed that the braceros would receive a minimum wage of 30 cents an hour, be given decent living conditions, and be protected from racial discrimination such as being excluded from segregated “whites only” public facilities. The braceros traveled around the country, working wherever their labor was needed. Unfortunately, employers often violated the agreements, failing to provide them with adequate housing, health care, safe working conditions, and even wages. Most braceros endured the exploitation and discrimination because they believed correctly that they would make more money in the United States than they could in Mexico. They saw it as an opportunity to improve their family’s prospects. The monies earned in the United States allowed them to own a home, open a business, start a farm of their own, and send their children to school. Contrary to what some critics believed, the braceros did not adversely affect native-born farm workers, and when the braceros no longer were available, the economic situation of native-born farm workers did not improve.

As a result of the program’s success, American farmers came to rely on Mexican migrant workers. When the Bracero Program ended in 1964, they complained to the US government that Mexican workers had done jobs that Americans refused to do and that their crops would rot in the fields without them. This situation continues to the present day. Ever since then, Mexican workers have been coming to the United States and Colorado to work, some on H-2A temporary work visas and others as undocumented migrant workers.

With the passage of the discriminatory immigration laws of the 1920s, the United States was able to prevent so-called undesirable peoples from entering the country for several decades. It would take World War II and the Cold War to end these prejudicial laws and replace them with fairer ones. These new laws significantly changed the character of immigration to Colorado. But by the early twenty-first century, some Americans would, once again, advocate that immigration in general be curtailed and that some immigrants be denied entry into the country.

For Further Reading

Works referenced are John F. Kennedy, A Nation of Immigrants (New York: Harper Perennial; Reprint Edition, 2008); Thomas G. Andrews, Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008); Governor Edward M. McCook, “Female Suffrage,” in “Message to the Colorado Legislature, January 4, 1870,” in Council Journal of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Colorado, Eighth Session (Central City, CO: David C. Collier); Ava Chin, “Racists kicked my Chinese ancestor our of America. He still loved the railroad he worked on.” Washington Post, May 26, 2019; Timothy Egan, “Send me back to the country I came from,” New York Times, July 19, 2019; Lynn Perrigo, “The Cornish Miners of Gilpin County,” The Colorado Magazine 14 (May 1937): 92–101; Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981); and John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (New York: Atheneum, 1974).

This essay is adapted from “Immigration to the Intermountain West: The Case of Colorado,” presented at the 9th Annual Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences & Education Conference, Honolulu, January 2020. It has been published in the conference’s online proceedings.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Immigration to Colorado Myth and Reality, Part Two Immigration is ever-relevant in the United States and Colorado. Here, our former State Historian continues the history of immigration in Colorado that he began in the pages of our Fall 2020 issue, bringing the story from World War II up to the present.

1904: The Most Corrupt Election in Colorado History Between stuffed ballot boxes, election clerks hopping off trains, and three governors in a day, Devin Flores might just have a point.

A Big, Complex, and Incomplete Story of the Vote In the fall of 2018, I started working on plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. As we mark this occasion on August 26, what I thought would feel like an ending to this work feels like just the beginning.