Story

All Abuzz About Beneficial Bugs

Celebrating Seventy-Five Years of the Palisade Insectary

The best way to stop a bad bug is with a good one.

Every so often we are reminded that, pandemic aside, Mother Nature maintains her usual cycles—the seasons continue to change, wildlife keeps migrating, the plants and trees around us bloom, thrive, and go dormant again. While Coloradans are currently in the midst of a winter dominated by the challenges of a global health crisis, the natural world carries on, preparing for the spring that will soon emerge.

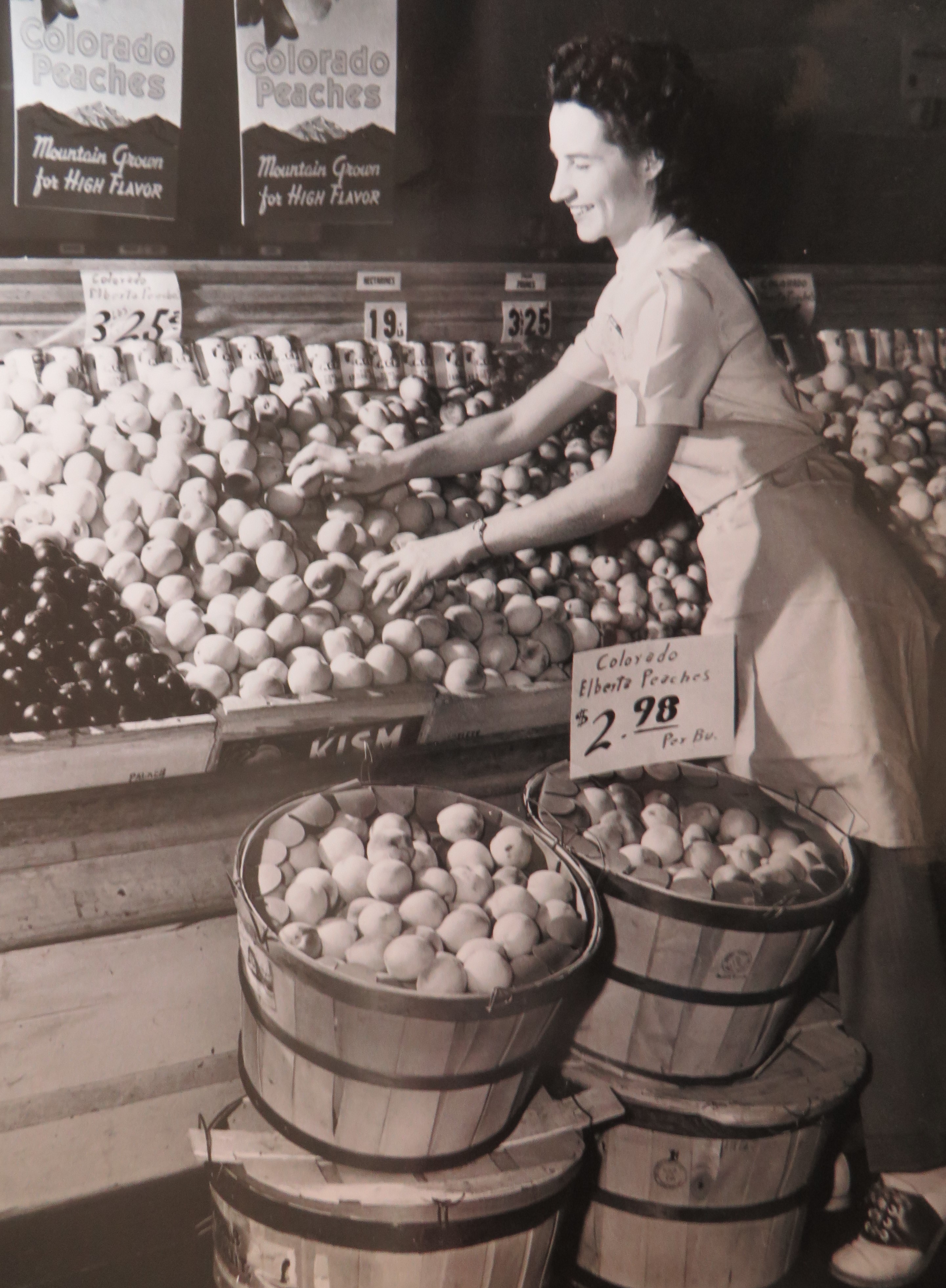

From humble beginnings: the first Insectary, on First Street in Palisade.

At the Palisade Insectary, for the past seventy-five years the Colorado Department of Agriculture has been giving Mother Nature a helping hand. Over decades of developing innovative solutions to keep weeds and insect pests at bay, the scientists at the Insectary continue to help ensure that, despite the tumult that may occasionally beset our communities, we will still have those mouthwatering Palisade peaches to look forward to. And there is very little in this world that doesn’t seem better, at least temporarily, when you bite into a perfect Palisade peach.

Protecting Palisade’s Peaches

When a newly introduced peach pest from Asia began to threaten Colorado’s peach crops back in 1945, farmers turned to a stingless wasp known as Macrocentrus ancylivorus, or “Mac” for short. Mac has the fruit-friendly trait of seeking out and laying its eggs within the larvae of the destructive peach pest called Oriental Fruit Moth (OFM). The eggs hatch and eventually kill the OFM caterpillars from the inside out, earning Mac the title of parasitoid.

Mac became the kind of hero wasp we want to have around, saving delicious Colorado peach crops from OFM decimation ever since. And thanks to Mac, the Palisade Insectary was born.

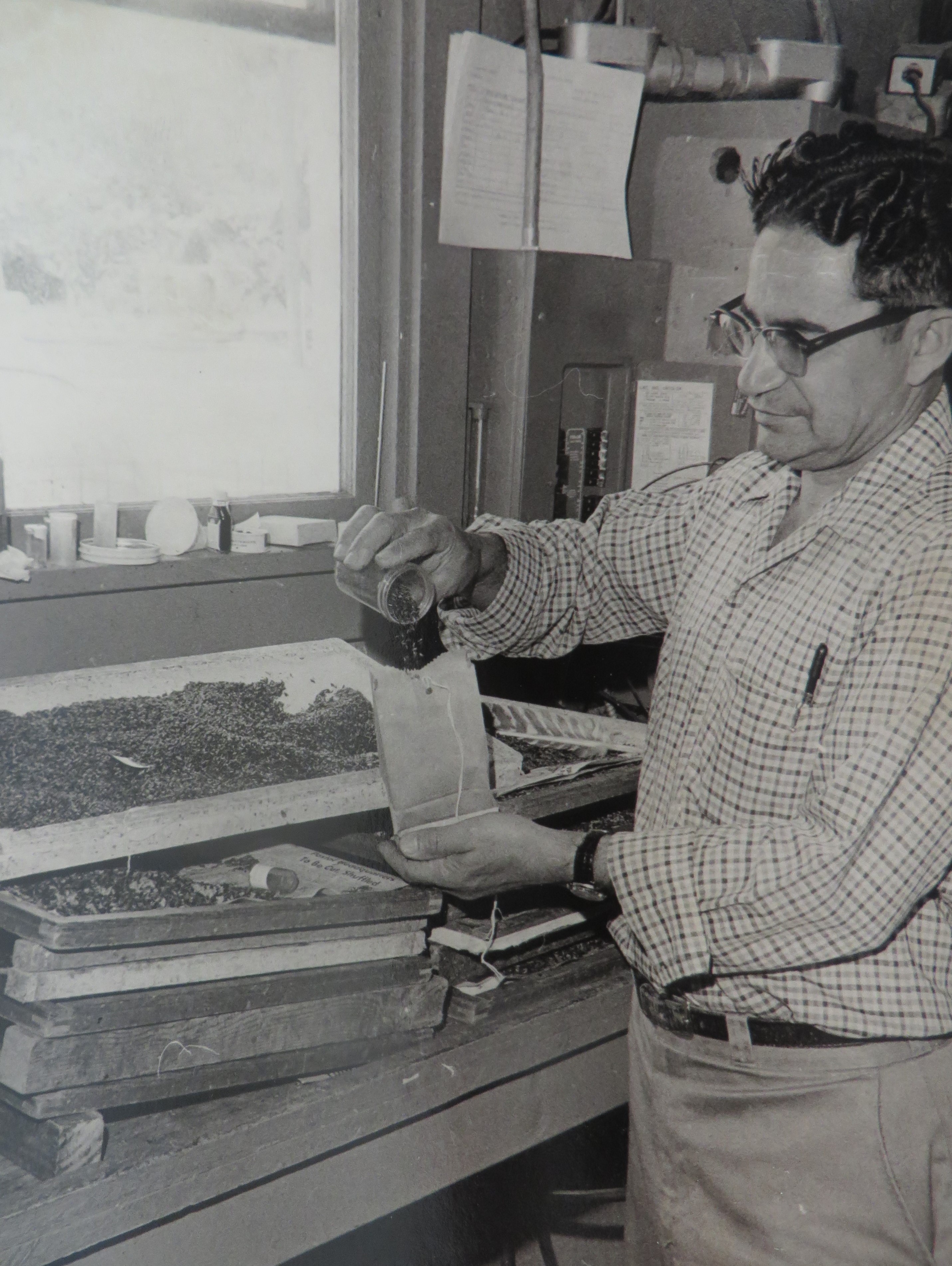

Al Merlino, who was part of the first Insectary crew and later director, measures out Mac pupae.

Since its first job of rearing and releasing Mac into Colorado’s famous Grand Valley fruit orchards, the Palisade Insectary has been assisting Colorado’s farmers, ranchers, and the public with biological insect and weed control for seventy-five years. Today, the Insectary provides farmers with more than two million Mac wasps annually and has added to its collection a long list of biocontrol organisms used to combat other insect pests and weeds throughout Colorado and the West. There are only a few facilities doing this work in the entire United States and, of these, Colorado’s own Palisade Insectary is the oldest.

Why Are Insectaries Important?

An insectary conducts classical biological control, which is the practice of releasing natural insect enemies to bring populations of exotic invasive pest species under control. These pests often cause enormous damage because in new environments, they lack the inherent enemies that would manage them naturally in their homelands. The biocontrol agent populations then continue to grow while controlling the pest species—and once they become well established, the agents rarely have to be reintroduced, providing invaluable protection for crops, trees, and other plant life.

Classical biological control is a careful multi-step process in which natural enemies are determined by scientists in the native lands of the target pest, tested to make certain that they feed on the target and don’t harm native or beneficial species, and are then reared and released against the invasive target species. Pest populations are closely monitored after the release of the insects so that farmers, ranchers, and the public are kept informed as to the efficacy of the release as well as any potential upcoming risks.

Palisade’s Topflight Insectary Team

At the Palisade Insectary, Colorado Department of Agriculture scientists are in regular contact with researchers overseas to learn the status of future biological control organisms and to discuss which weeds and pests are most urgently in need of control in the region. Once a biocontrol agent is ready for release, technicians at the Insectary learn how to propagate it for distribution and set up monitoring sites to measure the impact on the targeted pests. Along with educating farmers, ranchers, and end users about the biocontrol agents, the Insectary staff also keeps the public informed of programs and successes through workshops, information booths, and presentations. Collaboration and partnership is important too—the Insectary works with counties and municipalities as well as federal agencies such as the US Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the National Park Service to distribute these control agents across Colorado.

Tamarisk was used to fight soil erosion on the Great Plains in the 1930s, but has proven over time to be a less desirable ecological partner.

Peachy Results

For the last seventy-five years, the Palisade Insectary has been at the forefront of the development and release of biocontrol agents as they become available in the United States. One particularly noteworthy success has been the partial constraint of the riparian invasive shrub called tamarisk. Tamarisk was introduced from China and Russia as a windbreak tree in the early 1800s and used to fight soil erosion on the Great Plains in the 1930s. The shrub consumes excessive amounts of water, displaces native species, and provides poor habitat and forage for wildlife and livestock. Thanks to the Insectary’s work with the northern tamarisk beetle, tamarisk has decreased by an impressive 50 percent on Colorado’s Western Slope, cutting precious water consumption in half and saving millions of dollars annually.

Tamarisk beetles are shown here being released to do their important work.

In addition, by propagating these hard-working bioagents the Insectary is currently able to combat seventeen invasive weed and pest species, including Emerald ash borer, Japanese beetle, field bindweed, puncturevine, leafy spurge, tamarisk, Dalmatian toadflax, diffuse knapweed, Canada thistle, and Russian knapweed. These supernal insect agents help farmers, ranchers, and other resource managers spend less to inhibit unwanted pests and reduce their use of expensive herbicides and pesticides—which benefits us all.

Together with a network of biocontrol workers and researchers, the Insectary is developing the next round of agents for use against invasive species, and will soon receive a mite that feeds on growing shoot tips of the noxious weed hoary cress. Other goals for future and much needed biocontrol development include tumbleweed, cheatgrass, Russian olive and houndstongue.

Request-a-Bug

For those interested in insect biocontrol, the Palisade Insectary provides these mighty little agents directly to the public through a program called Request-a-Bug. For a small fee to cover shipping costs, members of the public can receive pest control heroes for their own use. The most popular Request-a-Bug insect is the field bindweed mite, most often used by homeowners to combat the ubiquitous field bindweed. The mite feeds on bindweed, causing the leaves to curl up—the vines become stunted and eventually die back, eliminating the need to use toxic herbicides.

Plan a Visit

The Insectary is often crawling with members of the public keenly interested in agriculture and pest control, as well as students of all ages who are studying agriculture, entomology, botany, or natural resources management. Tours are offered to as many as fifty groups annually, highlighting the value of agriculture to Colorado and the need for natural sustainable pest control options. For more information, visitors are advised to contact the Palisade Insectary at 970-464-7916 or insectary@state.co.us in advance to ask about tour availability. The Palisade Insectary also hosts an educational booth at the Palisade International Honeybee Festival every year.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Lifting Up History in a Historic Year The 2020 Miles and Bancroft Awards

Among the Eternal Snows Naturalist Edwin James and His 1820 Ascent of Pikes Peak

Historic Hardware May Help Fight COVID-19 As a preservationist working from home in a 1930s Art Deco apartment building, I have often lamented the fact that so much historic door hardware has been painted over, forever dulling the lovely details that add character and art to our everyday lives. I don’t consider myself an artistic person, so my interest in these seemingly basic details relates to my appreciation of what seems like unattainable creativity on my part.