Story

What the Strikers Were Fighting For

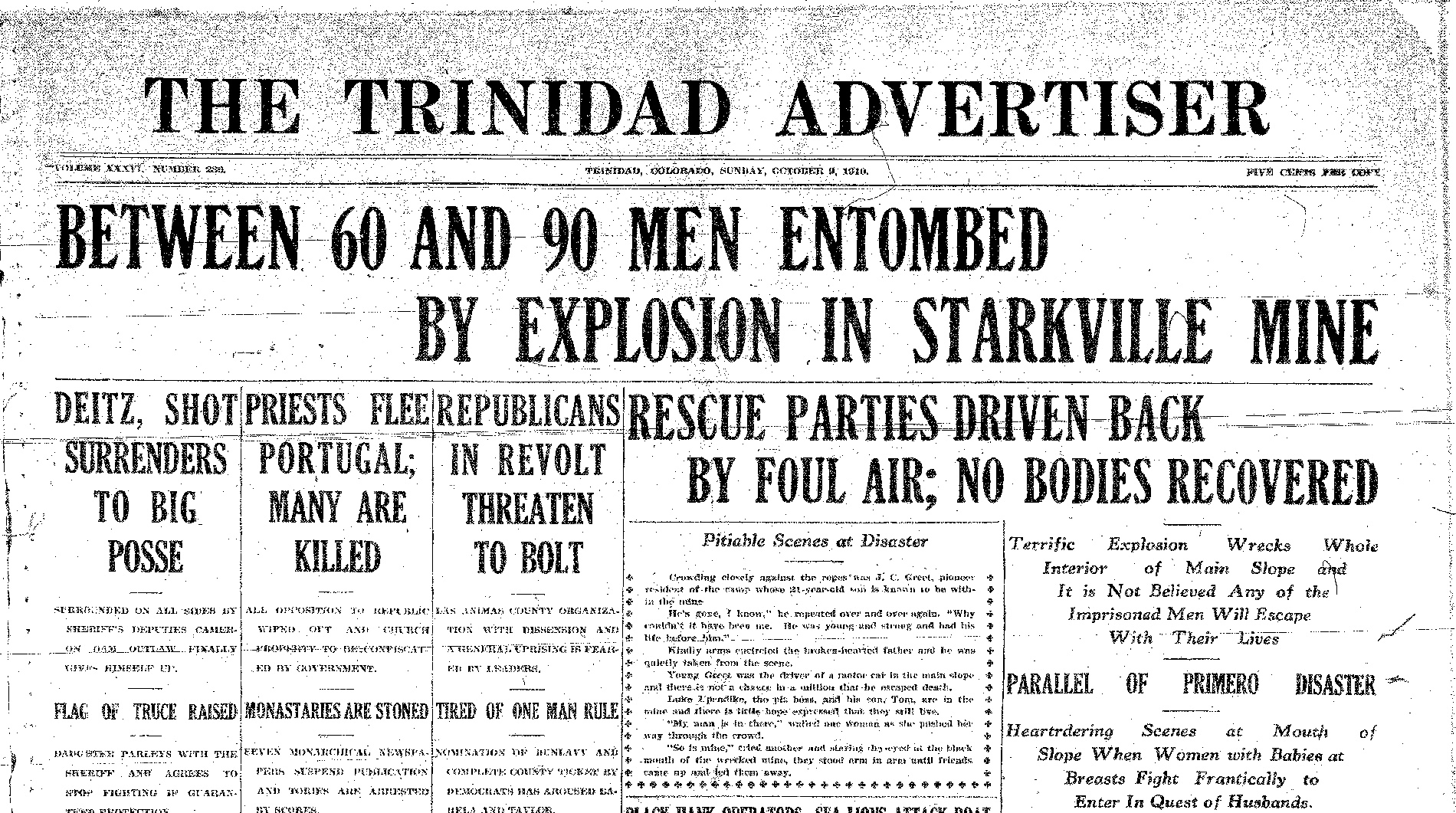

The Las Animas County Coal-Mine Disasters of 1910 and the Great Coalfield War

In this article from the spring 2014 issue of the magazine, Thomas Andrews recounts the horrors and string of failures leading to coal mine disasters in Las Animas County in 1910.

On January 31, 1910, Las Animas County’s Primero coal mine exploded for the second time in three years. Seventy-seven men and adolescent boys were working underground when a “ball of flame” erupted from the mine’s mouth. No one could have known it at the time, but before the year was over, two more explosions would blast through southern Colorado’s coalfields. Starkville exploded in October, killing fifty-six, followed in November by the deaths of seventy-nine more mine workers at Delagua. Never before in world history had three mines lying in such close proximity exploded in such short succession and with such devastating consequences. This unprecedented string of disasters convulsed the hardscrabble camps of the most productive collieries anywhere in the American West. No less important, the 1910 mine explosions intensified longstanding social unrest in Las Animas County. The deaths of more than 200 men in 1910 not only contributed to the outbreak of the Great Colorado Coalfield War of 1913–14, but also help us understand why the strike became the most violent labor conflict in U.S. history.

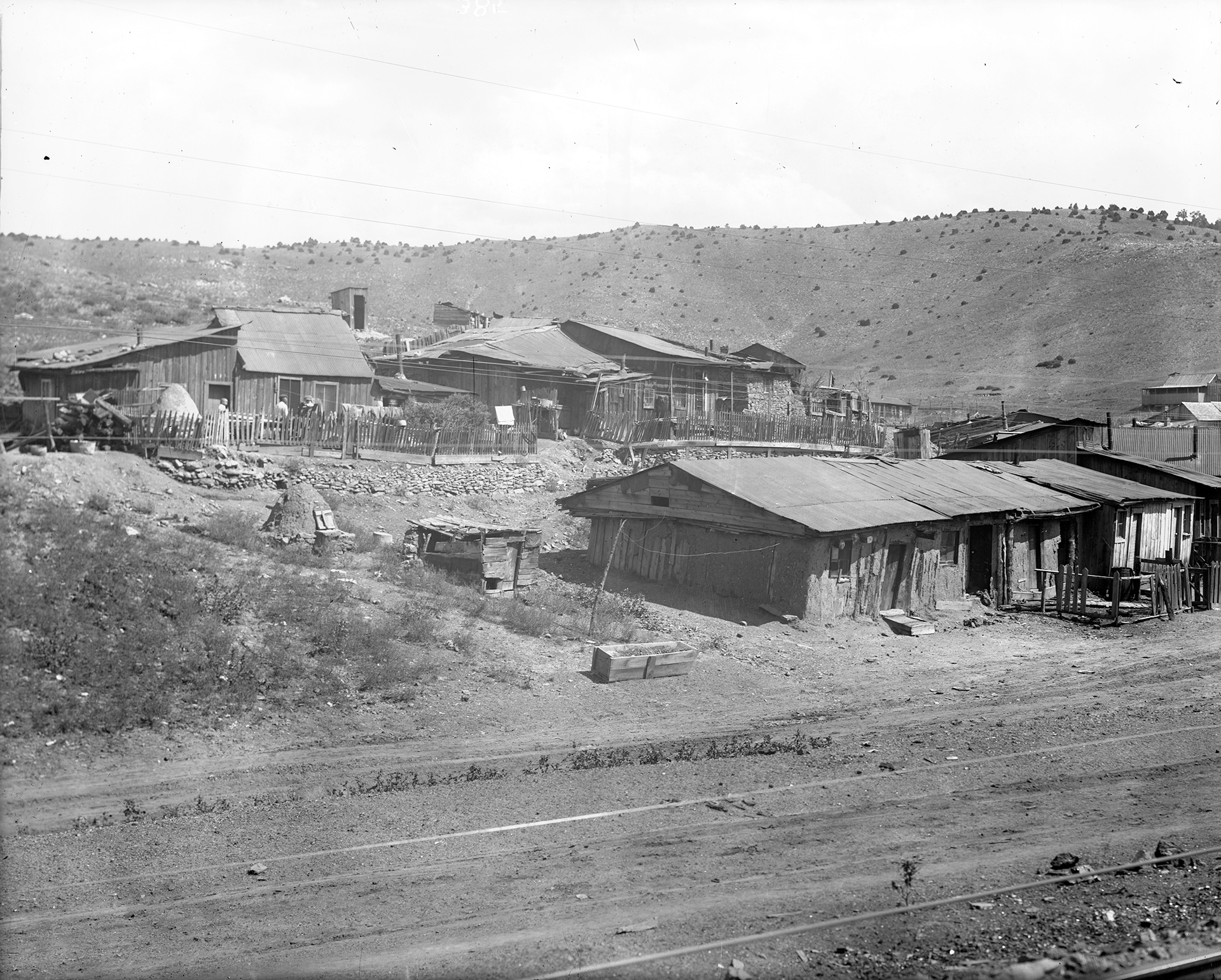

The Colorado coalfields figured among the most dangerous workplaces in the nation, with a fatality rate roughly double the national average for the 1884–1912 period. Highly explosive methane permeated coal deposits in southern Colorado. Worse, the region’s famously dry air increased the risk of dust explosions while also making it more difficult and costly to mitigate dust hazards by sprinkling mines with water. CF&I and its competitors, however, also did much to exacerbate the inherent risks of mining Colorado coal. Mine operators skimped on sprinkling, employed large numbers of inexperienced workers who lacked the skills or knowledge needed to avoid on-the-job perils, blocked the passage of stricter safety laws, and manipulated local politics and court systems in Las Animas and Huerfano Counties.

Rescuers prepare to descend into the mine at Primero. Photo by Trinidad photographer Almeron Newman.

The blast that shook Primero in January 1910 brought an instant response from community members. Off-duty miners and the relatives of those caught underground rushed frantically toward the mine opening. But with smoke and even flame belching out of the tunnel, they could do little but wait until the inferno subsided. Finally, the air cleared and “volunteer rescuers dashed” underground. The “half-crazed wives [who] followed” rescuers into the devastated mine found “portions of human bodies in the debris,” wrote The Denver Post. The desperate women “threw themselves on” these shattered remains, trying “to ascertain if they belonged to their missing loved ones.”

Company officials and local law enforcement feared that the tragedy would unleash disorder and militancy. To keep the peace, two National Guard officers, the sheriffs of Las Animas County and Huerfano County, and several deputies hastily boarded trains to Primero. “As gently as possible,” the Post explained, “the women and children were pressed back” behind ropes. Rescuers then donned breathing apparatus supplied by CF&I’s rescue car and plunged into the shattered mine workings.

Mourners bury five Hungarian miners at Trinidad’s Catholic cemetery following the Primero disaster in January 1910.

These so-called helmet crews found just one survivor: Leonardo Virgen, “a young Mexican, who came here recently from the sister republic,” buried beneath “a heap of a dozen dead men and half as many dead mules.” When rescuers shone a flashlight on his face, Virgen’s “eyes suddenly opened.” He “sat up,” “blinked his eyes and quavered: ‘Please, boss, can I go home now?’” The rescuers carried Virgen out, placing him “safely outside the chamber of the dead.” Not a single one of his comrades would survive.

Mining soon resumed at Primero. Indeed, just a little more than a week after the explosion, the Denver Republican contended that “the disaster is fast being forgotten in the maelstrom of the day’s activities.” CF&I and its employees had money to make, and the people of the West needed coal to burn.

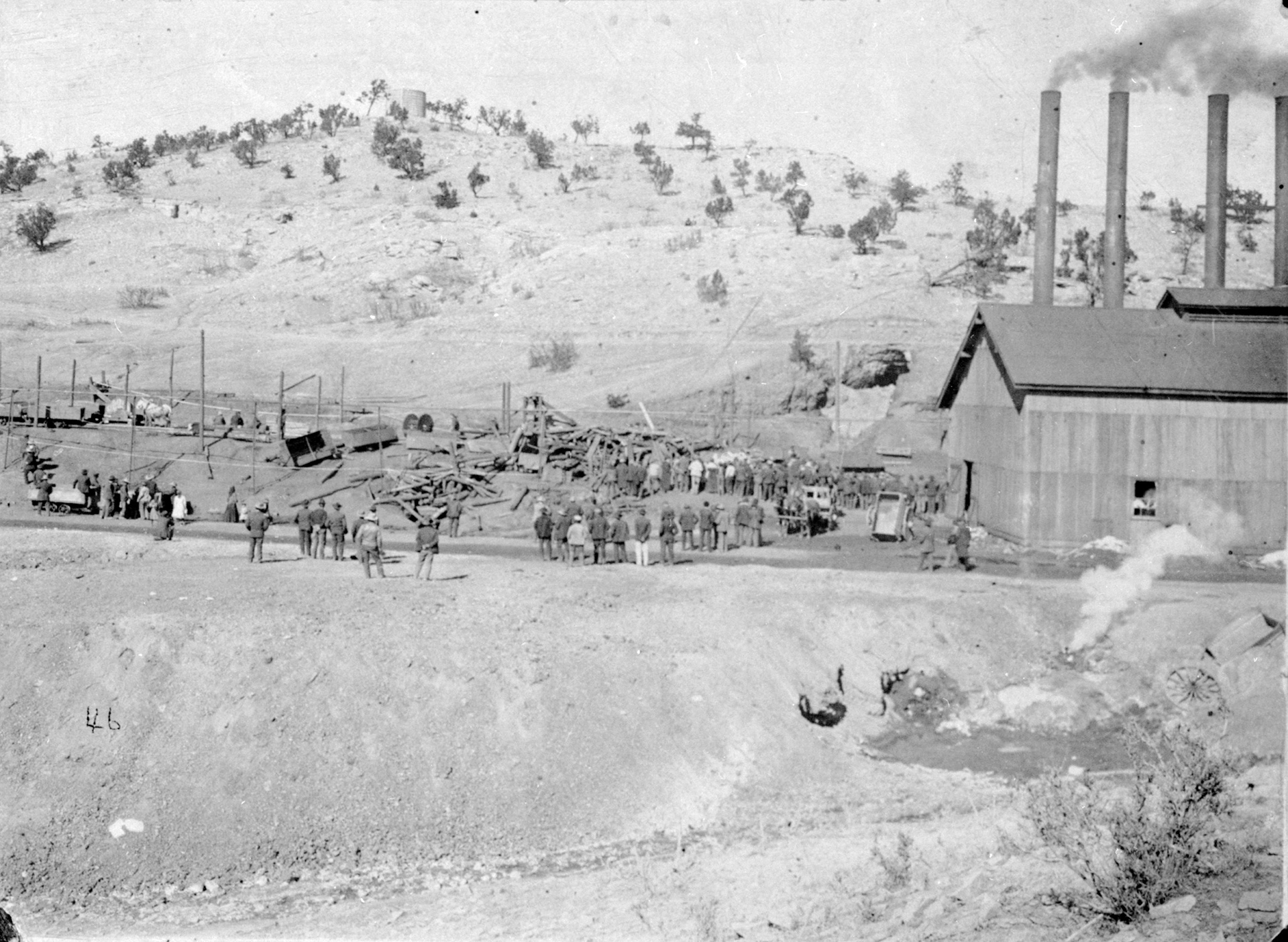

Nine months later, on the evening of October 8, fifty-six members of Starkville’s night shift were caught underground when the mine erupted “without warning.” “Huge rocks and boulders were blown . . . hundreds of feet” at the mine, while the earth shook in Trinidad, five miles away. The “whole” mine was “wrecked” and its ventilation system decimated, both the Post and the Trinidad Advertiser wrote. Vast spans of roof had fallen along the mine’s main tunnels, entombing roughly forty mine workers who had survived the initial detonation “like rats in a trap.”

As the workers trapped underground searched desperately for an escape route, news of the disaster spread quickly. Within minutes, “heartrending scenes” were unfolding outside the mine entrance. “Women, clasping babies to their breasts, rushed frantically to the spot beseeching, demanding some news of their husbands.” CF&I officials implored the wives of night-shift workers to return home, but “not a woman would consent to leave.” As at Primero, the company dispatched “a special force of deputy sheriffs” to establish “strict guard” and “prevent disorder of any character.”

Rescuers formed themselves into crews, then shoved forward with the “feverish intensity of madmen,” risking their own lives to save their fellow miners and “surmounting difficulties,” as the Advertiser phrased it, “which would have made the heart of less strong men quall [sic].” Alas, each sally into the mine brought more bad news about the horrible conditions underground. “Only the most persistent optimist,” the Post noted, “can contemplate the awful devastation wrought by Saturday night’s catastrophe and expect to see a single one of those ill-fated miners emerge from his prison alive.”

Indeed, not a single member of the night shift survived. To compound the tragedy, one rescuer—Fred Foster, “fatigued to the verge of exhaustion from 22 hours’ incessant toil in an effort to reach the bodies of the entombed victims”—fell asleep on a nearby railroad track. As a funeral procession for five Polish workers killed in the blast looked on, Foster’s body was cut in two by a passing coke car. “In any place not already sated with horrors,” a writer for the Denver Post remarked, “such a thrilling conjunction of tragedies would have created tremendous excitement. Yet here, where death has become a familiar sight, no one uttered a sound.”

As crews completed the grim work of removing Starkville’s dead, critics assailed CF&I’s poor safety record. “The charge of neglect,” the Post noted, “is being freely made by men who worked in the mine” and were familiar with conditions within. Newspapers blasted the company for skimping on sprinkling, while anonymous authorities claimed the company had elected a few years earlier not to sink a new tunnel at Starkville. “It is now established,” the Post scolded, “that the Starkville disaster could have been averted had the CF&I expended $10,000 for an air and escape shaft.”

CF&I managers replied that their firm always took all reasonable precautions since mine explosions saddled their balance sheet with a “dead loss”: “all our bookkeeping entries from now on for months,” one noted, “will be set down in red ink.” “The very fact that the explosion occurred,” CF&I attorney Fred Herrington reasoned with breathless cynicism, “proves that the air in our mine was fresh. Fire, you know, feeds on oxygen. I want you to quote me on this.”

A crowd at Delagua surrounds the opening of that coal camp’s mine after the November 1910 explosion.

Disaster struck Las Animas County again in early November. More than 150 men were at work at Victor-American Coal and Coke Company’s Delagua No. 3 Mine when an underground fire detonated coal dust thrust into the mine atmosphere by a passing mine locomotive. When the blast reached the mine mouth, a “tongue of flame leaped” forth and spewed “flying rocks and timbers” into a group of workmen, killing three and injuring five. “It seemed like the lid had blown right off the bottomless pit,” one miner told the Trinidad Chronicle-News, “and all the fires of hell had broken into that mine.”

Several hours later, CF&I rescuers found four men who had successfully maintained a pocket of breathable air by erecting a canvas barrier. Willis Evans, a young Colorado School of Mines graduate who had joined in the rescue effort, gave his helmet “to one of these men who was partly overcome.” Carbon monoxide produced by the explosion soon bore down on Evans. He fell behind the rest of the party as they made their way out of the mine. By the time Evans’s comrades doubled back to get him, the young man was “in practically a state of coma.” He died the next morning. Thanks to the tireless work of other rescuers and the speed with which managers and workers restored ventilation to the mine, eighty-eight men survived, all of whom were working in a district of the sprawling mine left practically untouched by the explosion.

On the second day of rescue efforts, the Chronicle-News portrayed Delagua as a paragon of harmony and cooperation: “every employe[e],” the newspaper approvingly noted, “displayed his loyalty to the company.” Two days later, though, even the Chronicle-News had to acknowledge that “terror” was spreading “among the mine workers throughout the entire southern field.” In the face of mounting discontent, the mine operator, Victor-American Fuel, tried to cajole immigrant employees to undertake the horrid work of recovering the dead from their underground tombs. But no “foreigner” was willing to venture into underground spaces filled with debris, pockets of deadly afterdamp, and the stench of rotting flesh. The company next compelled some of its African American employees to undertake the gruesome task. It took just one day of scraping up bodies and body parts from the fetid mine for the African American “laborers pressed into service to take the bodies out of the mine” to declare a strike. “They would no longer work for $2.95 a day,” they told the company, in dangerous places where “the stench from dead mules and from the bodies themselves was overpowering.” Mexican mine workers, for their part, proved similarly “averse to working until after the bodies are buried,” leaving just “a small force of intrepid men” to bring out Delagua’s dead.

In late November, the coroner’s inquest held over Starkville’s dead delivered a stunning rebuke to southern Colorado’s mighty mine operators. CF&I consul Fred Herrington had told jurors that the explosion had “established a hitherto unrecorded fact in mining science, that under certain conditions dust may explode without the contributing agencies of gas or fire.” Far from an “unrecorded fact,” however, the volatility of coal dust was widely recognized. As the Chronicle-News reported, “All of the witnesses” called on the inquest’s second day, including CF&I’s own mine inspector, “declared themselves convinced that a dust explosion [could] occur without the contributing agencies of gas and fire.” George Rice of the U.S. Geological Survey aptly summarized current thinking in an article in Mines and Minerals: “It is now exceptional to find a mining man who does not accept the evidence of the explosibility of coal dust.”

For years, CF&I had asserted a remarkable degree of control over most every aspect of life in the southern Colorado coalfields. “Even in Russia,” one union miner complained, there was “more liberty as in Southern Colorado.” Company leaders had grown accustomed to determining what counted as “fact” in the region. Yet coal dust failed to heed the specious assertions of CF&I officials. As for the coroner’s jury, it found CF&I guilty of gross negligence. Had the mine “been properly sprinkled,” jurors asserted, the disaster “would not, and could not have occurred.”

The jury’s decision lacked teeth. A few weeks later, another inquest exonerated Victor-American for the Delagua disaster. Even so, most coalfield residents continued to blame mine operators for all three of the 1910 disasters. Support soon swelled behind two broad and overlapping movements to safeguard the lives of miners: safety reform and unionization.

Coal companies willingly embraced some reforms. CF&I pumped resources into training rescue crews, for example, while Victor-American experimented with rock dusting, a novel dust-mitigation technique well suited to Colorado’s dry climate. Few observers, however, trusted the state’s coal companies to change their ways in the absence of state intervention. A Denver Post editorial used the concurrence of the Delagua disaster with election day to push for stronger state regulations on the mining industry. Incoming lawmakers, Post editors declared, “were selected to put statutes on the books that would protect the people of the state—all the people—the people who use the result of the miner’s toil, the man who owns the mine, the endangered digger in that mine. Let those newly elected legislators act!”

Governor Shafroth responded to the public outcry by appointing a special commission to investigate the causes of the 1910 disasters and draft new mine safety legislation. Yet the tragedies in Las Animas County soon faded from the headlines. Mine operators capitalized on growing apathy to block even the modest safety measures proposed by the governor’s commission. It was not until 1913 that the legislature enacted a more agreeable bill drafted by coal companies, state mine inspector Dalrymple, and United Mine Workers of America official John Lawson. But just months after the new law went into effect, the UMWA launched a massive strike against CF&I and other southern Colorado mine operators. One of the strike demands accused the coal companies of refusing to obey even this watered-down law.

The coal mines of Las Animas County had long served as venues for toil, terror, and solidarity; they also became sites of social memory. For mine workers—and many other Coloradans, too—bitter memories of the Primero, Starkville, and Delagua disasters epitomized the failure of mine operators to fulfill their legal and moral obligations to the men who supplied the West’s homes, industries, railroads, and power plants with fuel. In 1910, Robert Uhlich, a tireless union advocate, issued a prophetic warning: “There may be bloodshed on[e] day in Southern Colorado.” Because of “accidents” large and small, the miners were “aroused against this System which exist[s] here.” Uhlich still believed that “we”—he and his fellow union leaders—“could prevent a class war but on[e] Day, we will lose control over the miners, and when this [sic] unorganized go on Strike, it will be a terrible lession [sic].”

As Uhlich sensed, the 1910 disasters would go on to shape not only why miners fought when the simmering tensions in southern Colorado erupted into open struggle, but also how they would fight. The string of tragedies that erupted at Primero, Starkville, and Delagua exemplified the shocking cheapness of human life in coal country. And so in the wake of the Ludlow massacre, which claimed the lives of seventeen strikers in April 1914, battalions of striker-soldiers showed their opponents no quarter, killing more than thirty mine guards, strikebreakers, and state militiamen in ten days of fierce guerrilla warfare. Burning company towns and dynamiting mine tunnels, rebellious workers took aim at the subterranean workplaces in which their relatives, countrymen, and comrades had toiled, suffered, and all too frequently perished.

For Further Reading

Most of this essay draws on local newspapers and Colorado government documents. For more on mine safety in Colorado, see James Whiteside, Regulating Danger: The Struggle for Mine Safety in the Rocky Mountain Coal Industry (University of Nebraska Press, 1990). On underground mine environments as crucibles of labor struggle, see the author’s Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Harvard University Press, 2008). For a more detailed and fully sourced interpretation of the 1910 disasters, see the author’s “Dust to Dust: Colorado’s Coal Mine Explosions of 1910,” in George Vrtis and J. R. McNeill, eds., Mining North America: Environmental History, 1512–2012 (University of California Press, under review).

From the History Colorado Bookshop

Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War, Tom G. Andrews

Coal People: Life in Southern Colorado's Company Towns, 1890-1930, Rick J. Clyne

Making an American Workforce: The Rockefellers and the Legacy of Ludlow, Fawn-Amber Montoya, ed.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Dr. Richard Corwin and Colorado’s Changing Racial Divide As many communities around Colorado reexamine how our public buildings and places are named, we take a look at one man who left his mark on Pueblo. Richard Corwin was an advocate for eugenics and an outsized personality with one of the state’s largest employers.

Hindsight 20/20 The Colorado Magazine asked twenty of today's most insightful historians and thought leaders to share their visions of how 2020 will go down in history.