Story

Pioneer, Indian, Cowboy, Rabbi

Jewish Summer Camping in Colorado

Generations of Jewish Coloradans have spent summer days at Camp Shwayder and the JCC Ranch Camp. Colorado’s mountains have provided the ideal setting for distinctly western Jewish American experiences. Ariel Schnee examines this lesser-known side of Jewish identity in Colorado.

In the early 2000s, I spent a memorable few weeks at Camp Shwayder in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. I started the camp a deeply skeptical and self-identified loner, more interested in books than bonding. But after spending my days hiking, zip lining, and meeting other Jewish kids from around the state, by the end of camp I had fun and even (somewhat grudgingly) absorbed a little of the legendary “Shwayder Magic.”

My adventure in the woods was a small link in a longstanding Jewish American relationship with organized camping. Jewish organized camping arose from many of the same historical trends as American camping at large: progressivism, anxiety about rapid urbanization, and belief in the patriotic, moral, and spiritual benefits of American wilderness. Over time, it assimilated many of the idioms of American organized camping while adapting them to meet changing Jewish cultural needs. As historian Jenna Weissman-Joselit points out, this ongoing dialogue between cultures made Jewish camping a hybrid cultural phenomenon. However, Jewish camps in Colorado understood their cultural roots as not only Jewish American, but also western. At camp, Jews engaged with Colorado’s mountain environments, as well as with western history, myth, and iconography, creating distinctly western Jewish American experiences and identities.

Jewish organized camping began on the East Coast in the late nineteenth century. Not coincidentally, these decades were also the heydays of the early Progressive era: the time of settlement houses, the Chautauqua and “fresh air” movements, and a wealth of other pushes for social reform that engaged issues from public health to temperance. It was also a high point for American immigration, and recent immigrants were the focus of a great deal of Progressive attention. Within American Jewish communities, wealthier, better-established, often Western European Jewish Progressives pursued a range of efforts to support and assimilate largely Eastern European Jewish immigrants who had recently arrived in the United States. Organized camping was a part of that agenda.

Jewish progressives recognized organized camping as a powerful engine for cultural change. American Progressives, Jewish and not, associated camping with education, self-improvement, and the development of American cultural values. Begun in 1893 by the Jewish Working Girls’ Vacation Society of New York, Camp Lehman was likely the first organized Jewish camp. It offered young Jewish women a chance to escape the city’s tenements and factories and take inexpensive trips to the seaside. Jewish summer camps, developed by charitable and communal organizations as well as by private businesses, proliferated throughout New York state, New Jersey, Maine, and elsewhere along the East Coast.

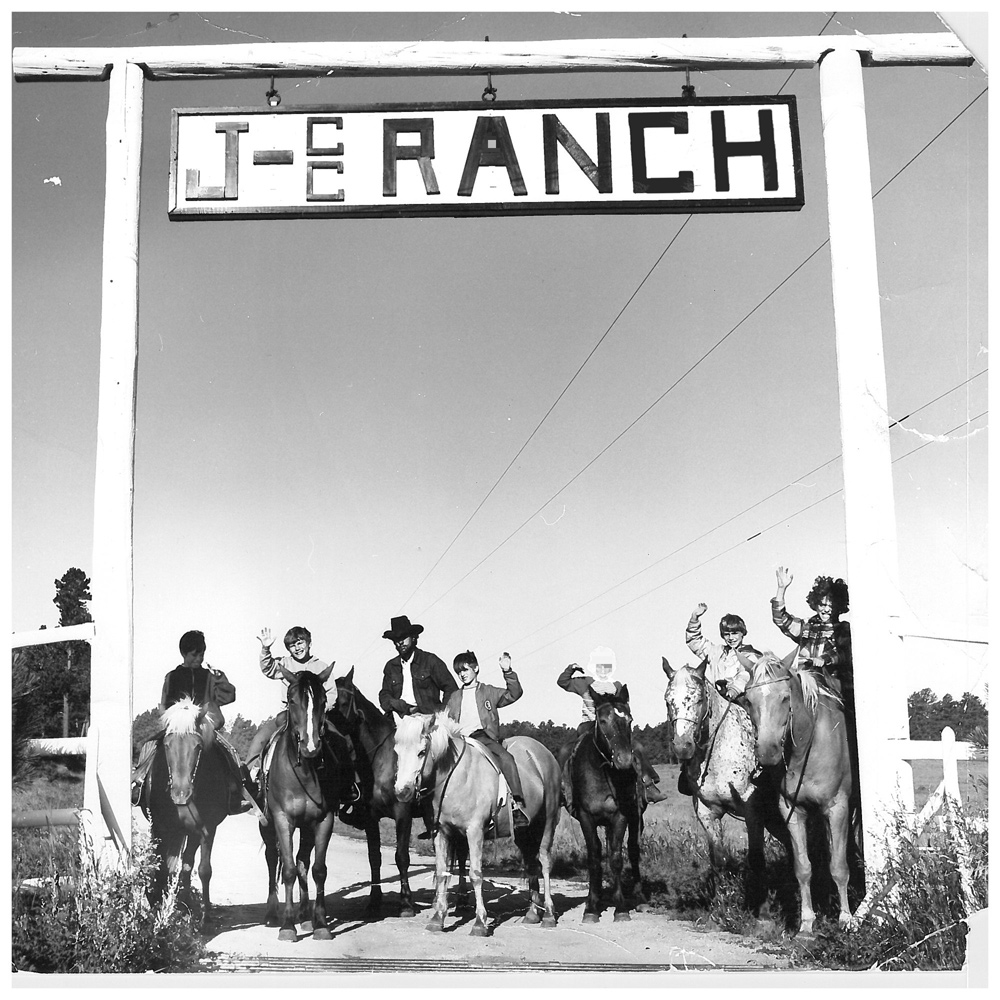

Campers at the front gates of the JCC Ranch Camp which, over time, has expanded to more than 380 acres of the Black Forest in Elbert County.

By the early decades of the twentieth century, Jewish camps had begun pushing west, popping up across the American Midwest. Meanwhile, Jewish people were migrating westward as well. The Galveston Movement, a Jewish resettlement effort active between 1907–1914, transported around 10,000 Jewish immigrants directly from Europe to the American West. For these immigrants, Galveston, Texas was the gateway to the western frontier. The seemingly random choice of destination was, in fact, calculated; in the urban centers of the East, more established Jewish communities began to be concerned that large numbers of conspicuously foreign Jewish newcomers might imperil their own paths to American assimilation and acceptance. Paradoxically, the Jewish-led Galveston Moment both critiqued and reflected many of the anti-Semitic tropes typically levied against male Jewish immigrants at the time—namely that Jewish men were weak, unhealthy, lazy, and effeminate. To counteract immigrants’ perceived effeminacy, the movement recruited only healthy, skilled, “vigorous” Jewish men under forty and their families and placed them onto the American frontier—the symbolic wellspring of American masculinity—to claim and prove immigrant Jews’ rugged physicality through the American ritual of western conquest.

Interested in learning more about the history of Colorado’s Jewish summer camps? In 2019, University of Colorado Boulder highlighted the history of these meaningful places at the Fourth Biannual Embodied Judaism Symposium, along with an exhibit at CU’s Norlin Library that features archival materials drawn from the University’s Post-Holocaust Judaism collections.

Learn more about the history of Jewish camping in the West, access interviews with the organizers, and watch a recording of the entire symposium here.

Despite these efforts to recast Jewish immigrants into rough and ready frontiersmen, in Colorado, most Jews settled in urban areas. The road to acceptance was rocky. Even within established Jewish populations, such as that in Denver, Jews were openly harassed, threatened, baited, attacked, beaten with iron bars, and even lynched by their fellow citizens. Often, there was little justice for crimes committed against Jews. Jews also faced obstacles that limited their access to the state’s mountain environments. Many organized mountain camps and dude ranches had Christian religious leanings or informally discriminated against Jews and were inaccessible (See “Race and Ranching at Rocky Mountain National Park”). In addition, uncertainty or a lack of access to Kosher food, the threat of rejection or humiliation at the hands of rural populations, and, by 1921, the risk of violence at the hands of Colorado’s viciously anti-Semitic and anti-immigrant Ku Klux Klan, all circumscribed Jews’ freedom to explore their state like other Coloradans. Organized Jewish camping, by contrast, offered a reliable, safe way for Colorado Jews to engage with natural environments.

As Colorado’s Jews weathered discrimination at home, internationally they grappled with the trauma of World War II and the Holocaust. For American Jews, the global upheavals of the 1930s and 1940s shook Jewish culture and tradition to its core, and they changed Jewish camping as well. Postwar, the trauma of genocide lent renewed urgency to longstanding Jewish cultural movements like Zionism, Yiddishism, and Hebraism (the preservation of the Yiddish and Hebrew languages, respectively) and deepened concerns about assimilation, Jewish American identity, and the education of Jewish youth. As Jewish camping developed in Colorado in the late 1940s, it reflected these evolutions in Jewish American intellectual and political life.

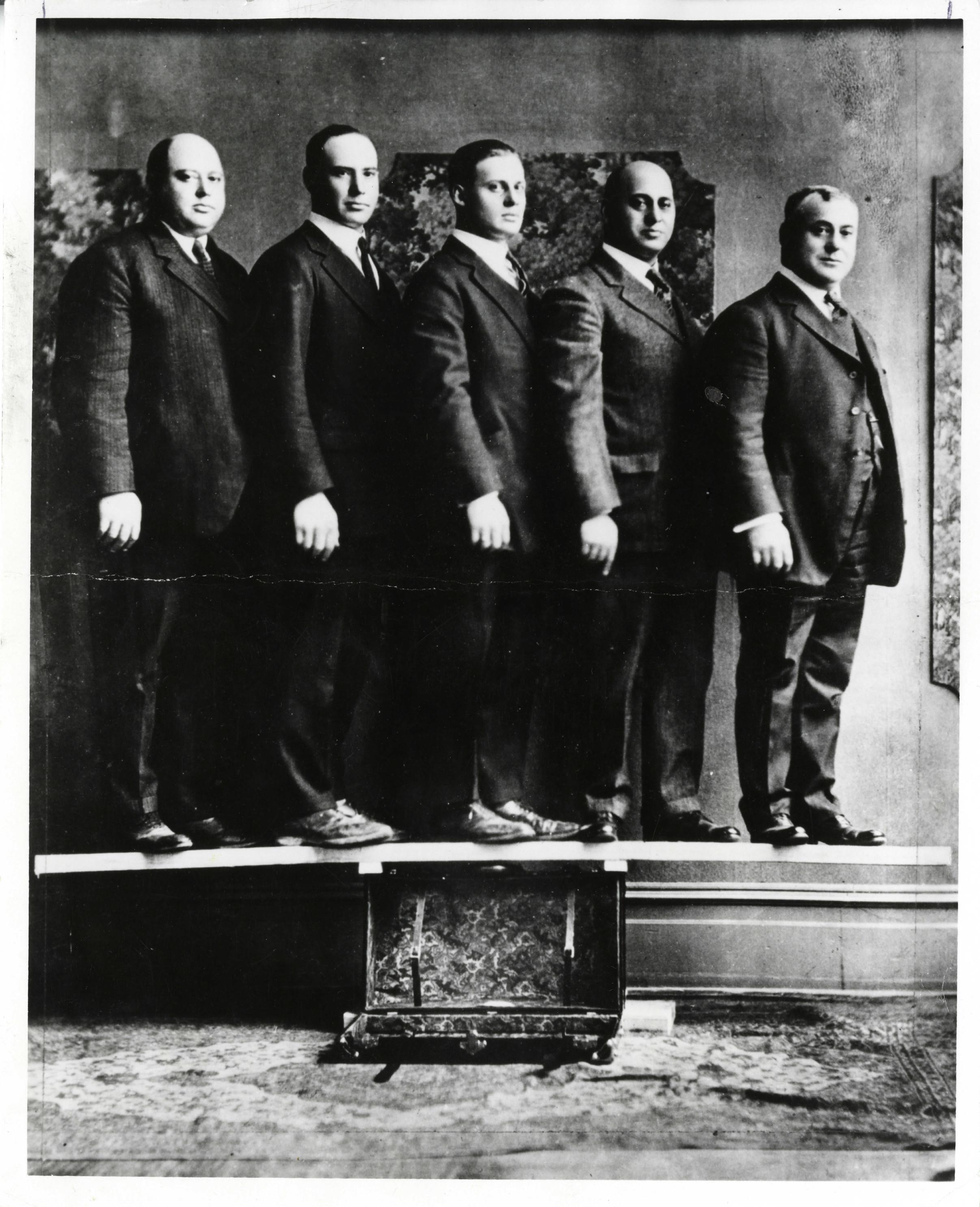

“The Shwayder Brothers Standing on a Samsonite Suitcase.” Pictured here are brothers Mark, Maurice, Benjamin, Jesse, and Solomon, demonstrating the strength of their "Samson" case, around 1910.

Founded in 1949, Camp Shwayder was the first organized Jewish camp in Colorado and the first Reform Jewish camp in the United States. The camp was Maurice B. Shwayder and Ruth Shwayder’s legacy. Maurice’s brother, Jesse Shwayder, was the charismatic leader and founder of the luggage brand Samsonite, previously known as the Shwayder Trunk Manufacturing Company. The five brothers and family patriarch, Isaac Shwayder, were all involved in the business—one of the company’s iconic early advertisements featured the brothers standing on one of their trunks with the tagline “Strong enough to stand on.” The Shwayder family was active in the Denver Jewish community and were well-known local philanthropists. Following Maurice’s death in 1948, Ruth donated the family’s 242-acre fishing retreat in the shadow of Mount Evans to Denver’s Reform Jewish synagogue, Temple Emanuel. Shwayder’s gift illuminated the changes in Jewish camping that had taken place since the 1880s. Rather than being geared towards the acculturation and education of young adults, Camp Shwayder was a children’s camp. There, Jewish youth connected to their Judaism, one another, and to the camp’s mountain environment. Camp activities featured organized sports, a smattering of Jewish education and prayer, hiking, and, by the 1970s and 1980s, more strenuous activities including backpacking, overnight camping trips, and mountain ascents.

As a Reform Jewish camp, Camp Shwayder was never intended to meet Colorado’s entire Jewish community’s need for access to organized camping. It did not observe Kosher dietary restrictions and did not maintain a Kosher kitchen, which prevented children from orthodox and conservative households from attending camp. It also reflected the class dynamics of the larger Jewish community in Denver. The Reform Jewish community tended to be wealthier, and the conservative and orthodox Jewish communities less so. As a result, another kind of Jewish camping emerged to fill the gap.

JCC Ranch Camp, supported by the Staenberg-Loup Jewish Community Center (JCC Denver), primarily served orthodox and conservative Jewish populations. Located on 175 acres of the Black Forest near Elbert, Colorado, the camp developed on the site of a historic ranch. Known both as The Ten Sleep Ranch and the Hubbard Ranch, the land was once owned by Ralph Hubbard, a well-known historical enthusiast and western collector. The land had been a working cattle ranch since at least 1916. After Hubbard sold the ranch, it passed through several hands and, according to camp lore, shifted from working ranch to dude or guest ranch. In 1952, JCC Denver acquired the land for $15,000, as well as several of the historic log and stone buildings that had comprised the Hubbard Ranch’s original facilities. Money raised from a wide range of Jewish foundations, businesses, and private donors went toward outfitting the camp, building cabins, and improving facilities for its first season in 1953.

"The JCC director who acquired the ranch described the camp as 'an unusual project which combines an American western ranching program with Jewish content and a kosher kitchen.'"

At Ranch Camp, the connection between Judaism and Western Americana was apparent—the camp even sold a grazing lease to N.W. Cook of Elbert, Colorado for thirty head of cattle. Described by one of the camp’s founders, JCC Executive Director Arnold J. Auerbach, as “an unusual project which combines an American western ranching program with Jewish content and a Kosher kitchen,” the camp consciously blended western experiences with Jewish education and culture. Originally, the camp’s founders envisioned campers participating in many of the activities involved in operating a working ranch—growing hay, branding and rounding up cattle, and caring for the ranch’s horses. While only some of these goals were actually realized, many of the activities at Ranch Camp would have been right at home at any other Colorado dude ranch, including horseback riding, pack trips, square dancing, hikes, cook outs, and campfire sing-a-longs.

The “Jewish content” of the camp focused on creating a sense of cultural (rather than exclusively religious) Jewish identity among campers and a spiritual Jewish connection to land that recognized the divine in the natural world. This approach connected campers with specific Jewish figures associated with nature and animals, such as the Jewish mystic, Bal Shem Tov. The camp’s unique environment also created new kinds of Jewish experiences, such as outdoor religious meditation conducted as the ranch’s horses grazed nearby. Other traditions emerged that were unique to Ranch Camp itself. At the end of a session, campers were instructed to rub dirt on their jeans, and never wash them until they returned the next summer, keeping them connected to camp by literally carrying the land home with them. Formal instruction, prayer, shared experiences, and informal rituals were the building blocks of campers’ western Jewish American identity.

Inescapable from Jews’ embrace of their own western identity was the West’s Native American history, both imagined and real. The entanglement between organized camping and Native history was longstanding, but peaked in the 1940s and 1950s. At the time, a broad American fascination with all things western expressed itself at camps nationwide through the appropriation of Native folklore, language, clothing, art and design, tradition, and iconography with varying levels of accuracy and respect—even extending to encouraging campers to imagine themselves as Native Americans or “play Indian” in redface. These tropes were present at Jewish camps as well.

At the JCC Ranch Camp, the land’s Native history was impossible to ignore. Ralph Hubbard claimed that the land had a longstanding connection to Native American history, and artifacts created by Indigenous people had been discovered on the camp’s land. Even as it celebrated western ranch life, the camp’s approach to educating campers about its longer history was relatively sophisticated. According to Dr. Julie Kramer, one of the camp’s former directors, by the 1960s the camp’s curriculum included critical engagement with Native American history, including dispelling myths about Native peoples, differentiating among different tribes associated with the area, and developing relationships with Native people who had connections to the land the camp occupied. While it is difficult to say why the camp’s leadership chose to acknowledge its cultural and historical paradoxes, it is possible that their choice reflected western Jewish Americans’ own complicated experiences of oppression, intergenerational trauma, cultural loss, displacement, and genocide.

While Jewish organized camping originated as a driving force for American cultural assimilation, after World War II the purpose of Jewish camping shifted to the cultivation of Jewish youth. Under the postwar model, Jewish youth developed interpersonal connections and skills intended to make them secure and confident in their Jewish American cultural identity. In Colorado, Jewish organized camps reflected that change, but they also took on a distinctly western flavor, integrating hiking, overnight camping trips, backpacking, horseback riding, and other activities. The camp experience at Camp Shwayder and JCC Ranch Camp alike relied on dependable, permanent access to western landscapes that provided both recreational opportunities and a sense of place—rugged mountain terrain, deep pine forests, and the open sweep of Colorado’s ranchlands. For campers (as well as staff and camp alumni), these places are imbued with community memory, but the land is also connected to Colorado’s wider history. While western Jews did not, in general, turn out to be the rough and tumble pioneers the recruiters of the Galveston Movement had envisioned, ultimately, they still became Westerners.

For further reading

Brief Histories of the Denver Public Schools, Compiled for Denver Public Schools, 1952. Denver Public Library, Western History and Genealogy Collection: Denver, CO.

Camp Shwayder, “About Us.” https://www.shwayder.com/about/.

Deloria, Philip. “Hobby Indians, Authenticity, and Race in Cold War America,” in Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

Fox, Sandra F. “Laboratories of Yiddishkayt”: Postwar Jewish Summer Camps and the Transformation of Yiddishism,” American Jewish History, Vol 103. 3 (July 2019).

Imhoff, Sarah. “Embodied Judaism: Masculinity and the US West,” Lecture. Colorado University at Boulder: Fourth Biannual Embodied Judaism Symposium, Jews Out West. November 2019, Boulder, CO.

Jewish Museum of the American West, “The Shwayder Family: From Back-Pack Peddling to Samsonite Luggage, Denver, Colorado.” April 13, 2014. http://www.jmaw.org/shwayder-jewish-samsonite-denver/.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. “The Jewish Way of Play,” in A Worthy Use of Summer: Jewish Summer Camping in America.

Koffman, David S. “Playing Indian at Jewish Summer Camp: Lessons on Tribalism, Assimilation, and Spirituality, Journal of Jewish Education (2018).

Kramer, Addison and Dr. Julie Kramer. “Western Judaic Experiences: the J-CC Ranch Camp” Lecture. Colorado University at Boulder: Fourth Biannual Embodied Judaism Symposium, Jews Out West. November 2019, Boulder, CO.

Lee, Michael Adam. “The Politics of Antisemitism in Denver, Colorado,” diss. University of Colorado, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1904509596?pq-origsite=summon.

Manaster, Jane. “The Galveston Movement,” Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/galveston-movement.

Sladek, Ron and Tatanka Historical Associates, Inc., J Bar Double C Ranch, Colorado Register of Historic Properties Nomination Form. https://www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2018/5el656.pdf.

Zola, Gary P. “Jewish Camping and Its Relationship to the Organized Camping Movement in America,” A Place of Our Own: The Rise of Reform Jewish Camping, Edited by Michael M. Lorge and Gary P. Zola, (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2006).

More from The Colorado Magazine

“We Will Go Wherever We are Needed and Do Whatever Comes to Hand” the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. Here, a member of the Volunteers of America team recognizes an organization that’s provided more than a century of compassionate aid to communities in need in Colorado and throughout the nation.

All Abuzz About Beneficial Bugs Celebrating Seventy-Five Years of the Palisade Insectary

Health, Recreation, Education, and Uplift: Lincoln Hills and Black Recreation in the Colorado Mountains When temperatures soared in cramped, noisy cities, Colorado’s higher elevations promised chilly nights and mild days spent fishing, camping, and hiking under shady pine trees. Unlike their white counterparts, however, African Americans could not head just anywhere in the mountains. Not far outside of Denver, Lincoln Hills, a vacation community developed for Black people, represented both an escape from the city and an escape from segregation.