Story

The Little World Series of the West

Integrating Baseball in Denver

Black baseball players shaped the game and American society beyond the ballfield. It’s a story that runs, surprisingly, straight through Denver and an event that called itself “The Little World Series of the West.”

It was a warm evening in Denver on August 1, 1934, and the lights were on above Merchants Park on South Broadway as a record crowd waited expectantly in the grandstands. It was the opening day of the annual Denver Post Baseball Tournament, “The Little World Series of the West,” the paper liked to call it. And this was the game everyone had been waiting for.

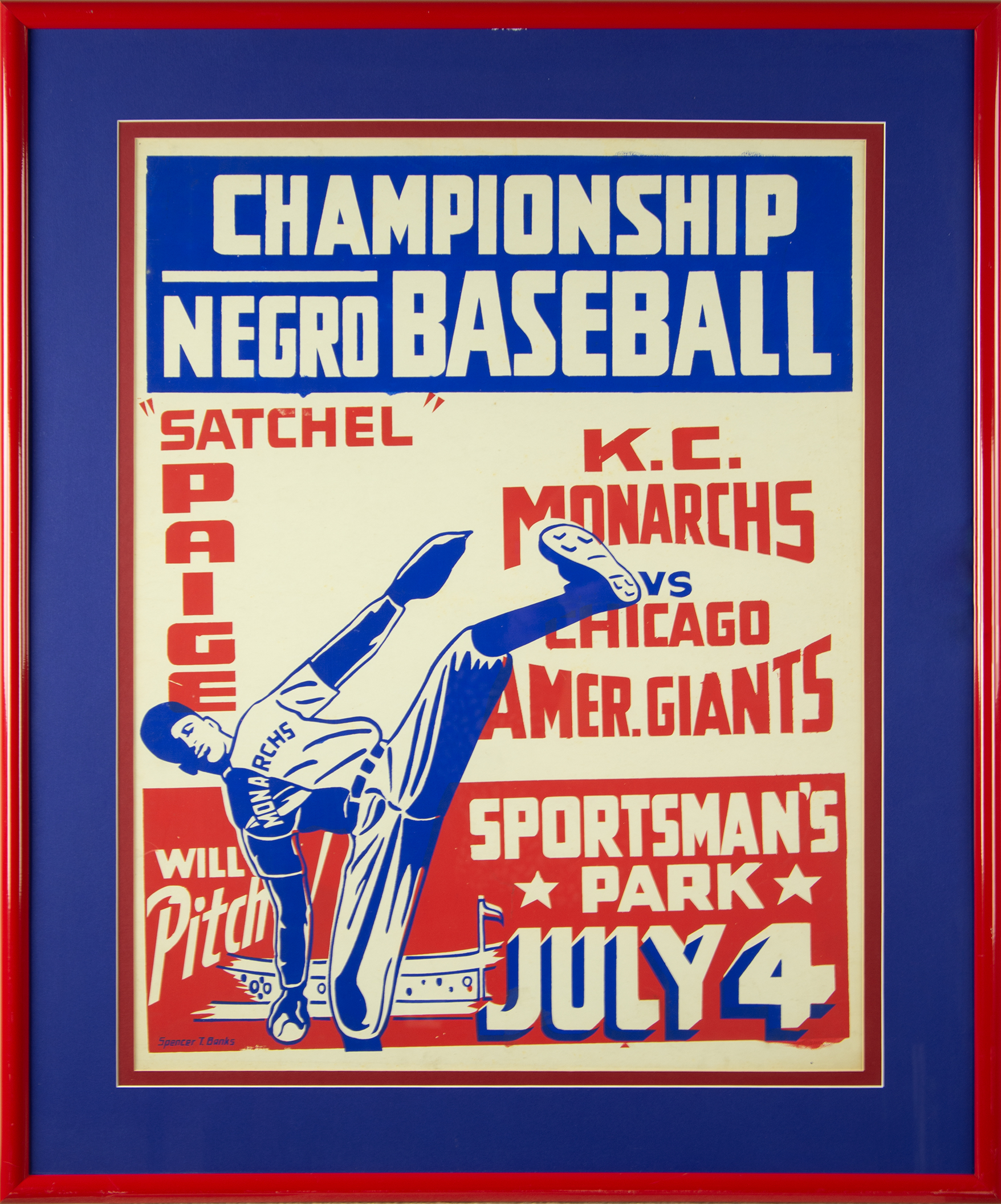

Poss Parsons, sports editor of The Denver Post, had invited the Kansas City Monarchs, champions of the Negro National League, to participate in the tournament that year. The idea was to raise the level of play. This was, after all, supposed to be the Little World Series of the West.

The Post Tournament was celebrating its twentieth anniversary that summer, and it had established a reputation for showcasing some of the best baseball west of St. Louis, which was as far west as the major leagues went at that time. The Post offered enough prize money to attract talented teams from around the country—often with major league ringers added to the lineup for the tournament—to compete in Denver each summer.

The Kansas City Monarchs were the talk of the town when they came to play in the Denver Post Tournament in 1934.

But the games could be even better, and Parsons knew it. So in 1934 he invited the Monarchs, perennially one of the best teams in the Negro Leagues. The Monarchs’ lineup for the tournament featured star players at nearly every position, including Bullet Joe Rogan, Turkey Stearnes, and Willie Foster, all of them in the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame today. And at 8:30 that evening, the Monarchs took the field against a local team from Greeley.

There had been exhibition games and barnstorming games and other informal contests between black and white players for almost as long as baseball had been segregated. But this night in Denver was the first time that players at a professional level played integrated baseball since the color line had been drawn in the late nineteenth century.

It was a remarkable moment in segregated America—much less in a city and state not a decade removed from a government controlled at every level by the Ku Klux Klan. One might’ve expected sparks. Bottles thrown on the field. Threats. Or worse. But Coloradans, on that warm August night, just seemed happy to see good baseball, black or white. And they cheered as the Monarchs walked away with the game, 12 to 1.

Satchel Paige was the biggest draw in the Negro Leagues throughout the 1930s and ‘40s. A dominant pitcher who could headline any marquee matchup, his talent was matched by his charisma and showmanship. One of his most famous gambits was to call his outfielders in at the beginning of an inning and have them sit on the infield dirt while he proceeded to strike out the side—a bit of showmanship he thrilled crowds with during his first appearance in the Denver Post Tournament in 1934.

The Monarchs dominated their competition until the championship series, when they ran into an otherwise all-white team from Michigan that had hired Satchel Paige—then the most famous pitcher in the Negro Leagues, and one of the best pitchers of all time—to be sure it could compete against them. “Paige, one of the outstanding hurlers in the Negro National League, is said to be as fast as anybody in baseball,” noted The Denver Post, adding for good measure, “Yes, that includes the fireball flingers of the big leagues too.” In front of another record-setting crowd, Paige earned his fee in the championship, defeating the Monarchs 2 to 1.

In 1936, Satchel Paige came back to Denver with a hand-picked team of Negro League All-Stars on a quest to win the tournament and its lucrative prize money. The team featured four of the game’s all-time greats: Paige on the mound, Josh Gibson catching, Buck Leonard at first base, and Cool Papa Bell in center field. After their first game, Denver Post baseball writer Leonard Cahn reached for metaphors to describe to his readers how good the team was: “They’re the cream in your coffee, the icing on your cake, the champagne in your cocktail. They’re CLASS! Every man on the team is so outstanding it is hard to single out any players in particular. They all lived up to their reputations.” In the championship game, Paige struck out 18 as the All-Stars cruised to victory. The following year, Satchel Paige returned to repeat the feat once again with many of the same players, establishing the Negro Leaguers’ dominance in the tournament.

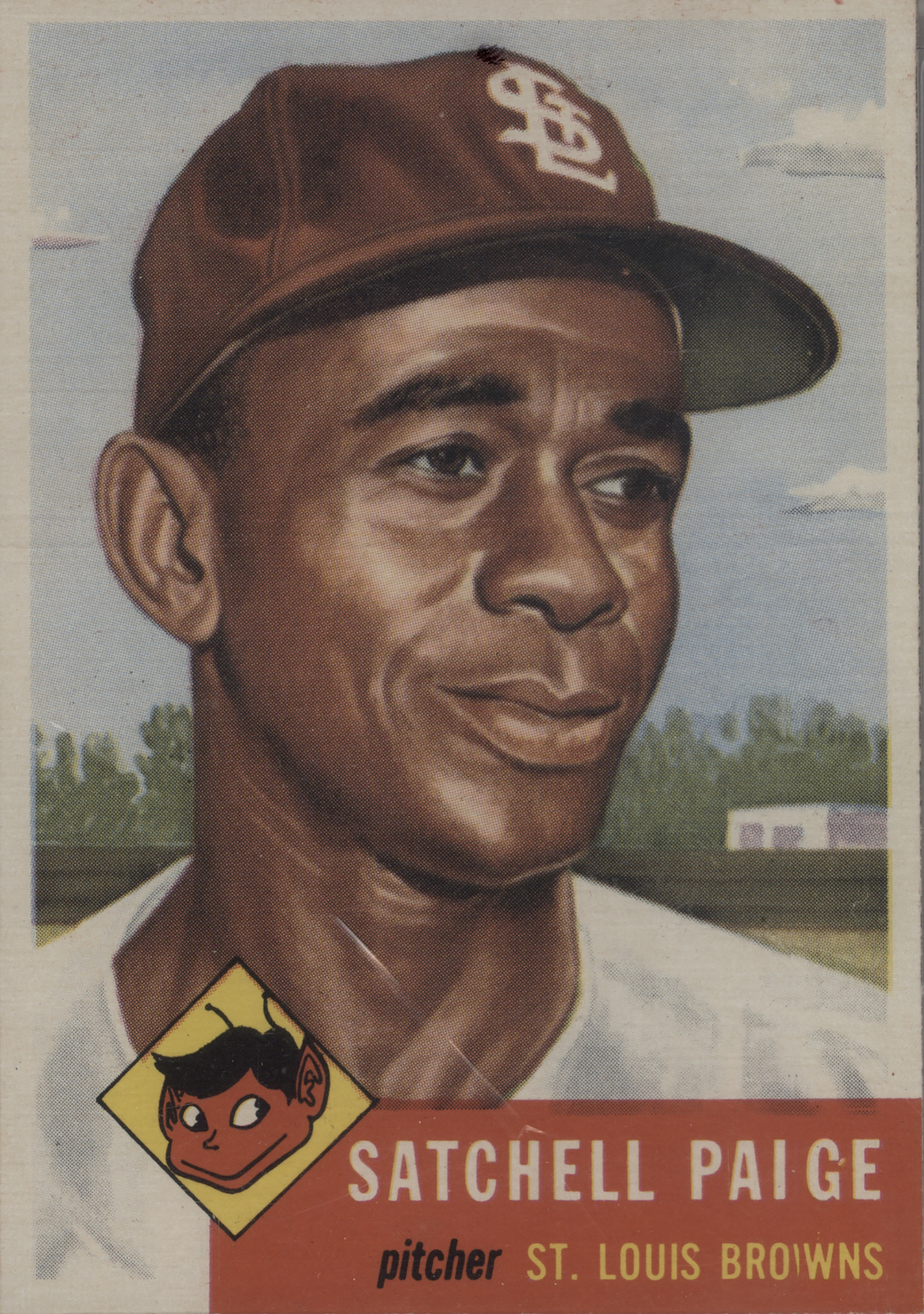

As Major League Baseball integrated its rosters in the late 1940s and ‘50s, Satchel Paige became the oldest “rookie” in big league history. He helped pitch the Indians to the pennant in 1948, and in 1953, now approaching 50 years old, he still had enough juice in his right arm to be selected as an All-Star representing the St. Louis Browns. When the Hall of Fame formed a special committee in 1971 to elect Negro League players, Satchel Paige was the first man they inducted.

Black teams played white teams more than 400 times in off-season exhibition games during the segregated period between the late nineteenth century and Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut in Brooklyn. By most accounts, the African American teams won 60 to 75 percent of those games. But the exhibition nature of the games made it possible for segregation-minded fans and major league executives to dismiss them—and black baseball players—as below the major league standard of play.

The Denver Post Baseball Tournament was harder to dismiss. The lucrative promise of the tournament attracted talented players, many of whom went on to play in the big leagues. The integrated games in Denver during the 1930s were not simply entertaining exhibitions but real competitions, the first between professional black and white players since the major leagues had segregated the game. It was a milestone that made it increasingly difficult for baseball’s racists to claim that black ballplayers couldn’t compete at the highest level. With each story sportswriters wired out from Denver to newspapers around the nation praising the African American players’ skill and talent, the tournament dispelled the notion that the Negro Leagues represented an inferior “shadowball” form of the big league game.

That Denver Post Tournament in 1934 was a pivot point in the long history of African American players in baseball. It’s a history as old as the game itself. A history that in many ways mirrors American history between the Reconstruction period after the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement of the late twentieth century. Black players were shut out of Major League Baseball, organized their own leagues, broke back through the color barrier, and in important ways shaped not just the game, but the American story well beyond the ballfield. It’s a story that runs, surprisingly, straight through Denver and “The Little World Series of the West.”

This article is adapted from Game Changers: 100 Years of Negro League Baseball, published by History Colorado. It first appeared in Rockies Magazine under the title “Game Changers.” History Colorado is proud to partner with the Colorado Rockies to present the Hall of Legends exhibition at McGregor Square during the 2021 All-Star Week.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Left on the Field: Colorado’s Semi-Pro and Amateur Baseball Teams When towns and companies fielded teams, the stakes were never higher nor the competition fiercer.

Waiting for Someone to Listen Rediscovering one of America’s great golf champions.

Imagining a Great City Mayor Federico Peña’s campaign vision to “Imagine a Great City'' catalyzed the development of Denver and its region from the 1980s onward.