Story

Comic Books: The Super Artifacts

Look! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s…a diagnostic artifact! An archaeologist explains how discarded comic books help reveal the history of a place.

Archaeologists are like detectives, trying to understand who was at a site and when. These two questions ("who" and "when") are recurring mysteries that archaeologists ask at every site we discover. Meanwhile, in the year 2021, the earliest comic books have morphed into classical lore. Now, fiction and non-fiction can come together to tell the true stories of our ancestors. Comic books can serve as clues to solving these two perennial questions. But before I can explain how comic books do this, let me give you some back story.

Whenever I play "show and tell" with a cool artifact, people always want to know what it is and who used it. Whether the artifact is a spoon, a stone tool, or piece of ceramic, the same questions always come up. Then, someone always asks me the age of the object. And no sooner have I done my best to answer these questions, when the perfectly logical follow-up question arises: How do I know how old it is? The answer to this last question, it turns out, is always a little complicated.

On the one hand, we have what are called radiometric dating techniques. The most famous of these is loosely called carbon dating: An archaeologist takes a sample of old material and sends it to a laboratory, where chemists measure the ratio of radioactive carbon to stable carbon. That ratio, once ascertained, lets us know how long it has been since the sample died. You see, these samples must come from organic materials that were formerly living, such as decaying plants and animals. Once the organism died and stopped taking in fresh carbon from the environment, it stopped taking in radioactive carbon. The radioactive carbon then decays at a constant rate. Thus, if we find a sample with very little or no radioactive carbon, we know it is much older than a sample with high levels of radioactive carbon.

But testing samples for radioactive carbon (or other radioactive materials that decay more slowly) is expensive and time consuming. Furthermore, only valid samples will yield valid results. Radioactive carbon resides in organic materials. So, an absence of organics, or contamination from modern sources (like burrowing insects), can make it impossible to get a valid sample for radiometric dating.

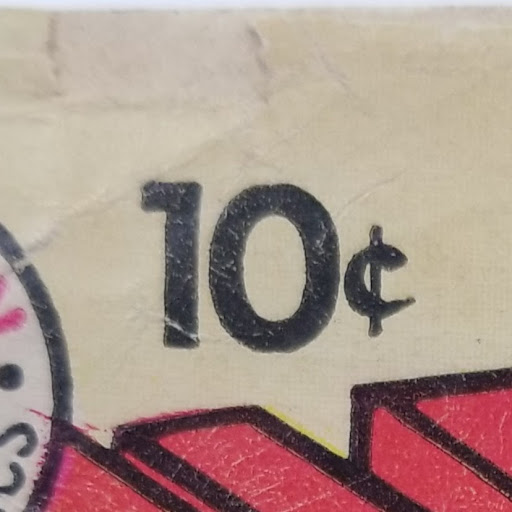

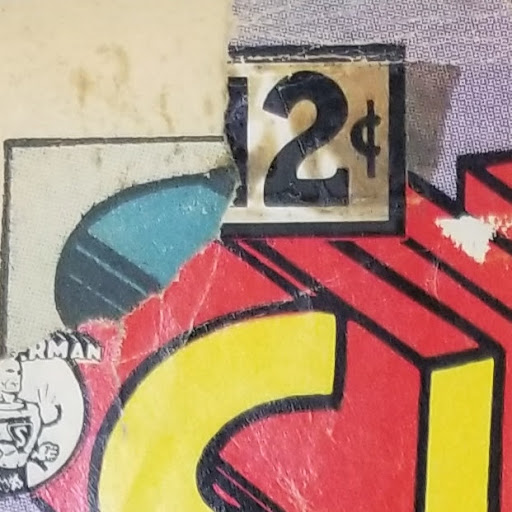

These two scraps of comic book covers can easily be dated to before 1972, based on their cover price alone.

This is where comic books come in to save the day. Comic books have changed in easily identifiable ways through time, meaning they can tell us a lot about when a site was in use. The easiest way to figure out what time frame a comic book is from is its cover price. For instance, until the autumn of 1961, the price of most comic books was 10 cents. This means that any comic book with a price of 10 cents is an object that was made sometime before 1962. We can know this information from even just a scrap of the front cover. So, if we were to discover such a scrap, mixed in with other non-organic artifacts, we could get a general idea of the age of other artifacts on site.

Artifacts that are clearly associated with a specific time, or a specific group of people, are called diagnostic artifacts. Many such artifacts exist. From black-on-white pottery (which was made by the Ancestral Puebloans around 1,000 years ago), to amethyst glass (which was mainly manufactured from 1840–1880), many kinds of diagnostic artifacts can help inform archaeologists about who used a site and when. Diagnostic artifacts are much more common than dateable, radioactive samples, and they have been a standard part of archaeological studies since archaeology has been around as a science. And, even in this age of advanced chemistry, we still rely on diagnostic artifacts to determine the age of a site much more frequently than we do radiometric dating, both because of high laboratory costs and the lack of available materials to sample. Besides, no radiometric dating technique—regardless of how sophisticated it may be—has the potential to tell us who the occupants were, or what cultural affiliations they may have had. Diagnostic artifacts often tell us those things with ease.

Comic books are a special kind of diagnostic artifact, because they are so easy to assign to a certain date range. The presence of even highly fragmented comic books can help tell us about the rest of the artifacts at a site, which aren't so easily assigned to a specific date of manufacture.

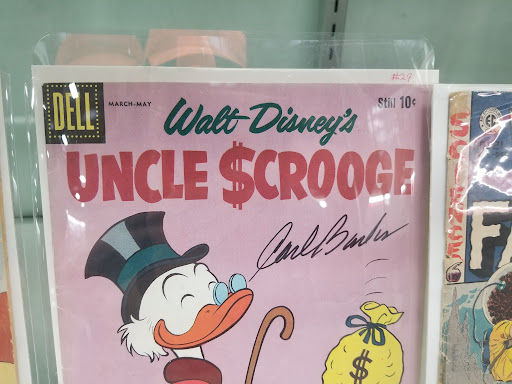

This pristine Young Romance comic book was marketed towards girls. The cover contains enough information to easily date this issue to a specific month and year.

Comic books can also tell us a lot about who was at a site and what their interests were. For example, romance comics in the 1950s were heavily marketed to young girls. So, the presence of a 1950 romance comic book might be very strong evidence for the presence of a young girl at a historical site. Sometimes, it can be very hard to tell the gender of who was at a site, so diagnostic comic books might eventually go a long way towards our understanding of the archaeology of gender. Similarly so, many comic book stories appealed to very niche segments of the population, meaning that future research into the archaeology of comic books may reveal more subtle details about the lives of those present at a particular site.

According to standard archaeological practice, anything older than 50 years old is an artifact. This means that all comic books from before 1971 can rightly be considered as artifacts, especially if they are buried at a historical site. Since comic books began their rise in popularity in the mid 1930s, they have been an important art form. Judging by the recent popularity of films which are based on comic book characters originally introduced between 1938 (Superman) and 1963 (X-Men), comic books have been deeply influential in American and global culture. Treating old comic books as artifacts will help us to figure out how these cultural icons rose to such prominence.

The villains in our archaeological story are those forces of nature which are destructive to comic books: Water, sunlight, heat, insects, rodents, and mold are all dreaded enemies to comic book collectors and archaeologists alike. The job of archaeologists is to rescue what's left of old comic books from these archenemies. The more artifacts we save, the more deeply we can understand our own history. Indeed, much more than just the history of comic books themselves will be illuminated by such research. By accurately determining when a site was occupied and who occupied it, the archaeology of comic books will be increasingly important in our analysis of many historical sites.

Anthropologists, historians, and many other social scientists have a deep interest in comic books. We have written well over 100,000 peer-reviewed journal articles on the subject. Thus, as time moves forward, tiny scraps of old comic book collections will play a leading role in the story we write about the past. Truly, even the most humble shred of an old comic book may provide powerful insight into who was at a site, and when.

So, I encourage you to indulge in your favorite comic books. Buy them, read them, collect them, and preserve them. If anyone teases you, just tell them that you're doing research on the history and archaeology of popular art. And while you're at it, explain to them how radiometric dating techniques are just the sidekicks of diagnostic artifacts.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Bringing Back Blinky Museum Collecting in the Time of COVID-19

Discovering Personal Treasures the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. In this heartfelt account, a refugee reflects on the journey that helped to define what constitutes her most prized possessions.

Taking Colorado Day by Day In conversation with author Derek R. Everett