Story

A Lynching in Gothic, Colorado?

After coming across a newspaper notice of the lynching of a Chinese man in a long-forgotten mining camp, the author undertakes a deeply personal journey into Colorado history as he contemplates who really “belongs” in our narratives about the past—and our present.

Author’s Note: Much of the racialized terminology that appears in this article is now understood to be harmful and not appropriate for contemporary usage. I have retained such terms only when quoting historical sources, and use modern terms in my own writing. Likewise, other grammatical quirks in quoted sources reflect the original typography.

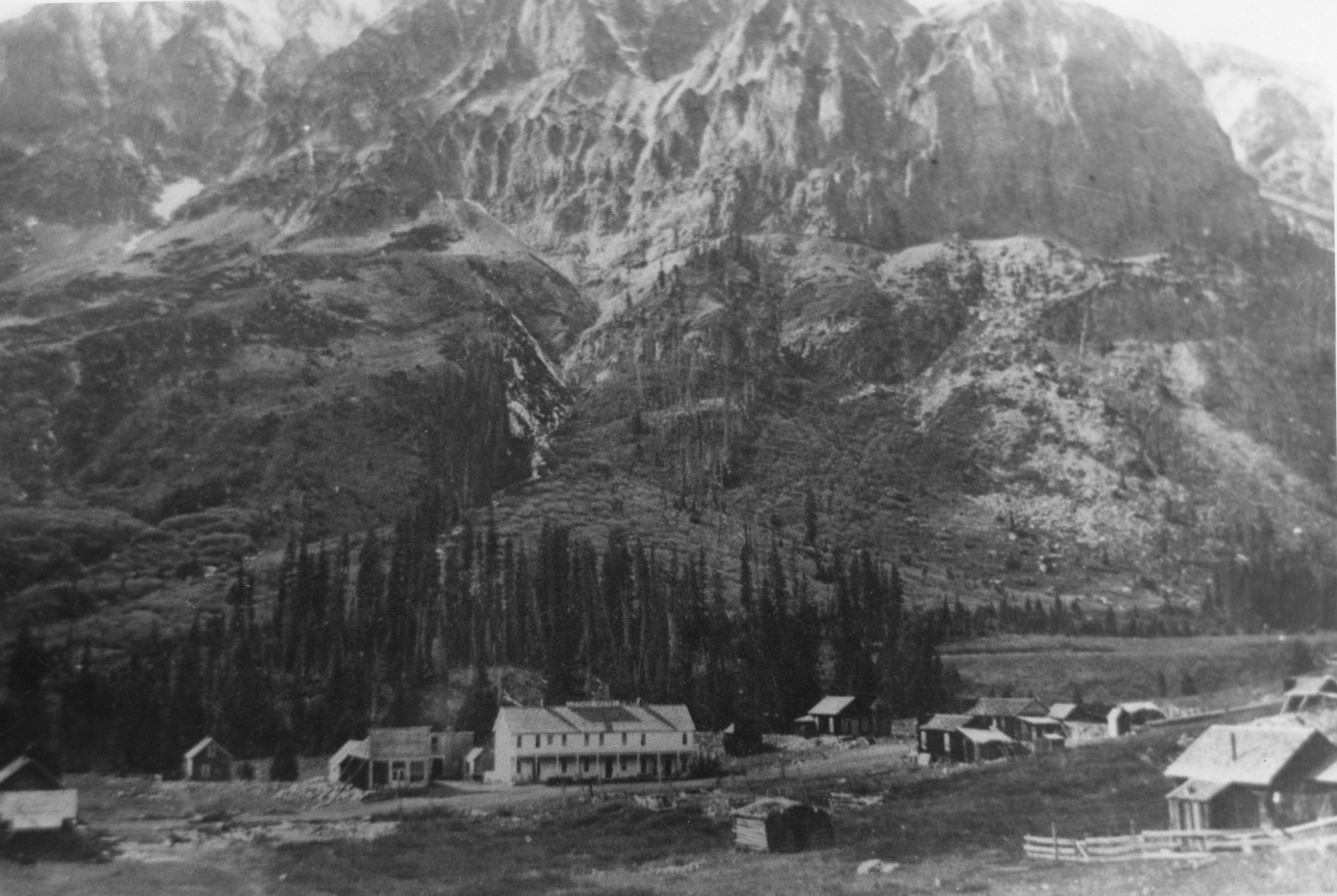

The first time I ever came to Gothic, Colorado, was in the autumn of 2009. Gothic is a ghost town, once a bustling city—a city larger in the 1880s than modern Crested Butte, situated eight miles south, is today. Mining—for wire silver, ruby silver, pyrite, galena, and gold—is what once brought people there, but now the townsite contains only some cabins and buildings that serve as the home of the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory. I made my way out there on the invitation of a friend, to carry equipment up a nearby mountain for her climate change experiment. My memories of the trip are of shimmering golden aspen forests, cows being driven down-valley, the silence of the mountains at noontime on a still day, and an early-season snowfall that dusted the high peaks the day after we finished our work. I remember billy barr (he prefers not to capitalize his name), one of the Gothic’s few year-round residents, closing up the visitor center for the winter, unplugging the freezers, and giving out the last of the summer’s ice cream to the few scientists still working at the laboratory. I felt, like many visitors past and present, entranced by the magic of the place, and welcomed by people in the valley.

Gothic today, seen from the same vantage the photographer had in the 1880s, is now a biological field station but retains much of its character as a mining town.

I’ve been back every year since that first trip. Gothic has become a place where my research group carries out long-term work monitoring alpine plants and tracing the causes of aspen forest dieback—and more importantly, a place deep with community, somewhere I belong. I admit that I have even, on occasion, felt that the mountains were mine.

But belonging requires a dividing line—a feeling that with those who do belong, some others cannot belong. This eventually brought me to a contemplation of today’s community. Who is in—and who is out?

I first began to wonder about this a few years ago, while working out of an old mining cabin in Gothic. What would belonging have meant to that past Gothic community?

Photographs of Gothic at this time show a city full of saloons, prospectors, and hopes of riches. Historical accounts of mining town life are also full of hardship—snowslides, men frozen to death, mines collapsed, disputes ending in murders, and so on. The old town hall has a few bullet holes in it, which date from this era. This frontier-driven wildness of man and mountain alike pervades the histories, and evokes, at least in me, a spirit of opportunity and exploration. I had a hard time reconciling this spirit with the clear boundaries of that world. The people who did the mining, who kept the saloons, who owned the capital, whose stories appeared in these histories—they were all white, they were nearly all men, and they never doubted that the place belonged to them.

Gothic, Colorado, featuring a prominent hotel amid homes and other businesses during the 1880s.

But who else was there, and did not belong? I started to confront this question when reading through Carl Leroy Haase’s 1971 history, Gothic, Colorado: City of Silver Wires, one late autumn I spent living in Gothic. There is a small mention, meant to illustrate the frontier spirit, of a time when Gothic hanged a Chinese man. And that is it—the narrative continues on to other topics.

My life also went on, but as the years passed, I couldn’t get the story of the hanging out of my mind. Who was this person, and what had he done? The event held some personal resonance for me. I am half Chinese myself on my mother’s side. My family’s stories and identities were familiar to me, but the only story of Chinese people in Gothic I had heard involved only a single person from a century prior, whose only relevant characteristic was being hanged—a man who did not merit being named, and who surely did not belong.

This spring in San Francisco, near where I live now, two Asian women, one 84 years old, the other 63, were stabbed. In prior weeks, other elderly Asian community members had been variously assaulted, robbed, or murdered, often at the hands of white assailants. That long-ago hanging in Gothic, the feeling of fear in my family in the present—the stories began to intersect. And so, I did some more research.

The hanging took place in Gothic on March 5, 1881, at least according to the March 11 edition of the weekly Lake City Mining Register. Several accounts of the event can be found in contemporary newspapers. The Elk Mountain Pilot, published in nearby Irwin, reported on March 19:

The mining towns of Colorado, as a general thing, are averse to John Chinaman and never allow him in the wealth producing districts when they can possibly avoid it. They look upon him as an enemy to the laborer and a bane upon society.

Not until a short time ago has the Elk Mountains been the recipient of a visit from the almond-eyed celestial. He came to Gothic under protest of the citizens and opened a "washee" house. As is usual, his cheap rates proved a serious detriment to the old time washer women of the town and caused them to become very indignant. An anti-Chinese organization was formed and the pig-tailed man ordered to leave the town instanter. This the Chinaman refused to do, and defied the organization to drive him out.

Saturday afternoon, about 4 o'clock, the organization appeared at John's house and once more requested him to “git.” But John was still imperturbable and informed the committee that he was there for the season. Seeing that argument was useless the organization took the Chinaman out and hung him to the nearest tree.

Also on March 19, however, The Elk Mountain Bonanza (published weekly in Gothic) instead reported:

It seems a Chinaman, described as "a poor, dirty, half starved specimen of humanity" was found in Flagg's saloon in Gothic. It says when discovered "a number of cool determined men" assembled for consultation. They soon arranged their plans and made ready for the attack. At a bugle call 200 strong men were called together to attack this "half starved" human being…They then marched him down the street and hung him in a public place…Her citizens uttered no protest, with the single exception of the saloon keeper, to his credit, be it said, who objected to take a man under his roof to be hung.

But it seems the hanging may not have happened in either of those ways. A few weeks later, on March 26, the Bonanza indicated that it had originally published,

a column account of the hanging of a heathen Chinee…[concluding]…with the following: "Here is the picture of our first–it is hoped our last–Chinaman hanged–in effigy."…

and confirmed by the Gunnison News, which on the same date also noted:

The hanging of the Chinaman at Gothic created great fun. The ceremony was performed with great solemnity, and a ball in the evening celebrated the event. The Chinaman was a man of straw.

So perhaps no one was murdered on March 5 that year. Regardless of whether it happened, some contemporary papers did speak out against it. The Colorado Springs Gazette noted the “Inhuman Outrage” in a column on March 19, writing:

It is foolish to get up this anti-Chinese feeling when their presence does not endanger any man's living and may be essential to our rapid growth. If there is any white man in the state who feels his inability to cope with the Chinaman in getting a living in Colorado he had better get out of the state and make room for the manlier, more industrious and stronger.

Somewhat less strongly, and closer in time to the supposed incident, the Gunnison News wrote on March 12:

We are no "Chinee lover" nor are we an advocate of cheap labor, but we have no hesitation in saying that, if the report was correct, the affair is a disgrace to Gothic and one which her fair-minded citizens will regret. A Chinaman's life is just as dear to him, as he has just as good a right to walk on God's earth and breathe God's air as any other living being…

But others felt that no harm had been done. Indeed, on March 26 the Bonanza itself said:

We confess our utter inability to see any thing inhuman in hanging a bundle of stuffed old clothes labeled "heathen Chinee."

And went on, in a separate editorial, to note:

We can't have the capital at Gothic and have in addition received a castigation from the Gazette. Gothic had now better cease its existence. But seriously this preaching up the Chinamen in opposite to every utterance by men who are as human as the Gazette and far better acquainted with the subject is injurious in every form…was the Gazette blind when it read the recital of the hanging? The Bonanza gave the facts of the hanging of a Chinaman in effigy, and had the Gazette printed our entire article its readers would have seen what would seem to have escaped the scrutiny of the Gazette, unless purposely omitted in order to fasten a crime upon our people of which they were in no sense guilty. Was that honest?

Gothic is as law abiding as Colorado Springs, and will not heedlessly take the life of even the most miserable specimens of humanity; but it has a right to make its emphatic expression of dislike for the Chinaman.

Whether a man was killed or not, a message was clearly sent. And the message was one that was heard. The Bonanza also ran a letter on March 19 from a woman in Denver:

SIR, I am a poor woman anxious to go somewhere to make a better living. Can I run a laundry in your town and do well? Have you any Chinamen? Please answer. Mrs. R.H.A.

ANSWER - You should do well here. There is no regular laundry, and if you can apply yourself to the business it will prove profitable. We have no Chinamen, and after the late expression of the people it is probable that no Chinaman will care to dwell here.

And on March 26 the Pitkin Independent wrote in strong support:

The anti-Chinese organization on Saturday last hanged a Chinaman at Gothic…Pitkin will soon have an opportunity of following suit.

In September the same year, an attempted lynching did take place in Gunnison—this one, certainly real. The Gunnison Daily News-Democrat reported that on September 22, police and sheriff’s officers narrowly held off a mob intent on murdering a Chinese man identified as Mr. L. Sing. To provoke the mob, Sing had done nothing more than open a laundry business, to the chagrin of those already doing the wash in Gunnison. The News-Democrat reported on the incident the following day:

It is not claimed that the Chinamen attempted to cut down prices, but the mere fact of his presuming to come here and start in business was enough.

Among those who were particularly opposed to this were Miss Kate Lowry, who keeps a laundry in the rear of Mr. Preston's store, and a colored woman named Harriet Jones, who was formerly employed in the Tabor House laundry. About nine o'clock these two women went to Sing's place and ordered him to quit. Words followed when, it is said, the Chinaman picked up a hatchet and ordered them to leave. Upon this Miss Lowrey picked up a wash-board and threatened to strike him. He then took a revolver from his pocket, and, so she claims, threatened to shoot her. She went out on the side walk and Sing followed her and fired the gun into the air. She then struck him over the head with a club which she had procured. The Chinaman fired three or four times in this way but always into the air, probably to attract the officers, and all the time the infuriated woman was giving him an unmerciful beating over the head and shoulders with the club. Finding that he was getting the worst of it Sing pointed the weapon at her and might have shot her had it not been snatched from his grasp by a man named Long who came up.

A crowd soon gathered and cries of "Lynch him" were heard, and for a few moments it certainly looked as if the Chinaman would be strung up then and there. The noise of the shots attracted the attention of Sheriff Clark and his deputies and the city police, and before the crowd had time to do anything, the officers were on the ground and took the man in charge. As quick as a flash revolvers were drawn on all sides. Nearly every man in the crowd had a weapon, and for a minute or two things looked decidedly squally. Several of the mob rushed forward to wrest the prisoner from the officers, but the latter drew their revolvers and ordered the crowd back. One man, said to be a gambler, had a pistol pointed at the Chinaman when it was snatched away from him by Sheriff Clark. The Chinaman was terribly frightened evidently thinking his time had come, but the officers kept the crowd back and retreated toward the jail where they arrived safely with the prisoner who was locked up.

The instigating women, along with another woman and her husband who also ran a laundry business and had come to Sing’s laundry to “smash things generally,” were only fined five dollars plus expenses ($17 total, worth about $460 today) by a local judge, with these fines paid in sympathy by members of the community. In contrast, “The Chinaman will probably come up… on charges of carrying concealed weapons and discharging firearms,” the News-Democrat concluded.

It is difficult to judge the past by modern standards, but it is hard now to see these events as anything besides hate crimes, painfully evocative of the lynchings used widely by whites against Blacks, especially in the post-Civil War South. Extrajudicial killings, carried out in public view, and reported favorably by the press, were and are a powerful form of social control and intimidation—a way to clearly delineate the line between the people who did belong, and those who did not.

I was tempted to imagine these stories as isolated incidents from the deep past. At the time, I wanted to leave them in the past, and by extension, to secure my own belonging in the present. I don’t think that way any longer, because of the answers to three questions I ended up posing to myself. There was more to learn about the situation in Colorado in 1881.

First, why the conflict over laundry work and wages? The answer comes at the intersection of capitalism and empire. The British, with United States support, fought and won several wars in China in the nineteenth century, primarily seeking to close foreign trade deficits, expand influence, and import opium to sell to the Chinese population. The Second Opium War concluded with the forced signing of the Treaty of Tianjin in 1858. The United States gained trade opportunities and diplomatic presence in China, which were later used to extract further concessions in the Burlingame-Seward Treaty of 1868. Critically, this latter treaty allowed for free Chinese immigration to the United States.

The impetus for this immigration was economic development—the Chinese were seen as a source of inexpensive physical labor for the companies building the railroads that would cross the American continent. Decades later, with the construction work gone, other economic opportunity was scarce, and returning home was often unaffordable to those workers who survived the railroads. Washing clothes was low status work, typically done by women or Black people, with long hours and low profits—and so it was work suitable for the Chinese to take on. To reduce costs and with few other rental options, Chinese laundrymen typically lived in the backs of their shops—an arrangement that enabled the white community to avoid social interaction with the people behind the work, pushing the Chinese further into the category of people who did not belong.

Thus, the Chinese in laundry jobs remained perpetually foreign, socially unintegrated in a way wholly different from the experience of some other immigrant groups, bound up in low-wage jobs where accumulation of capital and prestige was neither economically realistic nor socially permissible. And with this economic and social marginalization came conflict—in many cases with other poor people, like the white and Black women who attacked L. Sing in Gunnison. In some cases, this conflict was even encouraged by white capitalists who largely owned the major mining and railroad concerns and sought to minimize labor conflicts and displace anger over economic inequality into conflict among whites and non-whites. President Lyndon Johnson noted some decades later, “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket.”

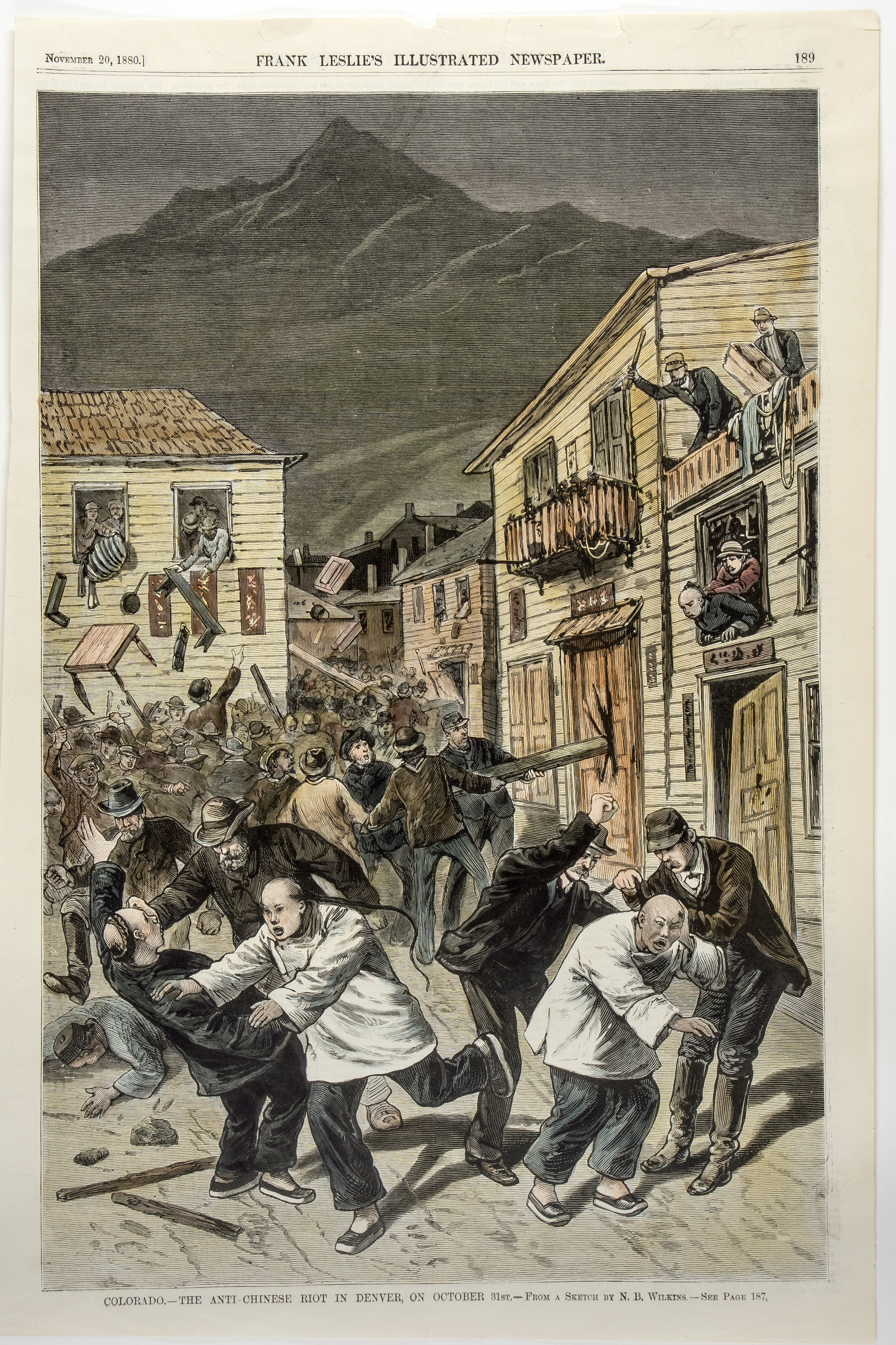

An author's illustration of the anti-Chinese riot that erupted in Denver on October 31, 1880, published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper the following month.

These 1881 stories come at a particular inflection point in American history. The year 1875 saw the signing of the Page Act, which essentially prevented the immigration of Chinese women, cutting many off from their families. The prior year, 1880, saw the signing of the Angell Treaty between the United States and China, which, “because of the constantly increasing immigration of Chinese laborers to the territory of the United States, and the embarrassments consequent upon such immigration,” restricted Chinese immigration to arbitrarily low levels—effectively protecting the interests of white American workers. And the subsequent year, 1882, saw the signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited all Chinese immigration. This law was extended by the Geary Act in 1892, which forced Chinese to carry identity papers or be deported or do a year of hard labor, and then made permanent in 1902. These laws remained in force until the Magnuson Act of 1943. The historical arc of racism is long.

Second, were these hate crimes isolated moments of violence? They were not. More than two hundred anti-Chinese incidents have been documented in the late-nineteenth-century American West. One, in Denver in 1880, was especially widely reported, and may have provided inspiration for the attempted lynchings in Gothic and Gunnison the following year. The year 1880 saw the question of Chinese immigration play a major role in the presidential contest between James Garfield and Winfield Hancock. Allegations were made that Hancock’s party was seeking to naturalize Chinese mine workers, and then to buy their votes for the presidential contest; other allegations were made that Garfield was planning to run on a strong pro-labor platform but then actually support the importation of Chinese ‘coolies’ as cheap labor after the election to reward the capitalist and manufacturing elite that supported his candidacy. This question of Chinese immigration was central to the election, especially in Denver, where an anti-Chinese parade was organized days before the election. Tensions came to a head the following day, when a group of white men entered a Denver saloon, John’s Place, and interrupted two Chinese men playing pool. According to the saloon keeper John Asmussen:

The men then commenced abusing the Chinamen, and I remonstrated with them, and they said they were as good as Chinamen, and they came up to the bar and got some beer. While they were drinking I advised the Chinamen to go out of the house to prevent a row, and they went out at the back door. After a few minutes one of the white men went out at the back door and struck one of the Chinamen without provocation. Another one of the crowd called to one of the gang inside to “come on Charley, he has got him,” and he picked up a piece of board and struck at the Chinese, which the Chinese defended against as well as they could, and tried to get away. This was the beginning of the riot.

Another Denver businessman, Mark Pomeroy, wrote:

At this time about 3,000 persons were assembled…about the houses occupied by the Chinese on Blake street; the houses were entirely surrounded by a surging, infuriated mob of brutal cowards, with clubs, stones, &c. They were breaking in windows and doors, cursing, howling, and yelling “Kill the Chinese! Kill the damned heathens! Burn the buildings! Give them hell! Run them out! Shoot them; hang them!” &c. I saw doors broken, saw men entering the houses with impromptu torches look for those who were inside hiding; saw clothes and other articles brought and thieves run away with them.

At one point, the mob went to a Chinese laundry owned by a man named Sing Lee. According to witness Nicholas Kendall, they:

commenced to breaking in the windows. A portion of the mob went into the house in the rear. They proceeded to break up everything and throw it out. There were about ten who went into the house. They caught one Chinaman [Look Young] and brought him out with a rope around his neck, and they were dragging him with the rope while he was on his back.

Look Young was eventually tortured, hung from a lamp post, beaten, and killed. By late that night, much of the Chinese community in Denver had been destroyed. A few men were brought forward on rioting charges; three men accused of murdering Look Young were ultimately acquitted in court when provided alibis by others. Diplomatic protests by Chinese businessmen were ignored by the city. The Chinese ambassador Chen Lanbin lodged a protest to the United States, but was ultimately dismissed by Secretary of State William Evarts, who claimed that the matter was outside of federal jurisdiction, that “many of the ringleaders” had been arrested, and that he had done what “the principles of international law and the usages of national comity demand.”

A year and half later the Exclusion Act was passed. On the same day the legislation was adopted, May 6, 1882, a mob of fifty people in Rico, Colorado, dragged the town’s Chinese population from their homes, assaulted them, and took their possessions. Three years later, in 1885, another mob in Rock Springs, Wyoming, saw white miners kill twenty-eight Chinese residents and drive out hundreds more. In 1902, the year the Exclusion Act was extended, another mob ran the Chinese community out of Silverton, Colorado; two restaurant proprietors were “roughly used, ropes being placed around their necks and…led out of town.” Many other similar stories in other mountain towns can be found in the archives. That is, the events in Gothic and Gunnison were not at all notable for their scope of racialized violence. Local racial violence and racist immigration policy went hand-in-hand.

Third, what forces created these nineteenth-century frontier towns that brought together white people and Chinese men? The question is most directly tied up in the expansion of railroads and the prospects of wealth associated with the expansion of mining. But these stories cannot be told without exploring how these lands became available for railroads and mining to begin with. The land around Gothic and Gunnison was part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Spain until 1821, when it became part of newly independent Mexico. In 1836 it narrowly missed becoming part of the Republic of Texas, which was later annexed by the United States in 1845, triggering the Mexican-American War. Within two years, United States forces led punitive expeditions that reached Mexico City, and by 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war—ceding what is now western Colorado to the United States. Colorado was a territory by 1861 and a state by 1876.

These western Colorado frontier towns were not empty places, open for settlement and economic exploitation. They were traditional lands of the Utes, whose Uncompahgre (Tabeguache) band would have used the land that is now Gothic. Pressure from settlers and mining interests paralleling the creation of the Colorado territory led to the development of an agency system that nominally provided rations in exchange for movement of Utes to settlements, but that often instead drove a forced dependence on wage labor and interaction with capitalist systems, and the erosion of traditional livelihoods. As the agricultural potential of eastern Colorado became more apparent, the Utes were forced to sign a series of disadvantageous treaties. One signed in 1868 at Conejos, with Ouray and other Ute leaders present, provided a single reservation for all seven Ute bands in the largely unsettled western part of Colorado. The eastern boundary of the reservation was set to “the meridian of longitude 107° west from Greenwich,” which put the future town site of Gothic, but not most of the mineral wealth of its mountains, just a kilometer east of the reservation.

By 1873, when the mining potential of the western part of the state had become apparent (especially in the San Juans and the Gunnison country), the federal government negotiated the signing of the Brunot Agreement, which was approved by Congress in 1874. The terms were agreed under the alternative scenario of these lands being taken instead by force and without compensation, so the final terms were very unfavorable to the Utes. Almost four million acres of land were taken in exchange for limited cash payments and hunting rights. The location of Gunnison, being more than “ten miles north of the point where said line intersects the thirty-eighth parallel of north latitude,” was excluded from this agreement, meaning the area remained nominally part of the reservation, into which non-Utes were not allowed to trespass.

But there was little to stop the incursions of prospectors. Mineral deposits were found all around Gothic in 1879, and mines began appearing, legally or not. The same year, calls for the removal of all Utes from Colorado grew, spurred in part by the rhetoric of Frederick Pitkin, who was elected Colorado governor in 1879, campaigning on a platform of “The Utes Must Go!”, as well as the military hostilities involving the White River Indian Agency, which culminated in 1879 with violence at Meeker. By 1880, the Ute Removal Act was signed in Washington DC, signifying that “the confederated bands of the Utes also agree and promise to use their best endeavors with their people to…cede to the United States all the territory of the present Ute Reservation in Colorado.” Another twelve million acres of land were ceded, and the White River and Uncompahgre Utes were forcibly removed to reservations out of the state. The removal was completed by late 1881, under forced march supported by the United States Army. So, the Gothic of 1879 was founded on stolen land, and the Gothic of 1881 continued only by virtue of military force.

It is no wonder that in the months prior to the removal of the Utes, in the same months surrounding the hanging at Gothic, that violence was in the air—and that the targets of this violence intersected both the Chinese laborer and the Utes. The Gothic Miner, the local newspaper, wrote on April 2, just a month after the hanging, that “Every preparation is making by the Utes to begin their hellish work of murder…Let us sweep the rascals from the reservation…Down with the Utes,…and the Chinamen.”

My historical explorations ended here.

This chapter of violence, I feel, provides a foundation for the community we see today. The mountains mostly belong to the United States Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management; the valleys are in private hands, or with large corporations whose capital and ownership are often far away. In the visitor center in Gothic, the museums in Crested Butte and Gunnison, there is little to be seen or heard of the Utes, the Chinese immigrants, or the other marginalized groups whose stories are also here. These silences make it very clear who belongs, and who does not.

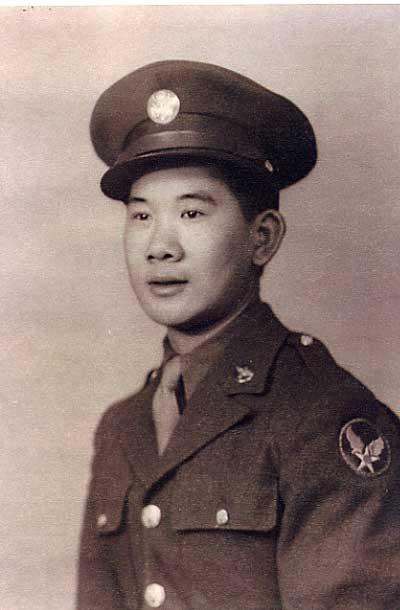

Learning these stories, I also began to re-examine whether I myself felt I belonged in this community. All the Chinese side of my family comes from farming villages near Toisan in the southern Guangdong Province. Many people from this region came to the United States as railroad laborers after immigration was opened to them. Perhaps an ancestor of mine found work in Colorado, or was witness to the events in Gothic or Gunnison. Our family history is not clear enough to say.

I do know that some of my family had immigrated to the United States by the late nineteenth century, and that by the 1930s my great-grandfather, Ben Lim, was a citizen in business among the cotton fields outside Tucson, Arizona. I know my grandfather, Edward Wong, was an aircraft mechanic in the US Army’s 14th Air Force Flying Tigers in the China-Burma-India Theater during the Second World War, and was introduced to my grandmother Lana Lim, Ben Lim’s daughter, after the war ended. They both became citizens and moved to Sacramento, California, where he had a corner grocery store, and my grandmother worked in a fruit cannery. And I know that my great-uncle, William Lee Sr., and his wife, Mary Wong Lee, operated a Chinese laundry in Washington, DC, in the 1940s and ’50s, and that her father, my other great-grandfather, discouraged others from following the same path, because of the constant hard work with little to show for it all.

We are all American now, and most of us have moved up the economic ladder. My mother was able to attend college, and I now spend my days at a university studying plants, instead of the hard life of growing them. I can read only the most basic Chinese, mix freely in white institutions and communities, and have seen far more of Gothic than I have of my family’s ancestral villages. So I felt for a while that I had crossed to the other side, to belonging. Now I am not so sure.

What is the price of belonging, if it is founded on exploitation, discrimination, and violence? What should we make of a region that until recently had an “Asian” restaurant whose logo was a slanty-eyed man, and whose population in the 2010 census included fewer than sixty non-white people out of almost 1,500, of which fewer than ten were Native American? Who is paying the price of others’ belonging? It is not possible to answer these questions honestly without this historical context. Learning is not easy. The details of these stories are hidden away on microfilm and in government archives, and the broader stories, while in public view, are not widely taught. But we do not always learn our history, as I certainly had not, least of all in school. Even my own family’s stories, and the immigration context behind them, I only have begun to learn as an adult. The silence around some of these histories is explanation enough for who belongs, and who does not.

If we have any hope of building a better future, we must remember, and learn from, our past—all of it.

For Further Reading

The historic newspapers cited in this article are available through History Colorado’s Hart Research Center. Many of them are also available online through the Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection. Additional information about the history of Gothic can be found in Carl Leroy Haase’s Gothic, Colorado: City of Silver Wires (Western State College of Colorado, 1971). William Wei’s Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State (University of Washington Press, 2016) is a seminal survey of Colorado’s Chinese community, and the account of Denver’s anti-Chinese riot in 1880 is especially strong. Jean Pfaelzer’s Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans (Random House, 2007) offers an overview of the discriminatory measures leveled against Chinese Americans, while Paul Siu’s The Chinese Laundryman: A Study of Social Isolation (New York University Press, 1987) examines the history of Chinese men in that profession. A broader exploration of the history of Colorado’s Indigenous peoples can be found in Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2014) and Sondra Jones’s Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People (University of Utah Press, 2019). Additional details of treaties can be found in Paul O’Rourke’s Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado (Bureau of Land Management, 1980). An exploration of concepts underlying these race and class conflicts can be found in W.E.B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction in America (Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1935) as well as in numerous later sociological texts.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Immigration to Colorado: Myth and Reality For most of its history, America has been a haven for those seeking a better life and a refuge for those fleeing for their lives. Indeed, since its inception, America has been an inspiration to others, a place where the downtrodden could find hope. Among the proponents of immigration was President John F. Kennedy, who laid out his inclusionary vision of America in his 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants.

“Is America Possible?” The Space Between David Ocelotl Garcia’s and Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Worship

Vision and Visibility Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice.