Story

“A Lasting Disgrace”

Exposing Abuse at the Fort Lewis Indian School

In 1903, The Denver Post investigative journalist Polly Pry exposed abuses at the Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School that shocked the nation. Her reporting brought to light the mistreatment of Native children that was all too common at boarding schools throughout the nation.

The Fort Lewis Indian School in southern Colorado was one of many boarding schools that proliferated throughout the United States, especially in the West, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These schools’ purpose was to assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream American culture, and eradicate their own tribal culture, language, and identity. Indigenous children were removed from their families, often by coercion, force, or without the consent of their parents. Immersed in EuroAmerican culture, forced to cut their hair and dress in American-styled uniforms, Native children were educated in speaking, reading, and writing in English, schooled in standard EuroAmerican subjects, and trained in vocational trades.

When the Fort Lewis Indian School (note: this school was located in Hesperus, nearly twenty miles west from where present-day Fort Lewis College stands) was founded, in 1892, it housed five Navajo, sixteen Southern Ute, and twenty-six Mescalero Apache students, according to Majel Boxer, chair and associate professor of Native American and Indigenous studies at Fort Lewis. The highest enrollment was in 1899 with approximately 313 students. In 1909, there were forty students in attendance and it officially closed in 1911.

While the school was open, inspectors were sent to look into alleged misconduct on several occasions, but came up short. That’s when investigative journalist Polly Pry stepped in. In 1903, with the help of a whistleblower, she exposed the school’s troubling history. Her reports, shared below, include mention of sexual assault of children.

Investigative reporter Mrs. Leonel Ross (Campbell) Anthony wrote under the pen name “Polly Pry.”

“Polly Pry Lays Bare the Evils of the Fort Lewis Indian School...Employees Tell the Story of Outrages” was the headline that confronted readers of The Denver Post on March 21, 1903. The Post’s own investigative reporter Polly Pry—Leonel Ross Campbell by birth and the Post’s first female reporter—broke the news in a full-page exposé. The article began with a letter written to the Post by a Mrs. John Morrison Foss, a former employee of the school, who alleged “one official of the school is drunken, and according to the statements of numerous girls, takes undue liberties with them.” Mrs. Foss continued,

Some of the stories told to me by inmates were shocking in the extreme, and I had no reason to doubt their truth. I know that this is a matter for the federal authorities to ferret out—but they never will. It has been going on for years.

Mrs. Foss hoped that the Post, “which has demonstrated innumerable times that it is not afraid to tell the truth and to take part of the poor and the defenseless,” could call the attention of the proper authorities to the “wrongs which exist at this institution, and which the state officials can neither reach or remedy.”

Acting on Mrs. Foss’s appeals, Pry visited her in Salida. Working as a cook at the school from October 1901 to January 1902, Mrs. Foss became acquainted with the management of the school and heard of the treatment to which the girls were subject. In the interview with Pry, Mrs. Foss confided, “I have felt ever since I left the school that it was a duty I owed those little children to at least make public what had been told me and what had come under my own observation.” She also disclosed that there had been two or three investigations of the school by national inspectors, but that Dr. Thomas H. Breen, the school’s superintendent, had been notified in advance so he was able to conduct the tours of the school himself, and the inspectors failed to find anything amiss and Dr. Breen retained his position.

Mrs. Foss went on to describe an environment which was of a “character to horrify anyone with a grain of decency in his soul,” specifically detailing a situation in which a fourteen-year-old girl, Maria Montoya, was sent away from the school, “having become pregnant.” Mrs. Foss’s student assistants in the kitchen said a prominent employee of the school was responsible. One of the girls, Rosa, charged that the employee “bought her [Maria] clothes to wear and found her a place to stay, and more, he has made the same proposals to me a thousand times.” Rosa continued, saying that she had been there since she was eight years old—being sixteen at the time—and that this man had been trying to fondle her before she had been in school a month. Frightened, she alerted the matron about what had happened. The matron threatened to physically punish her for making such allegations. Intimidated into silence, she didn’t tell anyone because “it wouldn’t do any good—but through all the eight years that she had been there he had persecuted her.”

Pry quotes Mrs. Foss as saying “I tried to look after the girls who worked with me, and talked with many of them,” as she described how one thirteen-year-old girl came back from the school hospital, trembling and crying. After much questioning, she told Mrs. Foss that “this same official had tried to take liberties with her, and said ‘My dear little girl, don’t you know that God created you for this very purpose. That’s the reason he made you a little woman.’” After this encounter, which had been interrupted by the arrival of someone in the building, Mrs. Foss sent her own daughter along with the girl whenever she had to visit the hospital. When asked by Pry whether she had said anything to Dr. Breen or his wife about the experiences of the girls, she admitted that she hadn’t and replied, “Of course, you understand that it would have done no good and, moreover, I would have been instantly discharged.” She went on to say:

I do not want to harm anyone, but I feel that something should be done for those children, and that no man should be permitted to have charge of them who abuses his privileges and takes advantage of his opportunities as I have every reason to believe has been done at Fort Lewis.

She described yet another incident involving the official, who assaulted another girl, Katie, in the days preceding Mrs. Foss’s departure from the school for a new job in Durango. Katie tearfully begged Mrs. Foss to allow her to leave with her, which she was allowed to do. After staying with Mrs. Foss for a month, Katie returned to living with her father. Mrs. Foss asserted:

You could never doubt that she both feared and hated that official....For that matter the majority of the little girls felt the same, but they were afraid to speak. They would say, “It is no use telling anything to a government employee, they simply order you to shut up, they don’t care what happens to us, we are only Indians.”

Concluding her interview with Mrs. Foss, whom she described as having a “frank and convincing candor” and an “honest and fearless woman” who could not keep silent where there were little girls to protect, Pry then visited the school. Her first impression of the Fort Lewis Indian School was that the institution was in “a deplorable condition and in sad need of complete reorganization and rehabilitation.” She met with the school’s superintendent, Dr. Breen, who seemed “somewhat annoyed” by Pry’s appearance, and who Pry described as flying the “signs of dissipation.” Dr. Breen was indisposed at the moment and instead sent for his clerk, John Harrison, to lead Pry on a tour of the institution.

As he showed Pry the place, Harrison enthusiastically reported that Dr. Breen did not believe in rules and regulations and that the employees were at “perfect liberty” to do what they pleased. “I like it. It’s the right spirit—broad and liberal and as it should be—and we take advantage of it by having very good times.” Pry observed that there were eighteen or twenty buildings, mostly remnants from the school’s prior life as an Army fort, each in various degrees of dilapidation and decay. Only the girls’ dormitory and the dining hall were new and in good repair. One hundred twenty-two pupils were crowded into two buildings and slept two, or in some instances, three in a bed. Pry described the sanitary facilities as crude and cleanliness as “almost an impossibility.” At the time of Pry’s visit, the hospital had been given to one of the resident teachers, leaving the school with no hospital. All this despite a $25,000 appropriation in 1900 to build a new hospital and electric light plant, among other improvements. Pry further observed:

There is no manual training school...no physical culture, no carpentering, no blacksmith, no domestic science—no—in fact, as far as I could learn, there was literally nothing being done to properly equip the children entrusted to the care of the school....They shift for themselves.

Pry determined that the school was run solely and wholly for the benefit of the superintendent and that the Indigenous children were “necessary evils” for whom Dr. Breen was allotted $173 per child. Taking together Mrs. Foss’s allegations and Pry’s own observations of the poor administration of the school, Pry declared, “This government owes these little ones something better.” She finished her exposé by stating that an investigation should commence at the Fort Lewis Indian School.

Shortly after the startling revelation of the gross misconduct directed at the Indigenous students at the school, its dilapidated state, and mismanagement, Pry published another piece, “Horrors of Indian School Verified by New Witness,” on March 26, 1903. The witness, J.R. Hughes of Durango, wrote to The Denver Post with his own account of what he had experienced as an instructor at the Fort Lewis Indian School, and corroborated the charges made by Mrs. Foss against officials at the school. Hughes’s report included even more graphic and disturbing details of the sexual assault which Mrs. Foss alluded to, the least being that “every Saturday the employees sent to Hesperus for liquor and there was a general drunken orgie [sic], during which no attempt was made at concealment in regard to their performances with the Indian girls.” Hughes added that there used to be “a good many Navajo girls at the school, but when several of them were sent away from school because they were to become mothers, the Navajo people ceased to send their girls to that school.”

Hughes, describing himself as “one against a crowd” spoke to the men who were involved and begged them to stop. He wrote to the Indian department in Washington, DC—presumably the Bureau of Indian Affairs—and detailed the matter for them. Hughes said an inspector was sent out, but since Dr. Breen was notified of his visit, nothing was either seen or heard. He further revealed that “during the past three years forty-three government employees have been transferred from this school, there being constant trouble between the officials and the employees.” Hughes provided the newspaper with his collection of documents from the Indian department and stated he was ready to prove any allegation he made. He ended his letter by saying, “I hope the Post will never let this rest until they have rendered these people powerless for further evil. The Lord surely moved the women who brought this to the light.”

A New Path

Durango’s Fort Lewis College can trace its history back to the school described in this article. Although the college is at a different location—it was located about twenty miles away in what is now Hesperus—the legacy of the Fort Lewis Indian School continues to impact the present day. In recognition of that past, the school has created a Committee on FLC History to guide the interpretation of events and to create an educational and cultural environment that supports Native American students.

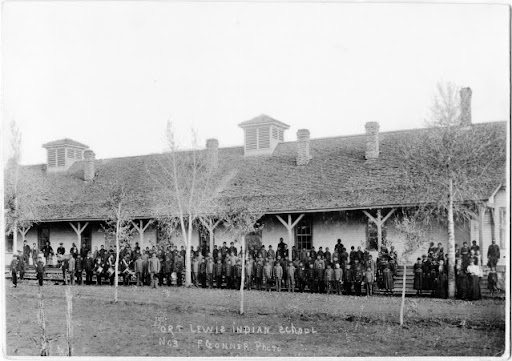

Fort Lewis Indian School No. 3 (date unknown).

Pry’s initial article, the allegations made, and the documentation given by J.R. Hughes compelled the Post to put the matter before Theodore Roosevelt, then president of the United States, and before the proper officials in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By April 10, 1903, The Daily Journal of Telluride announced that President Roosevelt had ordered an immediate investigation into the accusations made against the officials of the Fort Lewis Indian School. The Daily Sentinel of Grand Junction, itself home of the Teller Institute—another Indian school that operated from 1886 to 1911—noted, on April 24, that Dr. Breen was once in charge of that institution. The Sentinel repeated the Post’s charges against Dr. Breen, as being “the principal in a number of drunken and obscene orgies, in which he compelled the Indian girls to participate and also to being the father of several children by Indian girls.”

Glenwood Springs’s The Avalanche-Echo reported on April 28, 1903, that Commissioner Tanner of the Indian Bureau requested the Post to furnish him with the evidence of charges they had leveled against Dr. Breen. The San Miguel Examiner of May 9, 1903, stated that “If all accounts are true Superintendent Breen should be transferred to Leavenworth.” Finally, on July 27, 1903, The Aspen Daily Times published that Superintendent Breen had been discharged through the efforts of The Denver Post:

The investigation has proved that Breen is guilty of drunkenness and other conduct unfitting to his office, and that he is mentally and physically incapacitated. W.S. Patterson of Oklahoma will take his place.

Until it closed officially in 1911, the government and school’s administration continued the practice of attempting to assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream society based on nineteenth century, EuroAmerican notions of education and training in order to induct them as members of the white citizenry. The damage of Indian schools like Fort Lewis and the Teller Institute to the physical health, mental wellbeing, and cultural identity of its pupils extended for generations. Although these words of Pry relate to the Dr. Breen scandal specifically, they can be taken in view of Indian schools more broadly:

It is a story to fill the heart of every fair-minded, decent person with white-hot indignation. If we did not know our world so well it would seem incredible. As it is, it can only be characterized as absolutely bestial and a lasting disgrace to the fair name of Colorado—a disgrace which only the most sweeping changes can obliterate.

More from The Colorado Magazine

“Obliterate and Forget” A Brief History of Federal Indian Boarding Schools in Colorado

Vision and Visibility Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice.

The Post-NAGPRA Generation The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Thirty Years On