Story

The Kingdom of Bull Hill

The 1893 Cripple Creek Strike was one of the earliest and most important labor conflicts in Colorado history. This first-hand account, written nearly ninety years ago, shows the extreme measures they took to fight for their rights in a world that was increasingly hostile to organized labor.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Colorado Magazine, we’ve selected some of our best articles from the last hundred years to republish online. This article was originally published in the September 1935 edition, and has been reproduced here as it was originally published. Some additional photos have been added.

Mr. Pfeiffer was born in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1864. He came to Colorado in 1882 and worked as a bank accountant. In 1893 he went to Cripple Creek and Bull Hill and lived through the troublous times there. Upon the creation of Teller county he was appointed one of the first county commissioners. He moved to Denver in 1907 and has since resided here, holding a number of important positions.

The Cripple Creek mining district, located in the western portion of El Paso County, came into prominence just after the panic of 1893. The silver mining camps were dead and the miners looked to the new camp as a life-saver and flocked into it from the older localities. The population of the entire district, both towns and hillsides, increased rapidly, as did the mining activity also. The Victor, Isabella, Pharmacist, Zenobia, and Free Coinage were some of the prominent mines on Bull Hill, although there were many others of lesser magnitude.

The town of Altman was platted in the summer of 1893. It was about three miles from Cripple Creek and up hill more than 1,000 feet, its elevation being about 10,700 feet. It was nine miles in an air line from the top of Pike’s Peak. A population of some 1,200 was served by stores, boarding houses, post office, a livery stable, and five saloons.

The first “Miners Union” of the district was organized there that summer, a branch of the Western Federation of Miners. The mines were working eight-hour shifts, with one-half hour off for lunch on the company’s time; the pay was $3.00 per day. Some mines were working three shifts, day shift, night shift, and “grave-yard” shift, as it was called; thus it was possible to employ more men and get out more ore.

The first sign of trouble came in August, 1893, when the then superintendent of the Isabella Gold Mining Company, at the shaft of the Buena Vista mine, had notices posted to the effect that after September 1st the hours of the shift would be ten, nine for work and one for lunch, but with no increase in pay. Trouble came to the “super” without delay. He came to the mine daily from Cripple Creek in a horse-drawn cart. On the morning of the day when the order was to become effective, as he approached the mine, he was surrounded by the incensed miners and addressed in most vehement language. He very unwisely tried to bluff his way out of a very tense situation. Not until a loud voice was heard saying, “Bring on that can of tar,” did he realize his predicament. He was pulled out of his cart and threatened with violence if he did not rescind the order. After a few minutes of talk he decided to comply and I am sure he posted the notice at once and without the knowledge of the owner.

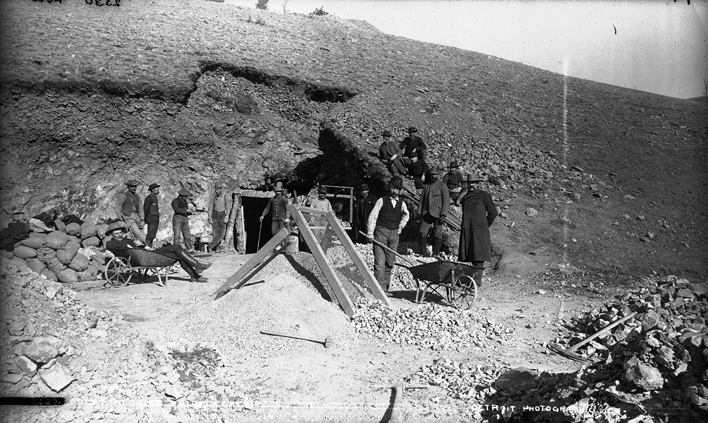

The Gold King Mine near Cripple Creek, 1892.

“If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again,” was the motto this “super” seemed to follow, for he finally succeeded in getting all the owners of the large mines into an agreement to put the ten-hour shift into effect. So on January 20, 1894, notices were posted at all the mines. The following day, as usual, he drove over from Cripple Creek in his horse-drawn cart, a deputy sheriff on horseback preceding him, and another deputy sheriff on horseback following behind. He was just passing the “Dougherty Boarding House” when he was met by a crowd of men and stopped; another crowd of men in the rear cut off his retreat; his two guards were also captured.

He was dragged from his cart and subjected to rough treatment. He was walked down backward by two husky fellows to the wagon road in Grassy Gulch; then down the road toward the old Spinney Mill, all the time being told that he was to be hanged at the mill. Upon arriving there, however, the gang relented. He was forced, nevertheless, to kneel down in the road and take an oath that he would never return to the district unless invited by the miners themselves. The horse and cart were returned to him, an escort provided and he was set out on his way down the old Cheyenne Canon [sic] road to Colorado Springs.

Following this event, around February 1, 1894, the “Kingdom of Bull Hill” was born. An army was recruited, picket lines were established and patrolled by squads of men selected by the officer of the day; no one was allowed to enter or leave without a proper pass, the result being that we were without the confines of the United States. We were a band of outlaws; the mines were closed; a few watchmen were permitted to remain on the properties, but the owners were not allowed to work them. The war was on.

At this time in my story it is proper to say that the Governor of the State was Davis H. Waite, a Populist, who had been elected in 1892, was [sic] a well known advocate of union labor and no doubt a friend of the striking miners.

The mine owners appealed to the authorities of El Paso County to take steps to restore possession to them of their properties. To this end the County Sheriff organized a “posse” to the number of 1200. In the course of events the Sheriff had his force encamped near the town of Gillett, about four miles from Altman. Meanwhile, a force of one hundred detectives were employed in Denver to attempt to regain the possession of the mines–it was said they would bring plenty of arms and a cannon.

Night-shift miners, gathering outside the Strong Mine. The photo caption identifies the mine as “one of the great mines of the district.” This building and a nearby steam boiler were purposefully dynamited on May 24, 1894, to repel Sheriff deputies approaching Bull Hill.

The miners appeared to be well entrenched in their stronghold, with guns and a fair supply of ammunition, also a “Johnny wagon.” This was a wagon rigged with an electric battery, spools of wire and a supply of dynamite to be used as occasion arose.

The roads and trails were planted with charges of explosives ready to be set off. It was said that a cannon mounted on the bluffs above the Victor Mine was a part of the equipment. This, however, was not true. It was only a bluff, the artillery being a round log dressed up for the part. A big timber was fashioned into a bow gun, grooved in the center so that a beer bottle filled with nails and other missiles could be projected quite a distance, in case the fighting was close. Steam was kept up at the Pharmacist Mine to be used in blowing the whistle for signals, also as an alarm. When an alarm was sounded all men responded, the team was hitched to the “Johnny wagon” and off they went to investigate. It was a virtual state of siege for a while during the months. With much bad weather, snow and, as spring came on, rain, the pickets suffered, but they stuck to their posts.

Let me here digress to personal affairs. When the strike was called I was working on a mine and living in Altman. At the same time, with others, I was trying to make a “stake” in a lease on a mine. We had a good lease on a property which we lost by reason of the trouble and the owners afterward took out two million dollars! One of the partners had been a cadet at West Point.

During his fourth year he was dismissed for his part in hazing a fellow student. He drifted west and became a good miner. We became such close friends that he was taken into our home as one of the family. He came from a fine southern family. Because of his West Point training he was selected to be general of the “army.” He mapped out the territory and laid out the plan of a defensive campaign. Owing to his wise counsel to the men no property damage resulted, with one exception, to which reference will be made later. He was opposed to any destruction, although he had a hard time in restraining many of the so-called “fire-eaters” and extreme radicals. With his knowledge of military affairs and law, during the hostilities, he effected an exchange of prisoners with the authorities of El Paso County. This, he said, was a recognition of the rights of belligerency and was his greatest triumph.

Officers of the Colorado National Guard, encamped at Bull Hill during the 1894 strike.

From the beginning affairs began to get to a stage where there must be a final “show-down.” Each side of the controversy was becoming desperate. The month of May was a most trying one, with its heavy snows and rains and the men on picket duty began to complain. Also it was difficult to obtain food and other necessities. The railroad from Florence to Victor had just been completed and a train bearing detectives from Denver was en route. They were reported to be well armed and had on board a cannon. Then arose the most acute situation of the war.

The “general” decided it was time to make a demonstration of force and, as such, it was to be one of terror. As the train approached slowly on a curve in sight of Victor the shafthouse of the Strong Mine was blown into the air. The train halted, then backed down to a station called Wilbur. At the blown-up mine two men were trapped. They were taken as prisoners to Altman, held a time, and then exchanged for three prisoners held in jail in Colorado Springs.

After the train with the detectives aboard was stopped at Wilbur the miners planned to capture the whole outfit. A locomotive and cars were manned and the raid was on. The men were so eager to accomplish their purpose that in their enthusiasm the approach was far too noisy and they were discovered. A battle ensued, resulting in the death of a deputy sheriff who had been one of the guards of the offending superintendent, and three miners were captured. The attacking forces were compelled to retreat, but the detectives made no further effort to renew the combat and returned to Denver. Hell began to pop. The El Paso County “posse” began preparations to take Bull Hill. Governor Waite came on the Hill and gave the men a talk. He had ordered out the state militia and after some tense days General Brooks and his troops marched into Altman.

Were they welcome? I’ll say they were! They received a royal welcome from the men, even though they did bring along the sheriff, who had warrants for the arrest of some four hundred miners. A few of the miners gave up and were taken to Colorado Springs to jail. Had the troops not intervened just at that time between the El Paso forces and the miners I am of the opinion there would have been much blood shed.

After a number of conferences between the Governor and representatives of the miners and mine owners, the trouble was settled. Eight hours’ work with the lunch time of one-half hour on the men’s time was the result of the compromise.

Many outrageous things happened during this “war.” One of them occurred at Colorado Springs when the Adjutant General of the State was taken from his hotel and was tarred and feathered. Old Tom Tarsney did not deserve such treatment. By whom and by whose orders? Thus endeth my story of “The Kingdom of Bull Hill.” Altman is now extinct.