Story

Nine Justices and One Colorado Lawyer

The Landmark Romer v. Evans Gay Rights Case

In 1995, Boulder attorney Jean Dubofsky stood before nine U.S. Supreme Court justices to plead the case against Amendment 2, the 1992 amendment to the Constitution of the State of Colorado denying protections to gays and lesbians. On May 20, 1996, the Court ruled the amendment unconstitutional.

This essay first appeared in the November/December 2016 issue of Colorado Heritage, and is an edited excerpt from the author’s book Appealing for Justice: One Colorado Lawyer, Four Decades, and the Landmark Gay Rights Case: Romer v. Evans.

It’s hard to say where the story that became known as Romer v. Evans began. Maybe it was in the 1980s, when homosexuals started to emerge from the closet, determined not only to fight for their equal place in the world, but to battle for their lives as AIDS began taking the lives of so many gay men. Or maybe it was when local governments in Colorado passed human rights ordinances to protect gays and lesbians from the discrimination that was so prevalent, or when scores of anti-gay religious and cultural organizations moved to Colorado determined to push back against those efforts.

Surely it had begun by November of 1992, when Colorado voters passed the anti–gay rights Amendment 2. A national boycott of the state ensued, then one legal battle after another for the next three years. Following two courtroom trials and two appeals to the Colorado Supreme Court, Romer v. Evans arrived before the nine justices of the United States Supreme Court on October 10, 1995.

More than three years after Colorado’s Amendment 2 passed, the U.S. Supreme Court struck it down in a 6–3 decision, with Justices Scalia, Rehnquist, and Thomas dissenting.

In the lead-up to the 1995 Supreme Court term, the national legal press turned the spotlight on Romer v. Evans—so-named for Colorado governor Roy Romer (who personally opposed the amendment) and plaintiff Richard G. Evans, a gay man who worked for Denver mayor Wellington Webb. “[It] has become the most watched case of the term,” wrote the Washington Post; it is a “historic battle” and the decision will be “hailed as one of the decade’s most important civil rights rulings,” wrote the Rocky Mountain News, calling it a “watershed case” and not just for the state of Colorado. The ruling portended “enormous consequences” for the gay rights movement nationally and for all the legal battles down the road, added the long-running LGBT newspaper the Washington Blade.

Jean Dubofsky, a relatively unknown appellate attorney from Boulder, Colorado, soon would be standing before nine Supreme Court justices to argue the plaintiffs’ case. She felt ready. The immense weight, the responsibility, they were there too. But mostly, she felt ready. After three years of preparation, she had done all she could do. It was going to go however it was meant to go, she thought to herself.

When Jean’s cab pulled up in front of the U.S. Supreme Court on that clear, crisp Indian summer day in October of 1995, she saw bedlam in every direction. On the sidewalk, in the court plaza, and on the streets. Two long, ragged lines snaked around the block, one for those with tickets and reserved seats and another for those without tickets, waiting, hoping they would be allowed inside the Supreme Court chambers to witness the proceedings for themselves.

The front of one line was more a disorganized campsite than a line. Chairs, sleeping bags, and backpacks, along with remnants of a large supply of half-eaten meals, lay along the sidewalk. The most determined of the crowd had spent the night, to improve their chances of getting one of the few open spots inside the courtroom.

Pat Steadman was one of those near the very front. The young attorney from Colorado had traveled to Washington for what would prove to be one of the most emotional days of his life. Fifteen years later he would rise to become a well-known and distinguished member of the Colorado State Senate. But it was his three years campaigning for gay rights and organizing lawyers in his home state to prepare for this legal fight that landed him on the doorstep of the high court this October morning.

In spite of the day’s significance, Steadman appeared rumpled and disoriented, blurry-eyed and unshaven. He’d camped out on the sidewalk all night to be one of the first in line and get one of the few remaining seats inside the court Chamber. Each side had been provided a limited number of reserved tickets, but there hadn’t been enough for everyone involved in the case. Steadman had given his reserved ticket to another who’d worked so hard.

In addition to lines, groups were milling about—some small, some large, some with signs and banners, others marching in circles, shouting messages, all of them there to state their case or show support or simply to be present for that important day. It was a bit of a circus, but a relatively dignified one, as if the location and issue before the court demanded that.

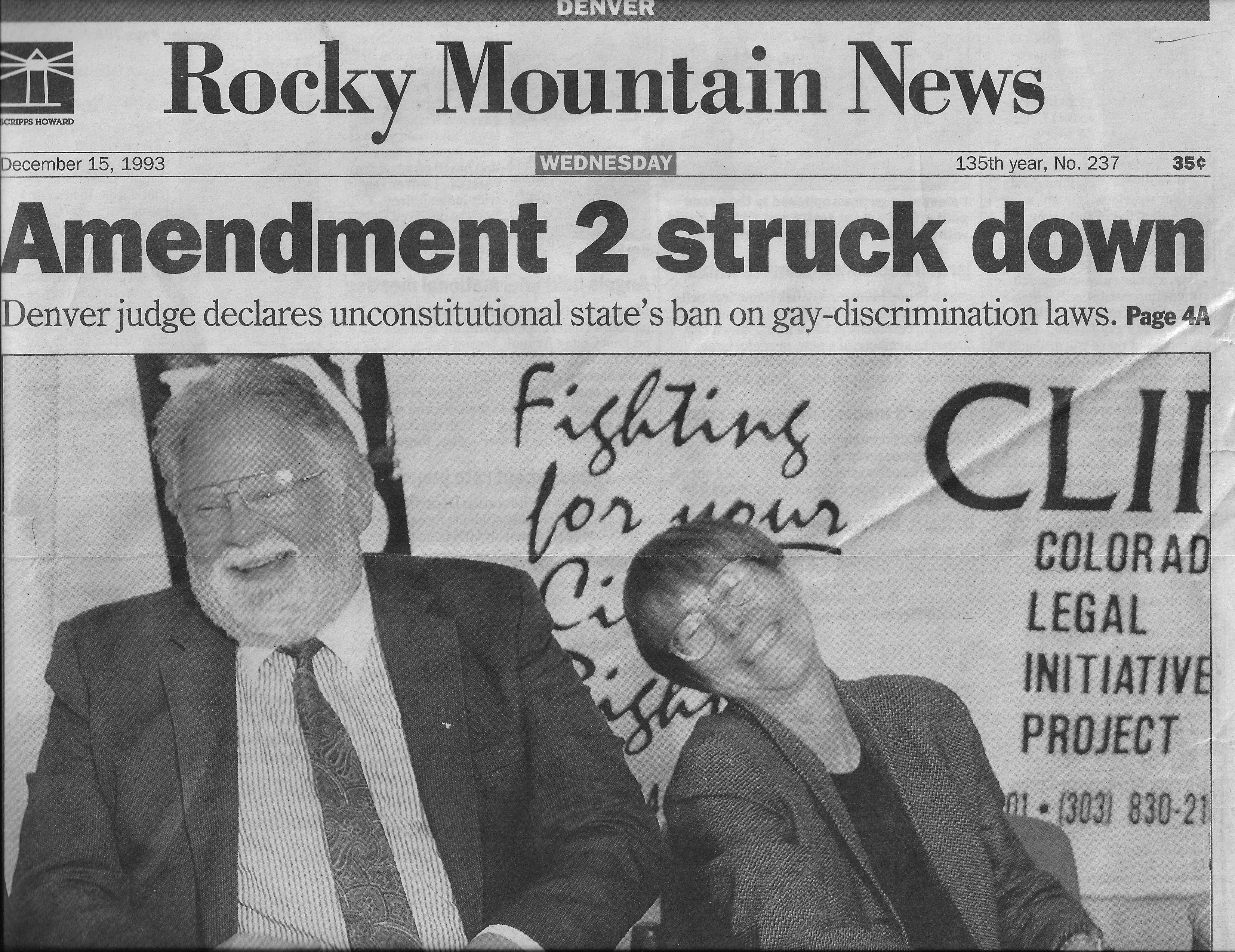

In 1993, a state district judge ruled Amendment 2 unconstitutional, setting the stage for the State Supreme Court and U.S. Supreme Court rulings that followed.

No one seemed to notice as Jean made the long climb up the steps, all fifty-two of them, leading to the entrance of the Supreme Court, past the towering columns at the top, and through the seventeen-foot-high cathedral-sized bronze doors. She wondered to herself if every individual who entered there was made to feel so Lilliputian. This time she moved down the Great Hall that led to the oak doors of the Chamber, the all-white marbled hallway lined with busts of former chief justices—John Marshall, Roger B. Taney, William Howard Taft, Charles Evans Hughes, and Earl Warren. Jean was flooded with images of the sacredness of the place and of the history that had been made there.

Maybe Jean Dubofsky should have been awed by this beautiful marble temple of justice, but she wasn’t. She’d lived among the architectural symbols of democracy during her years working on Capitol Hill, when she’d walked along this sidewalk fronting the Supreme Court almost daily, and she’d always felt comfortable there. And she still felt comfortable this day, even with the special treatment she was accorded, the ability to simply ascend the steps and walk through the doors as if she truly belonged.

At exactly ten minutes before the hour, Jean Dubofsky and two lawyers who’d been by her side for years, Rick Hills and Jeanne Winer, entered the Chamber together, and made their way to the front and through the rail to their designated place. The room was packed.

The Supreme Court Chamber had a stately feel, but, except for a thirty-foot ceiling, it was a surprisingly small and intimate space. Jean took her place at the long attorney’s table that sat three feet below the slightly arched majestic mahogany bench where the justices would reside. The floor-length ruby-red drapes, fronted by four more soaring white marble columns, hung like a theatre curtain behind the bench. At exactly ten o’clock the justices slipped through three slits hidden in the curtains and, without ceremony, took their seats.

Every nook and cranny, every one of the churchlike pews in the Chamber was filled, jammed with people, elbow to elbow. It had been the hottest ticket in town for weeks. Jean couldn’t see or didn’t have time to see who else was there or where they were sitting. She was facing forward, her focus totally on the nine justices sitting in front of her. She didn’t know that Betsy Levin, the University of Colorado Law School dean who had extended her hand to Jean years before, had waited in line, too, and had gotten the last of the eighty seats reserved for members of the D.C. bar. Nor did she know that Boulder mayor Leslie Durgin, who was battling breast cancer, had skipped a scheduled treatment in order to attend. Jean knew that Richard G. Evans, the named plaintiff, was somewhere a few rows behind her, but not that he had already begun to cry.

Protest groups suspended their boycott of Colorado following the 1993 court decision ruling Amendment 2 unconstitutional.

Jean was gratified to see Ruth Bader Ginsburg sitting as one of the nine. Josie Heath always liked to say that if Jean had stayed on the Colorado Supreme Court, she, too, might have someday found a seat among those justices. Jean was sure that would never have been the case, yet she and Ginsburg could look in the mirror and see a resemblance to the other in the roads they had traveled. They shared Harvard Law and Ladies’ Day and a lifetime of work seeking justice for others. They both had married attorneys who championed their careers in the law and were partners in raising their kids. Both had been excluded and demeaned and had found barriers along the way but simply walked around them to find their own path. Each figured out how never to reach too far, too fast, to instead just do the piece of work in front of them and do it well.

Once the justices were comfortably seated, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist began simply. Without ceremony or greeting, he gave barely a nod towards the state’s counsel. “We’ll hear argument now in Number 94 1039, Roy Romer v. Richard G. Evans,” he said.

Tim Tymkovich, the solicitor general for the state of Colorado, was already standing at the podium, as he had been instructed, ready to begin as soon as the Chief Justice recognized him. The attorneys for both sides had received guidance about what to do, where to sit and stand, what to say, and how to refer correctly to the justices—Rehnquist would be “Mr. Chief Justice”; the others simply “Justice.”

“Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the court,” he began, sounding calm and confident. This case, he said, was about the authority of the state over how to allocate lawmaking powers among state and local jurisdictions when it came to special protections for homosexuals, and the sole question was whether or not the state can reserve those lawmaking powers for itself. He cited James v. Valtierra, an earlier case decided by the court, referring to it as the definitive case that “authoritatively” resolved this question. That was as far as Tymkovich got before Justice Anthony Kennedy interrupted him at the one-minute mark. It was pretty much all downhill for the state from there.

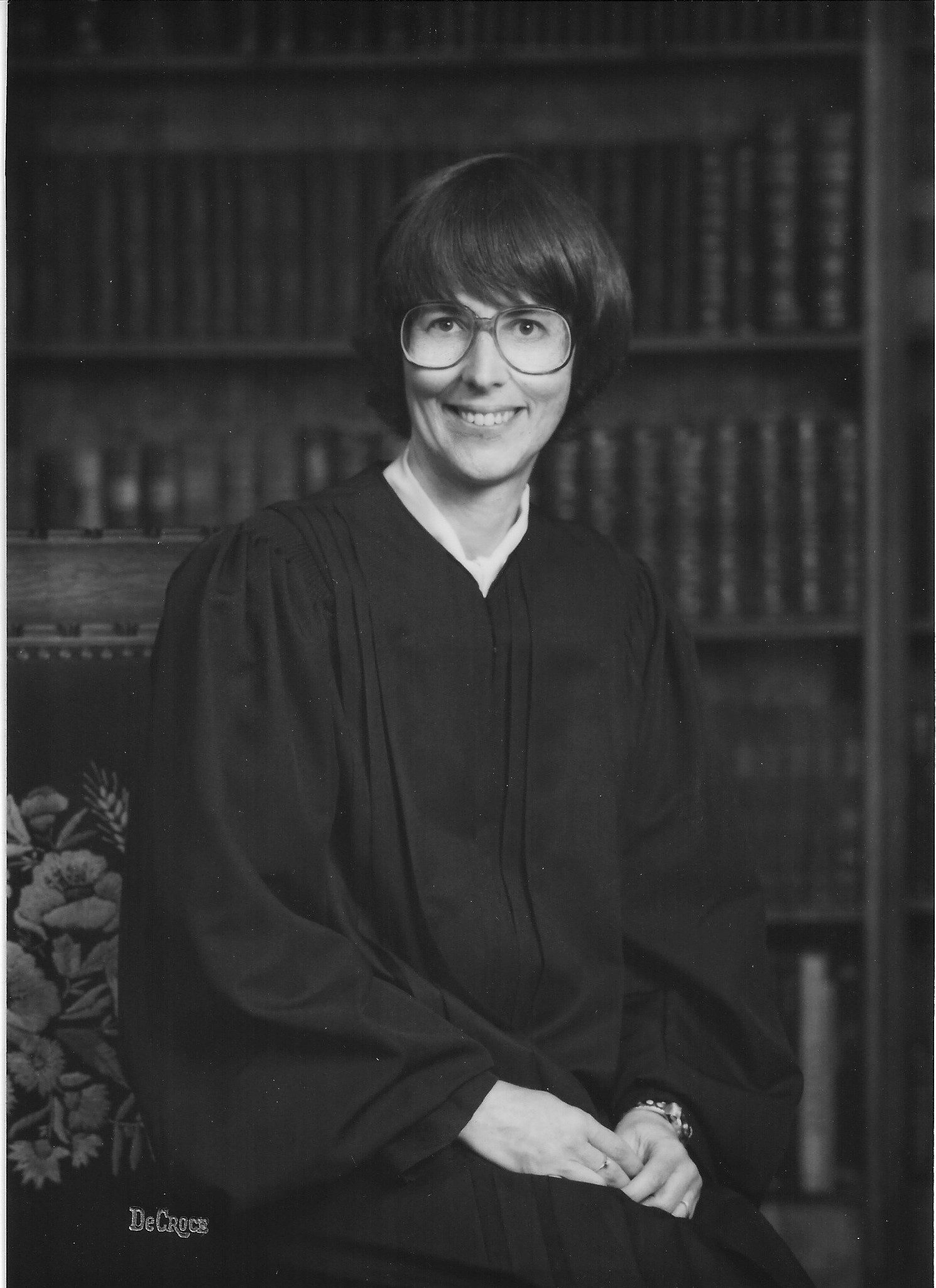

Jean Dubofsky’s official portrait as a Colorado Supreme Court justice.

Kennedy said he was not interested in the issue of allocation of power to make certain laws, essentially pushing aside the focus of Tymkovich’s argument, and dismissing for the moment the relevancy of James v. Valtierra. The justice said he wanted to focus on something else first: the fundamental question of equal protection, what Kennedy referred to as the unique and troubling way Amendment 2 appeared to threaten those protections.

“Usually when we have an equal protection question, we measure the objective of the legislature against the class that is adopted, against the statutory classification. Here, the classification seems to be adopted for its own sake,” Kennedy began. He then raised his voice and in a tone of incredulousness added: “I’ve never seen a case like this. Is there any precedent that you can cite to the court where we’ve upheld a law such as this?”

For a tick of the clock, life stopped in that courtroom.

Pat Steadman thought there might have been an audible gasp from the audience. But he wasn’t sure because, like Richard Evans, by then he was crying too.

Steadman’s night camped out on the sidewalk in order to be sitting in the audience had taken its toll.

“It was October so it wasn’t exactly warm out,” Steadman remembered. “And you don’t really sleep. There are people everywhere, protesters chanting, full blown chaos all the way around. It was the most surreal experience and by the time the sun came out, people were fighting, cutting in line, crying, screaming, praying for you. Two minutes into the oral argument I realized I was sobbing. It was partially because I was an exhausted emotional mess and partially because of what Anthony Kennedy said.” Steadman was relatively new to politics, but by then he had learned how to count votes. “I knew then that Kennedy would be our fifth vote.”

Tymkovich tried to explain that the case of James was relevant but Kennedy would have none of it. No, the justice said. That was a very different case. “The whole point of James was that we knew that it was low income housing and we could measure the need, the importance, the objectives of the legislature to control low cost housing against the classification that was adopted,” Kennedy said. “Here the classification is adopted for its own sake . . . adopted to fence out, in the Colorado Supreme Court’s words, the class for all purposes and I’ve never seen a statute like that.”

Soon Justice Sandra Day O’Connor spoke up, the tone of her questioning suggesting even less patience with Tymkovich. “How do we know what it means?” she asked a number of different times. “The literal language would seem to indicate, for example, a public library could refuse to allow books to be borrowed by homosexuals and there would be no relief from that, apparently.” He tried to explain that might not be the case, but O’Connor challenged his answer, interrupting and repeating her concern that the meaning just wasn’t very clear.

Soon it was Justice Ginsburg’s turn to reinforce concerns over the potential breadth of the amendment. With this amendment, it appears that it means “everything,” Ginsburg said. “Thou shalt not have access to the ordinary legislative process for anything that would improve the condition of this particular group... and I would like to know whether in all of U.S. history there has been any legislation like this.”

Jean felt her whole body begin to relax when Kennedy first interrupted Tymkovich. “He was our fifth vote and if he was asking as his first question ‘Has there ever been a law like this?’ I thought, well, we might just have won our case.” By the time Justices O’Connor and Ginsburg were through with their initial questions, it began to look like a rout. But only for a moment.

Justice Antonin Scalia then stepped in and tried to take the questioning in an entirely different direction, suggesting confusion over whether or not the subject of the amendment was sexual orientation or sexual conduct. If it was all about conduct, then it would be perfectly constitutional, he said, since many state laws criminalize a range of such behaviors. Tymkovich and Scalia bantered back and forth and together managed to either confuse or obfuscate whether the amendment spoke to more than conduct. This discussion clearly annoyed other justices who were trying to break into the conversation. And it annoyed Jean. “The amendment was clear. It had both words, orientation and conduct, in the language.”

Justice Ginsburg and Justice David Souter managed to elbow their way back into this debate. An aggravated Souter suggested that Tymkovich was possibly misleading the court or, at the very least, inaccurately characterizing the amendment. He went on at some length as did Justice Ginsburg, eating up the state’s precious allotted time.

And so it went. Tymkovich’s oral argument had been hijacked by the justices, one quickly taking the floor after the other, sometimes talking over the other, asking long questions that were as much making arguments as asking questions, often with one justice answering the question of another. “There was a point at which it seemed like Tim had literally taken a step back from the podium,” Jean said. “The justices were just arguing among themselves and not really looking to him for anything.”

Jean took no pleasure in seeing the justices batter the solicitor general. As she had experienced occasionally to her benefit in the past, rough treatment sometimes was meant to give judges cover so that later they would appear more even-handed when they voted for the side they had previously criticized so harshly. If not that, it surely meant that they were in a feisty mood, and her turn for battering would come soon enough.

Boulder’s Daily Camera on May 21, 1996, announced the U.S. Supreme Court’s verdict overturning Amendment 2. The city’s mayor, Leslie Durgin, had attended the Court proceedings in person.

When Tymkovich was finally able to wedge a request to save the remainder of his time for rebuttal into the back-and-forth between justices, all of ninety seconds remained. Chief Justice Rehnquist thanked him, then directly turned to Jean. “Ms. Dubofsky, we’ll hear from you.”

Jean opened with the standard salutation, “Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the court.” Unlike Tymkovich, however, her voice was quite small and quiet, without gusto or strength, not a voice exuding confidence or command. Part of it may have been nerves, but it was also just her way. She had learned very early on that a quieter voice often invites more attention. As people have to strain to hear, they have to concentrate more.

She began as a teacher might, laying out the day’s lesson, in the same manner that had served her well in other courtrooms. “Let me begin with how Amendment 2 should be construed and then discuss how our legal theories relate to its unique combination of breadth and selectivity.”

“Amendment 2 is vertically broad,” she continued, “in that it prohibits all levels of government in the State of Colorado from ever providing any opportunity for one to seek protection from discrimination on the basis of gay orientation.”

If some expected a shift in the justices’ behavior from the leaning forward, jockeying attempts to elbow themselves into the debate, cutting their colleagues off as they waited for their chance to jump in, it was not to be. Barely twenty seconds had elapsed when Chief Justice Rehnquist interrupted, stopping Jean before she had the chance to explain the second half of her description, the “selectivity” part. Rehnquist’s question was followed immediately by one from Justice Anthony Kennedy. Then another justice and another. The justices were not in the mood to sit back and allow Jean to make her arguments, and they gave her no more time to answer than they had given Tim Tymkovich. They bombarded her with question after question.

When she was allowed to answer, she consistently provided a brief “yes” or “no” statement, often quickly following up with a “but.” But it doesn’t matter because even without that, it is unconstitutional. But whether that were found to be true or not is immaterial to the constitutional questions. But that particular interpretation of the amendment is not necessary for this Court to find that Amendment 2 is unconstitutional.

With that series of “yes or no, but” responses, Jean managed to accomplish something the solicitor general was unable to do: provide clear and succinct descriptions of what the amendment meant and didn’t mean. With each answer she took particular care to go to the heart of the unhappiness that Justice Stephen Breyer and others exhibited over the lack of clarity about what policies or laws the amendment did or did not allow. At one point, when Jean stated that the amendment’s prohibitions clearly did include a certain type of policy, Breyer stopped her. “Well, what do we do when the counsel from the other side [is] saying it doesn’t?”

Jean could have taken the bait and allowed it to become “he said,” “she said”; or she could have directly accused Tymkovich of either dissembling or simply being wrong. But she did neither. Her description of what the amendment prohibited, she said, was not her interpretation, but the exact language of the Colorado Supreme Court in their written opinion.

“And where, exactly, did the Colorado Supreme Court say that?” Scalia, the “doubting Thomas” of the group, asked, clearly not persuaded that Jean’s answer was factually correct.

Jean didn’t miss a beat. With barely a downward glance, she answered: “It says that on page B dash 3, D 24, and D 25.” It was her practice to handwrite page numbers from the briefs and appendices in the margin next to each key argument listed on her one-page typed outline. She almost never was asked, but it was always one of the last things she did the night before an oral argument. Just in case.

On these pages, Jean told the justices, the Colorado Supreme Court provides examples of protections that states and cities and government agencies would be precluded from enacting under the amendment.

Like dutiful students in a classroom, all of the justices simultaneously began to flip through their notebooks, trying to find the right page, whispering to one another or asking Jean to repeat those page numbers.

“Where?” “No, not that page.” “E 25. Or is it D 25?” “In the white appendix?” “D as in ‘Does’?” asked Chief Justice Rehnquist. “D as in ‘David,’ or yes, D as in ‘Does,’” Jean answered. For a moment, the queries were all regarding which page and which paragraph. The sights and sounds of nine justices searching through their notebooks were a bit comical. Eventually they would all find the right pages.

Justice Scalia flipped through his pages like everybody else. “B 3? Where does it say that on B 3?” Scalia read a few sentences and, almost gleefully, announced that he didn’t find what Jean said he’d find.

Jean pointed out politely that he needed to go to the first sentence above what he’d just read. Scalia bypassed acknowledging her correction and continued grilling Jean on other points of contention, as well as offering his own opinion, at great length, about special rights and special protections. Jean occasionally attempted to respond but realized she could not satisfy any of his concerns, finally only offering the observation that perhaps “we are having trouble with semantics.”

Attorney Jean Dubofsky gives a press conference following the Court’s decision.

Justice Souter interrupted Scalia’s inquisition with a question of his own, which then led to more questions from other justices. But a subtle shift was unmistakable. The turning to the pages in the appendix became a figurative turning of the page in the tone and the rhythm and the content of the questions being asked. It was as if the spell of skepticism tinged with belligerence had been broken. The justices not only began to give Jean time to answer their questions, they gradually began to listen to her responses and ask related follow-up questions.

Jean’s answers seemed to reassure the justices, help simplify their decision, and reduce confusion and anxiety over the possible wider repercussions of their decision. Her intent was to persuade them that, while the impact of the amendment to cause harm was wide and broad, resolving how wide and how broad had no bearing on the constitutionality of the amendment. Even a minimum, narrow finding was sufficient to constitute a violation of equal protection, she argued.

She repeatedly used the phrase “at a minimum” to encapsulate how they could frame their analysis. At a minimum the amendment means this...or at a minimum the Colorado Supreme Court found that.... Jean’s message to the court was clear. Even if the court understands the impact of the amendment to be a small, narrow, de minimis discriminatory impact, she emphasized, that is sufficient to find it unconstitutional.

At one point, Chief Justice Rehnquist attempted to restate Jean’s argument in the form of a question. Are you saying that we “can sustain the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision overthrowing the statute by taking just what the Colorado Supreme Court said was the minimum meaning?” “Yes, that’s correct,” she responded. Soon, other justices were also using the phrase “at a minimum.”

As her time was about to come to a close, Jean was asked the final, critical question that had yet to be addressed. What about Bowers v. Hardwick, the 1986 Supreme Court ruling that sustained the Georgia law making sodomy a crime? The court did not want to touch that case; did not want their decision in Romer to be tied to that case in any way; did not want to open the Pandora’s box that attempting to reverse Bowers would entail. And Jean let them off the hook.

You don’t have to undo Bowers, she told the justices, to find Amendment 2 unconstitutional. Once again, Jean reassured the court that they need not break any previous barrier or plow new ground to rule for the plaintiffs.

With that, Chief Justice Rehnquist thanked her, the signal that her time was up. And, after thanking Colorado solicitor general Tim Tymkovich, he announced that “the case is submitted.” And that was that.

The Daily Camera of May 21, 1996, showed jubilation at the U.S. Supreme Court verdict.

That October day was not the end of the story, however. In a way, it was another beginning. On May 20, 1996, when the United States Supreme Court ruled Amendment 2 unconstitutional, it started a chain of events that over the decades has stretched the possibilities of justice and equality for the LGBT community.

Twenty years later, the ripples from Romer v. Evans continue to impact millions. Before the court ruled in that case, gays and lesbians were often fired from jobs when their sexual orientation was discovered. Zoning laws prevented homosexuals from owning homes in certain neighborhoods, and refusing to rent or sell to someone even suspected of being of being a homosexual was legal. Harassment and violence was common, with the police and the justice system often turning the other way. And sex between same-sex couples, in the privacy of their own homes, was a crime.

After Romer v. Evans, through thousands of local and state ordinances and legal decisions upheld by one high court after another, gays and lesbians have become free to live and work where they want, and free to enjoy the same protections and benefits as all citizens.

Jean Dubofsky, Boulder attorney and former Colorado Supreme Court justice, in 2016.

In 2003, in Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court ruled that the Texas law making it a crime for two people of the same sex to engage in sexual conduct was unconstitutional. In 2013, in United States v. Windsor, the Court ruled that the federal government could no longer treat married same-sex couples differently when it came to benefits available to other married couples. And on June 26, 2015, in Obergefell v. Hodges, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the right to marry was a fundamental right under the Constitution, even for same-sex couples.

Without Romer v. Evans, there likely would not have been Lawrence; without Lawrence, there might not have been Windsor. But with those three rulings it was all but inevitable that same-sex marriage would become the law of the land. And it all started in Colorado.

For Further Reading

The author’s Appealing for Justice: One Colorado Lawyer, Four Decades, and the Landmark Gay Rights Case: Romer v. Evans has just been published by Gilpin Park Press of Denver. Find Romer v. Evans trial transcripts at the Denver Public Library, Western History & Genealogy, Romer v. Evans Collection, boxes 1–4. All quotations of oral arguments are from the official Supreme Court transcript, retrieved at oyez.org/cases/1995/94-1039. A video interview with former governor Roy Romer is available at “Voices of the Law,” Duke University Law School, web.law.duke.edu/voices/.

For press coverage of the trial, see Rocky Mountain News, October 1, 1995; Washington Blade, October 6, 1995; Washington Post, October 10, 1995; and Rocky Mountain News, October 11, 1995. See also Lisa Keen and Suzanne B. Goldberg, Strangers to the Law: Gay People on Trial (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998).

More from The Colorado Magazine

Why Boulder County Courthouse is recognized for its role in LGBTQ history Many consider the Stonewall riots of 1969 in New York City to be a pivotal moment in LGBTQ history in the U.S. Fewer remember that one of the most significant events that followed happened a few years later in Boulder, Colorado.

The Queen City Denver’s Homophile Organizations from 1950-1970

From the KKK to The Proud Boys What A Forty-Year-Old Book on the Colorado Klan Teaches Us About Hate Organizations Today