Story

From the KKK to The Proud Boys

What A Forty-Year-Old Book on the Colorado Klan Teaches Us About Hate Groups Today

It’s a time of anxiety. A deadly global pandemic swept the nation, but is slowly releasing its grip. Other pressing issues—racial discrimination, immigration, crime, labor rights, and economic inequality—are all volatile political flashpoints. Americans observe each other warily (and at times with shock, disgust, fear, mistrust, and smugness), and controversial laws prop up the old social order even as technology remakes everyday life.

These are, to say the least, hallmarks of “uncertain times.” But as regrettably familiar as they are in 2021, such circumstances would have been equally familiar in 1921. We may think of the roaring twenties as the time of bootleggers and speakeasy-dwelling flappers. But we rarely think about it as a time of instability. And, not coincidentally, we rarely acknowledge the decade as the heyday of Colorado’s Ku Klux Klan. In those tumultuous years, the KKK preyed on the anxieties and fears that often accompany rapid change in order to amass stunning political power. Colorado’s Klan captured political and bureaucratic offices, including congressional seats and judgeships, as well as Denver’s Mayor’s office and the Governor’s mansion. In fact, in the middle part of the decade, more than 35,000 Colorado men belonged to the notorious white supremacist organization, and Colorado’s Klan trailed only Indiana’s in terms of the extent of its political influence.

How could this have happened in a place like Colorado? What motivated the people who joined, and where did they come from? How did Klan membership differ across the state, and what does that tell us about Colorado then and now? These are the questions animating Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado, the still-seminal study of Colorado’s Klan by historian Robert Alan Goldberg. Hooded Empire is worth a fresh read in this modern moment of rising white supremacy for the way it illuminates the individual motivations that attracted Coloradans to Klan membership in the 1920s. And in forcing us to re-examine these questions, the book is perhaps more relevant now than when it was written in 1981. After all, Goldberg’s look under the hood of the KKK offers lessons for what drives white supremacy and its expressions in every era. What’s revealed are the daily worries and fears of ordinary people, and the systemic structures that enabled a group of white supremacists to capture enormous power for a brief but harrowing period just over a century ago.

One of the features that gives Hooded Empire staying power on the bookshelf in 2021 is Goldberg’s insight that the Klan used wedge-issue propaganda to prey on social and economic anxieties among Colorado’s white Protestants. In contrast to other iterations of the Klan which exploited explicitly racial divides, Colorado’s Klan focused its divisive campaign on religious schisms to motivate its supporters. African Americans and Asian Americans together only made up a small fraction of the state’s overall population. And due to discriminatory housing policy and violent intimidation, they were mostly concentrated in Denver. The relatively small size of these communities, their intentional disenfranchisement, and their enforced concentration in small pockets of town meant that Denver’s people of Black and Asian ancestry did not pose enough of a threat to a social order dominated by white Protestant men to be effective wedge-issue bogeymen outside of the capital city. So anti-Black and anti-Asian messaging failed to galvanize much Klan support around the state. Similarly, though Denver did have a relatively large Jewish population that was the target of anti-Semitic harassment and intimidation from local Klan members, Denver’s Jews were initially concentrated in a small enclave along West Colfax and did not significantly challenge the state’s social and political order. Instead, Goldberg’s research reveals that it was the Catholic church and its adherents—many of whom came from Hispanic families—who found themselves the main subject of the Colorado Klan’s most virulent and concentrated discrimination.

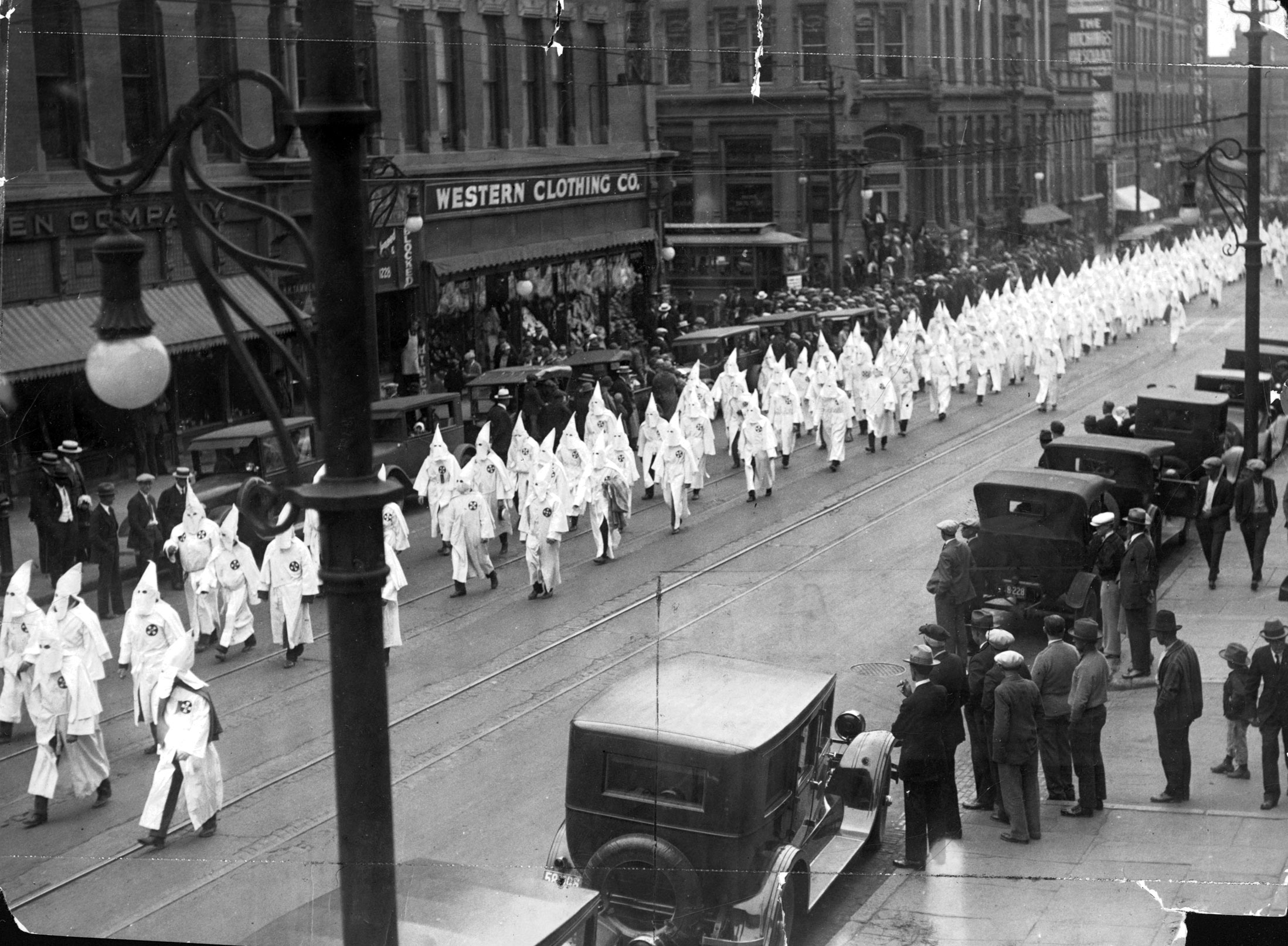

Anti-Catholic sentiment ran high during the 1920s on fears that the Pope and his church did not respect American laws, and had crafted a nefarious plot to interfere in American politics. Not for the first time in American history (and certainly not for the last), Catholics were seen as agents of a foreign power and accused of putting their loyalty to the Pope over their loyalty to Uncle Sam. KKK marches across the state featured signs proclaiming that the Klan was “For Restricted Immigration” and pledging to ensure that America is safe for Americans. Such discriminatory messages resonated in communities like Denver, Pueblo, and Cañon City with growing populations from predominantly Catholic countries like Mexico, Italy, and Ireland. In one of the book’s most fascinating chapters, Goldberg explores how the Southern Colorado Klavern exploited religious difference to great success in Pueblo, but failed to gain significant ground in Colorado Springs. The reason for these divergent experiences was that the relative lack of ethnic and religious diversity in Colorado Springs meant Klan messaging about a vague Catholic or racial menace fell flat. In contrast, southern Colorado towns had lots of residents who practiced Catholicism and whose skin color made them obvious targets for discrimination. As a result, divisive Klan messaging was more successful in driving a wedge between community members. White Protestant residents in southern Colorado towns welcomed the Klan’s organizing activities and enrolled in the KKK with such gusto that a silent march of three-hundred-fifty Klansmen proceeded through Walsenburg in 1924. Even in silence, they sent the clear message that the Catholic faith and its adherents were unwelcome in Colorado.

Though anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic suspicion and racial discrimination certainly helped drive Klan membership, it was Prohibition (or rather, those flouting the dry laws) giving the Klan one of its most powerful recruitment tools. Statewide Prohibition came in 1916, but Colorado had a particularly strong dry movement with deep connections to Protestant faith leaders predating the state’s founding in 1876. Several legislative efforts at statewide Prohibition failed in the intervening years, but Colorado’s dry campaigners eventually succeeded in banning commercial alcohol production in 1916—four years before the rest of the nation went dry in 1920. Yet for all the state’s Prohibition ferver, the challenge of enforcing the measure proved too much for undermanned and under-equipped local police. The sudden and dramatic uptick in crime resulting from bootlegging and moonshining was a very public source of daily anxiety and fear. Making matters worse was the fact that Italian American organized crime syndicates dominated Colorado’s black market alcohol trade at the time. The Klan made sure the public blamed Italian Americans (and, to a lesser degree, people of Hispanic descent) for shocking Prohibition-related violence, and illegal moonshine for what the Klan said was an erosion of American values. KKK propaganda made good use of the salacious headlines resulting from a string of brutal bootlegger murders to position themselves as vigilante Prohibition enforcement agents, and played up bootleggers’ foreign origins to deepen their argument that hooch-making immigrants were undermining American laws. Public perceptions that the cops weren’t up to the job of confronting a crime problem that was rapidly getting out of hand gave the Klan’s law-and-order messaging a pretense of benevolent legitimacy, enabling it to openly seize control of statewide and local levers of power.

The Klan came to Colorado in 1921 and immediately set about organizing new members. Kleagles (the KKK’s term for its recruiters) kept eight dollars of the ten-dollar Klectoken (initiation fee) paid upon signing up—a significant amount of money and a powerful enticement to continue recruiting new members. Those who did sign up came from all economic classes. Doctors and lawyers, laborers and servants, all enthusiastically joined. By June 1921, thanks in part to high profile KKK-led liquor raids that targeted Italian and Hispanic Coloradans, the Klan felt that it had enough clout to announce its presence in The Denver Times: “We are a law and order organization assisting at all times the authorities in every community in upholding law and order. Therefore we proclaim to the lawless element of the city and county of Denver and the state of Colorado that we are not only active now, but we were here yesterday, we are here today, and we shall be here forever.” Though met with outrage and resistance from many in Denver’s marginalized communities, a significant portion of white Protestants in Denver barely questioned the Klan’s supposed noble intentions or its necessity, and continued joining the Klan in droves. In 1922, more than two thousand hooded men gathered for an initiation ceremony in Estes Park. Membership continued to climb throughout 1922 and 1923, and Goldberg points to the physical movement of non-white and non-Protestant people within Denver during the mid-twenties in particular for helping to drive Klan enrollment. Contact with those who prayed or looked different, it seems, was the prime factor in driving white Protestants to the Klan.

Colorado’s Realm was headquartered in Denver, and from the beginning, local Klavern leaders took their political cues from Colorado’s Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke. A shadowy physician with an infectious personality, Locke commanded loyalty from some of Colorado’s most significant politicians. Colorado Governor Clarence Morley was one of Locke’s most ardent supporters, and the Klan counted on Denver Mayor Benjamin Stapleton to enact its discriminatory and white-supremacist agenda in the capital city. Goldberg follows Stapleton’s rise to office in 1923, noting that he was initially hesitant to appoint a Klan-approved chief of police. But after facing down a recall election sparked by revelations of Stapleton’s Klan affiliations, the Mayor fully embraced the Klan’s agenda. William Kandlish was duly appointed Police Chief of Denver, and went about recruiting Protestant police officers to join the KKK. In this way, Locke was able to turn the Denver Police into an arm of the KKK tasked with harassing, arresting, beating, and generally making life tough for anyone in Denver who wasn’t white and Protestant.

But the Klan’s impressive ability to intimidate others, recruit members, and get them elected to political office was not matched by legislative success. Throughout the 1920s, Klan members in political office introduced dozens of new discriminatory proposals, but few became law. Prohibition was becoming more familiar and bootlegging violence was in decline. With a stabilizing crime rate, public sentiment was turning against the Klan. Voters were suspicious of elected officials with Klan loyalties, and as the KKK’s white supremacist agenda came into sharper focus, support rapidly drained away. His legislative efforts in tatters, and facing investigations for tax fraud, John Galen Locke lost his grip on his members. In a final embarrassing devolution, Locke was driven from the Klan in 1925. From there, Goldberg notes that the Klan lost ground almost immediately. Stapleton fired Locke’s hand-picked chief of police, opened new investigations into Locke’s dealings, and as a result KKK membership steadily declined throughout the remainder of the decade. The picture Goldberg paints is one of an organization that excelled at using divisive issues and conspiracy theories to gain members and influence, but one that was unable to translate that success into legislative victories due to the odious nature of its white supremacist and anti-democratic agenda.

Goldberg closes his book by returning to the question he poses at its beginning: who was in the Colorado Klan and why did they join? For Goldberg, the answers to these questions are as diverse as each Klan member. Hooded Empire shows us that the KKK of the 1920s represented a too-familiar moment when perceived conspiracies and real challenges to the established political and social order galvanized a white supremacist movement that was willing to overlook its own hypocrisy and anti-democratic values.

At times, the author’s academic distance from his subject almost seems to sympathize with Klan members’ motivations. Goldberg’s focus on using census data and deep dives into social conditions of the time also tend to remove the reader from the more violent and despicably racist actions the Klan undertook. Furthermore, modern readers will notice that almost all of the actors in Goldberg’s book are Klan members, while moments of resistance get only brief mentions. Goldberg gives tantalizing glimpses of Black students demonstrating against segregated high school dances or protesting against Denver theaters showing the KKK propaganda film Birth of A Nation, but rarely follows up on those moments with detailed discussion. Nonetheless, Goldberg’s mission to humanize the Klan—to help us understand how each Klavern tailored its messages to local concerns—gives us a window into the times that too often reveals uncomfortable truths about twenty-first-century America. Reading the book in 2021, it’s impossible not to draw parallels to our own moment of baseless conspiracies and resurgent white supremacy embodied by The Proud Boys and other hateful organizations. White hoods and cross burnings may not be a prominent feature of twenty-first-century America, but insurrections and conspiracies show us that the fears and prejudices animating those symbols of white supremacy in the 1920s are still alive today.

Returning to Hooded Empire forty years on reminds us that the people under the robes and wearing the horns are human beings. Though their warped ideology is never acceptable, their motivations and fears are complex, and to them, very real. By understanding that members’ day-to-day concerns reflected their reasons for joining the Klan, Goldberg’s book opens a timeless window into the conditions that push people across the boundary separating private prejudice and organized hate. One hundred years later, the Klan’s rise and fall offers a lesson for our own uncertain times, and asks us to consider how we want future Coloradans to write about what we did in this moment.

More from The Colorado Magazine

“Curse of a Nation” Denver Black Newspapers Respond to the Debut of “Birth of a Nation”

Don’t Leave Home Without Your Green Book The Black Travel Experience in Colorado During the Jim Crow Era

Left on the Field: Colorado’s Semi-Pro and Amateur Baseball Teams