Story

Were They Mexicans or Coloradans? Constructing Race and Identity at the Colorado–New Mexico Border

Emerging Historians Award

What does it mean to be a Coloradan? A connection to snow-capped, Rocky Mountain peaks and imposing, river canyon walls is often part of the portrait, even for those who migrate to growing cities along the Front Range. For Coloradans on the Eastern Plains, a relationship to agricultural landscapes and rural communities remains important too. A diverse heritage also shapes Colorado identity—one that fuses Colorado’s American history with the state’s Spanish, Mexican, and Indigenous pasts. Currently, this cultural identity grows more expansive as Colorado continues to experience an influx of Americans from across the United States and immigrants from around the globe.

These two characteristics—a powerful connection to nature and a diverse cultural inheritance—converge in the San Luis Valley, a small, intermontane park in southern Colorado where the state’s complex past and multicultural identity are made manifest beneath a sublime, mountainous backdrop. Today, the San Luis Valley is a Colorado landscape. But it almost wasn’t.

This 2016 vista of Alamosa and Saguache counties in the San Luis Valley includes today's Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve.

*Editor’s note: This essay is the Best Overall Essay winner in the 2019 Emerging Historians Award. The Emerging Historians Award is a program of History Colorado’s State Historian’s Council. Find entry guidelines for the 2023 contest—with a submission deadline of June 1, 2023—at https://www.historycolorado.org/emerging-historians-award.

“Map of Colorado Embracing the Gold Region,” 1862, drawn by Frederick J. Ebert under the direction of Governor William Gilpin and published in Philadelphia by Jacob Monk.

In the spring of 1870, the San Luis Valley’s territorial identity was up for debate. New Mexico territorial representative Jose Francisco Chaves had recently introduced congressional legislation that would redraw the boundary line separating the Colorado and New Mexico territories. Chaves aimed to move the territorial boundary from its existing location at the 37th parallel to the northern, 38th parallel and to annex the entirety of the San Luis Valley into New Mexico in the process. Under Chaves’s bill, Costilla County and Conejos County, the local administrative units governing most of Colorado’s portion of the San Luis Valley, would become part of New Mexico.1

For Chaves, integrating Costilla County and Conejos County into the New Mexico Territory made perfect sense. Nuevomexicanos—a cultural group of Hispanic peoples residing in the (formerly Mexican) New Mexico Territory—made up the majority of the San Luis Valley’s settler population in 1870.2 By the 1860s, however, Euroamerican immigrants began settling alongside the valley’s Nuevomexicano communities, a sign that the landscape’s Nuevomexicano identity was beginning to give way to a more culturally diverse future.3 When Chaves created legislation that would annex the San Luis Valley into the New Mexico Territory, he made an implicit cultural claim to the region’s Nuevomexicano legacy.

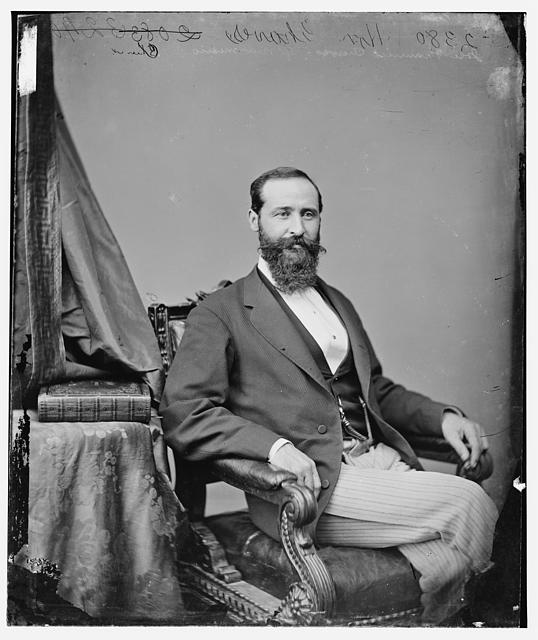

New Mexico territorial representative Jose Francisco Chaves, shown here around 1865, introduced legislation to redraw the boundary between the Colorado and New Mexico territories. Under Chaves’s bill, the San Luis Valley would have become part of New Mexico.

And it was hardly the first time. The Colorado–New Mexico border, as historians Virginia Sánchez and Philip Gonzales have suggested, had been central to the ongoing “demographic dismemberment” of Nuevomexicanos who resided in Colorado after the 1861 creation of the territory yet maintained ancestral and political ties to the New Mexico Territory.4 The territorial boundary, according to the Chaves Bill and preceding conflicts over the territorial status of the San Luis Valley, separated more than the New Mexico and Colorado territories. At stake in its location was a geographic boundary that separated Mexicans and Americans.5

When the Chaves Bill emerged in Washington, D.C., the residents of the San Luis Valley faced a choice: would they be New Mexicans or Coloradans? As communities throughout the valley debated Chaves’s proposal, they questioned what it meant to be, as they called themselves, “citizens of Colorado.”6 Outsiders weighed in as well, and, before long, public debate over Chaves’s legislation transformed into an exploration of nineteenth-century Coloradan and American identity. Though the bill eventually failed, arguments traded in the regional press made clear that Nuevomexicanos could never fully claim an identity as citizens of Colorado on account of cultural differences that were increasingly hardening into racial distinctions.

Nuevomexicanos in the San Luis Valley may have entered the border conflict alongside their white neighbors as citizens of Colorado, but they emerged as Mexicans.

The conflict over the territorial membership of Costilla County and Conejos County illuminates a western landscape in a state of cultural flux. In the mid-nineteenth century, rumors of mineral wealth buried in the San Juan Mountains fueled Euroamerican migration to the San Luis Valley. By the late 1860s, however, the purpose of Euroamerican immigration to Colorado changed; Euroamericans no longer came strictly as profiteering interlopers in a Nuevomexicano landscape.7 Instead, they traveled as settlers keen on transforming Colorado into a distinctly American space. The Chaves Bill offered Euroamerican settlers an opportunity to Americanize—or, in this case, whiten—the Colorado Territory. Within this Americanized Colorado, Euroamericans attempted to transform Nuevomexicanos into racialized Mexicans. Nuevomexicanos experienced this transformation through a process of what historian Kunal Parker describes as being “rendered foreign” within a political territory where they had assumed themselves to be citizens.8 Nuevomexicanos in the San Luis Valley, however, resisted the expulsion from both the Colorado Territory and its body politic by claiming an identity as citizens—a rhetorical position which revealed that at least some non-white Coloradans believed that citizenship rights might protect them from racial subordination in the new territory.

As New Mexicans and Coloradans debated the merits of the Chaves Bill, they imbued the Colorado–New Mexico border with a racial identity that distinguished between white and nonwhite, and American and foreign, populations within Colorado. The conflict over the 1870 Chaves Bill helped to redefine Colorado as an American territory, and through a brief but contentious public debate, Coloradans and New Mexicans constructed race and citizenship identity together at the Colorado–New Mexico border.

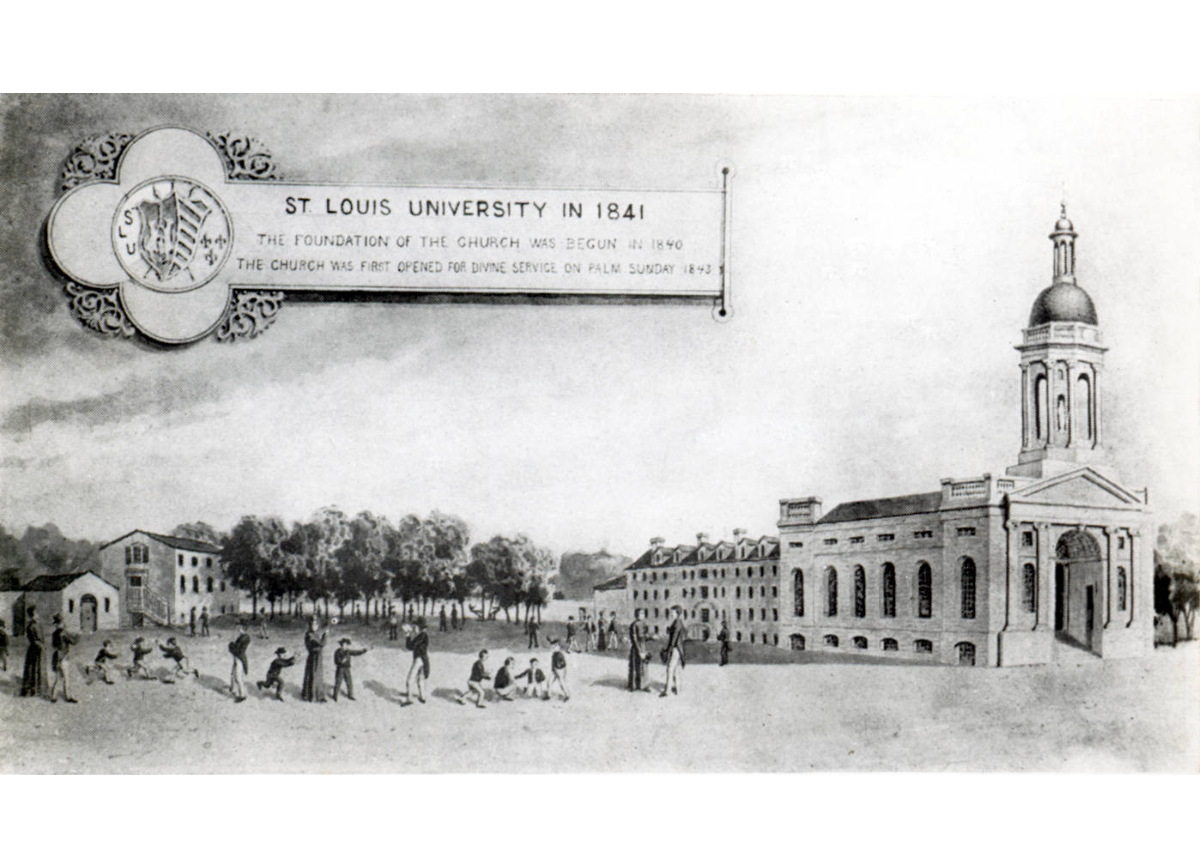

Born to an influential New Mexico family, Jose F. Chaves attended St. Louis University (depicted here as it appeared in 1841), a Catholic boarding school in St. Louis, Missouri.

In light of how borders currently inform American public discourse and national identity, the history of the 1870 conflict over Colorado’s southern border and Coloradan and American identity suggests that, in the past as in the present, race has often defined what it means to be immediately recognized as an American citizen.9

José Francisco Chaves was not an American by birth, having been born in New Mexico before the territory was annexed into the United States at the conclusion of the U.S.-Mexican War. Born on June 27, 1833, in Los Padillas, New Mexico, Chaves began his life as part of an influential Nuevomexicano family. Unlike poorer Nuevomexicanos in the region, however, Chaves immersed himself in elite circles from a young age when he began attending St. Louis University, a Catholic boarding school in St. Louis, Missouri, in the 1840s.10 As a member of the elementary class, Chaves went by the first name of Francis, perhaps in an effort to fit in with his American peers.11

Chaves’s school records show that by the time he began boarding at St. Louis, his family had relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where they cultivated political and economic influence in the region.12 After Chaves returned to New Mexico in 1852, he found that his American education would prove useful in his political career.13 While his facility with Spanish helped him interact with the Nuevomexicano community in Santa Fe, the knowledge of English he gained from his American education helped him to support his neighbors in the venue that would determine their territory’s future: the United States Congress.

Chaves served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives as New Mexico’s territorial delegate. He first ran successfully in 1864 and then ran again in 1866, losing to General Charles Clever.14 Chaves ran for the third time against Clever in 1868, but the contest embroiled him in electoral controversy. At first, Clever appeared to have won the election. But H. H. Heath, Chaves’s attorney and Secretary of the New Mexico Territory, declared Chaves victorious, accusing Clever of election fraud in the process.15 As the Santa Fe press waffled between supporting Chaves, accusing him of fraud, and implying that his family connections enabled him to influence the election’s outcome, Heath certified Chaves’s victory.16 By the close of 1869, Chaves departed New Mexico for a second and hopefully more successful tenure as its territorial representative.

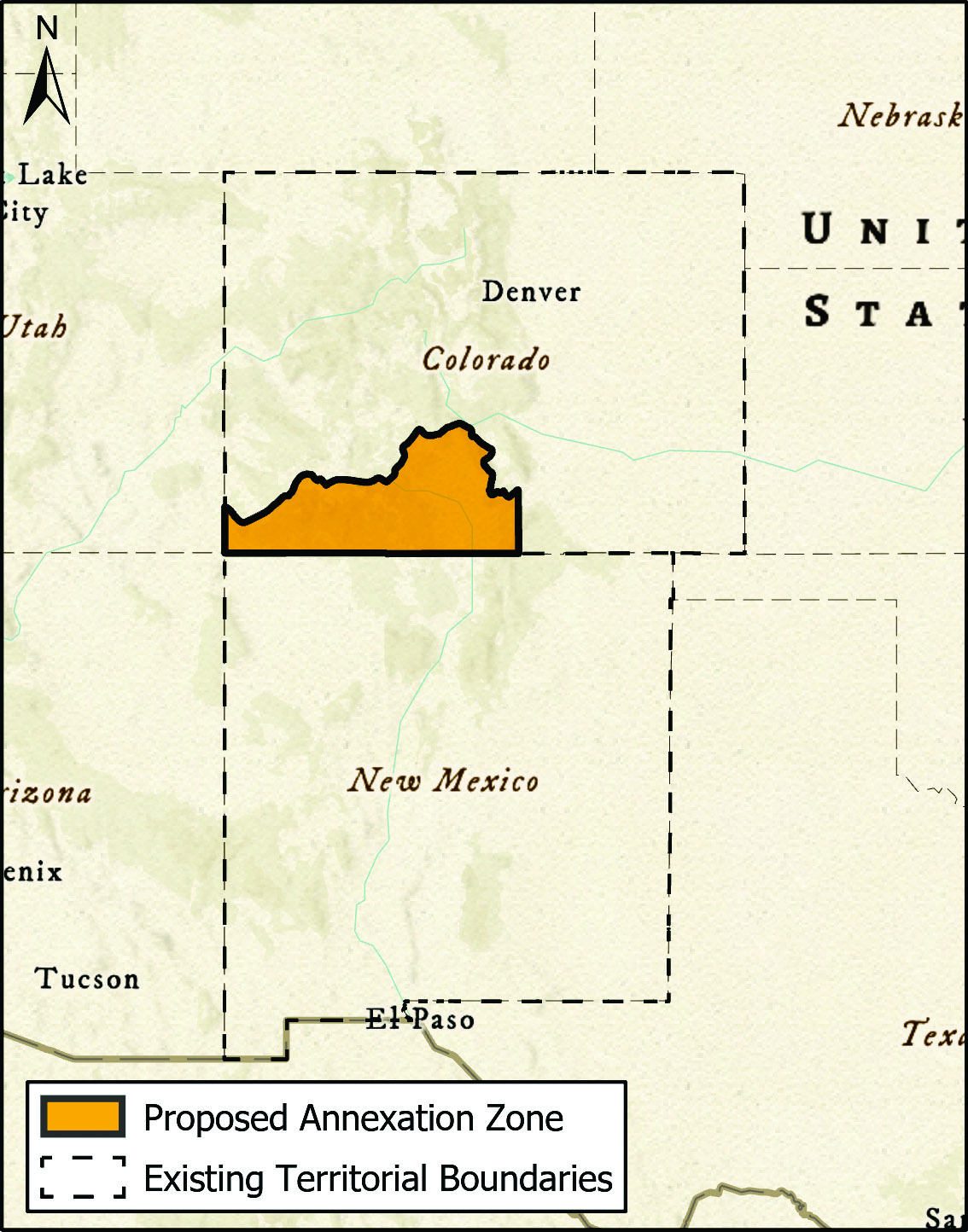

Under Chaves’s proposal, most of southwestern Colorado would be annexed into New Mexico. In total, this area contained almost 13,000 square miles of land and 4,587 Coloradans. Map and annexation zone boundaries based on Frederick J. Ebert’s “Map of Colorado Embracing the Gold Region,” 1862.

As a congressional representative, Chaves did not simply concern himself with Nuevomexicano interests within the New Mexico Territory. Although statehood remained paramount among Chaves’s goals in Congress, he also sought to reclaim the territory’s lost Nuevomexicano population in the San Luis Valley. The valley is one of Colorado’s four inter-mountain, high-altitude grasslands and covers an area of about 150 miles long by 50 miles across, a small, 15-mile-long portion of which resides in New Mexico. Cradled by the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the east and the San Juan Mountains to the west, the valley’s physical geography produces a north-south orientation that linked nineteenth-century valley populations to southward communities at Taos and Santa Fe.17

Given the imposing and generally inaccessible slope of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, valley denizens remained remote from Denver and other American settlements to the north throughout the mid-nineteenth century.18 The Colorado–New Mexico boundary line, drawn along the 37th parallel, bisected the San Luis Valley and politically severed Nuevomexicano communities in the north from their neighbors to the south.19 But arbitrary latitudes scarcely reflected settlement patterns and the valley’s cultural geography. As the Chaves Bill suggested, redrawing the border to annex the San Luis Valley into the New Mexico Territory offered a cartographic solution to a geographic problem.

Congressional legislation, however, only formed one dimension of Chaves’s efforts to reincorporate the San Luis Valley into New Mexico. He also lobbied for support among the valley’s Nuevomexicano communities. By 1870, Nuevomexicanos had lived in Costilla County and Conejos County for quite some time. Their settlement efforts began in the 1820s, but Ute bands who controlled the San Luis Valley repelled early Nuevomexicano advances. By the 1840s, permanent Nuevomexicano settlements emerged in the southern part of the valley. These early communities included Los Rincones, populated by settlers led by Tata Atanasio Trujillo (who enjoyed cordial relations with the Utes), and Costilla, founded by settlers led by Carlos Beaubien, who had acquired title to most of Costilla County through the Spanish-Mexican land grant system.20 With time, Nuevomexicano populations expanded, reaching 1,452 in Costilla County and 2,456 in Conejos County by 1870.21 Although American settlers and soldiers arrived in the 1860s, Nuevomexicanos retained an overwhelming demographic majority in the valley throughout the 1870s.22

Chaves’s public campaign for annexation centered on appeals to the valley’s Nuevomexicano communities. In January 1870, Chaves dispatched Seledonio Valdez and Manuel Sabino Salazar from the New Mexico Territory to represent his case for annexation to communities in the San Luis Valley. In Conejos County, Valdez and Salazar engaged with valley Nuevomexicanos and lobbied for petition signatures in support of the Chaves Bill.23 As Juan B. Jaquez, a resident of Guadalupe in Conejos County, reported, Valdez and Salazar “urged in the strongest language the immense advantages to be gained by annexation to New Mexico.”24 According to Valdez and Salazar, “fuller justice and less taxation” as well as “laws in the ‘mother tongue’” were among the benefits that annexation offered to the San Luis Valley’s Nuevomexicanos.25

It is certainly possible that Nuevomexicano communities desired stronger legal protections, especially from vigilantes.26 In May, just a few months after Salazar and Valdez’s trip to Conejos County, local Utes discovered the body of Jose Roderigo, whom authorities had confined in the county jail based on his “reputation of being a horse and cattle thief.”27 Heavy rains had swept away the sand covering Roderigo’s body, revealing a hole “such as would be made by a pistol ball” in the side of his head.28 As Roderigo and others fell victim to frontier violence in the San Luis Valley, Valdez and Salazar’s offer of “fuller justice” under New Mexican rule may have grown more appealing to valley communities.29

In addition to offers of tax relief and legal protections, Valdez and Salazar also made an explicitly demographic appeal to the valley’s Nuevomexicanos. Annexation, Valdez and Salazar claimed, would produce a “similitude of race” in the San Luis Valley.30 Although the valley floor was not a strictly segregated landscape, towns in the San Luis Valley tended to host either a predominantly Nuevomexicano or Euroamerican population.31 As the clustering of Nuevomexicano and Euroamerican populations and the racialized overtures of Valdez and Salazar suggest, some nineteenth-century westerners viewed Nuevomexicanos and Euroamericans as distinct groups.

And, as some Coloradan responses to the Chaves Bill indicate, the possibility of “racial similitude” made the Chaves Bill desirable for white Americans as well.32

Remnants of the Plaza at Costilla, just a short distance south of the Colorado-New Mexico border.

As Coloradans considered the role of Nuevomexicanos in the territory’s future, they confronted a peculiarity of the nineteenth-century American racial hierarchy: Mexicans were legally white but often racialized as nonwhite.33 Mexicans’ legal whiteness stemmed from two documents: the Naturalization Act of 1795 and the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The Naturalization Act of 1795 linked whiteness to citizenship in the American legal system, stating that “any alien, being a free white person, may be admitted to become a citizen of the United States.”34 The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted Mexicans who remained in newly American territory the option to “either retain the title and rights of Mexican citizens or acquire those of citizens of the United States.”35 By extending naturalized citizenship rights, which were only available to free white persons in 1848, to Mexican nationals, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo defined Mexicans as legally white. Citizenship rights, however, did not automatically produce claims to American identity. Some Coloradans communicated as much when they entered the debate over the Chaves Bill and argued that racial differences disqualified Mexicans from becoming Americans.

For Baden Weiler, the distinction between Mexicans and Americans was all too clear. In March 1870, Weiler, who lived in the northern San Luis Valley, used the editorial platform of Denver’s Rocky Mountain News to inform the public that Mexicans were certainly not Americans.36 Weiler insisted that the Chaves Bill provided an opportune moment to remove the Mexican population from Colorado. Much like Valdez and Salazar’s claim that annexation would lead to “racial similitude,” Weiler indicated that the Chaves Bill would result in a new racial geography that contained only desirable, or, in Weiler’s view, white, communities within the Colorado Territory.37 Although Weiler accused the San Luis Valley’s Nuevomexicano populations of tax delinquency and emphasized the incompatibility of their Catholicism with the territory’s Protestants, his most forceful support for the Chaves Bill surfaced in racial arguments.38 In overtly racial terms, Weiler asked of his readers: “Why should the citizens of Colorado longer detain this mongrel race within their borders?”39 According to Weiler, Nuevomexicanos would never truly be Coloradans or Americans on account of racial differences.40

Weiler was not alone. Throughout the 1860s and ’70s, whites consistently racialized Nuevomexicanos as a nonwhite, non-Coloradan group. In the San Luis Valley, white Americans commonly explained Nuevomexicanos’ racial difference through their role in the valley’s development. Ferdinand V. Hayden, a U.S. Geologist who conducted multiple surveys of the New Mexico and Colorado Territories in 1868 and 1869, suggested that the Southwest’s economic potential remained untapped due to the “shiftless, slovenly manner characteristic of the Mexicans.”41 Others, such as the anonymous author of a “character sketch” of a Mexican teamster, explained Nuevomexicano difference in ethnological terms, claiming that Nuevomexicanos were the “mongrel offspring of the Aztec, the Indian, and the Negro.”42 Nuevomexicanos, at least in the imagination of Weiler and other white Americans, qualified only as obstructions to progress in the Colorado Territory.

The Commandant's Quarters of today's Fort Garland Museum & Cultural Center, built in 1858. A site of History Colorado, the museum (including five of its original adobe buildings) is where you can go to explore the history of Colorado's San Luis Valley.

Alongside public debate over the Chaves Bill, Weiler and his fellow Coloradans linked Nuevomexicanos’ outsider status to an 1870 proposal to prohibit the territorial government from printing documents in any language other than English.43 As Gonzales and Sánchez have shown, the printing of government documents in Spanish was hotly contested in territorial Colorado and, like the debate over annexation, functioned as a proxy for debates of the place of Nuevomexicanos in the Colorado Territory.44 Nuevomexicanos’ use of Spanish, Weiler claimed, not only marked them as culturally different from Colorado’s English-speaking population, it also strained the territory’s financial resources. Weiler cited the cost of producing government documents in Spanish at $5,840. The Colorado counties containing sizeable Nuevomexicano populations only generated a tax revenue of $3,792.92, which, according to Weiler, hardly justified the printing costs. Weiler hoped the Chaves Bill would bring desirable demographic change and, at the same time, would keep taxpayer monies from flowing to Nuevomexicanos whose presence “seriously retards the progress and advancement of this section of our territory.”45

For many New Mexicans and Coloradans, the Chaves Bill appeared to be an obvious solution to a cultural and racial problem. Reuniting the San Luis Valley with the New Mexico Territory offered Chaves an opportunity to prove his support for the region’s Nuevomexicanos and promised Weiler and other Coloradans the white, settler state they desired to build in the American West. If Chaves succeeded, Weiler and others believed that Colorado might finally contain a racially desirable population. As Salazar, Valdez, and Weiler saw it, “racial similitude” would bring social harmony and progress for white and Nuevomexicano communities alike.46 Local communities in the San Luis Valley, however, begged to differ.

On February 14, 1870, the Costilla County courthouse transformed into a meeting hall where Nuevomexicano and white Costillans gathered to weigh the merits of the Chaves Bill. Community organizers decided that the bill held little advantage for Costilla County and established a committee to conduct a public campaign against annexation. The community elected Dario Gallegos, a Nuevomexicano merchant, as chairman, and Fred Walsen, a Prussian storeowner, agreed to serve as secretary.47 The committee’s plan was straightforward: unite as a community, and not as separate racial groups, to resist the Chaves Bill. Their argument, too, was very simple: they had been “citizens” of Colorado for quite some time and wished to remain as such.48 Given the racial arguments forwarded in support of the Chaves Bill, the emergence of a multiracial coalition in Costilla County may appear surprising. But community relationships among the San Luis Valley’s whites and Nuevomexicanos were hardly unprecedented.

Whites and Nuevomexicanos had relied on one another since the 1860s to maintain the valley’s sheep economy. Sheep arrived in the San Luis Valley in the mid-nineteenth century alongside Nuevomexicano settlers who found the region to be ecologically conducive to sheepherding. Expansive pasture dominated the valley, and Ute hunting parties kept deer and bison populations under control and prevented overgrazing.49 In the early period of the valley’s Nuevomexicano settlement, Nuevomexicanos managed the valley’s sheep population through the partido system. Under a partido contract, a wealthy sheep owner entrusted his sheep to a hired shepherd, who then raised the sheep for the length of the contract, returned an agreed-upon number of animals to the owner, and kept any surplus animals for their own use or sale.50 Partido contracts locked Nuevomexicano shepherds into a labor system where they produced wool in the valley but rarely found themselves responsible for its export. When whites began settling in the valley in the 1860s, they often filled the role of the exporter and shipped Nuevomexicano wool to eastern markets at a considerable profit.51

This drawing by artist Henry W. Elliot of the 1869 Hayden expedition shows Fort Garland beneath the Sierra Blanca.

While the sheep economy was not egalitarian—Nuevomexicanos generally performed a laboring role and whites tended to act as commercial intermediaries—it did foster interaction among the two populations. In the 1870s, valley Nuevomexicanos and whites defended one another from external influence, especially when external land developers tried to buy and develop remnants of the Spanish-Mexican land grants at the expense of local residents. Ferdinand Meyer, who, like Walsen, immigrated from Prussia and established a mercantile outfit in Costilla, led the local resistance against William Blackmore, an English financier who sought to disrupt the rhythms of the local sheep economy in the 1870s.52 Much like the committee opposed to the Chaves Bill, Meyer desired to maintain a multicultural landscape in the San Luis Valley as long as it was financially profitable. And, much like Meyer, Walsen and his fellow organizers found community solidarity to be crucial to their success.

Unlike Meyer’s resistance to British interlopers, which stemmed from economic relationships with Nuevomexicanos, Gallegos, Walsen, and other San Luis Valley residents rejected the Chaves Bill by making shared claims to Colorado citizenship. Referring to the group as the “citizens of Costilla,” Walsen and the committee argued that “to be annexed would be a sacrifice to the people of this valley.”53 Moreover, the possibility of annexation produced an identity crisis among San Luis Valley residents. Claiming to speak on behalf of the valley, the town of San Luis (or, more likely, Walsen and Gallegos’s committee) disseminated an editorial expressing the valley’s anxiety. Valley populations, San Luis claimed, had lived for years “supposing they were citizens of Colorado.”54 According to San Luis, a new boundary line would not only prove disastrous for business in the valley but would isolate communities from the territory they considered their rightful home.

Supportive coverage of the town of San Luis’s editorial campaign aligned with the community’s claim to Colorado identity, and reporters who opposed annexation also referred to valley residents as citizens. The prevalence of articles advocating for the “citizens” of the San Luis Valley indicate that Weiler’s racially charged support for the Chaves Bill was not shared by all Coloradans.55 But Weiler and the citizens of Costilla shared one conviction throughout the debate over the Chaves Bill: inscribing identity categories on Nuevomexicanos—either as racial others or as fellow citizens—was also a method of defining Coloradan identity. In 1870, the Chaves Bill made clear that Nuevomexicanos who resided within the territorial boundary would remain citizens with geographical claims to Coloradan identity and, by extension, to American identity as well. The debate over the bill, however, ensured that Nuevomexicanos’ racialized identity would prevent them from full inclusion in the Colorado and American community.56

The Chaves Bill died sometime in 1870, never having gained significant support in Congress or the San Luis Valley.57 As far as Chaves’s representatives were concerned, San Luis Valley communities sent them back to New Mexico without petition signatures or support in the local press.58 We can only imagine Baden Weiler’s frustration as the San Luis Valley continued to host a sizeable Nuevomexicano population that, like Weiler, maintained a geographical and legal status as citizens of Colorado and the United States.

For the San Luis Valley’s Nuevomexicanos, however, the Chaves Bill’s demise marked only a temporary moment of inclusion as full-fledged members of the Colorado Territory. The racial identity that proponents of the Chaves Bill applied to them only hardened, ensuring that the racial and geographical borders of American identity driving Chaves’s proposal would continue to shape the Nuevomexicano experience and sense of belonging in Colorado and the American West.

In the early twentieth century, the racial boundary that Chaves’s supporters drew at the Colorado–New Mexico border resurfaced in the Arizona and New Mexico campaigns for statehood. Colorado shed its territorial status in 1876, but Arizona and New Mexico’s location on, as the Chaves Bill defined it, the Mexican side of the 37th parallel delayed their statehood bids. Not unlike the debate surrounding the Chaves Bill, race played a central role in the southwestern statehood campaigns. Historian Linda Noel suggests that Arizona gained statehood more easily than New Mexico due to a white demographic majority and a statehood campaign that highlighted white control over territorial politics.59 New Mexicans also made claims to whiteness to achieve statehood and emphasized their Spanish ancestry to highlight a shared European heritage between New Mexicans and other Americans.60

Statehood eventually arrived in the Southwest—reaching Arizona and New Mexico in 1912—but Nuevomexicanos persisted within a set of racialized borders.61 From the Chaves Bill through the statehood campaigns, the 37th parallel transformed Nuevomexicanos from citizens of Colorado and the United States into foreigners within American (read: white) communities.

Today, the Southwest’s overt racial boundary lies at the U.S.-Mexico border, where the international boundary separates nonwhite migrants (often incorrectly homogenized as “Mexican”) from American communities. The debate over the Chaves Bill, however, continues to emerge in the American interior, where Mexican American claims to Coloradan and American identity remain unstable. In 2017, this instability met Bernardo Medina of Gunnison County, Colorado, with temporary incarceration. Medina, born in Montrose, Colorado, found himself detained in U.S. Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) custody for three days following an appearance in Gunnison County Court. ICE officers, according to Medina, held him on suspicion that he was not, as he claimed, an American citizen, telling Medina, “you don’t look like you were born in Montrose.”62 Three days later, officials released Medina after an immigration rights advocate delivered his birth certificate to an ICE facility in Aurora, Colorado.

As Medina exited the facility, he walked through the Colorado landscape like the Nuevomexicanos of 1870. Medina, despite his legal citizenship, had been marked as an outsider because some Coloradans, both past and present, have racialized the region’s Hispanic community as nonwhite, noncitizens.

Although Americans who identify with the Latinx community, like the nineteenth-century Nuevomexicanos of the San Luis Valley before them, exercise citizenship rights, racialized state and international borders still mark them as possible foreigners in their own communities.63 As public debate surrounding the Chaves Bill indicates, whites marked the Latinx community as a cohort of racial foreigners long before the rise of immigration controls targeting Mexican migrants in the twentieth century. State borders, and not only international ones, played a central role in the early racialization of Mexicans in the Southwest.

While the Chaves Bill calls attention to a moment of border conflict and race-making in territorial Colorado, its legacy also demands that we consider how the American interior continues to operate as a key site for the racialization of American identity. As the San Luis Valley’s frustration with Coloradans like Baden Weiler and Medina’s encounter with immigration officials both suggest, race often supersedes legal and geographical claims to Coloradan and American identity. For Medina, certainly, the contemporary reverberations of the Chaves Bill were not without consequence.

For Further Reading

For broader context on the Nuevomexicano experience in the San Luis Valley and the Colorado Territory following the U.S.-Mexican War, see Virginia Sánchez’s Pleas and Petitions: Hispano Culture and Legislative Conflict in Territorial Colorado (2019), Derek Everett’s Creating the American West: Boundaries and Borderlands (2014), and Virginia McConnell Simmons’s The San Luis Valley: Land of the Six-Armed Cross (second edition, 1999). On the relationship between race and citizenship identity in American history, readers should consult Kunal Parker’s Making Foreigners: Immigration and Citizenship Law in America, 1600–2000 (2015) and Natalia Molina’s How Race Is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts (2014).

The Colorado newspapers referenced in the author’s endnotes can be accessed via the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection (coloradohistoricnewspapers.org); access those outside of Colorado via the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America database (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov). Access congressional records via the Library of Congress at memory.loc.gov.

NOTES

Maps throughout physical and digital copies of this article were created using ArcGIS® software by Esri. ArcGIS® and ArcMap™ are the intellectual property of Esri and are used herein under license. Copyright © Esri. All rights reserved.

1. On the particulars of the Chaves Bill as covered in the press, see Rocky Mountain News, February 7, 1870; the “Chaves Bill,” as local Coloradans and New Mexicans referred to it, is plausibly one of two bills, both of which Chaves introduced on January 24, 1870. The first (H.R. 954) is a bill authorizing the New Mexico Territory to create a constitution and state government in preparation for admission for statehood and includes language proposing to redraw the state boundary. It is possible, based on the geographic bounds laid out in the bill, that Saguache County would have been annexed as well. Costilla County and Conejos County, however, became the focus of public debate over the bill and, therefore, are the focus of this essay. The second (H.R. 956) only proposes a new northern boundary for the territory but makes no reference to statehood. See US Congress, House, January 24, 1870, “A Bill to Authorize the People of the Territory of New Mexico to Form a Constitution and State Government, Preparatory to Their Admission to the Union on an Equal Footing with the Original States,” H. Res. 954, 41st Cong., 2nd Sess., Library of Congress; see also US Congress, House, January 24, 1870, “A Bill to Define the Northern Boundaries of the Territory of New Mexico,” H. Res. 956, 41st Cong., 2nd Sess., Library of Congress.

2. While Conejos County stretches across southwestern Colorado, census records indicate that most of its population lived in Conejos (located in the San Luis Valley), with some recorded individuals on the Ute Indian Reservation west of the San Juan Mountains. My calculation of the Nuevomexicano population in both counties at the time of the Chaves Bill is based on a close reading of the 1870 manuscript Census records. Because the Census Bureau did not differentiate between whites and Mexicans, I have assigned a “race” to each individual living in Costilla County and Conejos County based on name, place of birth, and parent’s place of birth in accordance with how racial categories were deployed in the 1870s American Southwest. All data generated through HeritageQuest. For records on individuals living in Conejos County and Costilla County, see Department of the Interior, Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States, 1870, Population Schedules, NARA Microfilm Publication M593, 1,761 rolls, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed via HeritageQuest.

3. On Euroamerican settlement in the late 1850s and 1860s, see Virginia McConnell Simmons, The San Luis Valley: Land of the Six-Armed Cross, 2nd ed. (Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1999), 111–39.

4. Phillip B. Gonzales and Virginia Sánchez, “Displaced in Place: Nuevomexicanos on the North Side of the New Mexico–Colorado Border, 1850–1875,” New Mexico Historical Review 93, no. 3 (Summer 2018), 275.

5. Historian Derek Everett has similarly explored how race operated at the nineteenth-century New Mexico border, examining both an earlier attempt by Francisco Perea to redraw the boundary in 1865 and the importance of race to Colorado’s statehood identity. See Everett, Creating the American West: Boundaries and Borderlands (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), 167–89.

6. San Luis, “More About Annexation,” Colorado Chieftain (Pueblo), February 17, 1870.

7. On the shift from strict military and mining interests to permanent settlement and mineral extraction, see McConnell Simmons, The San Luis Valley, 125–39; see also Michael Geary, Sea of Sand: A History of Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 79–101.

8. Kunal Parker, Making Foreigners: Immigration and Citizenship Law in America, 1600–2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

9. The study of the relationship of race, American identity, and borders has received promising attention by borderlands historians. This essay suggests that the Chaves Bill reflects, similar to other moments in American western history, a moment when we see race being constructed in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. On race-making in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, see Katherine Benton-Cohen, Borderline Americans: Racial Division and Labor War in the Arizona Borderlands (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009); Linda Gordon, The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999); Rachel St. John, Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011); for a study that explores blackness in the Southwest, see James Leiker, Racial Borders: Black Soldiers Along the Rio Grande (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2002); this essay also makes use of Jared Orsi’s approach to borderlands history, in which Orsi identifies borderlands as spaces where border categories—borders of geography, race, and citizenship in the case of the Chaves Bill—are undergoing a process of “construction and contestation.” See Orsi, “Construction and Contestation: Toward a Unifying Methodology for Borderlands History,” History Compass 12 (May 2014): 433–43.

10. A detailed sketch of Chaves’s early life can be found in his obituary that followed his death by assassination (according to the press) in 1904; see “Escorted to His Final Resting Place,” Santa Fe New Mexican (Santa Fe), November 30, 1904; for a more detailed biographical sketch, see Maurilio E. Vigil, Los Patrones: Profiles of Hispanic Political Leaders in New Mexico History (Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1980), 56–62; see also William Keleher, Turmoil in New Mexico, 1846–1868 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1952), 480–1, fn1.

11. For records of Chaves’s attendance at St. Louis University, see Catalog of St. Louis University, vol. 1, 1828–1850, Saint Louis University Library Digitization Center, St. Louis, Missouri.

12. Boarding students were listed with their family’s place of residence, and the young José’s records list his family as living in Santa Fe by 1841; see Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the Saint Louis University, Missouri, 1841–1842, Saint Louis University Library and Digitization Center; on Chaves’s family background, see Vigil, Los Patrones, 56–62.

13. “Escorted to His Final Resting Place,” Santa Fe New Mexican, November 30, 1904.

14. On Chaves’s congressional career and the relationship of territorial interests to politics in Washington, see Howard Lamar, The Far Southwest, 1846–1912: A Territorial History, revised ed. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000) 116–7; see also Robert Larson, New Mexico’s Quest for Statehood, 1846–1912 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1968), 91–103.

15. On Heath’s involvement and accusations against Clever, see “Another Trick Exposed,” Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, March 14, 1868.

16. On later accusations of fraud against Chaves, see “The Manifesto,” Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, March 13, 1869; on Heath’s success in securing the delegacy for Chaves, see “Another Trick Exposed,” Santa Fe Weekly Gazette.

17. For an overview of San Luis Valley geography and topography, see Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, Water Supply Paper 240: Geology and Water Resources of the San Luis Valley, Colorado, by C. E. Siebenthal (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910).

18. On the remote nature of the San Luis Valley and the surrounding area, especially the mines in the San Juan Mountains, see Cathy Kindquist, “Communication in the Colorado High Country,” The Mountainous West: Explorations in Historical Geography, edited by William Wyckoff and Lary M. Dilsaver (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 114–37.

19. On the circumstances surrounding the establishment of the Colorado–New Mexico boundary at the 37th parallel, see Everett, Creating the American West, 170–2.

20. On Tata Atanasio and the early settlement of the San Luis Valley, see Thomas Andrews, “Tata Atanasio Trujillo’s Unlikely Tale of Utes, Nuevomexicanos, and the Settling of Colorado’s San Luis Valley,” New Mexico Historical Review 75, no. 1 (2000): 4–41; on Carlos Beaubien and the Sangre de Cristo Grant, see Simmons, The San Luis Valley, 77–87; see also Herbert O. Breyer, William Blackmore: The Spanish-Mexican Land Grants of New Mexico and Colorado, 1863–1878 (Denver: Bradford-Robinson, 1949); for an excellent overview of the Spanish-Mexican land grant system and a detailed discussion of how race operated on the nearby Maxwell Grant, see Maria Montoya, Translating Property: The Maxwell Grant and the Conflict over Land in the American West, 1840–1900 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002).

21. Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States, Population Schedules.

22. Ibid.

23. Valdez and Salazar’s lobbying efforts were reported to the press by local residents of Guadalupe in Conejos County, who promptly rejected Valdez and Salazar’s overtures; see Juan B. Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Rocky Mountain News, February 4, 1870.

24. Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Daily Rocky Mountain News.

25. Ibid.

26. On the lynching of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the Southwest, see William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

27. On the circumstances of the Ute discovery of Jose Roderigo’s body and the implication that he was lynched (which the press’s reference to his alleged criminal behavior—it is unclear if Roderigo was found guilty or just held temporarily—appears to justify), see “Wednesday’s Local Matters,” Rocky Mountain News, May 11, 1870.

28. Ibid.

29. Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Rocky Mountain News. For a discussion of frontier or rough justice in the Southwest, see Durwood Ball, “Cool to the End: Public Hangings and Western Manhood,” in Across the Great Divide: Cultures of Manhood in the American West, edited by Matthew Basso, Laura McCall, and Dee Garceau (New York: Routledge, 2001), 97–108.

30. Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Rocky Mountain News.

31. Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States, Population Schedules.

32. Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Rocky Mountain News.

33. In the 1860s and ’70s, Mexicans increasingly occupied what James Barret and David Roediger term an “inbetween” status of non-Anglo whites in the late nineteenth century. Unlike European immigrants, who, according to Barrett and Roediger, underwent a process of “whitening” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Hispanos in the Southwest were increasingly stripped of their whiteness as Anglos recategorized them as a distinct, Mexican race. In effect, racial arguments in support of the Chaves Bill stripped Nuevomexicanos’ citizenship claims and, with them, Nuevomexicanos’ whiteness. On inbetween peoples and critical whiteness studies, which underpin my interpretation of how Chaves and others constructed the northern territorial boundary as a racial border in 1870, see Barrett and Roediger, “Inbetween Peoples: Race, Nationality, and the ‘New Immigrant’ Working Class,” Journal of American Ethnic History 16, no. 3 (Spring 1997): 3–44; see also Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998). Kunal M. Parker applies a similar approach in his study of citizenship law, and Nuevomexicanos north of the 37th parallel underwent a process of being “rendered foreign” in the late nineteenth century; see Parker, Making Foreigners.

34. US Congress, January 29, 1795, “An Act to Establish a Uniform Rule of Naturalization; and to Repeal an Act Heretofore on the Subject,” Chap. XX, 3rd Cong., 2nd Sess., Library of Congress.

35. Mexicans’ legal whiteness and their ability to attain American citizenship are codified in Article VIII of the treaty; see United States, February 2, 1848, Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Library of Congress.

36. Baden Weiler, “The Southern Counties—The Other Side,” Rocky Mountain News, March 16, 1870.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid. Gonzales and Sánchez, “Displaced in Place,” 292.

40. Weiler, “The Southern Counties,” Rocky Mountain News.

41. Department of the Interior, Geological Survey, “Preliminary Field Report of the United States Geological Survey of Colorado and New Mexico,” by F. V. Hayden (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1869), 121–2; on Hayden’s scientific activity as a U.S. Geologist, see Mike Foster, Strange Genius: The Life of Ferdinand Hayden (Niwot, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1995); see also James Cassidy, Ferdinand V. Hayden: Entrepreneur of Science (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

42. “The Mexican Bullwhacker: A Character Sketch,” Las Animas Leader (Las Animas, Colorado), November 1, 1873.

43. This linkage emerged in an untitled article in The Colorado Transcript, where the author explores the pending English language bill and indicates that, if the Chaves Bill were to succeed, the debate over the language bill would be settled by the removal of Mexicans from the Colorado Territory. See “Untitled,” Colorado Transcript (Golden City), February 16, 1870.

44. On attempts to make Colorado documents appear only in English, see Gonzales and Sánchez, “Displaced in Place,” 290–1.

45. Weiler, “The Southern Counties,” Rocky Mountain News. On Weiler’s editorial in the context of the campaign to issue the Colorado Territory’s laws in English only, see also Gonzales and Sánchez, “Displaced in Place,” 291–2.

46. Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Rocky Mountain News.

47. Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States, Population Schedules.

48. Fred Walsen, “Anti-Annexation Meeting,” Rocky Mountain News, February 25, 1870.

49. On the relationship of Ute hunting to the region’s ecology, see Andrews, “Tata Atanasio Trujillo’s Unlikely Tale,” 11–13; for a more general overview of Utes in the San Luis Valley and surrounding region, see James Brooks, Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); see also Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006).

50. On the partido system in the San Luis Valley, see Breyer, William Blackmore, 11–16; on the characteristics of the partido system, see Montoya, Translating Property, 142–3.

51. On the interaction of white merchants and Nuevomexicano producers—generally shepherds—see Breyer, William Blackmore, 107–9.

52. On Meyer’s arrival in the San Luis Valley, see Simmons, The San Luis Valley, 85; on Meyer’s resistance to Blackmore’s efforts on the Sangre de Cristo Grant, see Breyer, William Blackmore, 107–16.

53. Walsen, “Anti-Annexation Meeting,” Rocky Mountain News.

54. San Luis, “More About Annexation,” Colorado Chieftain.

55. The use of “citizen” was common among press reports that opposed the Chaves Bill. In addition to articles cited above, see, for example, “Daily News,” Rocky Mountain News, March 1, 1870. The Rocky Mountain News also referred to the residents of the San Luis Valley as citizens in a response published alongside Weiler’s editorial; see “Editorial Note,” Rocky Mountain News, March 16, 1870.

56. On the relationship between racial and national identity, both of which infused Mexican identity in nineteenth-century America, see Andrés Reséndez, Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800–1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005); see also Anthony Mora, Border Dilemmas: Racial and National Uncertainties in New Mexico, 1848–1912 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); see also Linda C. Noel, Debating American Identity: Southwestern Statehood and Mexican Immigration (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014); for recent approaches to Mexican identity in twentieth-century American history, see Natalia Molina, How Race Is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); see also Julie Weise, Corazón de Dixie: Mexicanos in the U.S. South since 1910 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

57. It is unclear exactly when the Chaves Bill died but the congressional record does not show any movement out of committee. By mid-1870, press coverage of the bill disappears from the archival record, indicating that the bill was no longer a point of concern for southern Coloradans by midsummer.

58. The citizens of Guadalupe, Colorado, according to Jaquez, gave Valdez and Salazar “the mortification of being left out in the cold, with the free option of returning to their paradise in New Mexico just as soon as they see fit.” See Jaquez, “From Guadalupe,” Rocky Mountain News.

59. Linda C. Noel, “‘I am an American’: Anglos, Mexicans, Nativos, and the National Debate over New Mexico and Arizona Statehood,” Pacific Historical Review 80, no. 3 (August 2011): 451–7

60. Noel, “I am an American,” 442–7.

61. Noel, “I am an American,” 465–7.

62. Blair Miller, “ICE Agents Illegally Detained Colorado US Citizen for Days because He was Hispanic, Lawsuit Claims,” Denver7 News, March 8, 2017.

63. On producing foreigners through racialization in the American interior and the importance of state borders, see Parker, Making Foreigners, 4–10.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Immigration to Colorado: Myth and Reality For most of its history, America has been a haven for those seeking a better life and a refuge for those fleeing for their lives. Indeed, since its inception, America has been an inspiration to others, a place where the downtrodden could find hope. Among the proponents of immigration was President John F. Kennedy, who laid out his inclusionary vision of America in his 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants.

Vision and Visibility Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice.

Kitchen Table History, Even When We’re at Different Tables While our holidays this year may be physically distant, we can still find ways—via phone or Zoom—to connect through reminiscing and stories. This actually feels even more important this year if you know elders who are isolating and alone.