Story

What Has Knowing a Little Colorado History Done for Me Lately?

The late Barbara E. Sternberg was a member of the Denver Woman’s Press Club who in 2011 wrote the biography Anne Evans—A Pioneer in Colorado’s Cultural History. This article is reprinted with permission from the blog Sternberg developed after this book was published. Anne Evans was a resident of the present-day Center for Colorado Women’s History at the Byers-Evans House Museum, one of History Colorado's museums.

One of the plusses in working on a biography of Anne Evans was the education it gave me about the history of Denver and Colorado. A subject about which I was woefully ignorant. And so, I discovered, were many of my well-educated Denver friends. Two recent [2012] news items—that Denver’s Civic Center had been declared a National Historic [Landmark], and that the restoration of the old Carnegie Library on the Civic Center had been completed—triggered a host of memories of what I had learned about the early history of both of these projects. And of the considerable role Anne Evans played in their development.

Leaving the Carnegie Library for a later blog, I’d like today to share something about the long fight to establish a Civic Center in Denver. It began shortly after the City and County of Denver was voted into existence in 1904 and Robert Speer elected its first mayor [after having adopted a new charter with a mayor-council government]. The Denver of the time was flourishing but unlovely, making little use of its magnificent setting at the base of the Rockies, and befouling its natural heritage at the juncture of the Platte and its Cherry Creek tributary.

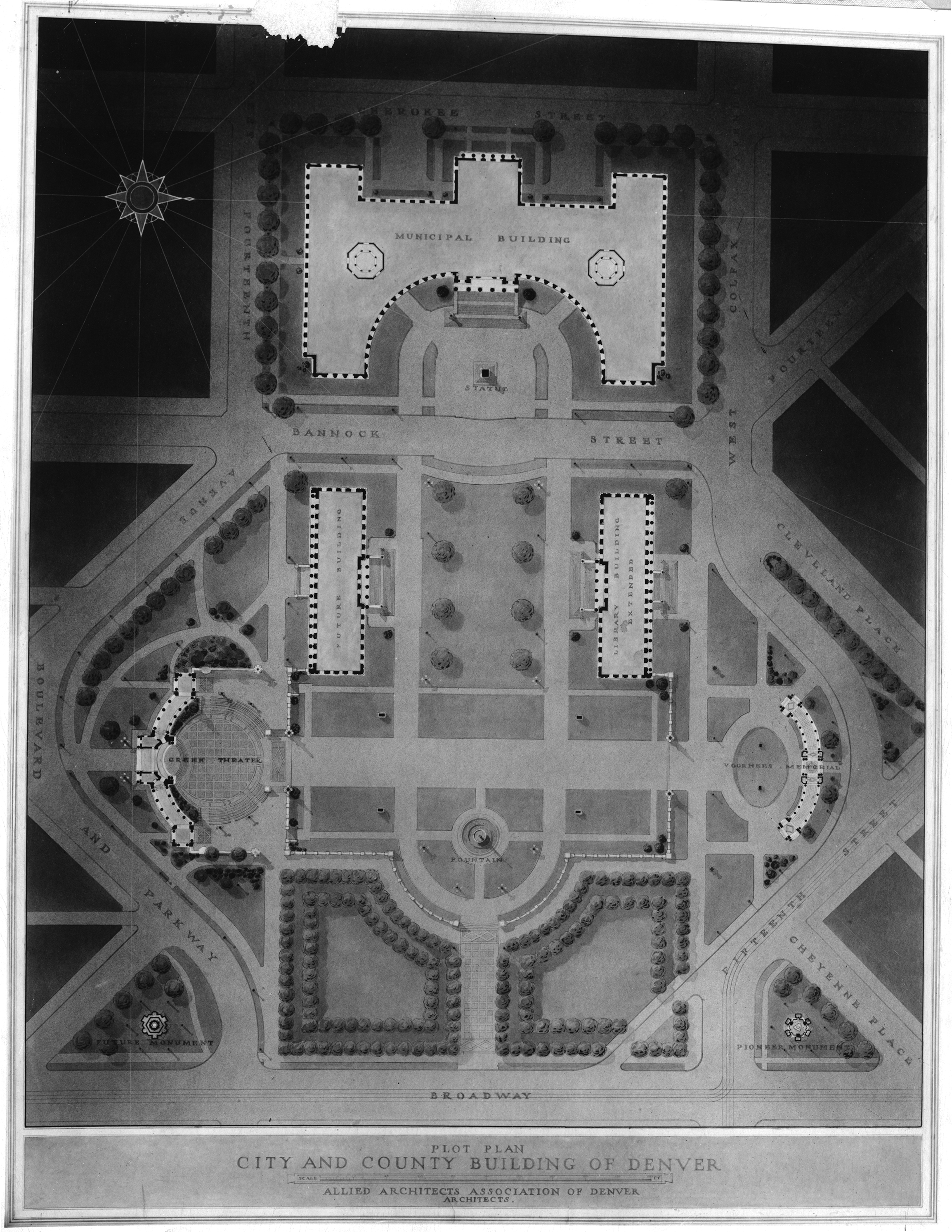

Robert Speer made no secret of his desire to transform Denver into the most successful example of a City Beautiful. It was probably at his prompting that the powerful new Denver Art Commission, of which Anne Evans was one of the original appointed members, recommended in 1904 that a plan be drawn up for the future shape of Denver, and that the plan should include a Civic Center. The first Civic Center plan, submitted by Chicago planner Charles Mulford Robinson in 1906, was for an awkward rectangle linking the State Capitol with the then Denver Municipal headquarters in the old Arapahoe County Courthouse on Court Place. The [proposed Civic] Center had both Broadway and Colfax running through it, and involved the purchase of expensive commercial land. The plan was a failure. It was succeeded by the present configuration, with the State Capitol at one end and requiring a new Denver municipal building at the west end to complete it. The area in between was covered mostly by small houses, much cheaper to acquire than commercial property—and as an added bonus, considerable revenue would result from the sale of the courthouse site.

Slowly the acquisition of the site proceeded. Little other progress was made during the period when Speer left the office of mayor to run for the Senate and Denver experimented with a commission form of government. But when he returned in 1916, along with a public endorsement of a switch to one of the strongest mayoral city governments in the United States, things really began to happen. A final plan developed by Chicago landscape architect E. H. Bennett was adopted, and the shaping of the land with stone balustrades, with a main axis and strong transverse axis bisecting it at right angles, took shape.

Inspired by Speer’s powerful “Give While You Live” campaign aimed especially at Denver’s wealthy citizens, and rigorously monitored by the Art Commission, a program of privately financed donations of structures, like the Voorhies Memorial Gateway, and sculptures, like Bronc[h]o Buster and On the War Trail, enriched the new center.

The last major addition to the Civic Center before the Second World War was the Denver City and County Building. This was where Anne Evans made her major contributions—in three different areas:

-

She was credited with organizing “several hundred civic-minded citizens to assure selection of the present site for the new municipal building and the block-by-block canvas of the city for the sales of bonds to help in acquiring that site.”

-

As an Art Commission member, she was deeply involved in the planning of the new building, and in approving the design of its different artistic elements.

-

As both a member of the commission and of the Board of Trustees of the Denver Art Museum, she quietly helped to organize a consensus that resulted in important gains in the museum’s standing. It was recognized as the city’s official Art Agency, entitled to some municipal support. The entire south end of the new building’s top story was allocated for the museum’s art galleries, achieving its longtime goal of a presence on the Civic Center.

If you’d like to round out this brief history of the Civic Center, you could of course read my recently published biography, Anne Evans—A Pioneer in Colorado’s Cultural History: THE THINGS THAT LAST WHEN GOLD IS GONE [Buffalo Park Press, co-publisher Center for Colorado & the West at Auraria Library, 2011].

[In a future post], a few lines about what Anne Evans called a “sculptured atrocity” that you will not see on the Civic Center—and about the public row between Anne and Mayor Ben Stapleton over the issue. I have found that knowing something about the “backstory” of current developments makes them much more meaningful—and sometimes more entertaining.