Story

How US suffragists adopted UK suffragettes’ militant tactics

Looking ahead to the centennial of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 2020, the women’s suffrage movement and women-led activism was the subject of the National Youth Summit in May.

Hosted by History Colorado, the Smithsonian, and students at five other museums across the country, the live webcast brought students, scholars, teachers, policy experts, and activists together in a national conversation.

Panelists at Youth Summit at History Colorado Center on May 21, 2019. From left: Dani Newsum (Moderator), Candi CdeVaca, Claire Garcia, Polly Baca, and Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold.

Colorado, in fact, became the first state to give women the right to vote on November 7, 1893, by state referendum, requiring popular vote for approval. It was after a campaign led by the Colorado Non-Partisan Equal Suffrage Association, a coalition of women’s organizations, that male voters approved the referendum on equal suffrage.

This victory represented the first time in US history that a state referendum had passed women’s suffrage into law. The Wyoming legislature had granted women the right to vote in 1869, but Wyoming was then still a territory.

The battle for women’s enfranchisement in the rest of the United States continued for many years—with demonstrations, petitions, speeches, and coordinating with fellow activists in England. However, it wasn’t until the next century, on August 18, 1920, that Congress ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which guaranteed voting rights for all women in America.

The upcoming celebrations of this landmark liberation presents an opportunity to highlight how American agitators embraced high-profile methods imported from their British counterparts.

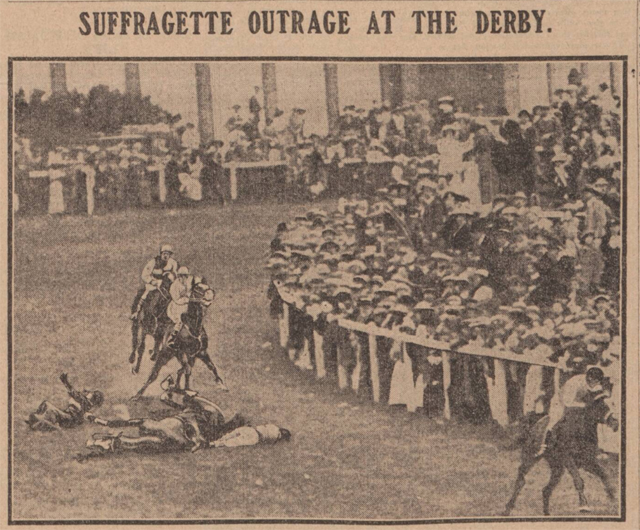

In June 1913, King George V of England witnessed what was to become, arguably, one of the most shocking and defining moments of the global suffragette movement: the trampling to death of campaigner Emily Davison by his horse at the Epsom Derby.

This tragic martyrdom marked ten years of ongoing civil disobedience instigated by British political activist Emmeline Pankhurst, depicted by Meryl Streep in the film Suffragette. Pankhurst founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903 under the slogan “Deeds, Not Words,” and took a more aggressive stance than the preexisting women’s lobbying group.

The main focus became direct and often illegal action to pressure the government to give women equal voting rights as men; they cut telephone wires, set unoccupied churches on fire, broke windows, threw rocks, were dragged through the streets by the police, engaged in hunger strikes, and endured brutal force feedings at the hands of authorities.

Emmeline Pankhurst arrested outside Buckingham Palace June 3, 1914.

Pankhurst, not wanting to restrict her campaign to Britain, traveled to North America in 1916, not only to spread her ideas and tactics on the suffrage movement across the Atlantic but also to raise money from Americans eager to give to the cause of women’s representation.

American suffragists, notably Elizabeth Robins, an actress, and social studies student Alice Paul from New Jersey, were both members of the WSPU while living in England. Both women, inspired by Pankhurst, became staunch propagandists for the movement and Paul was often arrested and imprisoned for partaking in suffrage demonstrations.

They related the militant methods used by the British, which promoted a more progressive and radical movement by the Americans. These activities, in turn, caught the attention of the American government and the public.

The suffragists Ella C. Thompson, left, Alex Shields, Alice Paul and Wilma Keams protesting in 1919.

A transatlantic suffrage movement developed as suffragettes encouraged each other with telegrams and flowers, and introduced leaders to each other.

Alice Paul, returned home in 1910 with her adopted radicalization, split from a more staid women’s organization to form her own National Woman’s Party. Paul’s group focused on forcing the passage of a federal suffrage amendment to the US Constitution—not just by state by state.

Following the same approach as her transatlantic sisters, she staged a political protest of around eight thousand women marching with banners and floats at the White House gates in 1913 the day before President-Elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Many were arrested and jailed for months. Like Pankhurst, Paul utilized prison sentences as a means to claim more political recognition for women.

The consequent media attention of these demonstrations, together with Paul’s own hunger strikes and being force-fed through a tube, helped secure the passage and ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, granting women the right to vote on August 18, 1920.

Marsha Goldstein as Caroline Nichols Churchill, Colorado suffragette, addressing the students at the Youth Summit at History Colorado Center.

The historic victory can be viewed as a direct result of decades of emulating the radical style of their fellow activists across the Atlantic.

In fact, universal suffrage for all women didn’t pass in Britain until 1928—eight years after the United States. Clearly, transatlantic collaboration and the effectiveness of militant tactics factored significantly in women’s suffrage within the Western world.

In anticipation of the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment in 2020, History Colorado is building a collaborative network for sharing resources and promoting programming related to women’s suffrage. We invite any interested organizations and groups to join us for regular meetings to share plans, questions, and ideas. For more information, contact Jillian Allison by email or at 303-620-4933.