Story

The Silver Queen of Cloud City

The spectacular rise—and fall—of Baby Doe Tabor

Colorado’s history is full of colorful characters, and few so colorful as the Silver Queen herself, the legendary Baby Doe Tabor. Famous for her whirlwind romance with silver magnate Horace A.W. Tabor, Baby Doe contributed to Leadville’s dramatic and boisterous early history, earning her place in Colorado lore. From her simple beginnings to her scandalous rise to fame and return to poverty, Baby Doe defied societal norms to shape her own destiny in the American West.

Before she was Baby Doe Tabor, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Bonduel McCourt was born in 1854 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Her birthday is a mystery, but Elizabeth was christened at St. Peter’s Catholic Church on October 7, 1854.

From an early age, Lizzie was spoiled for her beauty. Her mother excused her from household chores and encouraged Lizzie to explore life as an actress. Lizzie became known as the “Belle of Oshkosh” due to her curvy figure, her light golden hair, bright blue eyes, and her peaches-and-cream complexion, which attracted the eyes of many young suitors.

Lizzie met her first husband, Harvey Doe, in April 1876. Lizzie caught Doe’s eye when she secretly entered the Oshkosh ice skating contest and won first prize, much to the consternation of the ladies in the crowd. Doe, enchanted by Lizzie’s beauty and outgoing personality, called on her daily despite his mother’s disapproval. Mother Doe despised Lizzie, whose bold, unconventional social life and status as a common tailor’s daughter made them an unsuitable match.

Despite his mother’s impassioned objections, Harvey and Lizzie became engaged and were married on June 27, 1877. Shortly after, the newlyweds traveled west to make their fortune in gold in Central City, Colorado.

Harvey’s father owned several mining claims, including half of the Fourth of July mine. When the couple arrived in Central City, Harvey struck a deal with his father to oversee the mine and its materialization of ore for two years with the promise of receiving a share of the profits after the first year.

The first six months proved to be difficult for the new couple. Lizzie Doe came to Colorado for fortune and adventure, but quickly learned that Harvey’s spoiled upbringing made him weak in the brutal mining world. To help Harvey operate the mine, Lizzie swapped her dresses for miners' clothes and worked the horse-drawn hoists. Seeing her beauty in the male-dominated mines, miners nicknamed her “Baby” Doe, which forever stuck with her.

The Fourth of July mine eventually played out, forcing Harvey to take a common miner job at the Bobtail Tunnel in Blackhawk. Harvey began to drink heavily as he drifted from job to job and the couple soon quarreled often—over finances, moving, Harvey’s inability to keep a job, and Baby’s headstrong nature.

Baby Doe became pregnant in 1879, but during one ill-tempered fight Harvey accused Baby Doe of cheating, claiming the baby wasn’t his own. He abandoned Baby Doe in Blackhawk alone with no support and she gave birth to a stillborn boy on July 13, 1879.

Harvey returned during the autumn of 1879 wanting to fix their marriage. The couple moved to Denver in 1880, but the marriage soon collapsed when Baby Doe caught Harvey in a brothel. She sued Harvey for divorce on the grounds of non-support and infidelity. Though she faced difficulties due to societal mores of the time, her request for divorce was granted on March 19, 1880.

After the divorce, Baby Doe returned briefly to Central City. With no one left to support her there, Baby Doe took the advice of a friend and moved to Leadville. Located high above the clouds, Leadville’s vibrant and rowdy energy made it a town of opportunity and adventure. Already known to many as the “Beauty of Central,” Baby Doe spent her days exploring the town and her nights being entertained by the lively and rough-neck crowds at Pap Wyman’s saloon.

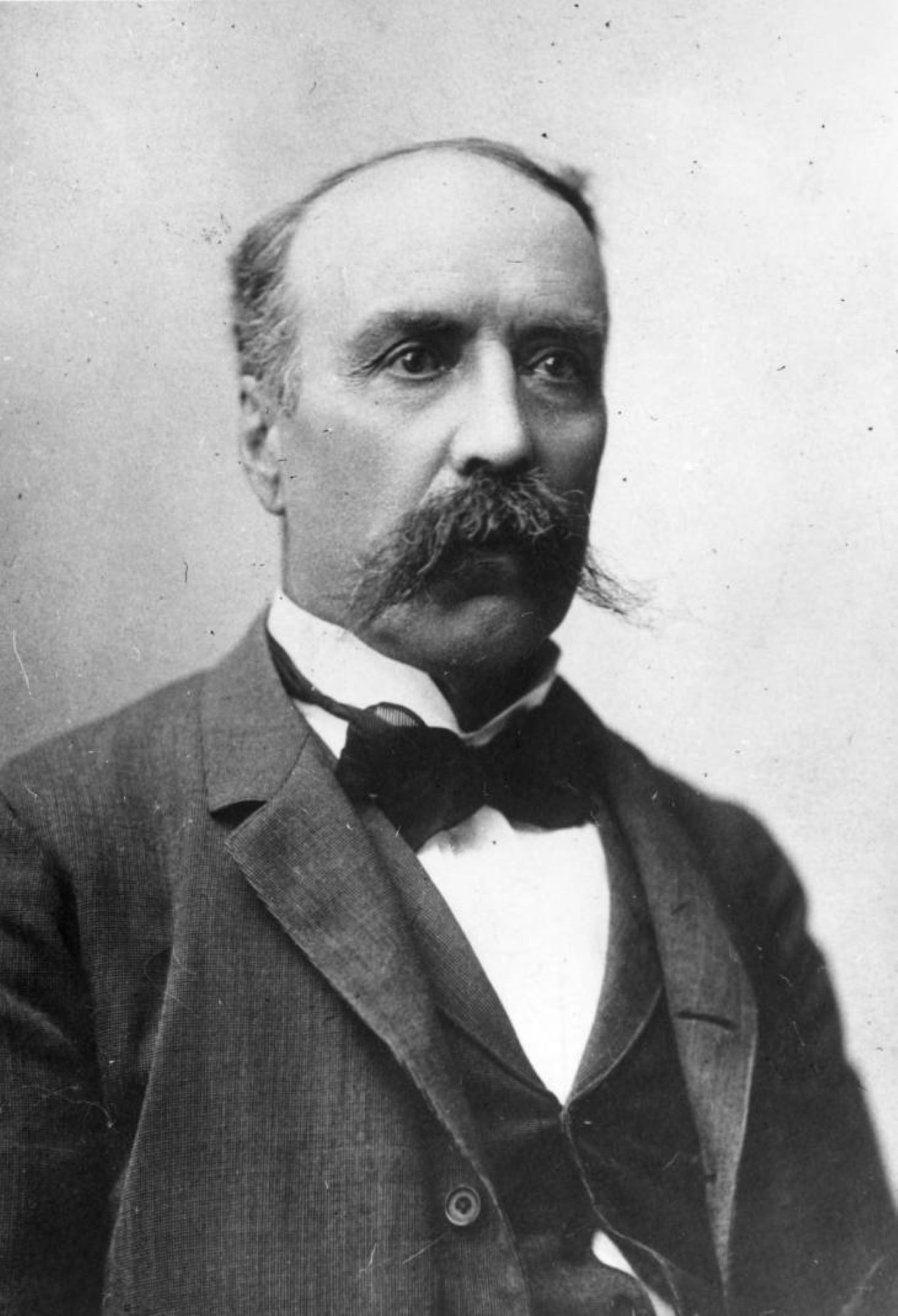

One fateful night Baby was alone in the Saddle Rock Cafe, since she couldn’t afford to attend the opera, when the famous Horace A.W. Tabor walked in. Since arriving in Leadville, she had heard tales of the great Silver King and the millions he made in silver. For Baby Doe, it was love at first sight. Tabor, enchanted by her beauty, invited her to sup with him and the rest is history.

Their love affair began secretly in Leadville since Tabor was still married to Augusta Tabor, who was residing in Denver at the time. Tabor paid off all of Baby Doe’s debt from her time in Central City, moved her into a lavish suite at the Clarendon Hotel, and spoiled her with extravagant gifts of clothes, jewels, and flowers.

Tabor’s love for her grew as his marriage to Augusta deteriorated. Baby Doe was young, out-going, and supportive of his ambitious business and political aspirations. Augusta was shrewd, frugal, and disapproving of Tabor’s carefree and lavish spending. And by September 1881, Tabor and Baby Doe’s scandalous affair was public knowledge.

Augusta knew of the affair and publicly acknowledged their scandal when she refused to attend the opening of Tabor Grand Opera House in Denver on September 5, 1881. A bitter divorce ensued, with Augusta suing for non-support. She claimed Tabor hadn’t supported her since January 1881, but Tabor refused to settle.

Tabor and Baby Doe recognized that Augusta wouldn’t back down, so they devised a plan. Tabor would secretly obtain a court decree in Durango, where he held some property and sway, and they would marry out of state before Augusta could object. On September 30, 1882, Baby Doe and Tabor secretly married in St. Louis, Missouri and Augusta finally acquiesced in January 1883.

Tabor and Baby Doe had a public wedding ceremony in a glamorous Washington, DC ceremony on March 1, 1883. Many prominent national figures, including President Arthur, were in attendance and national newspapers dubbed her “The Silver Queen.” However, many of Washington’s elite refused to attend due to the scandal of their affair and Tabor’s recent divorce.

Tabor and Baby Doe returned to Denver where they continued to live a lavish and reckless life. Matchless Mine alone earned Tabor $80,000 a month, allowing the couple to travel, host grand parties, and wear expensive clothing. Tabor bought them a huge Capitol Hill house and they made regular trips between Leadville and Denver to entertain people of national prominence. But not everything was perfect during this time—although Baby Doe desired to be accepted by the high society women of Denver, she often found herself alienated due to her unconventional lifestyle.

Baby Doe gave birth to their first daughter, Elizabeth Bonduel Lillie in 1884 and their second daughter, Rose Mary Echo Silver Dollar in 1889. Baby Doe and Tabor adored their girls, showering them with gorgeous clothes, expensive toys, and even ponies.

But Baby Doe’s American Dream wasn’t meant to last. In 1893, her world came crashing down when the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act caused the value of silver to plummet. Their property, including Tabor’s prized Matchless Mine, became practically worthless. Baby Doe and Tabor lost everything.

The Tabors went from being one of the richest families in the country to barely affording food for their children. Many of Denver’s elite rejected Baby Doe due to their belief that she was an opportunist who had taken advantage of Tabor’s wealth. However, Baby Doe truly loved Tabor and she remained by his side as they collapsed into poverty. Most of their possessions were sold and Tabor took up work as a common mineworker, and later as Denver’s postmaster, to earn a living. Baby Doe never lost faith in Tabor during these difficult times, expressing that together they would reclaim their fortune.

Tabor never did regain his fortune. He fell ill and died on April 10, 1899. Baby Doe promised him she would hold onto the Matchless Mine, the last piece of Tabor’s legacy, with the hope that one day it would restore the Tabor name.

Baby Doe walks out of the shed addition to her cabin at the Matchless Mine in Leadville, 1934.

Baby Doe dedicated the rest of her life to retaining the Matchless Mine. For thirty-five years she worked hard to secure investors and lessees to repossess and operate the mine. Baby Doe mortgaged the mine several times, each time ending in a failed business venture. She even sold most of her jewelry, except her engagement ring and Tabor’s prized watch fob, to save the mine from foreclosure. Lillie and Silver Dollar initially helped Baby Doe care for the mine, but they soon grew tired and moved away, losing contact with their increasingly obsessed mother.

Baby Doe’s spirited fight and faith in the mine painted her as a madwoman. Baby Doe refused any offer that involved letting the Matchless Mine go. With no income and only the generosity of the Leadville townspeople to support her, Baby Doe resorted to living in the supply cabin at the Matchless. Once a national beauty, the “Madwoman of Matchless Mine” now wandered the streets of Leadville, sustaining herself on a diet of stale bread and suet.

Elizabeth Bonduel “Baby Doe” Tabor died on March 7, 1935 at her beloved Matchless Mine, found frozen on her cabin floor after a snowstorm. Baby Doe may have died in squalor, but the legacy of her time in Leadville carries on. Her wild rags-to-riches story inspired a movie and an opera about her love affair with Tabor. Her tenacious determinism and eccentric life story makes Baby Doe a timeless figure in Colorado history.

For Further Reading

Bancroft, Caroline. Silver Queen: The Fabulous Story of Baby Doe Tabor. Boulder: Johnson Publishing Company, 1965.

Bancroft, Caroline. Tabor’s Matchless Mine and Lusty Leadville. Boulder: Johnson Publishing Company, 1953.

More from The Colorado Magazine

You Should Have Seen It: Colorado Mineral Palace In the Old Historic Northside of Pueblo, Colorado, there’s a park. It’s no longer the biggest park in the city—that ended thanks to interstate construction in the 1950s—but it has a strange mystique, a stately air reminiscent of a bygone era. This may confuse visitors, transplants, and even younger residents, but there are many in the city and beyond who still remember why Mineral Palace Park has its name.

Waiting for Someone to Listen An extraordinary journey of joy and determination, discovered beneath a few layers of tarnish.

Strangers in a Strange Land: The History of Volga Germans in Colorado Volga Germans, also referred to as German-Russians, came from the Russian steppes of the Volga River to Colorado between the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries to labor in the sugar beet fields. The history of their settlement in Colorado is woven into the larger history of immigration in the United States during this period.