Story

Strangers in a Strange Land: The History of Volga Germans in Colorado

Volga Germans, also referred to as German-Russians, came from the Russian steppes of the Volga River to Colorado between the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries to labor in the sugar beet fields. The history of their settlement in Colorado is woven into the larger history of immigration in the United States during this period.

The Volga Germans settled in Russia’s Volga River region as early as the eighteenth century. They emigrated from Germany at the invitation of Catherine the Great, who offered religious liberty and other incentives in return for agricultural labor on the Russian steppes. In the early years of their settlement, the Volga Germans established tight-knit agrarian communities that helped them maintain their ethnic and cultural identity.

Perhaps the most extreme effect on the Volga Germans living in the Russian steppes was the work ethic they adopted in response to their surroundings. They toiled in a treeless wilderness so unlike the greenery that covered the German countryside. The Volga Germans combated the fear and disappointment they felt in response to their surroundings by idealizing work and adopting the saying: “Work rendered life sweet” (Arbeit macht das Leben süss).

The Volga Germans faced gradual “Russification” while they lived in the Volga River region, however. Russian influence began to seep into the Volga Germans’ agricultural methods, dress, and daily vocabulary. The nineteenth century also brought an end to the incentives promised by Catherine the Great, including the exemption from military service that had initially enticed them. With a high concentration of Volga Germans being Mennonites, military conscription went against their pacifist religion.

When the Russification policies enacted in the 1870s threatened the Volga Germans’ way of life, many chose to leave the region. The letters of family and friends who had emigrated from Germany to the United States inspired several thousand Volga Germans to follow in their footsteps.

The highest concentration of these new immigrants settled in the Great Plains and the western states between the 1870s and 1910s. They did so, however, at a time when the United States’ immigration policies became more restrictive. Immigration restrictionists believed that immigration needed to be regulated in order to “guard” the country from the “threat” of foreign-born individuals.

Children of Volga German immigrants found themselves in the fields alongside their parents. They often missed school, or had to take classes in the summer, in order to work the fields.

During the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-centuries, restrictionists directed their efforts primarily at Chinese immigrants, as well as those coming from southern and eastern Europe. They developed a scale that equated “race” with intelligence. This scale, headed by the United States Senate’s Dillingham Commission, placed white immigrants from English-speaking countries at the top, followed by German and other western European immigrants in the middle, eastern and southern Europeans, Asians, and Russians lower than the other groups, and African Americans and other people of color at the bottom.

The Volga Germans fit somewhere between the middle and lower tiers. In contrast to other emigrants from Russia, the Volga Germans resembled Anglo Americans. Their inherent “whiteness” meant that they had a greater chance for social mobility in the United States. Nevertheless, Anglo American settlers looked down on the Volga Germans and their culture.

The Volga Germans’ outward appearance attracted an unpleasant reaction from neighboring settlers. They maintained the dress of their homeland, wearing sheepskin coats and boots decorated with embroidered flowers. In addition, their eating habits–including eating with their hands and having a tendency to spit sunflower seeds as they walked–were regarded as uncivilized by Anglo American standards.

The response to the Volga Germans meant that limited jobs were made available to them. Many took on “stoop labor,” or agricultural labor performed from a squatting position. Those who settled in Colorado often labored in the northeastern sugar beet fields, where they toiled primarily alongside Japanese immigrants and Hispanos. Landowning whites viewed Volga Germans as racially inferior because they took on laborious jobs alongside non-white groups.

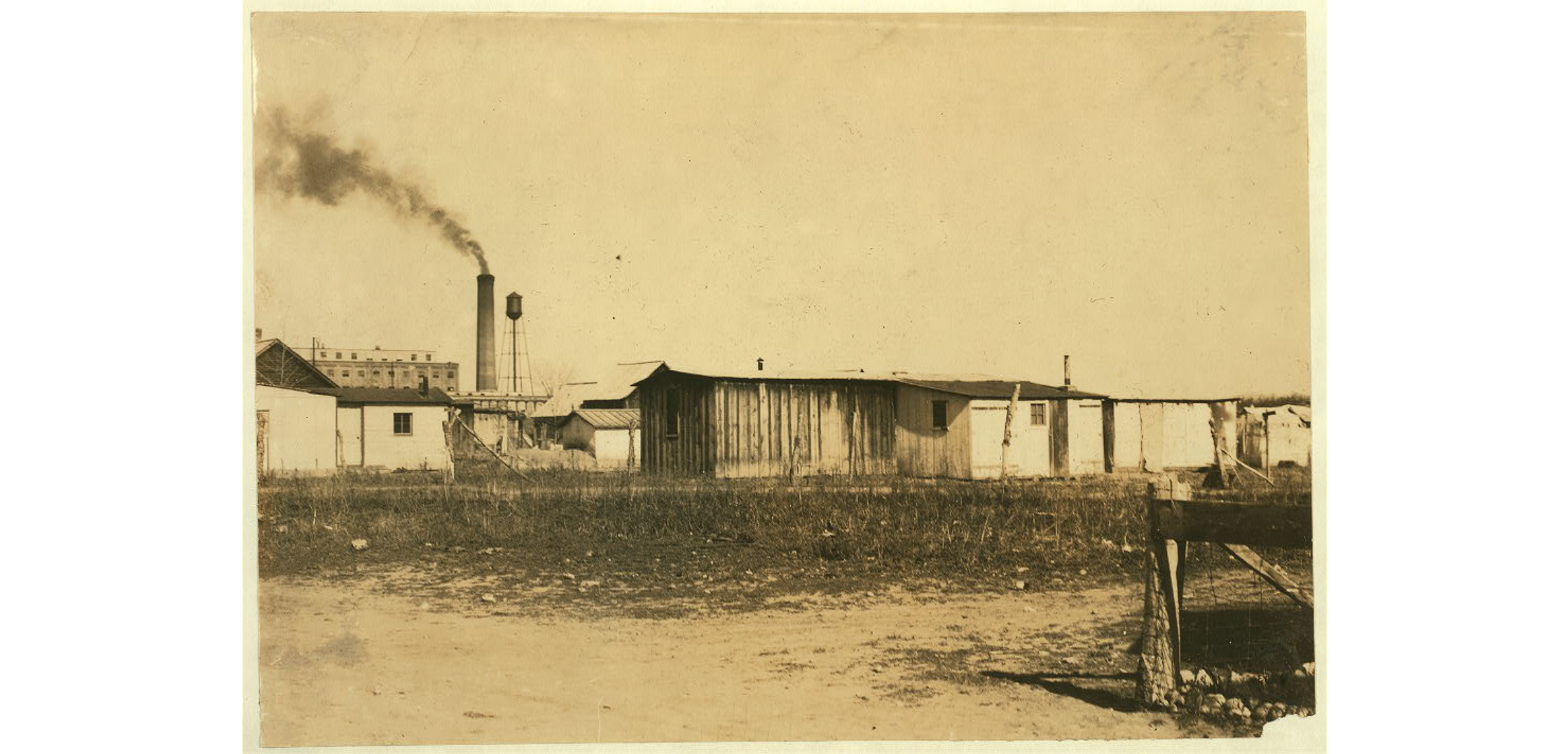

The Great Western Sugar Company established factories in several Colorado towns, including Fort Collins (pictured). The conditions for the workers were poor, which reflected their status as “stoop laborers.”

As the Colorado sugar beet industry expanded in the early 1900s, the Great Western Sugar Company recruited Volga Germans to bring their reputation for unrivaled work ethic into the company’s sugar beet factories. Volga Germans also tended to have large families, which Great Western saw as a way to exploit the most labor in the fields. By having whole families work in the fields, the company believed there would be less chance of laborers abruptly leaving in search of better working conditions.

Sugar beet farming became a family affair, with the children working alongside their parents in the fields for long hours. Oftentimes, farming prevented the children from obtaining a proper education. Sugar beet towns such as Windsor in northern Colorado, later adopted a summer school program for the children that allowed them to learn outside of peak farming times. Nevertheless, the Great Western Sugar Company, and many Volga German patriarchs, placed more emphasis on the children working in the fields than receiving an education. Their lack of formal instruction meant the children had less chance for social mobility outside of the sugar beet industry when they grew up.

It was through the sugar beet industry that the Volga Germans gradually began to acquire lands to establish their own sugar beet farms. Anglo American farmers, however, saw the success of the Volga Germans as a threat to their own farms. Labor competition gave these farmers a reason to maintain their xenophobic attitudes toward the Volga Germans.

The Great Western Sugar Company utilized Volga German labor because of their tendency to have large families. The company realized that families were less likely than individual workers to abruptly leave and seek better working conditions elsewhere.

The beginning of World War I also influenced social perceptions of Volga Germans. Anti-German sentiments spurred attacks on Volga Germans during the first half of the twentieth century. Where they had once been viewed as “not-German-enough,” suddenly the Volga Germans found themselves equated with all Germans, despite their history in Russia. The ambiguities of their ethnic origin–were they German? Russian? Something else?–would also cause some Volga Germans to face backlash during the 1950s. No longer equated with the Kaiser or Nazi Germany, some were labeled communists because of their ties to Russia.

The path to acceptance, the Volga Germans found, came through breaking ties with their own culture. By acquiring lands, establishing homes, and renouncing elements of their culture–including dress and language–Volga Germans received gradual acceptance into society. Mexican and Mexican-American laborers soon replaced the Volga Germans as a source of cheap labor for the sugar beet industry, facing much of the same racism and xenophobia that had been directed at the Volga Germans in earlier decades.

Acceptance into American society came through acculturation and assimilation. While a group of Volga Germans established the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (AHSGR) in Greeley in 1968 (now headquartered in Lincoln, Nebraska), many immigrants and their children were reluctant to acknowledge their heritage. Many children of immigrants in particular expressed ambivalence toward their culture, which often stemmed from the labor they endured as youth and the xenophobia they suffered. Later generations of Volga Germans have likewise lost elements of their heritage, including the German dialect many of their ancestors spoke, as they adopted English as their first language.

Today, the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia continues to preserve and disseminate information about the Volga Germans and their history, in both Colorado and the Great Plains region. Local chapters allow the descendants of the original immigrants to come together and share the culture of their ancestors. In addition, some descendants of Volga German sugar beet farmers still maintain their families’ farms in places like Windsor.

Volga German heritage remains an important piece of Colorado’s agricultural history, in spite of the backlash they faced for bringing their culture to the sugar beet fields.

For Further Reading:

Kloberdanz, Timothy J. “The Volga Germans in Old Russia and in Western North America: Their Changing World View.” Anthropological Quarterly 48, no. 4 (1975): 209–22.

Rock, Kenneth W. “Colorado’s Germans from Russia.” In Germans from Russia in Colorado, edited by Sidney Heitman, 70-80. Ann Arbor: The Western Social Science Association, 1978.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974.

Tichenor, Daniel J. Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

White, Richard. The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Related Articles:

Sugar Beet Industry Bibliography

Immigration to Colorado: Myth and Reality

More from The Colorado Magazine

Creede and World War I—A Knitter’s Tale It was the summer of 2000 and eleven-year-old Lizzie, a beginning knitter, hoped she’d found a mentor—her ninety-four-year-old grandmother, Mary Elting Folsom. Lizzie’s question took Mary back to 1917, several months after the US entered World War I.

Pie It Is! Diet experts and Marxists warn against imbuing things and food with abstract emotions and values. Yet, the alchemy of pie makes it hard to deny that these homespun pastries embody love, family, and human connection.

You Should Have Seen It: Colorado Mineral Palace In the Old Historic Northside of Pueblo, Colorado, there’s a park. It’s no longer the biggest park in the city—that ended thanks to interstate construction in the 1950s—but it has a strange mystique, a stately air reminiscent of a bygone era. This may confuse visitors, transplants, and even younger residents, but there are many in the city and beyond who still remember why Mineral Palace Park has its name.