Story

“Curse of a Nation”

Denver Black Newspapers Respond to the Debut of “Birth of a Nation”

How Denver’s Black newspapers raised the alarm and rallied the resistance against one of Hollywood’s first—and most notoriously racist—blockbusters.

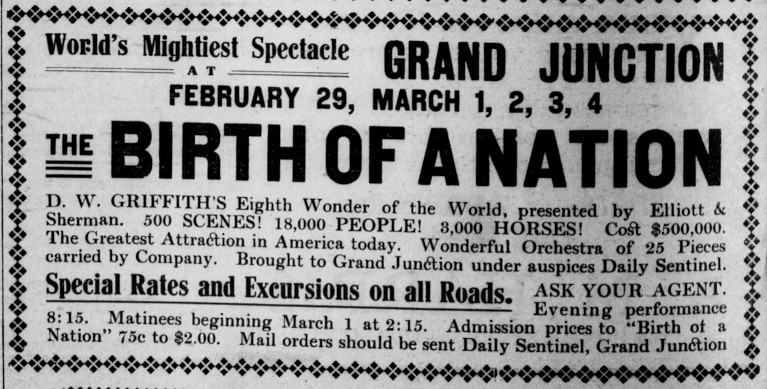

When the film Birth of a Nation premiered in 1915, it was a sensation. Promotions billed it as the “Eighth Wonder of the World” and “the most stupendous Dramatic Narrative Ever Yet Unfolded on any Stage Since the World Began.” Director and producer D. W. Griffith adapted the “photoplay” from Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel and play, The Clansman, which chronicled the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth and the relationship between two families in the Civil War and Reconstruction eras over the course of several years—the pro-Union Stonemasons and the pro-Confederacy Camerons.

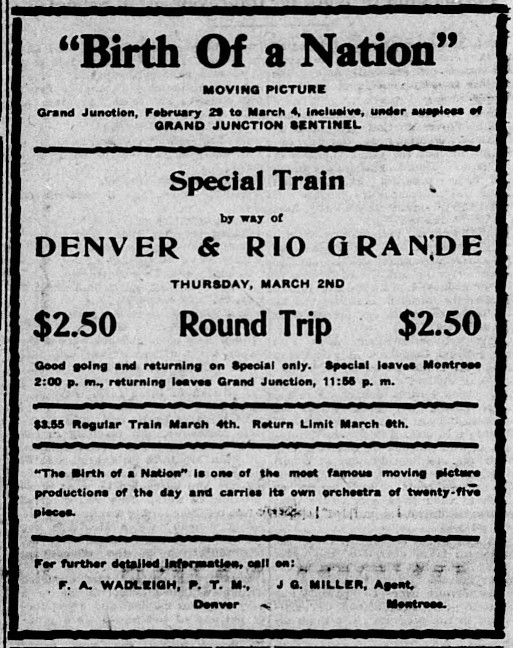

The silent film was a marvel of moviemaking’s early era. It contained 5,000 scenes, featured 3,000 horses, cast 18,000 actors, and required, for full effect, a twenty-five-piece orchestra to provide the soundtrack as it spun from twelve reels of film. The final run time clocked in at three hours and the $500,000 budget was staggering for a film of its time. It was the first American film to be screened at the White House, where President Woodrow Wilson is said to have enjoyed it.

Many of Colorado’s newspaper editors were enthralled and devoted much ink to extolling the film’s merits. The Denver Sunday Times declared it “undoubtedly one of the best ever made—it ranks among the highest in photodramatic art.” The Elk Mountain Pilot of Crested Butte was more effusive in its praise:

The magnificence of “The Birth of a Nation,” the spirit and finish of every detail, the greatness outfits dramatic strength and beauty startles the spectator. Now breathless with the intensity of the production, now in tears, only to break into laughter with the introduction of relieving humor. The spirit and fire of the drama finds echo in rousing cheers of enthusiastic patrons… “The Birth of a Nation” is an inspiration, and at this time every father, mother, son, and daughter should witness the production and then there will be a checking of the war spirit in the hearts of men.

The Lafayette Leader simply described it as “12,000 odd feet of pictorial grandeur.”

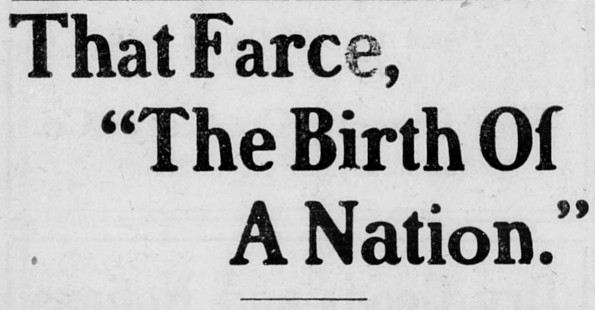

“Three miles of filth” countered William Henry Lewis, the first Black US Assistant Attorney General. Lewis, one of four Black men appointed to high office by then President Taft, sized up the film as “Three miles of filth to blacken and degrade and belittle us in the eyes of our neighbors, among the people and citizens of this community,” in an article urging against the showing of the film in Boston, Massachusetts. He and growing numbers of Americans throughout the country opposed Birth of a Nation because of how Black characters were depicted as ugly and unfair caricatures, and members of the Ku Klux Klan as valiant and gallant knights protecting their way of life. The film, they said, amounted to “magnifying the faults of one race and glorifying the lawlessness of the other.”

Lewis’s article, and many others beside, was reprinted in the Denver Star, a Black-owned, written, and published newspaper that provided a channel by which its readers could "voice their opinions, assert their rights, and demand their due recognition." The editor of the Denver Star, Charles S. Muse, opened his paper’s pages to those who vociferously claimed that Birth of a Nation was a “travesty on history, a breeder of racial antipathy.”

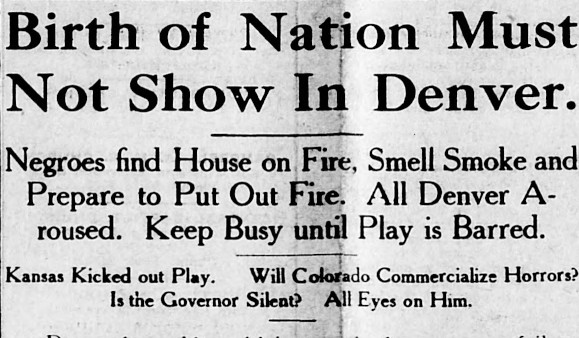

On that count, the film was being banned in places throughout the country. It was run out of Philadelphia in the wake of protests that turned violent. Kansas and Ohio banned the film outright. Detroit fought against it, responding to the call of the local chapter of the Society of Advancement of Colored People to fight against “Dixon’s vile ‘Birth of a Nation’.” The Denver Star, in support, said “what an inspiring sight and lesson it is to our children to see the various Negro and white organizations line up and clear for action.” Denver’s Black community and white allies soon took up the cause. On December 4, 1915, the Denver Star wrote:

It is not so much what is in the play...but it is the damnable influence that it leaves behind to spread and the seeds of lies it sows in honest unsuspecting hearts and minds. It finely makes enemies out of neighbors, creates doubts and suspicions where none heretofore existed, tears down the law and erects lawlessness, it glories in racial differences, disputes and conflicts...Can Denver afford to play with this...violence and destruction?...The “Birth of a Nation” must not show in Denver.

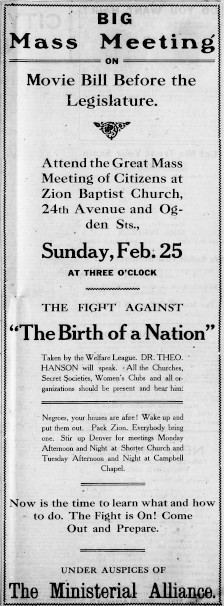

Denver’s Colored Citizens’ League led the charge against the exhibition of Birth of a Nation, sending a petition urging the mayor, Dr. William H. Sharpley, to not allow the showing of the film, declaring that “everything should be done away ahead of time to prevent the exhibition of this play.” The Denver Star called upon its readers to “Arouse your white friends...get them interested in protest...convince them that if they are your friends...to aid you in suppressing that abominable film, a prodigy of lies and race hate.” Mass meetings at some of Denver’s predominantly Black churches called the community and organizations, both Black and white, together against the showing of the film in Denver. The city’s other significant Black-owned newspaper, the Colorado Statesman, urged readers to appeal to the mayor and city commissioners, “who have the power to suppress such photo plays, which will entitle us to protection against denial of civil rights and the disgraces constantly heaped upon us.”

Denver’s Black newspapers galvanized the community to fight against the showing of Birth of a Nation. On December 11, the Denver Star rallied its readers:

Denver is seething with interest in the success or failure of the peaceable law abiding citizens of color either suppressing or partially obliterating the “Birth of Nation,” more properly called “The Curse of the Nation”...Now we must fight harder than ever before. Do not weaken. The Curse of the Nation must not show in Denver...And as a last extremity if everything fails, let us organize a street parade to go up and down 15th, 16th, 17th streets to let everybody know while that hellist play is exhibiting that we are protesting.

With controversy stalking the film and opposition growing, city officials approved a temporary police action to suppress the show in Denver movie houses.The ban was short lived, however, as the court responded with an injunction preventing further interference by the police. Birth of a Nation premiered in Denver at the Palm Theater on West Colfax, on December 14, 1915. The Denver Star printed its response on December 18:

There is no compromise in our opinion of this play; it is outrageous in the extreme; pernicious in executive and movings; suggestive of the poisonous black domination, and has for its purpose and intent the widening of the breach and the stirring up of prejudice between the white and black races of this state and nation.

Birth of a Nation went on to play at the Tabor Opera House, where more than 100,000 people took in the spectacle. The film was shown in movie houses across the state and the social columns of Colorado newspapers teemed with mentions of people traveling to see the photoplay. The Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad offered special excursion fares from Montrose to Grand Junction, where it played under the auspices of the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel and was accompanied by an orchestra of twenty-five musicians.

When the movie ended its run in Denver in January 1916, the Denver Star assessed the damage the showing had done to Denver’s Black community.

No Negro within the confines of Colorado nor white man, for that matter can truly and correctly estimate the insidious and silent harm done to the Negro and the American principles of government, as has been done by the production of the “Birth of a Nation” in Denver and Colorado.

One of the most controversial movies ever made, Birth of a Nation was also one of the most commercially successful, selling out movie houses in limited engagements across the state and around the country. But in Denver, the fight against the film continued. Anticipating its return to Denver after its initial run, Black organizations appealed to the new (and former) Mayor Robert Speer that the most objectionable and inflammatory scenes be cut out of the film entirely. Speer agreed, and the Denver Star reported with satisfaction on August 18, 1917, that “The Mayor with the power to regulate and bar such pictures, took this view and permitted the Denver Star and the N.A.A.C.P. to request certain eliminations, most of which were eliminated.”

The Denver Star, steadfast in its stance against Birth of a Nation, tells a story of resilience and activism, bringing together voices from Black Coloradans to protest a divisive film that preyed upon the worst stereotypes predicated on our country’s painful history of racism and white supremacy. The Denver Star and its counterpart, the Colorado Statesman, capture this important moment of Black history, document Black life in early Denver as it happened, and preserve it for future study and retelling.

You can read all about it for yourself in both the Denver Star and the Colorado Statesman, as well as papers from throughout Colorado dating back to 1859, in the Newspaper Collection at the Stephen H. Hart Research Center at History Colorado, or online on Library of Congress’s Chronicling America and the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection.

More from The Colorado Magazine

"Be True to What You Said on Paper" the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. Here, a medical sociologist and social scientist argue that to truly arrive at equity in America will require a sincere reckoning with founding mythologies of white superiority.

The John R. Henderson Collection: Colorado’s First Licensed Black Architect John R. Henderson transformed the architecture profession in Colorado when he became the state’s first licensed Black architect on October 7, 1959.

Kitchen Table History, Even When We’re at Different Tables While our holidays this year may be physically distant, we can still find ways—via phone or Zoom—to connect through reminiscing and stories. This actually feels even more important this year if you know elders who are isolating and alone.