Story

Don’t Leave Home Without Your Green Book

The Black Travel Experience in Colorado During the Jim Crow Era

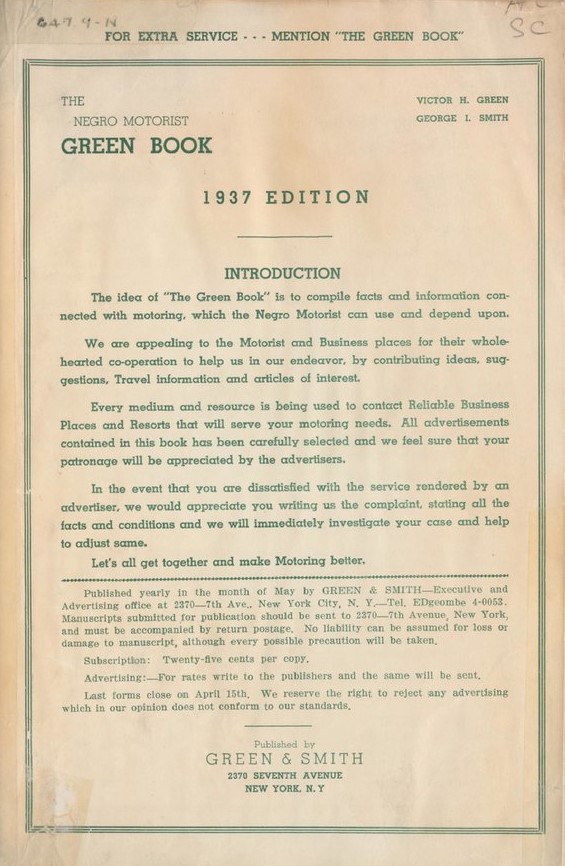

During the rise of auto travel for both business and leisure in the twentieth century, the Green Book helped Black travelers safely navigate their road trips and boost Black businesses along the way.

We Coloradans have road trips in our blood. This is particularly true in this time of Covid-19. In one lazy afternoon, through the windshield or hanging out of the window, a passenger might witness the arid Book Cliffs, skirt the verdant orchards of Palisade, spot a fourteener among the majesty of the Rockies and coast out of the foothills onto the vast space of the open plains. It is a rite and a balm for the venturing spirit. But historically, the carefree travel experience taken for granted by many white travelers was a journey fraught with peril, uncertainty and fear for African American travelers during the rise of the traveling culture of the road—even in Colorado.

The historical record captures monumental travel experiences to places like Estes Park, the gateway to Rocky Mountain National Park, and road-trip stalwarts like Cave of the Winds or Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs. However, that record often obscures and excludes the stories of all American travelers. It is no secret that until the late twentieth century, history generally focused on, and reinforced a narrative focused on, the history of white men. In the late 1960s, this narrative shifted and expanded due to the civil rights movements, to include those of the Black and Hispano communities, and women’s rights. Today, there is a reckoning taking place within the various disciplines of history to expand the historical record to be more reflective of the lived experience of people representing all races, classes and genders. There is much work to be done.

In 2019 the Colorado Historical Foundation, a statewide nonprofit organization with a mission to advance the study and preservation of Colorado history and historic places, embarked upon a study of historical sites associated with the African American travel experience in Colorado during the rise of middle-class automobile travel in the Jim Crow era. Named after a minstrel player, this oft violent period of systemic racism in the United States saw legislation aimed at making certain that people of different races didn’t mingle. This dark and confusing period of US history spanned between the end of the Civil War and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1967, which outlawed overt racism and discrimination.

The Strater Hotel in Durango was advertised in the Green Book as a haven for African American travelers.

The survey work spearheaded by the Foundation is supported with funding through the History Colorado State Historical Fund. This critical work, similar to historical studies being conducted in the national theater, seeks to expand and supplement the historical record for sites such as Lamar’s Alamo Hotel, Pueblo’s Coronado Motel, the Strater Hotel in Durango, and the Chipeta Café in Montrose. What these sites, and many more throughout the state, have in common was that they were advertised in The Negro Motorist’s Green Book. This travel guide was named after founder Victor H. Green, the former New York City postal worker who advised his readers to “always carry your Green Book with you—you may need it” and suggested that with the publication in hand, travelers “may free themselves of a lot of worry and inconvenience as they plan a trip.”

According to historian Candacy Taylor in Overland Railroad, her seminal study of Black travel in America in the twentieth century, “ . . . given the violence that black travelers encountered on the road, the Green Book was an ingenious solution to a horrific problem. It represented the fundamental optimism of a race of people facing tyranny and terrorism. . . . Not only did it show black travelers where they could go, but it was also a compelling marketing tool that supported black-owned businesses and celebrated black self-sufficiency and entrepreneurship.”

This travel guide gained wide recognition in 2018 through the popular Academy Award winning movie, The Green Book, starring actors Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen. The story, although enhanced with a bit of “Hollywood,” follows a Black classical pianist and his hired white driver on a road trip through the precarious Deep South of the 1940s. The movie does a compelling job of portraying the looming violence and basic difficulties encountered on the road by a Black man. The team attempts to navigate this rough terrain through advertisements in the Green Book for restaurants, lodging facilities, and gas stations friendly to African American travelers. Whereas the journey was plagued by normalcy for the Black man, it was an eye-opening experience for the white man.

While the movie focused on the American South, where Jim Crow may have been more notorious, in Colorado the racism displayed toward Black men and women was often no less insidious. When researchers plotted all the Colorado sites listed in the Green Book, plus several other local guides for Black travelers, the map that emerged revealed interesting patterns of mobility as represented by the sites along the major transcontinental highways through the state. For instance, US 50, connecting towns across southern Colorado, saw heavily clustered facilities listed in the guides. The researchers then sorted the buildings by historical use to include a variety of “types” such as hotels, motels, restaurants, service stations, barber and beauty shops, doctors, and so forth. From this information, cursory, or “windshield” surveys were conducted to identify sites that are still standing, with an eye for capturing stories and increasing recognition. The resulting document is the Colorado African American Travel and Recreational Resources Survey Plan.

The Coronado Motel (Lodge) in Pueblo was listed in the Green Book from 1957 to 1966.

Without surprise, the majority of listed sites in the travel guides represented lodging facilities, like the Coronado Motel on Lake Avenue in Pueblo. Built in the Pueblo Revival style, the Coronado enticed travelers with its kitschy Southwest theme and curios. Located in what roadside architectural historian Chester Liebs termed an “approach strip,” it was poised so that merchants got “first crack” at travelers looking for service on their way in and out of town. About the ownership practices of the Copley family who owned the motel for twenty years beginning in 1946, Joyce Copley Reimer recalls, “we didn’t discriminate about anybody. They had the money, there were welcome . . . We didn’t turn anybody away.” Recently, the Coronado Motel was listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its role in social history and, specifically, as a facility that welcomed Black travelers. Only recently has this element of significance been considered as noteworthy within the National Register. The motel paid for the listing in the Green Book from 1956 through 1967, which was the last year it was published.

The Coronado Motel represents the tip of the iceberg. The goal of the Colorado Historical Foundation’s project, ultimately, is to identify sites throughout the state and to document and publicize their role in history. As our nation struggles to reconcile the difficult moments in our history and to create a more inclusive future, projects such as this can be used to identify and protect the places that tell the stories of all Americans.

Author’s Note: Front Range Research Consultants conducted the survey described in this article, identifying sites in The Negro Motorist’s Green Book as well as other travel guides such as the Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers, Smith’s Tourist Guide and even Ebony Magazine’s vacation section from the period. The Colorado Historical Foundation is grateful for their contributions to this project.

More from The Colorado Magazine

The John R. Henderson Collection: Colorado’s First Licensed Black Architect John R. Henderson transformed the architecture profession in Colorado when he became the state’s first licensed Black architect on October 7, 1959.

“Curse of a Nation” Denver Black Newspapers Respond to the Debut of “Birth of a Nation”

"Be True to What You Said on Paper" the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. Here, a medical sociologist and social scientist argue that to truly arrive at equity in America will require a sincere reckoning with founding mythologies of white superiority.