Story

One Flew West

Ken Kesey’s Colorado Childhood

When Ken Kesey described fictional southeastern Colorado settings and characters in one of his novels, he could rely largely on his own memory. The author, who lived in Oregon for nearly all of his life, was born in the town of La Junta, Colorado, in the days of the Dust Bowl.

Ken Kesey and Oregon. It’s one of those enduring literary associations, like Cormac McCarthy and the borderlands, Edward Abbey and desert Utah.

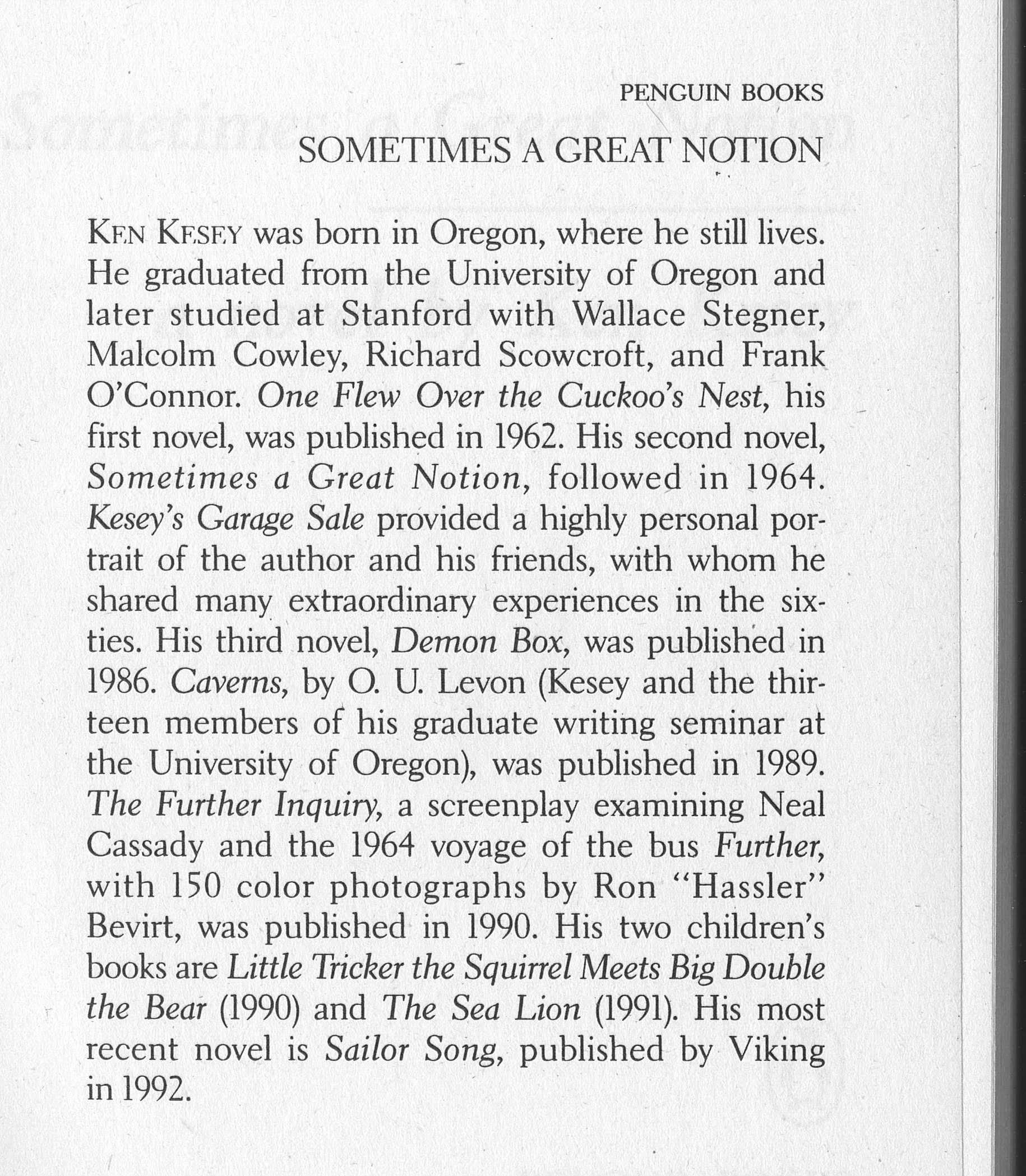

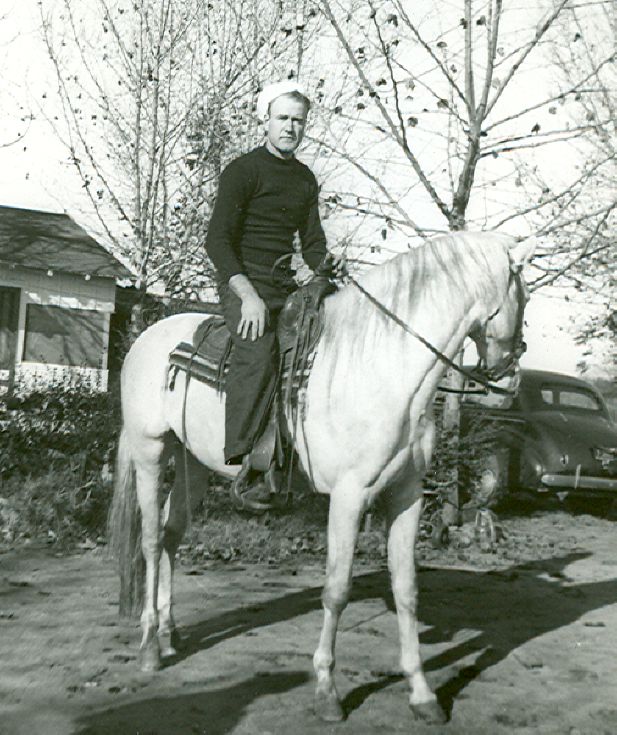

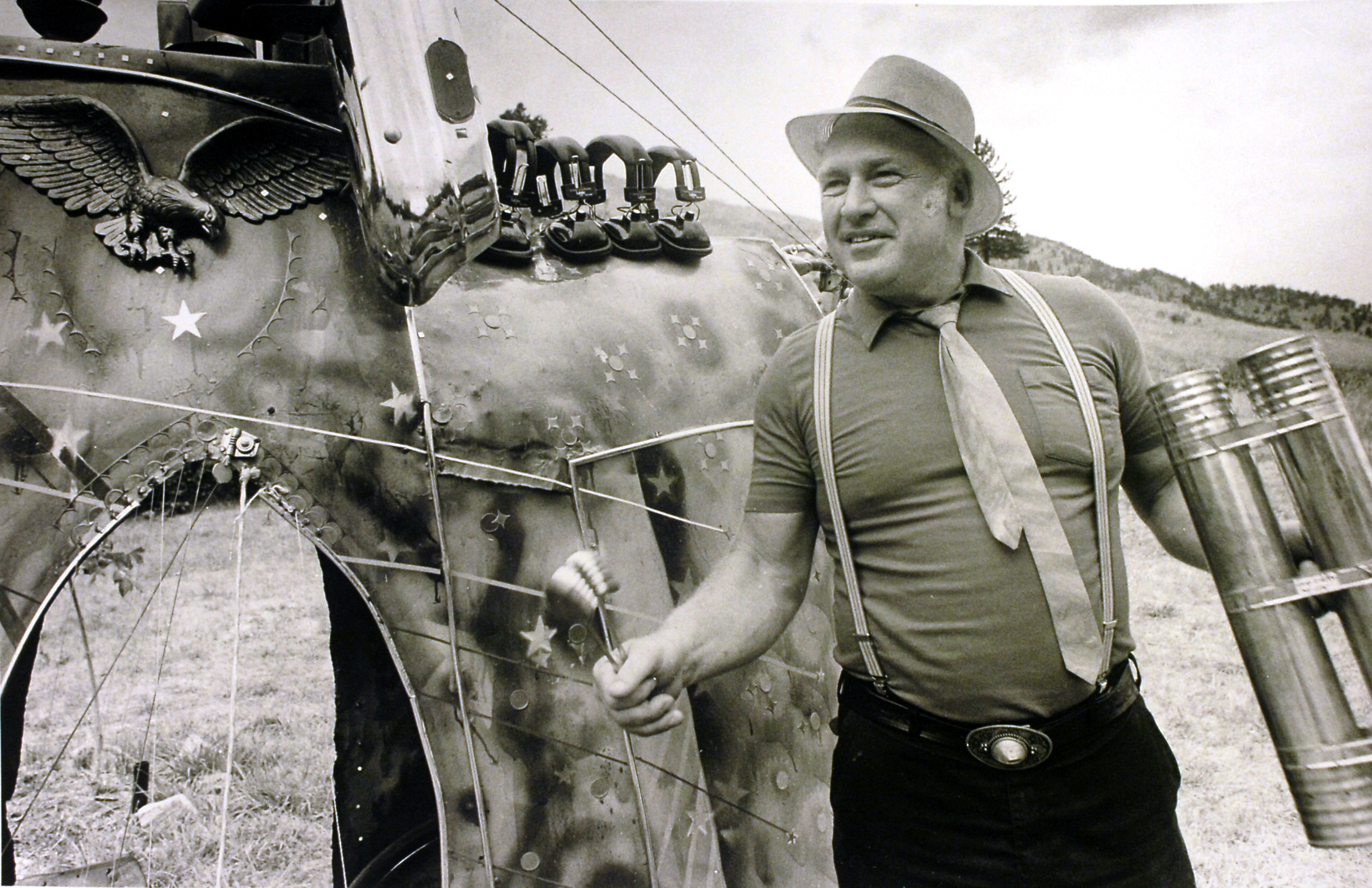

Novelist Ken Kesey—best known for the 1962 book One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest—hailed from a westward-trending family of "itchy-footed" wanderers, as he once put it. His parents settled for a time in La Junta, Colorado, where he was born in 1935. He lived there for the first eight years of his childhood. Kesey is shown here in Oregon, where he lived for most of his life. Photo by John Swan.

Kesey lived and did much of his later writing in Oregon, at the eighty-acre dairy farm in Pleasant Hill that once belonged to his paternal grandparents, and where he had spent much of his youth. He moved to the farm to raise a family following the success of his first two novels, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1962 and Sometimes a Great Notion in 1964, the latter an epic tale of strikebreaking Oregon loggers. He lived on the farm until his death at age 66 on November 10, 2001, following liver surgery.

Kesey’s lifetime output included novels, shorter writings, wildly illustrated journals and reminiscences, and two children’s books, plus scattered gems of film, music, theater, and multimedia mayhem. Kesey set most of his fiction—including the 1992 novel Sailor Song, a futuristic tale of Alaska, and the 1994 Last Go Round, about a legendary 1911 rodeo in Pendleton, Oregon—within sprawling northwestern landscapes peopled by colorful, quirky, and memorable characters.

In the process Kesey rightfully earned a lifetime association with the state of Oregon. But what comes as a surprise to many is that he was born in La Junta, Colorado, and spent the first eight years of his life there.

La Junta is a high-plains southeastern Colorado town in a land of sagebrush and piñon and vast expanses and strong winds. It was here, along the Santa Fe Trail, that Bent’s Fort was built in 1833 on the banks of the Arkansas River. The fort was a critical supply outpost and bartering locale for mountain men, traders, the region’s Plains Indians, and the military. La Junta remained an important crossroads in years hence, serving as a stage stop and then as a rail junction, a role it still has today.

Downtown La Junta, Colorado. The films on the theater marquee date this photo to 1943, the year the Keseys moved away.

Early homesteaders plowed the dry, rocky ground and ranched in this arid region with mixed success; but plowing and overgrazing led to the destruction of native grasses, and attempts to irrigate met with failure. So in the 1930s La Junta sat squarely within Dust Bowl country. And it was here that Ken Elton Kesey was born on September 17, 1935, to dairy farmers Fred A. and Geneva Smith Kesey.

Even devoted readers of Ken Kesey’s work are surprised to learn that he hailed from Colorado. It doesn’t help that journalists, critics, and sometimes the bios in Kesey’s own books claim that he was born and raised in Oregon. “Oh, I’ve read that many times,” says his mother, Geneva, who remarried after husband Fred Kesey’s death and became Geneva Jolley; she still lives in Oregon. (Editor's note: Geneva Kesey Jolley passed away at the age of 101 in 2017, nine years after the original publication of this essay.) Referring to the ramshackle house on the banks of a fictional Oregon river in Kesey’s second novel, she says, “The house that he wrote about in Sometimes a Great Notion...a number of people have argued with me that he was born there....It’s a misconception for people yet.” That house, she says, is “still on the Siuslaw River, near the coast, near Florence, just sort of dilapidated and falling down.” But the Keseys never lived in that house.

Ken Kesey has for so long been associated with his adopted state of Oregon that even the bios in a few of his books will tell you he was born there. "I've heard that one too," says his mother.

The 1977 Penguin paperback edition of Kesey's novel Sometimes a Great Notion, shown here, gets it wrong. Kesey was born in La Junta, Colorado, on September 17, 1935.

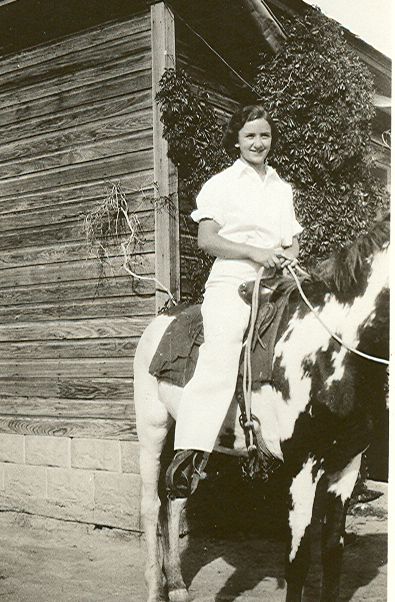

“It was happenstance that my family and I ended up in Colorado,” says Jolley. “We were young, and adventuresome.” Asked how this young girl from Fort Smith, Arkansas, met the slightly older Fred Kesey from Mobitee, Texas, she recalls simply, “We just bumped into each other.” The two ended up marrying in Florence, Colorado, and moved to La Junta in 1931. They bought a little house on Lewis Avenue. Ken’s brother, Joe, who later earned the nickname “Chuck,” was born three years after Ken.

Geneva and Fred were devout southern Baptists. Reading and storytelling were things of daily life: the Bible, the Tarzan tales of Edgar Rice Burroughs, and pulp westerns. Zane Grey was a favorite of Fred’s, and he read Grey’s western romances aloud to the family. Ken loved comic books, although whether he had yet acquired a taste for them (or could find them) in Depression-era Colorado may be anyone’s guess. An outdoorsman as well as a storyteller, Fred taught his sons from early on to love camping, fishing, and hunting. The family always had a dog, Geneva says. More than anything, her son Ken “could always take his dog and head out, up over the hill, and wander.”

Geneva’s parents came with them to La Junta, and Geneva’s mother became a lifelong influence on Ken Kesey. The boy spent hours listening to his grandmother telling tales and reciting rhymes. They called her “Grandma Smith,” and she was an inveterate storyteller in the tradition of the Ozarks, where she was born and where she raised Kesey’s mother. And although Ken Kesey himself never lived in the South, an Ozark-tinged cadence inflects much of his writing. A childhood memory of his grandmother gave Kesey the title of his first novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “It’s a nursery rhyme my mother had taught him when he was a little bitty boy: One flew east, one flew west, one flew over the cuckoo’s nest,” Jolley relates. “His Grandma Smith taught him that. And he had a high regard for his Grandma Smith.” During some of his many stage performances in later years, writes Kesey’s editor David Stanford, Kesey would put a scarf on his head and “evoke Gramma Smith and the storytelling that had inspired him, calling up an audience member to help him recite the nursery rhyme that gave Cuckoo’s Nest its name.”

Kesey dedicated his children's book Little Tricker the Squirrel Meets Big Double the Bear to his Grandma Smith, who told him that bedtime tale and many others during his childhood in Colorado.

Kesey’s grandmother lived until just a few days short of age 103. She and the stories she told him in Colorado and later in Oregon became the basis for a series of “Grandma Whittier” anecdotes he wrote. In 1990 he published the children’s book Little Tricker the Squirrel Meets Big Double the Bear, based on an Ozark story his grandmother had told him often. He dedicated the book to her: “For Grandma Smith, still lighting the dark.”

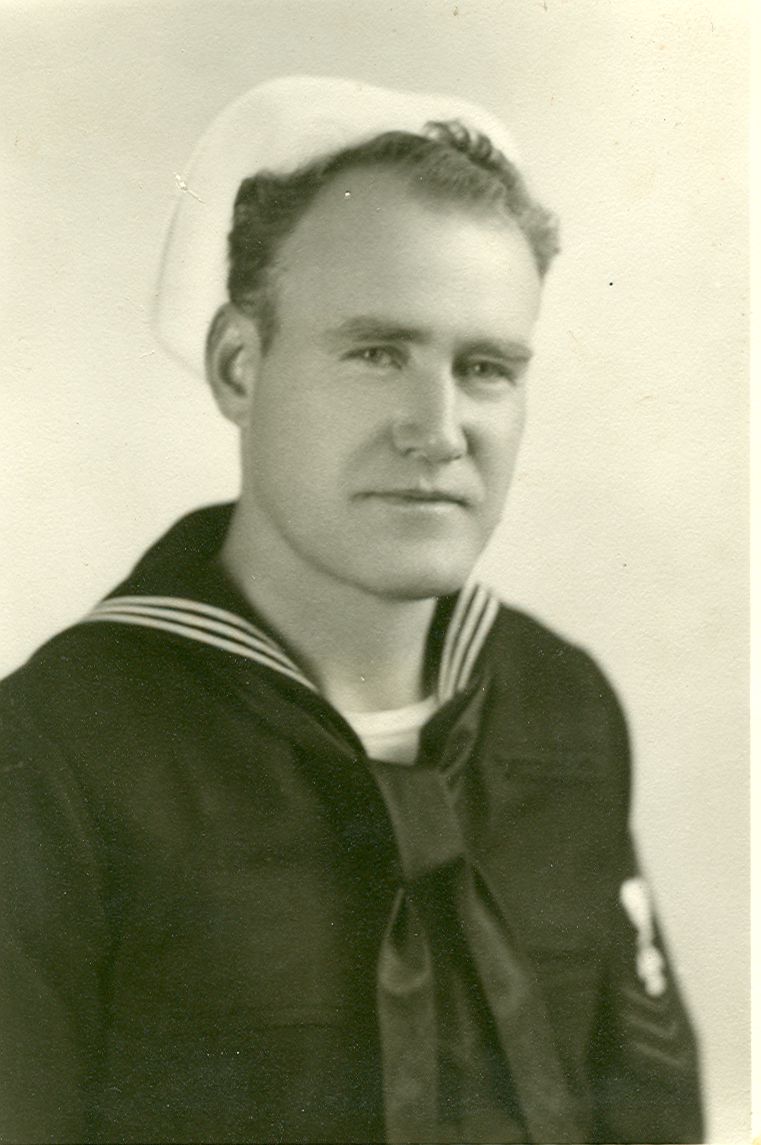

Ken Kesey’s father, Fred, wasn’t yet in the dairy business when he and Geneva arrived in La Junta. “Everybody was out of work, looking for a job,” Geneva says. Her husband found work at a Carlson Frink creamery in Denver. Then he and Geneva opened a little creamery of their own in Pueblo. “It was only probably a year and a half, two years at the most. Then the boys’ dad got over…patriotic, and enlisted in the Navy,” she says. Having been told that Fred would be called up in about three weeks, they sold the Pueblo creamery. Nine months later he finally got the call.

“We sold the business and he fiddled around...doing nothing,” Jolley says, “and he was not one to do nothing.” So they drove to Oregon to visit his parents at the farm outside Eugene. “He finally decided that his dad was working to death” on the farm, Jolley says, so Fred went to work at a Eugene creamery. He “didn’t tell them he had any background at all,” Jolley laughs. “He just went to work as a peon.”

When Fred got the call, he served at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California as a refrigerator mechanic (a skill he had learned in the creameries) and did a yearlong stint at sea. Geneva and the boys lived at nearby Boyes Hot Springs for the duration of his service. At war’s end, Fred rejected an offer from the Carlson Frink creamery back in Denver, and the family settled in Oregon for good. Geneva’s parents—Grandma and Grandpa Smith—joined them. Eventually Fred founded what would become one of the largest dairy cooperatives in Oregon. Ken’s brother, Chuck, continues to manage a major dairy business with his family in Oregon today.

As for their Depression-era household, the young Geneva Kesey kept busy raising her two boys. “I was not a working mother. I had a husband that resented working women,” she laughs. “He was the old-fashioned one.”

Did she see a budding writer in her oldest son? “He was always creative,” she recalls. “He was doing artwork. He was doing drama.” (Graphic arts and drama were subjects Kesey would later pursue in college before signing up with Wallace Stegner’s writing program as a graduate student at Stanford University, where he befriended fellow students such as Larry McMurtry, Robert Stone, and Wendell Berry and embarked on a writing career.) Even as a child, Kesey “was a pretty good artist,” Geneva Jolley says. “He did a lot of dabbling and doodling.” And, she adds emphatically, a lot of reading.

Ken Kesey, tallest, with his brother, Chuck, at far left, and their cousins Jimmy Kesey (with curly hair), Leonard Kesey (in front, with dark hair), and Dale Kesey.

Asked about La Junta itself, Jolley confesses that time has erased most of her memories of the town and her neighbors, although they had many friends there. What did make a lasting impression were the storms. “We had a number of dust storms in La Junta,” she says. “This was in the Dirty Thirties, of course. God, I hated it with a passion. I just…totally hated it. And you taped around the windows, you taped around the doors, and the dust still got in. You’d set the table for dinner in the evening, turn the plates upside down so the dust wouldn’t get in the plates. And it was miserable.”

The family did enjoy camping at Rye, a town several miles west of La Junta that still boasts a big public campground called Rye Mountain Park. “It was one of our favorite spots to go and camp. And one time we’d done this trip to Rye and coming home we hit a dust storm—it hit us—and we had a great big old fat Buick, and it just totally took the paint off the right side of that big old Buick.”

It sounds like a story straight out of a Ken Kesey novel.

“It had a way of being nasty,” Jolley says of the Dust Bowl, in a classic piece of understatement, and nearly as fierce were the hailstorms. “Had a hail storm one time. Easter time was the favorite time for hail storms it seemed. And the hail was big enough it broke windows in cars, dented the cars...they were like golf balls. So that’s pretty good sized stones to throw atcha.”

Still, Jolley says, when her husband announced that they were moving to Oregon, she couldn’t bear the thought of leaving Colorado. At first, she explains, “we just stayed in Colorado, because we were there.” But by 1943 the dust storms were over, and it was only with reluctance that she considered moving on. The family made its westward journey and, Jolley figures, “we got [Colorado] out of our system.”

Following Ken’s marriage to Faye Haxby in 1956, Jolley relates, “He and his wife drove back to Colorado, and they looked up the house we’d lived in. He said, ‘Gosh, Mom, it sure shrunk; I used to think it was a big house,’” she laughs. “They have a habit of doing that, don’t they?”

Even Kesey’s closest friends say he rarely mentioned his childhood there. Reflecting on the events of September 11, 2001, in a piece posted online just after his death, Kesey mentioned in passing an unforgettable instant from his days in La Junta. “I can remember Pearl Harbor,” he wrote. “I was only 6 but that morning is forever smashed into my memory like a bomb into a metal deck.”

Kesey wrote about his youth at length in just one published work, his son Zane recalls, and that was when he wrote about leaving Colorado. It was in an in-flight magazine for United Airlines, in March 1989. The magazine, VISàVIS, was the precursor to today’s Hemispheres. In a short piece titled “My Own Oregon Trail,” Kesey told of the day his father came home from the Navy and announced that the family was leaving La Junta. “In the war-hot summer of 1943 my father came home to Colorado on his first furlough from boot camp,” his remembrance begins.

He had lost weight and he had a white sailor’s cap pushed back on a skimpy crewcut. Past draft age, he had volunteered in spite of my mother’s objections. Didn’t he have two kids, for crying out loud? Yeah, but didn’t he also have two brothers in the Pacific, already fighting for freedom? He had enlisted and that was that.

We assumed he would spend the leave fixing our pump and patching the cistern, maybe a few days off for rabbit hunting up in the cedars. We assumed wrong. He pushed that hat forward over a sailor’s wink and announced in the cartoon voice of Popeye, “I has stood all of this dry old sticker patch I can stands! I can stands no more. We are moving to Oregon.”

He had it all planned out. While he would be off serving his hitch fighting the Axis, my mom and my brother and I were to stay with Grandma and Grandpa at their new farm. This itchy-footed old pair had pioneered the family’s way west a year before, seeking richer dirt and brighter horizons than our little town offered. Letters in my grandmother’s flowing script claimed they had indeed found their promised land, in a valley called the Willamette in a town called Coburg.

“Beautiful scenery all the way,” she wrote....

It was a drive of three days that seemed to stretch on forever. Jammed in the back seat with my brother, I sweated and fussed. I didn’t want to leave my hometown. I was about to start the third grade and I had friends there, special friends, and special places—tumbleweed forts and hideouts in the flinty rocks. Now it seemed everything was receding away in a snarl of engine smoke and dust.

And that scenery rolling endlessly past the car windows? Why, it wasn’t a bit beautiful! It was just as hot and sagebrushy as the sticker patch we’d left, was my view.

Though Kesey did produce that one remembrance of his Colorado childhood, it was into his fiction that he poured his most vivid memories of the region where he spent his first eight years. His second novel was the 1964 saga of a family of Oregon loggers that he titled Sometimes a Great Notion after a paraphrased line from the Leadbelly song “Good Night, Irene.” A character in that book is a woman named Viv Stamper, a “dust bowl girl” who before marrying into the Stamper family in Oregon was born and raised in Rocky Ford, Colorado—a town just a few miles from Kesey’s birthplace.

“Viv came from Colorado, from a hot, flat, swart town where scorpions hid in black cracks in the clay and tumbleweeds lined the fences to watch the cattle trucks roll by,” Kesey writes. “Rocky Ford was the town’s name, and, across a white wooden arch that supported a green wooden watermelon and spanned the incoming railroad, was lettered the town’s fame: ‘The Watermelon Capitol of the World.’”

Kesey accurately describes 1950s Rocky Ford as a “small Colorado truck-farming town,” where his main character, Hank Stamper, lands in jail. In the midst of the town’s annual watermelon fair, while a high-school brass band plays “The Stars and Stripes Forever” under the hot July sun, Stamper picks a fight after happening into town on his motorcycle. He ends up in the local lockup, overseen by Viv’s father and attended to by Viv.

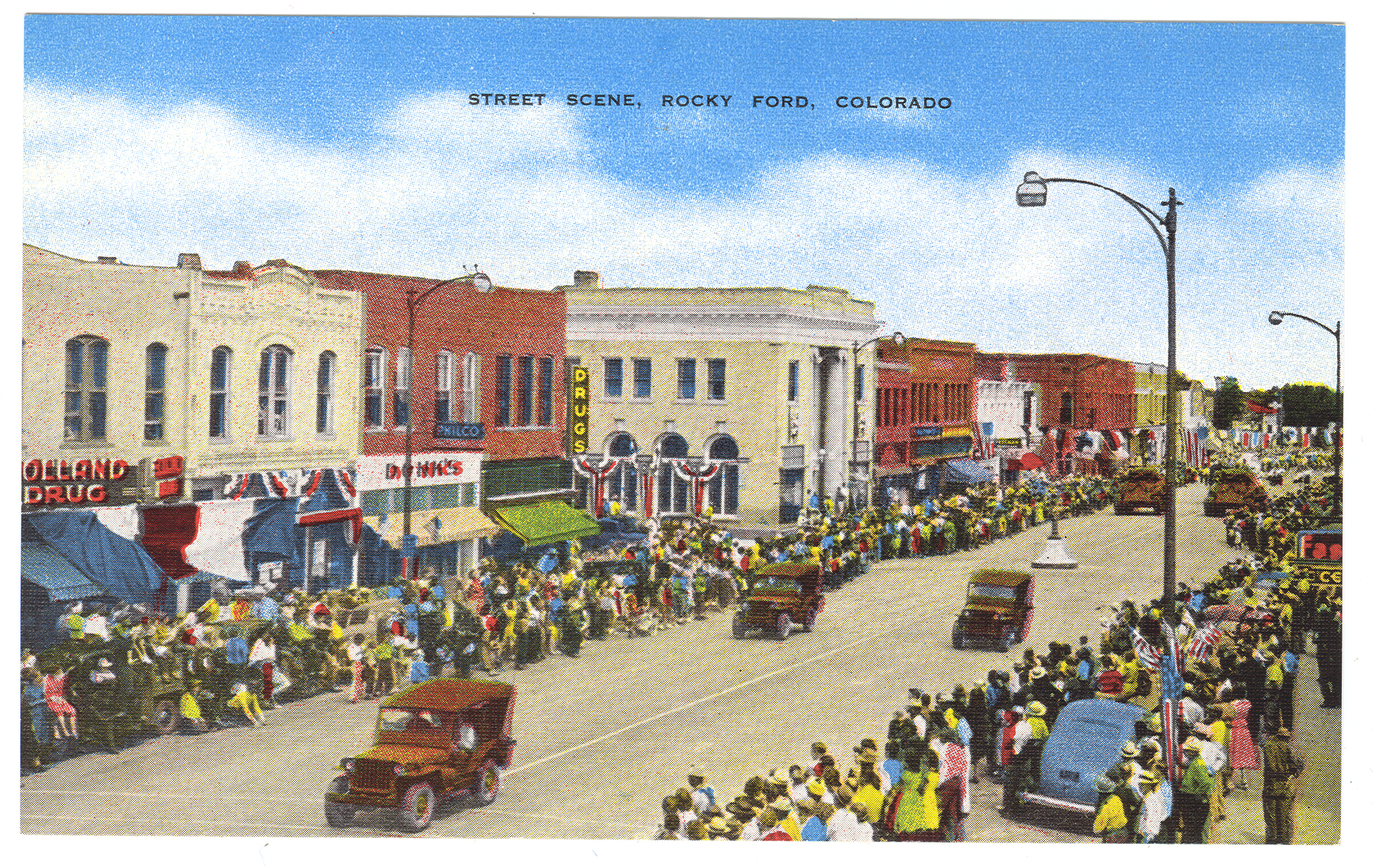

The scenario is an apt one. Founded in 1870 and named by frontier scout Kit Carson, Rocky Ford adopted the slogan “Melon Capitol of the World” in the late 1880s in honor of both its watermelons and its cantaloupes. The town’s melons, less plentiful today but still known for their size and sweetness, are feted every summer at a lively Watermelon Day celebration at the Arkansas Valley Fair. Over the years the festival has drawn boisterous crowds of young and old, local and out-of-towner.

Kesey obviously retained vivid impressions of Rocky Ford, whether from his childhood or from subsequent visits:

He drove slowly, down a main street bright with red and white striped bunting and rodeo posters....He liked the look of people milling about the sidewalks with bright satin ribbons pinned to their breast pockets, dangling little wooden melons. He liked cranky children, smeared with mustard, clutching long sticks to fat green balloons striped to look like watermelons; and hot women sitting shadowed in pick-ups fanning their cheeks with Watchtower pamphlets; and the melons stacked on gleaming straw in the backs of these pick-ups lettered across the tailgate with white shoe polish. FOUR BITS EACH THREE FOR A DOLLAR.

The characters of Hank and Viv later drive to the city of Pueblo for a movie, and Viv tells Hank of a time when her aunt took her to Mesa Verde to see the “Indian dwellings” and “Indian dances,” experiences Kesey may well have enjoyed as a child.

Another passage in the novel captures a memory that Kesey surely retrieved from his own childhood imagination, reflected in the character of Viv Stamper, who, like Kesey, has been uprooted from Colorado and transplanted to the Northwest Coast: “In the evenings she liked to look seaward and see that perfectly round sphere sinking to meet that perfectly straight line—so different from the jig-jag line of the Rockies that her childhood sun had turned into a row of volcanoes....”

North Main Street in Rocky Ford, Colorado, with crowds watching a 1940s parade on Fair Day. Courtesy Steve Grinstead

Hank...geared the cycle down to avoid the crowd mingling through the streets in flowered shirts and billowing slacks, sullen straw hats and hazy blue bib overalls. He called to the first baked face that turned slowly in the direction of his cycle, “Hey, Dad, which way to the free melons?” The question had surprising effect. The baked face shattered in a pattern of cracks like a clay pond bed drying suddenly in the terrific sun. “Sure!” the mouth croaked. “Sure! I work myself rag-assed t’ give melons away t’ the first, t’ the first smelly hobo who comes—” Then, as the face had shattered, the voice crumbled, becoming a rusty outraged squeak like a well sucking dust. Hank drove on, leaving the man clutching at his swollen red neck.

“I’d probably do better,” he decided, “asking one of the townspeople, or the tourists...and leave the poor devils from the farms alone. They act a little salty about free produce.”

[Viv] spent her summer days hoeing irrigation trenches through the heat-weaving Colorado melon fields, with her hair prickling her neck and sticking to her face and hanging the way it was aimed to hang. Her nights she spent trying to keep it from hanging in the zipper of her sleeping bag where she lay near a flashlight and a four-ten single-shot guarding against the bands of young thieves that her uncle claimed were waiting to pillage his fields at night.

In a country where melons grow wild along every waterhole, her uncle believed every poor soul in his jail to be secretly guilty of stealing his watermelons. The only marauders Viv had ever had a chance to rout were the jackrabbits and the prairie dogs....

—From Sometimes a Great Notion, 1964

“If American literature ever had a favorite son, distilled from the native grain, it was Kesey,” Robert Stone wrote in 2007. “That he had been born poor, to a family of sodbusters, served only to complete the legend.”

And what did Ken Kesey bring away from his childhood years in Colorado? Besides those occasional but vivid fictional pastiches he conjured of its towns, its landscape, and its people, a hint of an answer may be found in an interview conducted by Robert Faggen for The Paris Review in spring 1994. To mark the publication of Sometimes a Great Notion thirty years earlier, Kesey and a loose band of friends, family, and literary cohorts—who celebrated the possibilities of then-legal psychedelic drugs and were dubbed the “Merry Pranksters”—had embarked on a raucous coast-to-coast trip in an old International Harvester school bus painted in swirling Day-Glo colors. They wreaked good-natured chaos all along the way, and filmed and recorded and wrote it all down. Years later, when Faggen asked him what he had hoped to explore by embarking on that cross-country bus trip, Kesey responded, “What I explore in all my work: wilderness.”

As he put it, “Settlers on this continent from the beginning have been seeking wilderness and its wildness....Throughout the work of James Fenimore Cooper there is what I call the American terror. It’s very important to our literature, and it’s important to who we are: the terror of the Hurons out there, the terror of the bear, the avalanche, the tornado—whatever may be over the next horizon.”

Though Kesey credits his studies of early American writers for inspiring in him that fascination with whatever may be over the next horizon, one can’t help but wonder if the sense of wilderness so deep in his bones might not have had its truest beginnings in his childhood explorations of high-plains Colorado.

For Further Reading

A collection of essays about Ken Kesey’s life and career appeared after his death in Spit in the Ocean #7: All About Kesey, edited by Ed McClanahan (New York: Penguin Books, 2003). Also valuable, and containing a brief chronology of Kesey’s life, is the Viking Critical Library edition One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest: Text and Criticism, edited by John C. Pratt (New York: The Viking Press, 1973). Robert Stone writes at length about Kesey in his book Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007). Kesey’s friends still maintain a website, www.intrepidtrips.com, “as a monument and library.”

For details of the origins of Rocky Ford and the town’s earliest Watermelon Days, see Mr. and Mrs. James R. Harvey, “Rocky Ford Melons,” The Colorado Magazine, January 1949. The Eugene Field poem “Intry-Mintry” appeared in Poems of Childhood: The Writings in Prose and Verse of Eugene Field, volume four of The Works of Eugene Field (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901).

The author thanks Geneva Jolley for taking the time to share her memories of La Junta and her son’s childhood, and Zane Kesey for his help in tracking down family photographs and his father’s published memoir of his own “Oregon Trail.”

Ken Kesey visited Boulder, Colorado, in August 1986, bringing with him the enormous musical contraption he called the "Thunder Machine."

More from The Colorado Magazine

Taking Colorado Day by Day In conversation with author Derek R. Everett

Traveling the Storied Byway of the San Luis Valley: Summer Adventures Along Los Caminos Antiguos

Pioneer, Indian, Cowboy, Rabbi: Jewish Summer Camping in Colorado Generations of Jewish Coloradans have spent summer days at Camp Shwayder and the J Bar Double C Ranch Camp. Colorado’s mountains have provided the ideal setting for distinctly western Jewish American experiences. Ariel Schnee examines this lesser-known side of Jewish identity in Colorado.