Story

Japanese Americans in Denver’s Five Points Neighborhood

A Story about Tortillas

the disCOurse features writers sharing their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. In this article, Courtney Ozaki shares her family’s journey to Denver’s historically Black Five Points neighborhood, where a multigenerational love of tortillas was born.

Born and raised in Colorado, I am a “San-Hansei”, or third-and-a-half generation Japanese American; my mother is third generation with grandparents born in Japan and parents born in California, and my father is second generation with parents who were both born in Japan. My parents were born and raised in Colorado with both sides of my family finding a place of belonging in Denver’s Five Points and Curtis Park neighborhoods following the closing of the incarceration camps following the bombing of Hiroshima and the end of World War II.

Due to the signing of Executive Order 9066, which ordered 120,000 people of Japanese descent from the West Coast into incarceration camps with no legal cause, the families of my grandparents on my mom’s side, Mich and Rose Tanouye (with Rose at the time being a Tateishi) were forced alongside their families to leave all possessions and property behind, including their California farms, apart from what they were able to pack in one suitcase each. They were tagged like cattle with numbers and did not know where they were headed; their only crime being that they were of Japanese descent. Both of my maternal grandparents were American citizens.

The families were transported first to a race track where they had to degradingly clean out horse stalls so they might sleep in them temporarily, and were then sent to an incarceration camp which was built for them to ‘relocate’ to in Poston, Arizona. My grandma and grandpa Tanouye were introduced in the Poston Camp and eventually reconnected in Denver where they were married and settled down at 1026 29th Street, in a house which remains standing today but is now a lovely shade of bright blue.

After long years of war and life in the camps, Colorado, and more specifically Denver, was one of the ideal places to turn to in order to start anew amidst postwar racism, and many families ended-up rebuilding here. When my mom was born, and her sister, my aunt Maureen, was seven years old, the family moved to a small but slightly larger two bedroom house in north Denver. Grandpa Tanouye built a career doing upholstery work, and my grandma applied for a seamstress job at a western wear manufacturer. In order to be hired, she told a white lie that she had previous experience operating a power sewing machine. Despite not knowing what she was doing, she carefully observed and copied others who were doing the same job and she caught on quickly. She ended up working for that company for over 40 years, eventually working her way up to an administrative position in the office.

My grandma and grandpa, Tamiye and “Joe” Motoichi Ozaki, my father’s parents, had a much different story. In 1931, my grandfather left Japan to live in Peru with his uncle to help build up his parquet flooring business. My grandpa found success doing this, and eventually my grandmother was sent to Peru as a bride, arranged by their families. She arrived after days travelling on a boat, to a husband who didn’t recognize her from her picture due to the effects of the long journey.

Eventually, my grandfather took over his uncle’s business, and he and my grandma gave birth to my uncle Francisco (who now goes by “Joe”). When Joe was two years old, and while my grandmother was eight months pregnant with another child, World War II broke out. With no warning, my grandfather was seized by the American government, with the consent of the Peruvian government, essentially “kidnapped” by the United States. The intent was for Latin American Japanese to be used as a pawn of war, traded with Japan in exchange for Americans stranded there after the attack on Pearl Harbor. My grandmother, pregnant and with my uncle in tow, was able to eventually find her way to be with my grandfather, who ended-up in an “Alien Detention Center” in Crystal City, Texas. Sadly, she lost the baby, Hatsuko, born and deceased on August 8, 1943—eerily the same birthdate as my father’s when he was born years later.

My grandparents and uncle were also now forcibly “illegal aliens” entering the country without visas or passports. Following the war, Peru and other Latin American countries refused to let most Japanese people return to their homes. In order to stay in the United States my family was able to get sponsored by a distant cousin of my grandfather, who resided in Denver. My grandfather eventually purchased his cousin’s husband’s grocery store, and was able to provide for his family despite all odds against him including only sparingly speaking English.

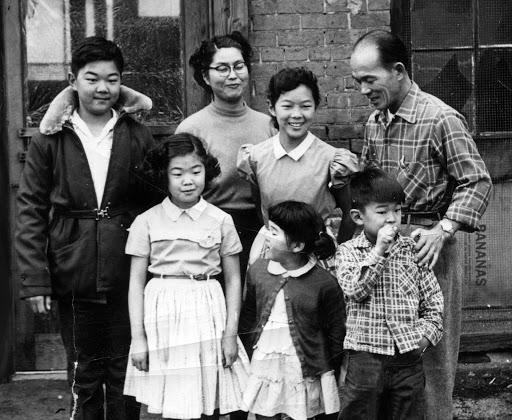

The Ozaki Family on Larimer Street. Top row: Joe, Tamiye, Martha, and Joe. Bottom row: Hiromi, Nancy, and Charles.

The title of this article is “A Story about Tortillas,” so what does all of this have to do with tortillas? The answer is in several stories of shared cultural joy. With both sides of my family landing initially in Five Points and Curtis Park neighborhoods, they were not only with other Japanese people but shared this space with communities that were predominantly Black and Latinx, mostly of Mexican descent, who had moved in there starting from the 1920s. Like those who came before them, the Japanese were not welcome to live where they wanted in Colorado, so many of them migrated to Curtis Park, which had long since become home to others who were not wanted elsewhere. The greater Five Points area, which included Curtis Park and Whittier, was considered undesirable real estate. As a result, housing costs were low and in many areas within the neighborhoods there were no restrictive covenants to keep anybody out. So those of modest means, or with no place else to go, could put a roof over their heads and settle down in this historically diverse, accepting place.

The fact that many people in the neighborhood spoke Spanish was helpful to my Ozaki grandparents for whom Spanish was more accessible than English after spending many years in Lima. In fact, during incarceration, my grandfather helped run a Spanish and Japanese newspaper. When asked about living in Five Points, the first thing that my father recollects from childhood is the MG Cafe, a Mexican restaurant that to this day he says had the “best burrito and green chili in Denver”. The cafe was on the same block as his house, which stood between 27th and 28th Streets on Larimer, beside the grocery store my grandparents managed. He and my mother both reminisce about the matriarch of the family-owned restaurant, who would sit by the door and pick through the pinto beans by hand. And, they fondly remember the sign on display that said something like “Keep your little feets off the counter” or “off the chairs.” Throughout my life I have accompanied my parents to numerous Mexican restaurants as they are always in search of an elusive dupe for the MG Cafe burrito.

Another story that has stuck in my memory is one my father shared with me of him playing by himself in the alley at the end of the block on the corner of 28th and Lawrence. A nice Mexican lady called him over and asked if he would like a freshly made tortilla. In this day and age it would be frowned upon for a child to accept a gift like this from a stranger, but back then he eagerly accepted it. Throughout my childhood, my dad was always very picky and particular about his tortillas, and he would often feed me a soft and deliciously comforting warm tortilla with melted butter inside it for breakfast.

My mother is also particular about her tortillas and she claims that her first generation Japanese grandmother, who lived with her family after the war because my grandfather was the oldest son, made the very best tortillas she has ever eaten. Though she spoke little English, and no Spanish, her neighbor in north Denver, Mrs. Rodriguez, taught her how to make tortillas and she in turn made them regularly for my mom and the whole family. I love reflecting on this now and cherishing the realization that this small bit of cultural joy, despite the circumstances, brought our communities together and has been passed down through generations of cultural continuum.

The Ozaki family in Crystal City, Texas with Tsuru for solidarity. From left to right: Charles, Teri, Nancy, Shannon, Meg, Joe, Keiko, Courtney.

There are many more stories about my family’s life beyond World War II: rebuilding in Denver and Colorado, being entrepreneurial, and working hard so that we, the future generations, would have the opportunity to be educated and pursue dreams of having a positive impact on the world. What was sacrificed by my family, and how they were able to rebuild in Denver despite being stripped of all of their rights and most of their worldly possessions, has had a significant impact on who I am today. My background and upbringing constantly provide me with strength, perspective, and resilience as I continue to forge my own entrepreneurial and sometimes overly ambitious path.

My grandparents on both sides of my family were resourceful and resilient, and I only ever knew them to be optimistic and generally cheerful. They didn’t always have a lot, but they still always were able to provide for their families. Any time I doubt my ability to keep moving forward, I remind myself that my entire family, only two generations back, had to gaman (or to “endure the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity”), and I observe how my parents established themselves in their respective professions. Recently retired, they have never stopped working hard to support me in my creative pursuits.

Not having been incarcerated, but surely being passed down generational trauma, while encountering racism and adversity on their own, my parents have taught me to not take anything in this life for granted, to always maintain deep gratitude, and to look forward to the future confidently, never doubting my ability, worth, rights, and value. My family history of surviving displacement, forced incarceration, and hardship has ingrained values that have encouraged me to pursue a meaningful life of helping others and encouraging artists to share their own stories of identity and cultural connection through artistic and creative platforms. I am proud to carry forward the integration and intersectionality of Japanese culture with other cultural communities through collaborative efforts between community organizations and the Japanese Arts Network, and I am grateful to History Colorado for highlighting the stories of how Denver’s Five Points was built by many incredible individuals within our communities of color.

Courtney and the Japanese Arts Network will lead a History Colorado walking tour of the Historic Japanese American Nihonmachi (Japantown) Neighborhood on August 28th, 2021 in Denver’s Five Points Neighborhood.

More from The Colorado Magazine

One Flew West When Ken Kesey described fictional southeastern Colorado settings and characters in one of his novels, he could rely largely on his own memory.

A Pivotal—and Long Overdue—Moment for Change What happened in 2020 was not unprecedented. Rather, it was a stark reminder that racism and classism had for too long gone unresolved.

Imagining a Great City Mayor Federico Peña’s campaign vision to “Imagine a Great City'' catalyzed the development of Denver and its region from the 1980s onward. Against the backdrop of a boom-and-bust economy, major public projects shaped the trajectory of the city along with its residents’ grassroots advocacy.