Story

11 things you didn’t know about Colorado’s path to statehood

Every August 1, we celebrate the day President Ulysses S. Grant made Colorado a state in 1876.

As we look back on this day in history, we don’t want to lose sight of what a journey it was and how that journey fits into the larger story of our nation.

Here are some fun facts you may not know about how Colorado became a state.

1. Jefferson Territory, which would later become the State of Colorado, was established at the same time as Denver City. Initially proposed names for the territory included Colona, Osage, and Idaho.

2. Laws for the territory were created in 1859—enforcing them was another matter. When a poll tax of one dollar was levied, 600 miners signed a pledge to resist. As The Colorado Magazine author LeRoy R. Hafen put it, they “promised the collectors bullets instead of dollars.”

3. In the 1860s there was a rivalry between the “Denver Ring” and the “Golden Gang,” both of whom wanted to be not only the capital of the territory but the centerpoint for railroad construction.

4. In the first attempt at statehood in 1864, proponents tried to keep costs low and set salaries at $1,000 for Secretary of State and $400 for Attorney General.

5. In 1865, conventions held to discuss statehood included the Republican and Democratic parties as well as a third party known as the Sand Creek Vindication party.

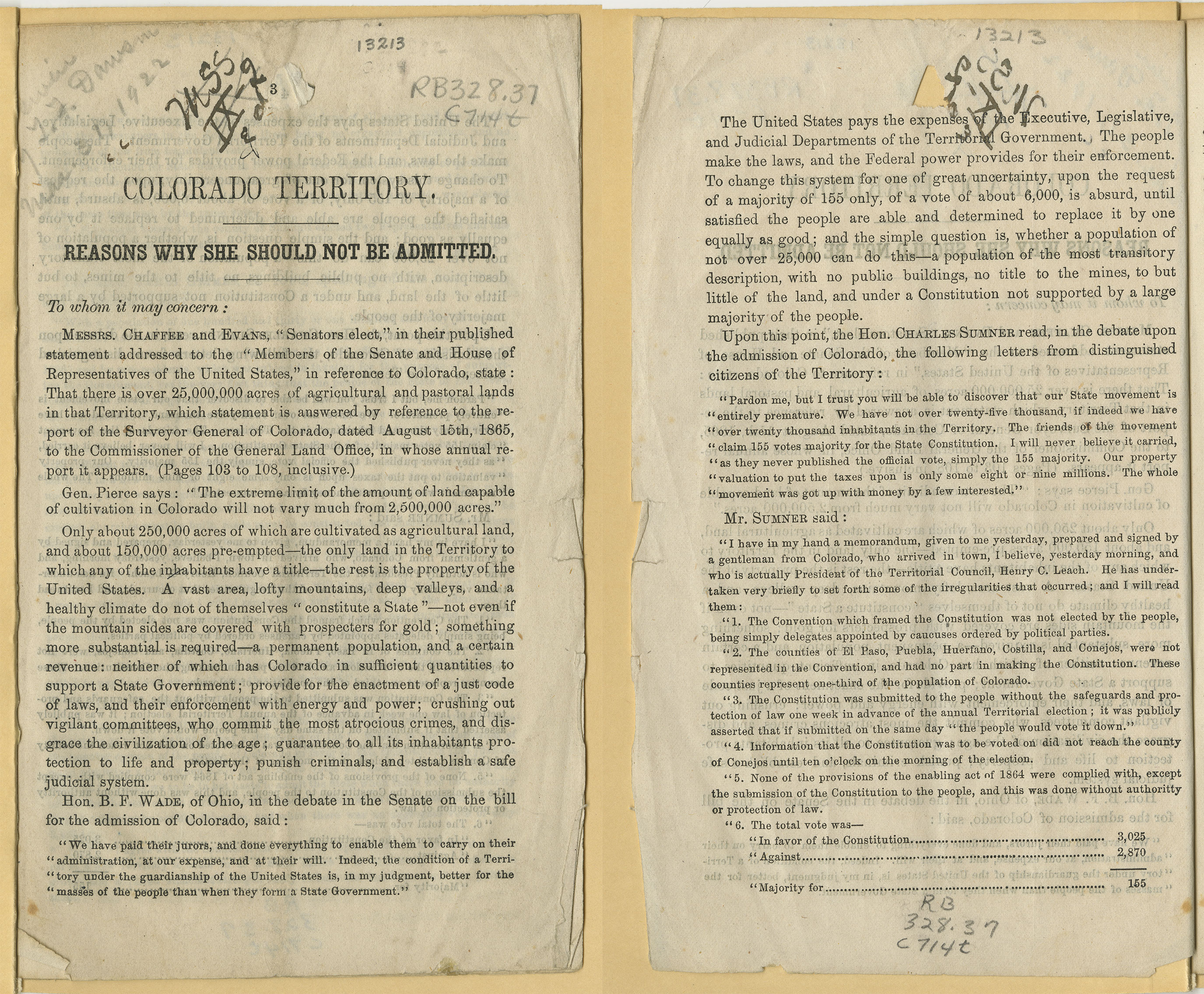

6. Population statistics were used to support arguments on both sides. At one point, advocates claimed there were 100,000 Coloradans while the opposition claimed there were only 30,000. Here are some official statistics from 1865, according to a couple pages of a document in our collection:

In this piece in our collection, several U.S. Congressmen discuss how population affects the ability to hold elections and to govern:

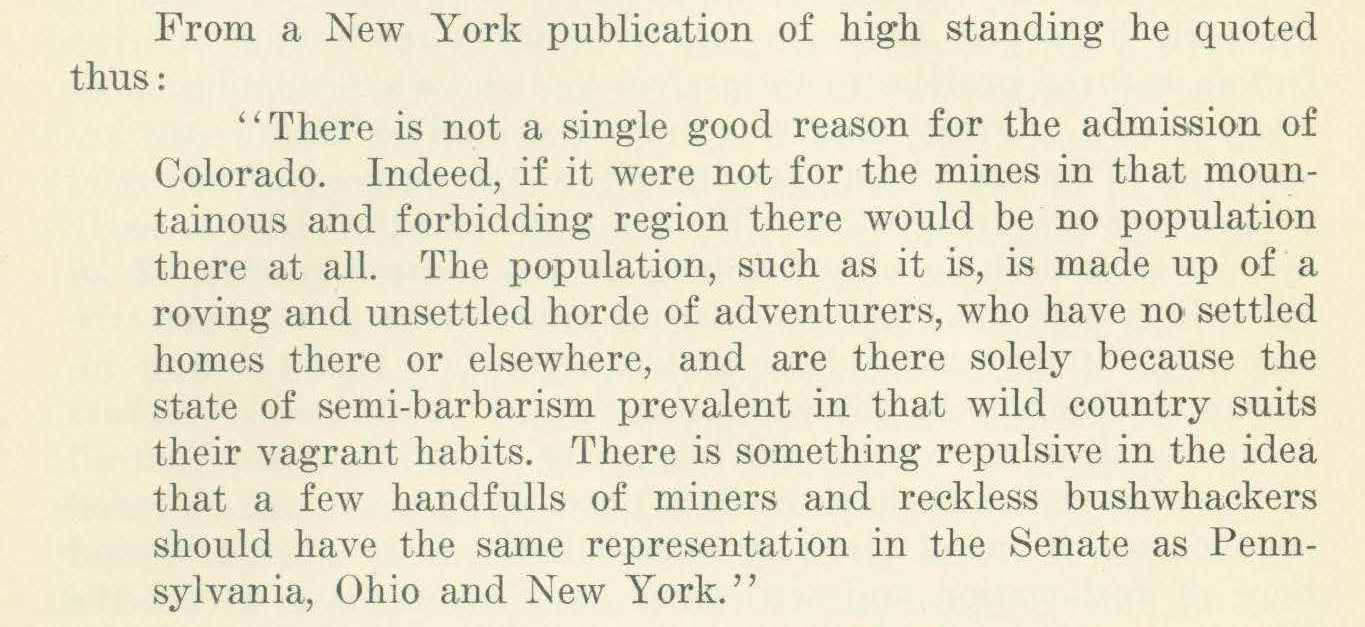

Beyond the numbers themselves, some viewed inhabitants (in particular miners) as “a roving and unsettled horde of adventurers, who have no settled homes there or elsewhere, and are there solely because the state of semi-barbarism prevalent in that wild country suits their vagrant habits.” Here is the full statement from a 1926 issue of The Colorado Magazine:

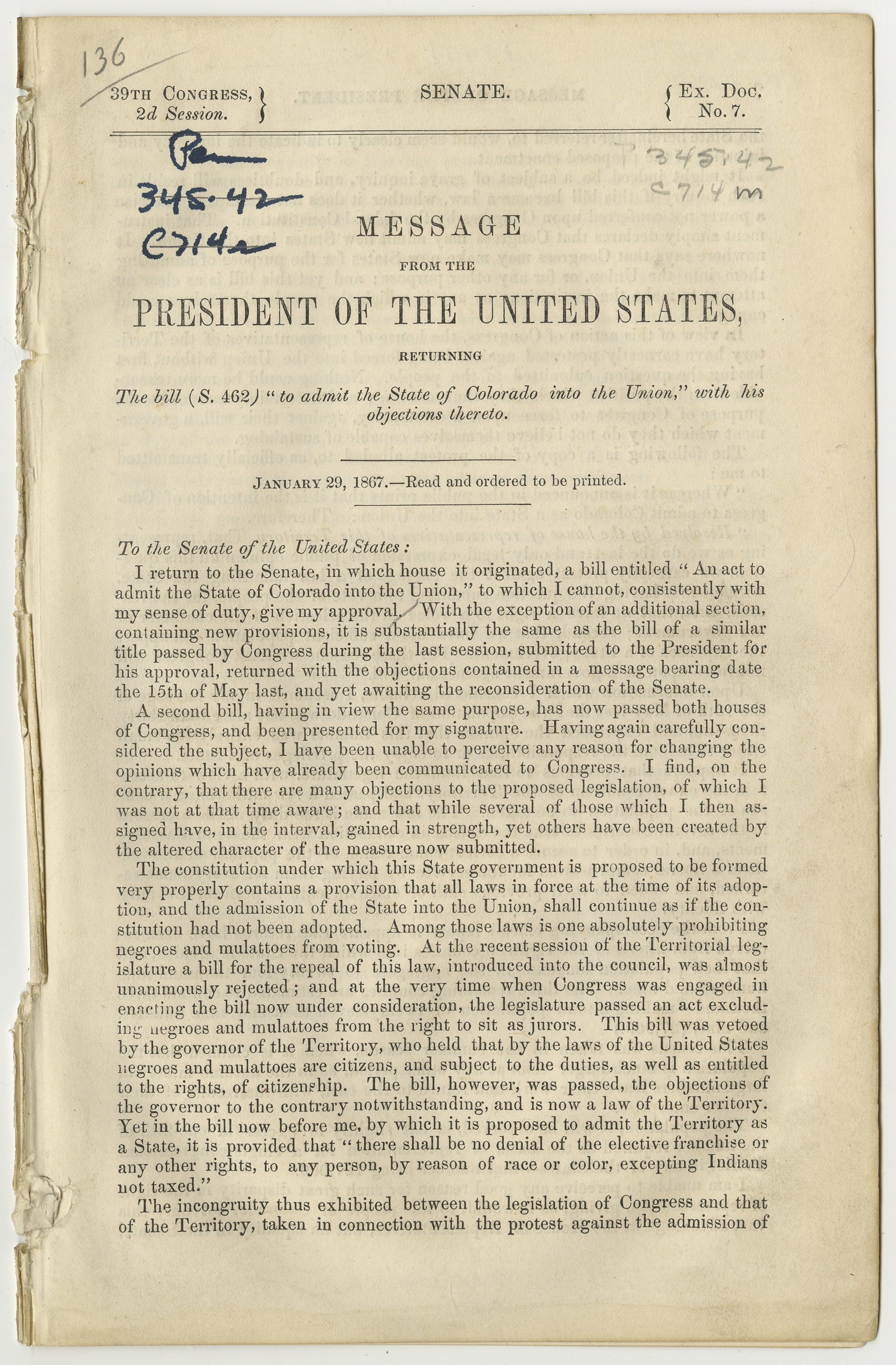

7. Suffrage for African Americans was a central issue throughout the process. In Colorado, it was overwhelmingly defeated, but when the bill went to Congress for a decision, some Easterners refused to pass it because of its exclusion. A later version ensured black suffrage. In this item in our collection, you can see how President Andrew Johnson addressed this issue when he rejected the bill in 1867.

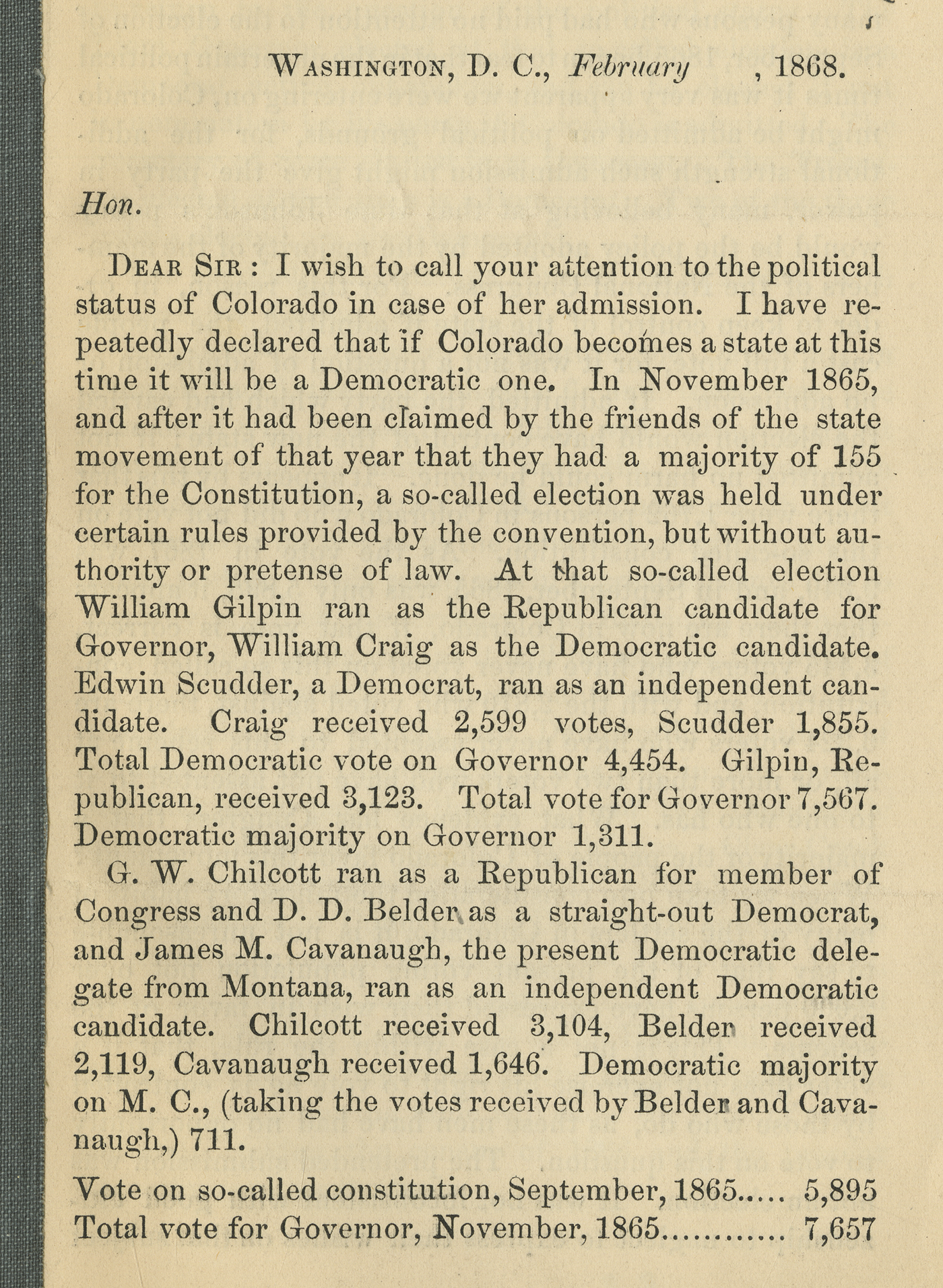

8. Party politics also played a big role. Henry Teller, leader of the Golden faction of the Republican party, opposed statehood in part because he thought it would mean more Democrats in office. After Colorado entered the Union, he was elected to the Senate, where, in a strange turn of events, he also served as a Democratic senator—even helping the Democratic Party gain more power in Colorado. A handful of items in our collection recount how in 1868 he made certain statements that others claimed to be false and then tried to defend them, including the letter started below.

9. It affected national politics immediately. Indeed, Thomas Patterson, Colorado’s first Democratic territorial delegate to Congress, persuaded fellow Democrats to support statehood by arguing that it would increase their numbers. Shortly after statehood passed, the 1876 presidential election took place—one of the most disputed in history. It was widely felt that Coloradan votes had made the difference. Since Republicans ended up taking the Oval Office, the Democrats who’d voted for statehood were disappointed and Patterson was blamed.

10. The initial statehood celebration on July 4, 1876, was also the 100th birthday of the United States (that’s why Colorado’s the “Centennial State”). In Denver, there were parades culminating in a stunning total of 13 toasts. In Canon City, they celebrated by beating South Pueblo in a game of baseball.

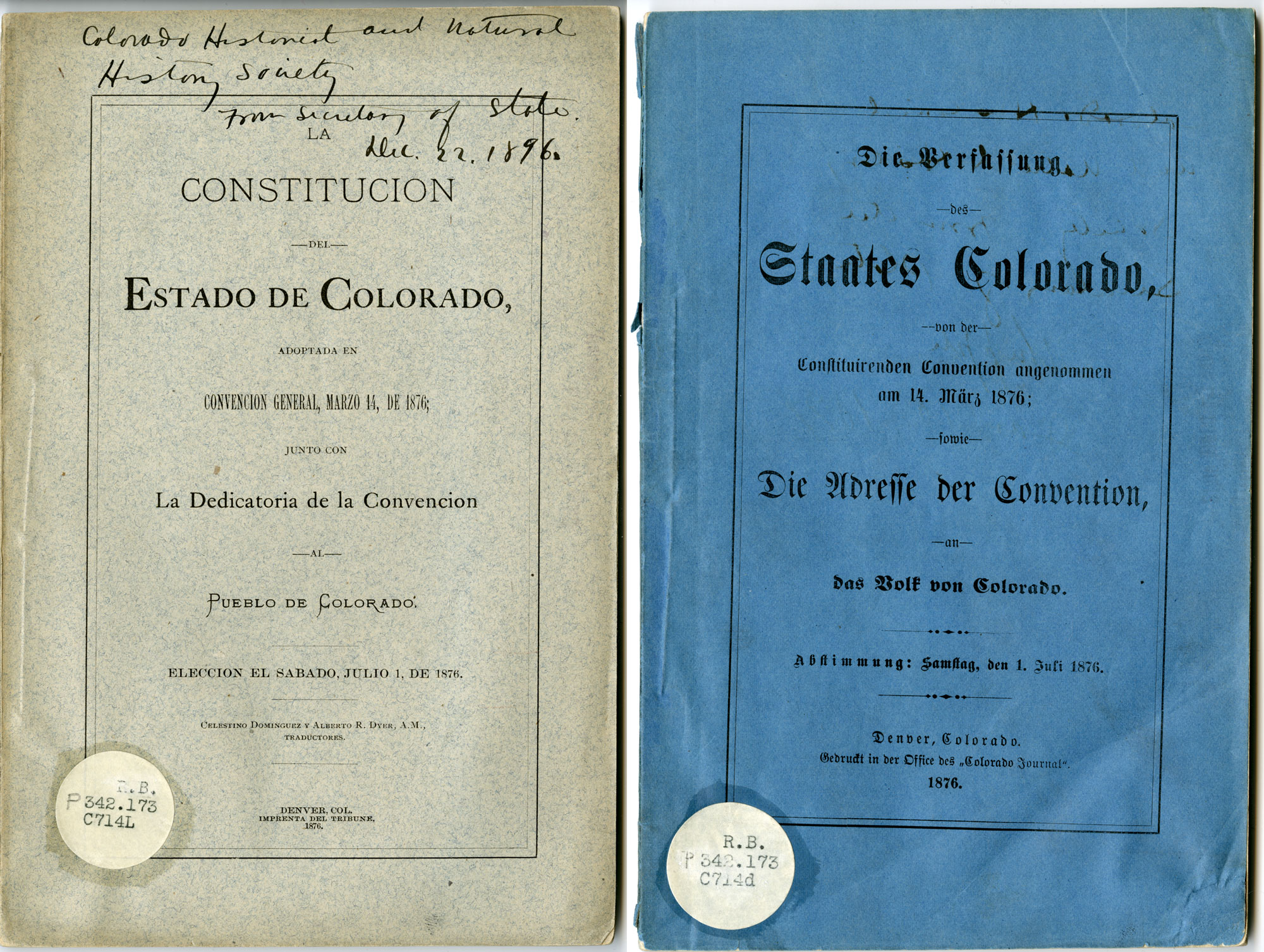

11. The Colorado Constitution was written in three languages: English, Spanish, and German. This was due to the efforts of Casimiro Barela, a territorial legislator who was born in then-Mexico. Be sure to visit our Zoom In exhibit at the History Colorado Center to see the Constitution and Spanish and German copies at El Pueblo History Museum.

If you want to find more interesting tidbits about Colorado’s statehood, or anything else related to Colorado history, you can check out Colorado Heritage and/or view the collection items in this blog as well as many others through our Hart Research Library.

Don't forget to come celebrate with us this August 1st! Not only will we have free admission to all of our museums, but each will have its own way of honoring the occasion.